Did the 19th amendment achieve voting rights for all?

Making Connections

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

In this activity you will analyze documents related to the women's suffrage movement and the journey towards "universal suffrage" – the right to vote for all adults. As you work, think about if and when this was ultimately achieved.In 1865, the 13th Amendment was ratified, formally abolishing slavery. Within the next three years, the 14th Amendment would also be added to the Constitution, granting citizenship to persons born or naturalized in the United States, which included newly freed slaves. Then with the 15th Amendment, African American men were granted the right to vote – a key component of citizenship in the United States.

But one half of the adult population – women – were still not guaranteed this right. Women's suffrage supporters had been organizing and pressuring Congress since the mid 1800s. The 19th Amendment, finally ratified in 1920, prohibited states from denying women the right to vote.

Follow the steps below. Read the questions and analyze the documents that follow — click "View Document Details" to learn more and see each one more closely. Answer the questions in the blank boxes that follow each document group. Then click "When You're Done," where you'll need to use what you learned from the documents to answer questions about the journey to universal suffrage.

Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

Did the 19th amendment achieve voting rights for all?

Making Connections

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Fill in any blanks in the sequence with your thoughts and write your conclusion response in the space provided.Just before the passage of the 15th amendment in 1869, the American Equal Rights Association met to discuss suffrage and the passing of the amendment. (Formed in 1866, the group's purpose was to “secure equal rights to all American citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color, or sex.") Differing opinions about only including black males in the 15th amendment created a schism in the Association, causing new associations to form for the cause of women’s suffrage specifically. The National Woman Suffrage Association formed as a women-only group, headed by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. While supporting women’s suffrage, this group opposed the ratification of the 15th amendment, because it would give black and immigrant men the right to vote in national elections, but omitted women (specifically educated white women whom they felt should certainly have the same rights as black and immigrant men). Nevertheless, the 15th amendment was ratified, giving newly freed black men the right to vote, and leaving out both black and white women.

Look at the primary sources below, then answer the following questions in the response box: What do these documents show about the push for women’s (universal) suffrage in the years leading up to the ratification of the 19th amendment? What do these documents display about race issues regarding universal suffrage?

Women Marching in Suffragette Parade, Washington, DC

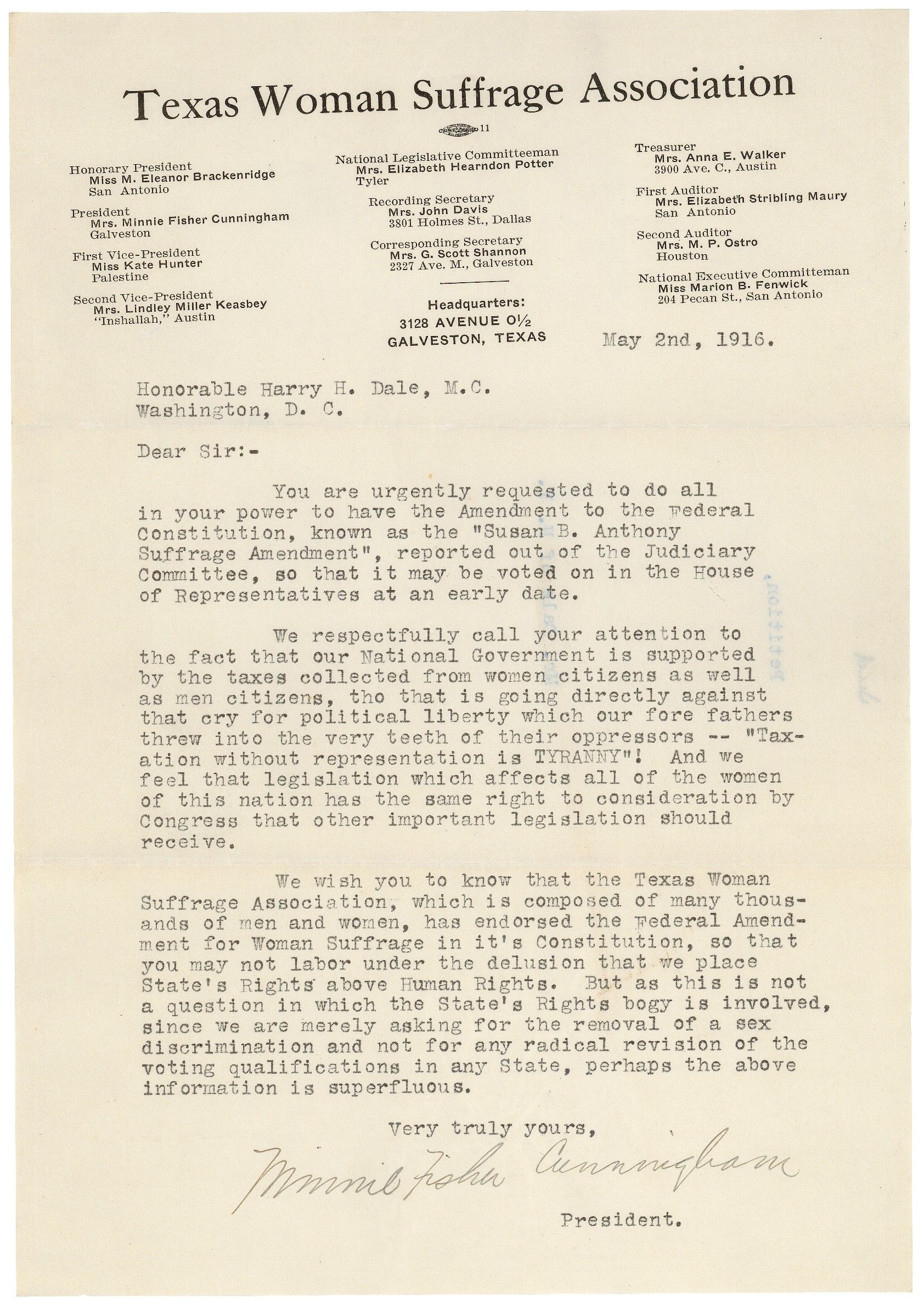

Petition from Minnie Fisher Cunningham of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association for passage of the "Susan B. Anthony Amendment"

Letter to Edwin Webb from Carrie Chapman Catt Comparing Negro Rights with the Rights of Southern White Women

Enter your response

The 19th amendment was ratified in 1920. It states that “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.” In 1920, women were able to vote for the first time in a presidential election. Analyze the following documents and answer: What do these documents demonstrate about who could now vote? Be sure to read any accompanying text under each document.

Act of June 2, 1924, Public Law 68-175, 43 STAT 253, which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians.

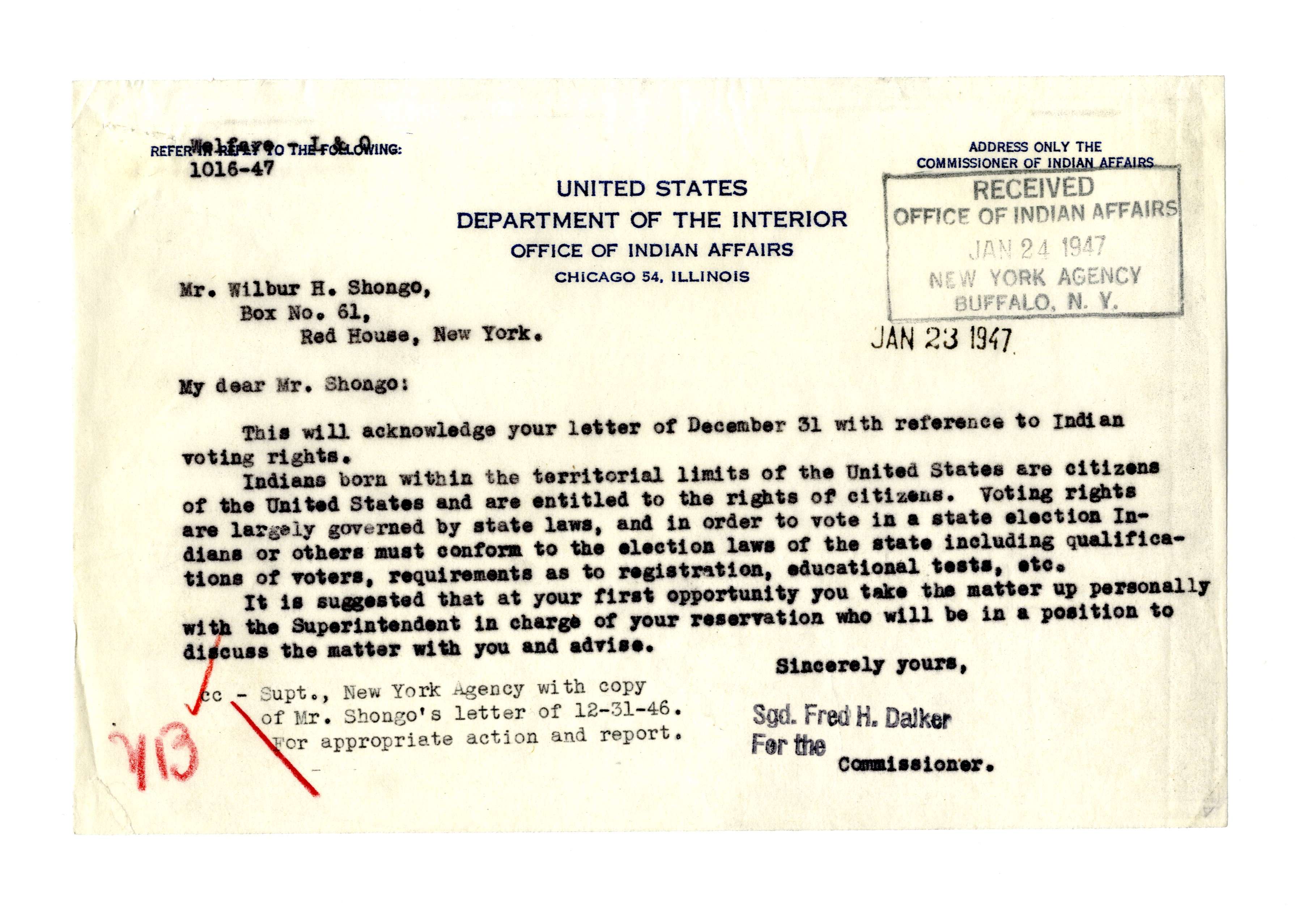

Letter to Wilbur H. Shongo from Fred H. Dalker about American Indian Voting Rights

San Bruno, California. Entering Recreational Hall where election is being held for Councilman...

Enter your response

Nearly 50 years after the ratification of the 19th amendment and nearly a century after the 15th, issues regarding voting rights persisted regarding minority groups. In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Acts of 1965, which outlawed discriminatory voting practices that were taking place, particularly in the South. These laws, also known as Jim Crow laws, often imposed poll taxes and literacy tests that aimed to disqualify African Americans from voting. What do you notice in this 1965 photograph? Who is present? Are there other groups of Americans who are not represented?

Photograph of President Lyndon Johnson Signs the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr., with Other Civil Rights Leaders in the Capitol Rotunda, Washington, DC

Enter your response

Look at the next two documents — compare the 1972 legal complaint document to the 1975 extension of the Voting Rights Act that was signed by President Ford. What problems persisted after the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act? Reflect on who was not present in the 1965 photograph from above.

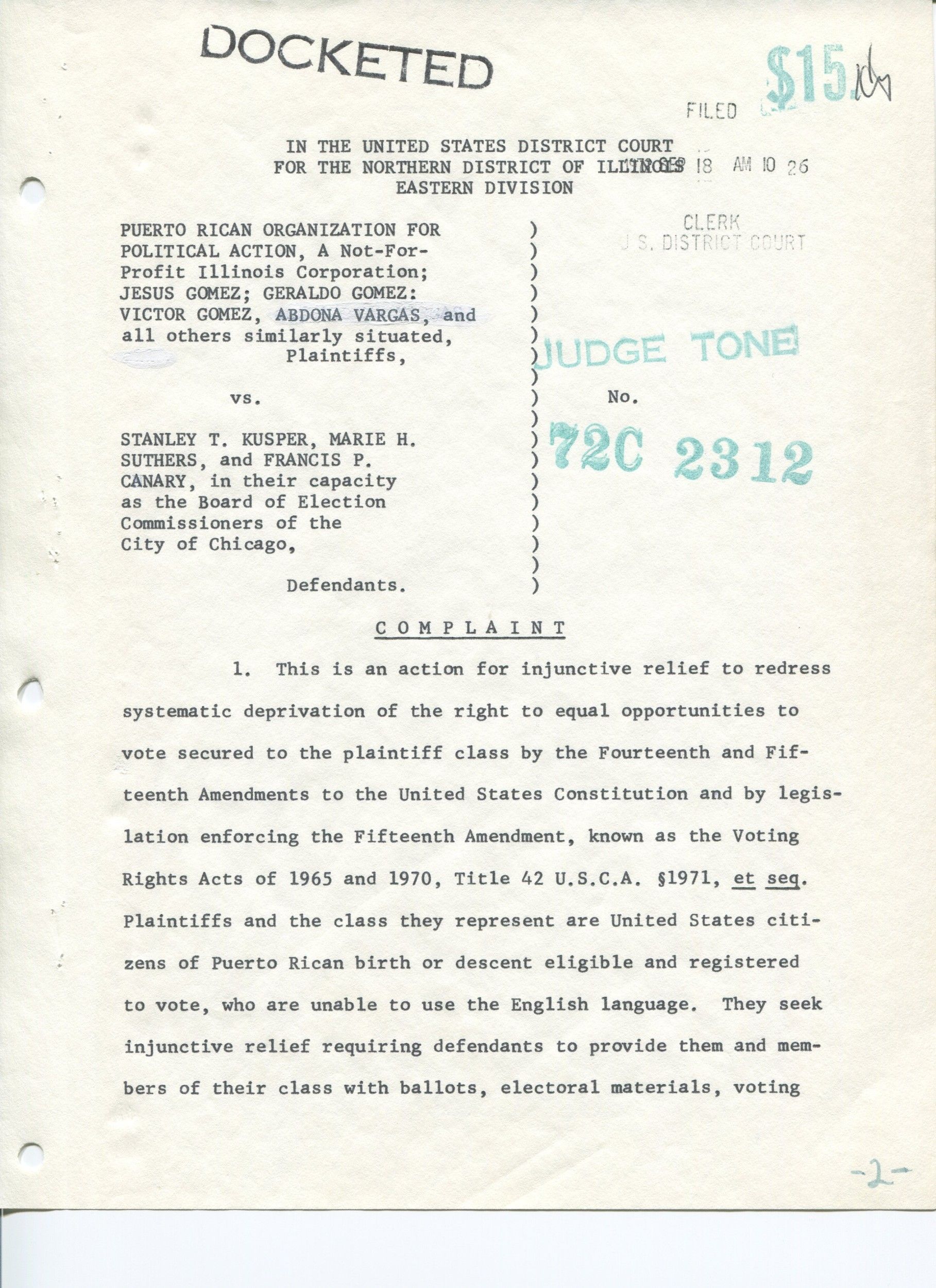

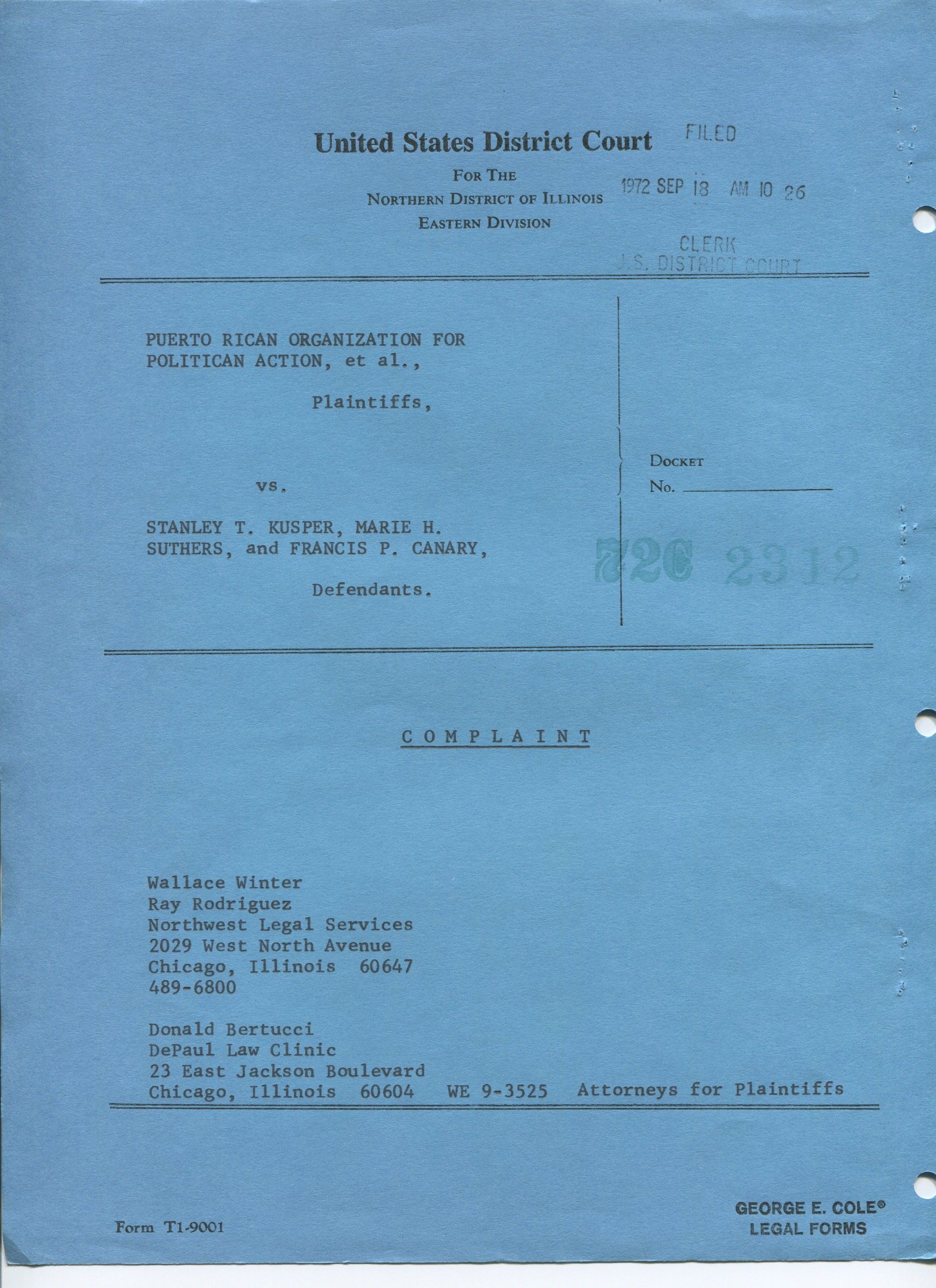

Complaint

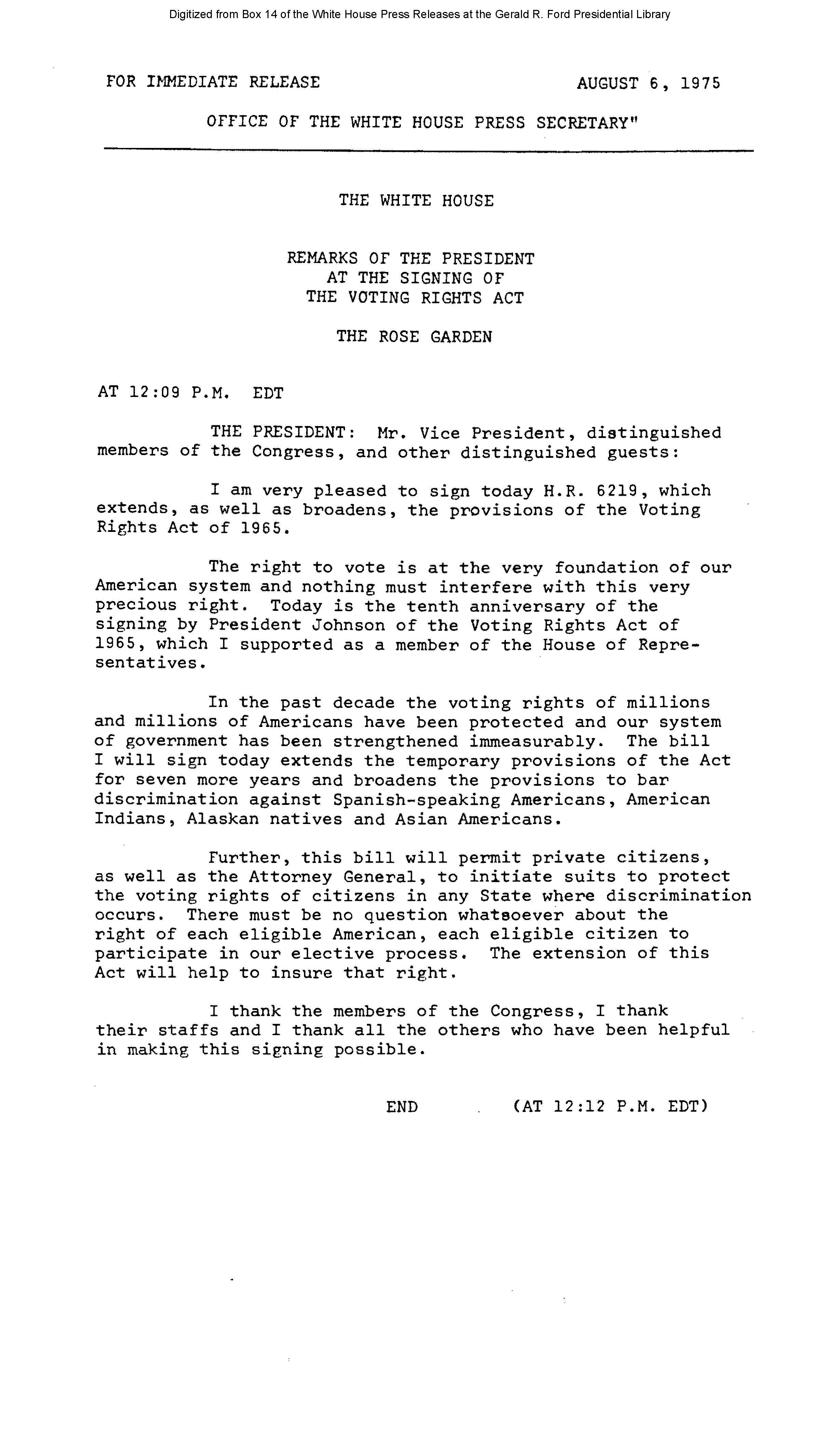

Remarks of the President at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act [Ford Speech or Statement]

Enter your response

1

Activity Element

Women Marching in Suffragette Parade, Washington, DC

Page 1

2

Activity Element

Petition from Minnie Fisher Cunningham of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association for passage of the "Susan B. Anthony Amendment"

Page 2

3

Activity Element

Letter to Edwin Webb from Carrie Chapman Catt Comparing Negro Rights with the Rights of Southern White Women

Page 1

4

Activity Element

Act of June 2, 1924, Public Law 68-175, 43 STAT 253, which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians.

Page 1

5

Activity Element

Letter to Wilbur H. Shongo from Fred H. Dalker about American Indian Voting Rights

Page 1

6

Activity Element

San Bruno, California. Entering Recreational Hall where election is being held for Councilman...

Page 1

7

Activity Element

Photograph of President Lyndon Johnson Signs the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr., with Other Civil Rights Leaders in the Capitol Rotunda, Washington, DC

Page 1

8

Activity Element

Complaint

Page 2

9

Activity Element

Remarks of the President at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act [Ford Speech or Statement]

Page 1

Conclusion

Did the 19th amendment achieve voting rights for all?

Making Connections

In the past 150 years, millions more Americans have secured their voting rights as laws changed and discriminatory practices designed to keep certain voters from the polls were eliminated. Long after the passage of both the 15th and 19th amendments, however, certain groups of Americans – especially those of color and the poor – were still fighting for their right to vote. Even to this day, the promise of these amendments is yet to be enjoyed by all Americans as election laws continue to change and many continue to face barriers to voting.Reflect on this collection of documents and answer:

- What social problems and divisions were present during the women's suffrage movement?

- According to these documents, what groups of Americans still struggled to obtain the right to vote even after the 19th amendment was ratified in 1920? These documents only highlighted some of these groups – can you think of others?

- Do any of these issues come up in current events today? Have you heard of issues surrounding voting rights for certain groups of Americans in the news?

Your Response

Document

Women Marching in Suffragette Parade, Washington, DC

3/3/1913

In the second decade of the 20th century, suffragists began staging large and dramatic parades to draw attention to their cause. One of the most consequential demonstrations was a march held in Washington, DC, on March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s first presidential inauguration. More than 5,000 suffragists from around the country paraded down Pennsylvania Avenue from the U.S. Capitol to the Treasury Building.

It set a precedent for future protest marches, but also brought controversy. According to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), all women and men were welcome to march. However, march organizer Alice Paul attempted to exclude black women from participating because she feared white women would not march alongside them. Ultimately NAWSA forced Paul to allow black women to join the procession. Some women of color – such as civil rights crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett and lawyer Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians – bucked the attempt to racially segregate the parade by walking alongside white women.

The rowdy, mostly-male crowd watching the parade pressed in on the demonstration, at times leaving barely enough room for the marchers to get by. Many women were verbally and physically assaulted while the police stood by either unwilling or unable to control the crowd. Outrage over the violence resulted in a Congressional investigation into the lack of police protection for the marchers and increased sympathy for woman suffrage.

It set a precedent for future protest marches, but also brought controversy. According to the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA), all women and men were welcome to march. However, march organizer Alice Paul attempted to exclude black women from participating because she feared white women would not march alongside them. Ultimately NAWSA forced Paul to allow black women to join the procession. Some women of color – such as civil rights crusader Ida B. Wells-Barnett and lawyer Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin, a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians – bucked the attempt to racially segregate the parade by walking alongside white women.

The rowdy, mostly-male crowd watching the parade pressed in on the demonstration, at times leaving barely enough room for the marchers to get by. Many women were verbally and physically assaulted while the police stood by either unwilling or unable to control the crowd. Outrage over the violence resulted in a Congressional investigation into the lack of police protection for the marchers and increased sympathy for woman suffrage.

Transcript

We demand an amendment to the Constitution of the United States enfranchising the women of this countryThis primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Information Agency.

National Archives Identifier: 24520426

Full Citation: Photograph 306-PS-57-7357; Women Marching in Suffragette Parade, Washington, DC; 3/3/1913; Master File Photographs of U.S. and Foreign Personalities, World Events, and American Economic, Social, and Cultural Life, ca. 1953 - ca. 1994; Records of the U.S. Information Agency, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/marching-suffrage-parade-dc, April 19, 2024]Women Marching in Suffragette Parade, Washington, DC

Page 1

Document

Petition from Minnie Fisher Cunningham of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association for passage of the 'Susan B. Anthony Amendment'

5/2/1916

Minnie Fisher Cunningham, president of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association, sent this petition in support of passage of the Susan B. Anthony Amendment, the name given to the 19th Amendment. In it she stated that "taxation without representation is tyranny!"

Cunningham also wrote "this is not a question in which the State’s Rights bogy is involved." She argued that woman suffrage would not threaten Southern states' rights because suffragists sought no other changes to voting qualifications besides the "removal of sex discrimination." In other words, Southern states' laws designed to prevent people of color from voting would not be threatened.

Cunningham also wrote "this is not a question in which the State’s Rights bogy is involved." She argued that woman suffrage would not threaten Southern states' rights because suffragists sought no other changes to voting qualifications besides the "removal of sex discrimination." In other words, Southern states' laws designed to prevent people of color from voting would not be threatened.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives.

National Archives Identifier: 306659

Full Citation: Petition from Minnie Fisher Cunningham of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association for passage of the 'Susan B. Anthony Amendment'; 5/2/1916; (HR64A-H13.6); Petitions and Memorials, 1813 - 1968; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/tx-woman-suffrage-petition, April 19, 2024]Petition from Minnie Fisher Cunningham of the Texas Woman Suffrage Association for passage of the 'Susan B. Anthony Amendment'

Page 2

Document

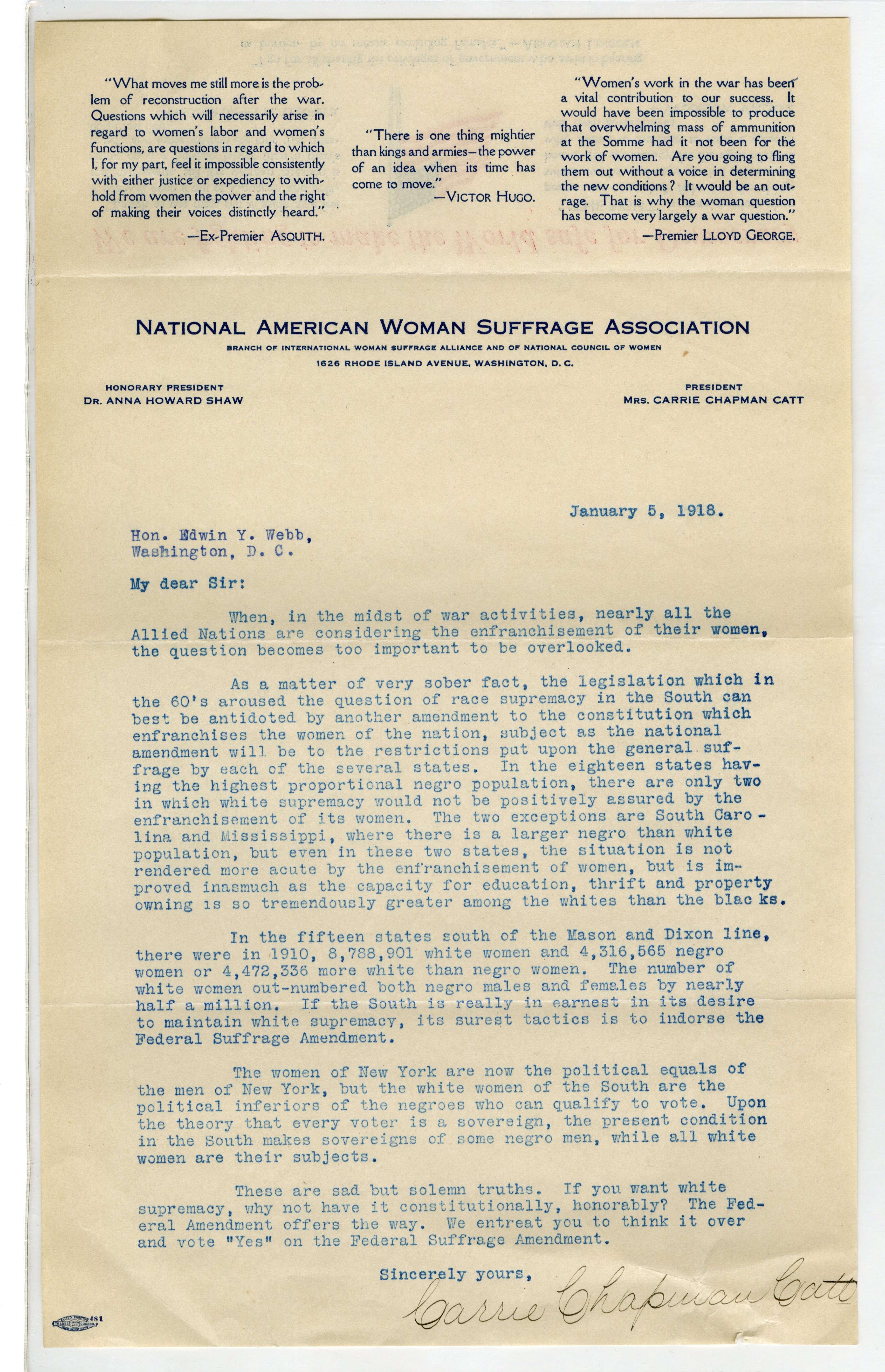

Letter to Edwin Webb from Carrie Chapman Catt Comparing Negro Rights with the Rights of Southern White Women

1/5/1918

Carrie Chapman Catt, who replaced Susan B. Anthony as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1900, sent this letter to Congressman Edwin Y. Webb of North Carolina. She suggested that granting white women the vote would neutralize the vote of the "negro population." She wrote: "If the South is really in earnest in its desire to maintain white supremacy, its surest tactics is to indorse [sic] the Federal Suffrage Amendment."

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2017 summer workshop in Washington, D.C.

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2017 summer workshop in Washington, D.C.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives.

National Archives Identifier: 74884353

Full Citation: Letter to Edwin Webb from Carrie Chapman Catt Comparing Negro Rights with the Rights of Southern White Women; 1/5/1918; Petitions and Memorials, Resolutions of State Legislatures, and Related Documents Which Were Referred to the Committee on the Judiciary during the 65th Congress; (HR65A-H8.14); Petitions and Memorials Referred to the Committee on the Judiciary, 6/3/1813 - 1998; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/webb-carrie-catt, April 19, 2024]Letter to Edwin Webb from Carrie Chapman Catt Comparing Negro Rights with the Rights of Southern White Women

Page 1

Letter to Edwin Webb from Carrie Chapman Catt Comparing Negro Rights with the Rights of Southern White Women

Page 2

Document

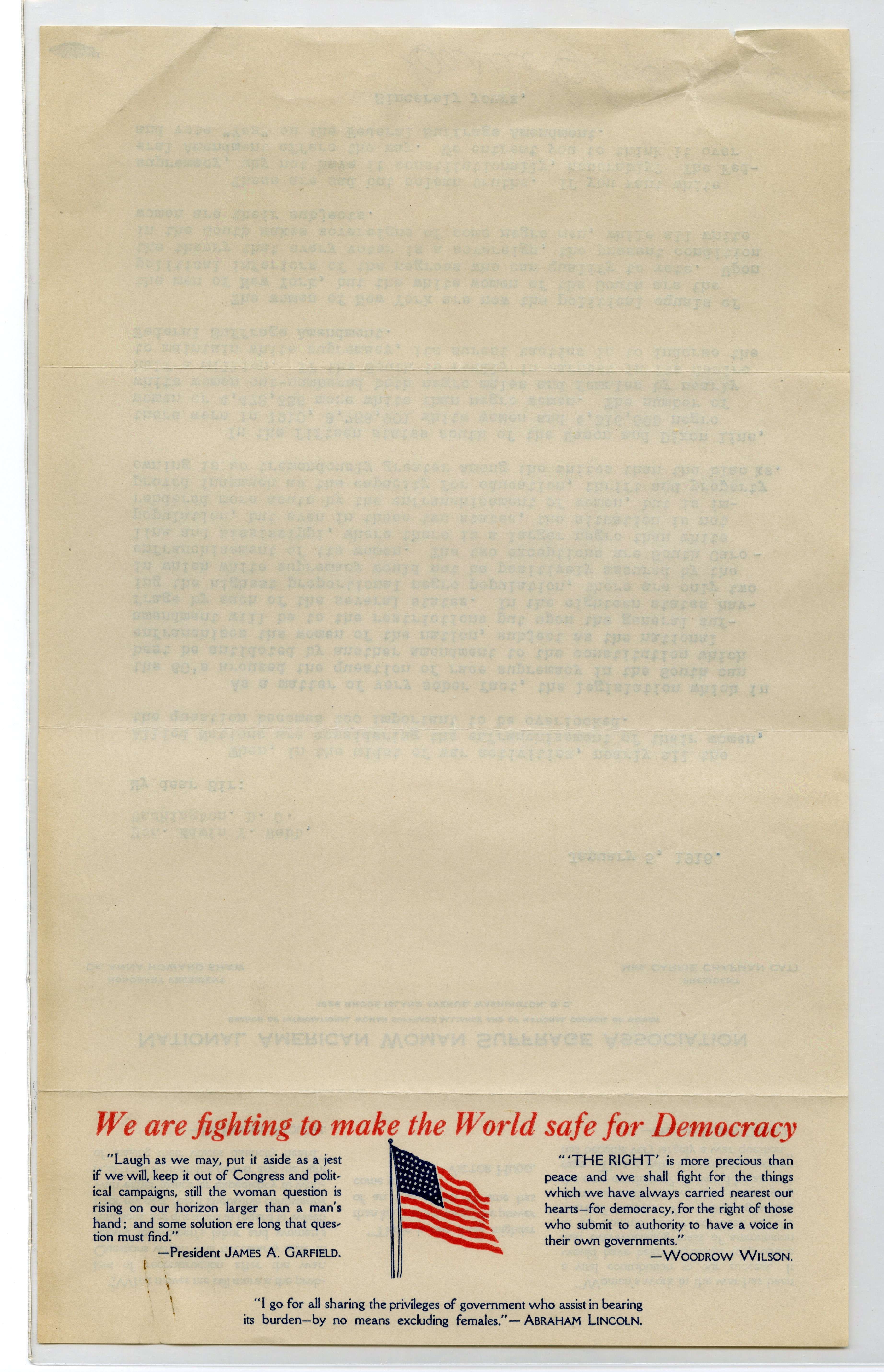

Act of June 2, 1924, Public Law 68-175, 43 STAT 253, which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians.

6/2/1924

The Indian Citizenship Act extended citizenship to the approximately 125,000 Native Americans who were still not recognized as American citizens in 1924. This act (Public Law 68-175, 43 STAT 253), also known as the Snyder Act, authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to American Indians.

After World War I, honorably discharged Native American veterans had been granted citizenship for their service. Not long afterwards, many urged naturalization for all of America’s indigenous peoples who were not yet recognized as American citizens. Determining that "it was only just and fair that all Indians be declared citizens," Congress passed the Indian Citizenship Act.

Although Native Americans were finally recognized as "citizens" of the United States in 1924, the overall impact on their rights was minimal. Under the act, Native Americans still retained their tribal affiliations and rights to tribal property. This part created confusion over Native American rights. It led future Government officials to believe that Native Americans were not full American citizens, and therefore not entitled to all of their rights.

Many tribes remained as wards of the Government, and the right to vote was slow to arrive for Native Americans in certain states. It would be decades before Native Americans were allowed to vote in all 50 states.

Although Native Americans were finally recognized as "citizens" of the United States in 1924, the overall impact on their rights was minimal. Under the act, Native Americans still retained their tribal affiliations and rights to tribal property. This part created confusion over Native American rights. It led future Government officials to believe that Native Americans were not full American citizens, and therefore not entitled to all of their rights.

Many tribes remained as wards of the Government, and the right to vote was slow to arrive for Native Americans in certain states. It would be decades before Native Americans were allowed to vote in all 50 states.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 299828

Full Citation: Act of June 2, 1924, Public Law 68-175, 43 STAT 253, which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians.; 6/2/1924; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/indian-citizenship-act, April 19, 2024]Act of June 2, 1924, Public Law 68-175, 43 STAT 253, which authorized the Secretary of the Interior to issue certificates of citizenship to Indians.

Page 1

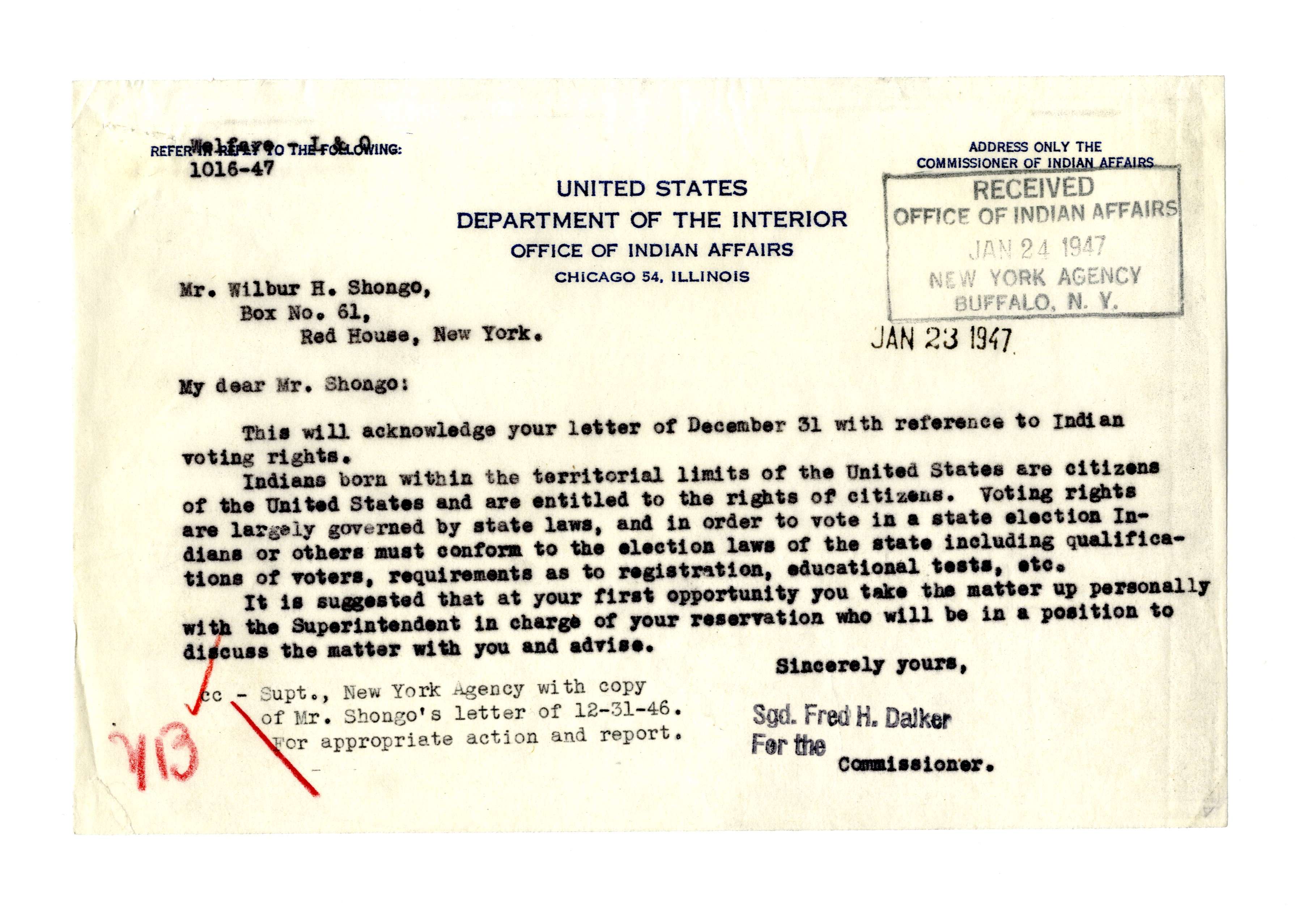

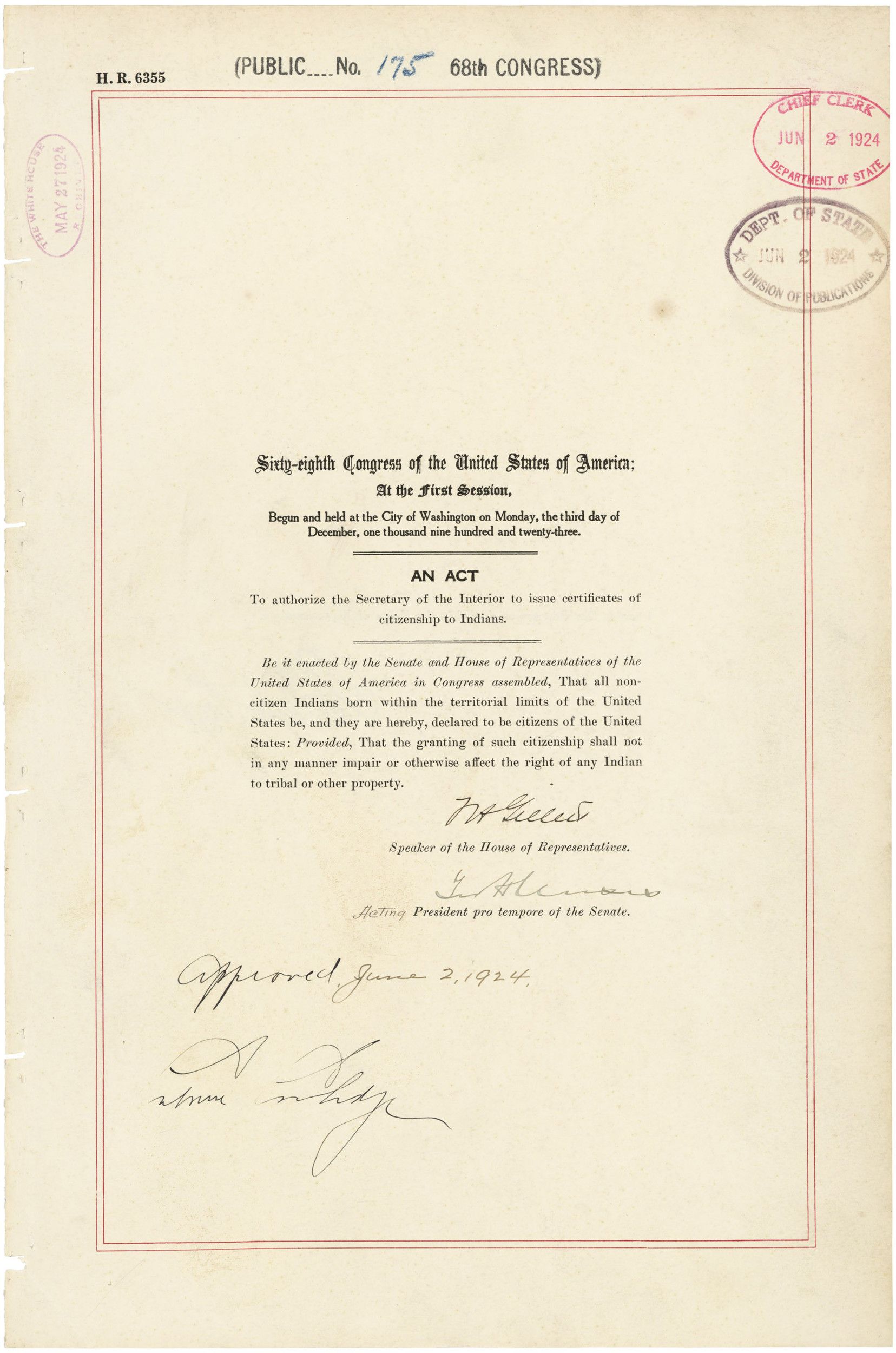

Document

Letter to Wilbur H. Shongo from Fred H. Dalker about American Indian Voting Rights

1/23/1947

In this letter to Wilbur H. Shongo, an official at the Office of Indian Affairs responds to a question regarding the voting rights of American Indians in New York.

Voting rights are largely governed by states and citizenship status. American Indians were not universally granted citizenship until 1924, and states interpreted voting rights differently. Some states didn't extend suffrage to American Indians until well into the 20th century.

American Indians were able to vote in New York State in 1947. It was not until 1962, however, that the final state, Utah, removed restrictions that prevented American Indians from voting.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 focused primarily on enfranchising African Americans in the South, but the act and its extensions also safeguarded the voting rights of many other minority Americans. This was further expanded by the Voting Rights Act of 1975 which aimed to protect women and men in language minorities, including American Indians, from discrimination at the polls.

Voting rights are largely governed by states and citizenship status. American Indians were not universally granted citizenship until 1924, and states interpreted voting rights differently. Some states didn't extend suffrage to American Indians until well into the 20th century.

American Indians were able to vote in New York State in 1947. It was not until 1962, however, that the final state, Utah, removed restrictions that prevented American Indians from voting.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 focused primarily on enfranchising African Americans in the South, but the act and its extensions also safeguarded the voting rights of many other minority Americans. This was further expanded by the Voting Rights Act of 1975 which aimed to protect women and men in language minorities, including American Indians, from discrimination at the polls.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1793 - 1999.

Full Citation: Letter to Wilbur H. Shongo from Fred H. Dalker about American Indian Voting Rights; 1/23/1947; Tribal Relations- General (NY Indians); General Records, 1938 - 1949 (NAI #4662241); Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, 1793 - 1999, ; National Archives at New York, New York, NY. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/letter-american-indian-voting-rights, April 19, 2024]Letter to Wilbur H. Shongo from Fred H. Dalker about American Indian Voting Rights

Page 1

Document

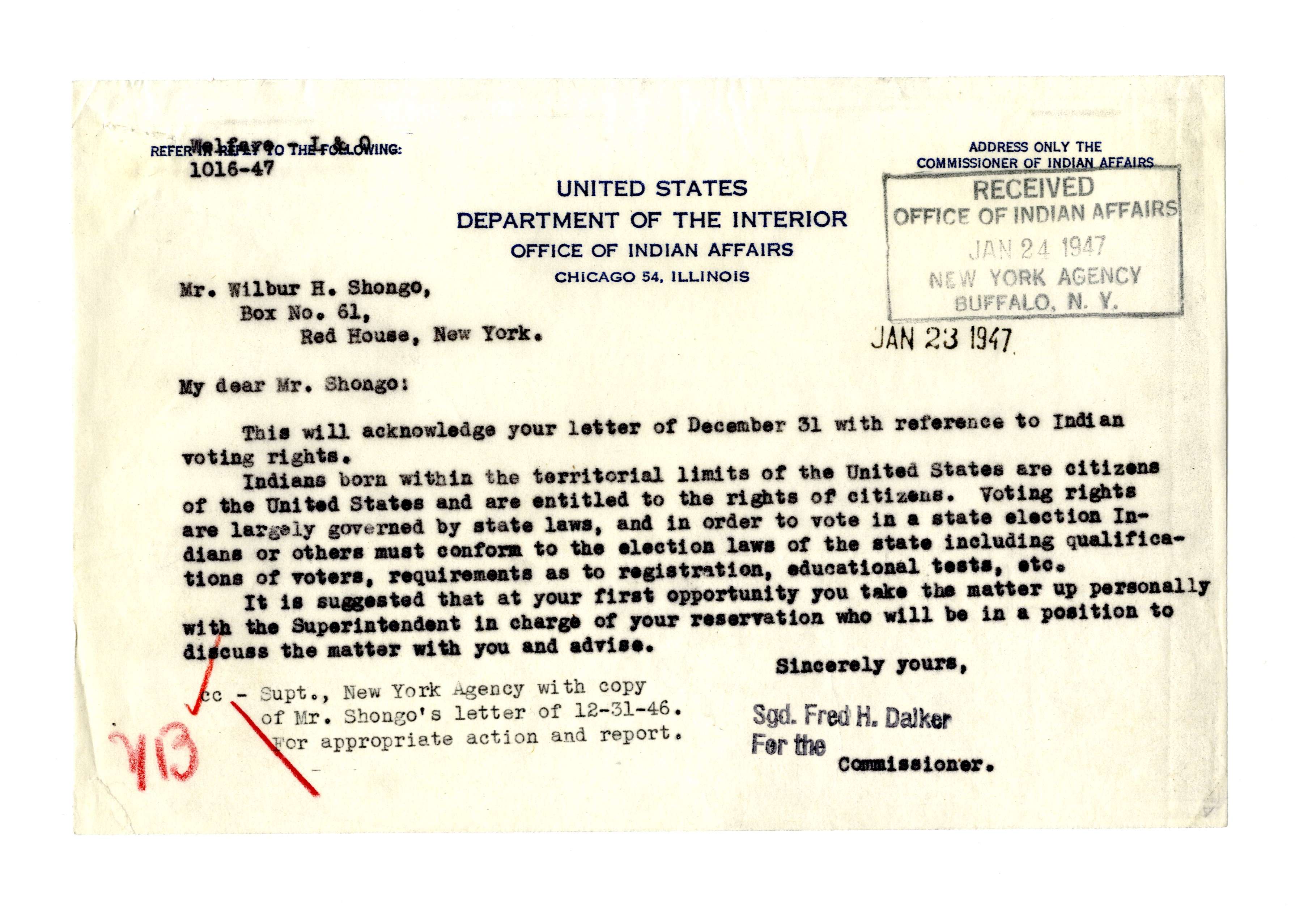

San Bruno, California. Entering Recreational Hall where election is being held for Councilman...

6/16/1942

The civil rights of Japanese immigrants and Japanese-descended U.S. citizens were violated when they were forcibly moved first to "assembly centers" and then to "relocation centers" (also known as "internment camps") during World War II. Nevertheless, all male and female adult internees were allowed to vote for camp advisory council at the Tanforan Assembly Center—a first for immigrants from Japan, who generally lacked voting rights because they could not naturalize and become American citizens. After World War II, citizenship and voting rights gradually opened to Asian immigrants.

The original caption for this image, taken by photographer Dorothea Lange for the War Relocation Authority, reads: San Bruno, California. Entering Recreational Hall where election is being held for Councilman. A general election for five members of the Tanforan Assembly Center Advisory Council is being held on this day. The Issei have never been able to vote before because of American naturalization laws.

The original caption for this image, taken by photographer Dorothea Lange for the War Relocation Authority, reads: San Bruno, California. Entering Recreational Hall where election is being held for Councilman. A general election for five members of the Tanforan Assembly Center Advisory Council is being held on this day. The Issei have never been able to vote before because of American naturalization laws.

This primary source comes from the Records of the War Relocation Authority.

National Archives Identifier: 537899

Full Citation: Photograph 210-G-C592; San Bruno, California. Entering Recreational Hall where election is being held for Councilman...; 6/16/1942; Central Photographic File of the War Relocation Authority, 1942 - 1945; Records of the War Relocation Authority, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/tanforan-vote, April 19, 2024]San Bruno, California. Entering Recreational Hall where election is being held for Councilman...

Page 1

Document

Photograph of President Lyndon Johnson Signs the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr., with Other Civil Rights Leaders in the Capitol Rotunda, Washington, DC

8/6/1965

This photograph shows President Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders look on, in the President's Room of the U.S. Capitol in Washington, DC.

This primary source comes from the Collection LBJ-WHPO: White House Photo Office Collection.

National Archives Identifier: 2803443

Full Citation: Photograph A1030-8A; Photograph of President Lyndon Johnson Signs the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr., with Other Civil Rights Leaders in the Capitol Rotunda, Washington, DC; 8/6/1965; Johnson White House Photographs, 11/22/1963 - 1/20/1969; Collection LBJ-WHPO: White House Photo Office Collection, ; Lyndon Baines Johnson Library, Austin, TX. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/lbj-signs-voting-rights-act, April 19, 2024]Photograph of President Lyndon Johnson Signs the Voting Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr., with Other Civil Rights Leaders in the Capitol Rotunda, Washington, DC

Page 1

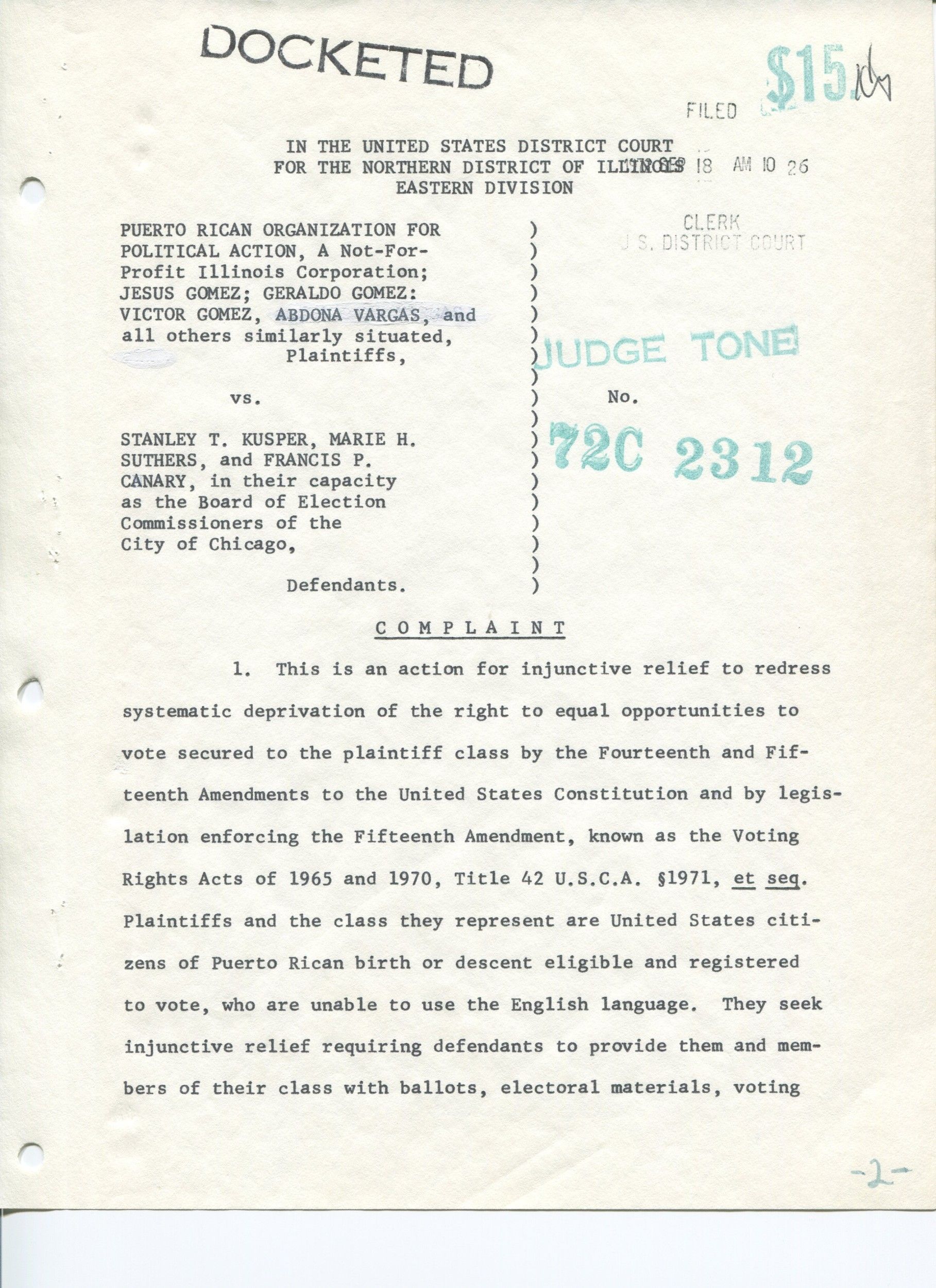

Document

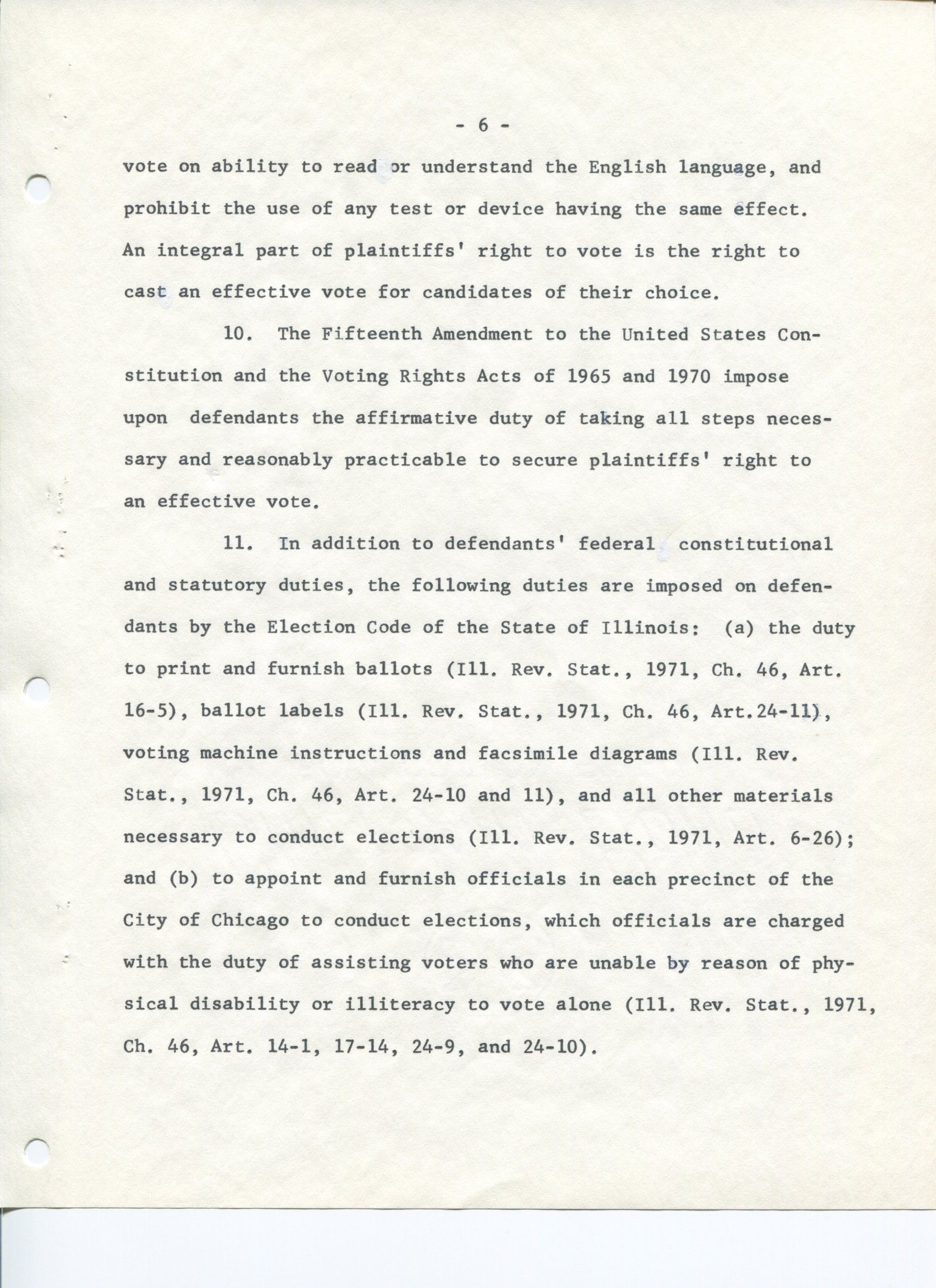

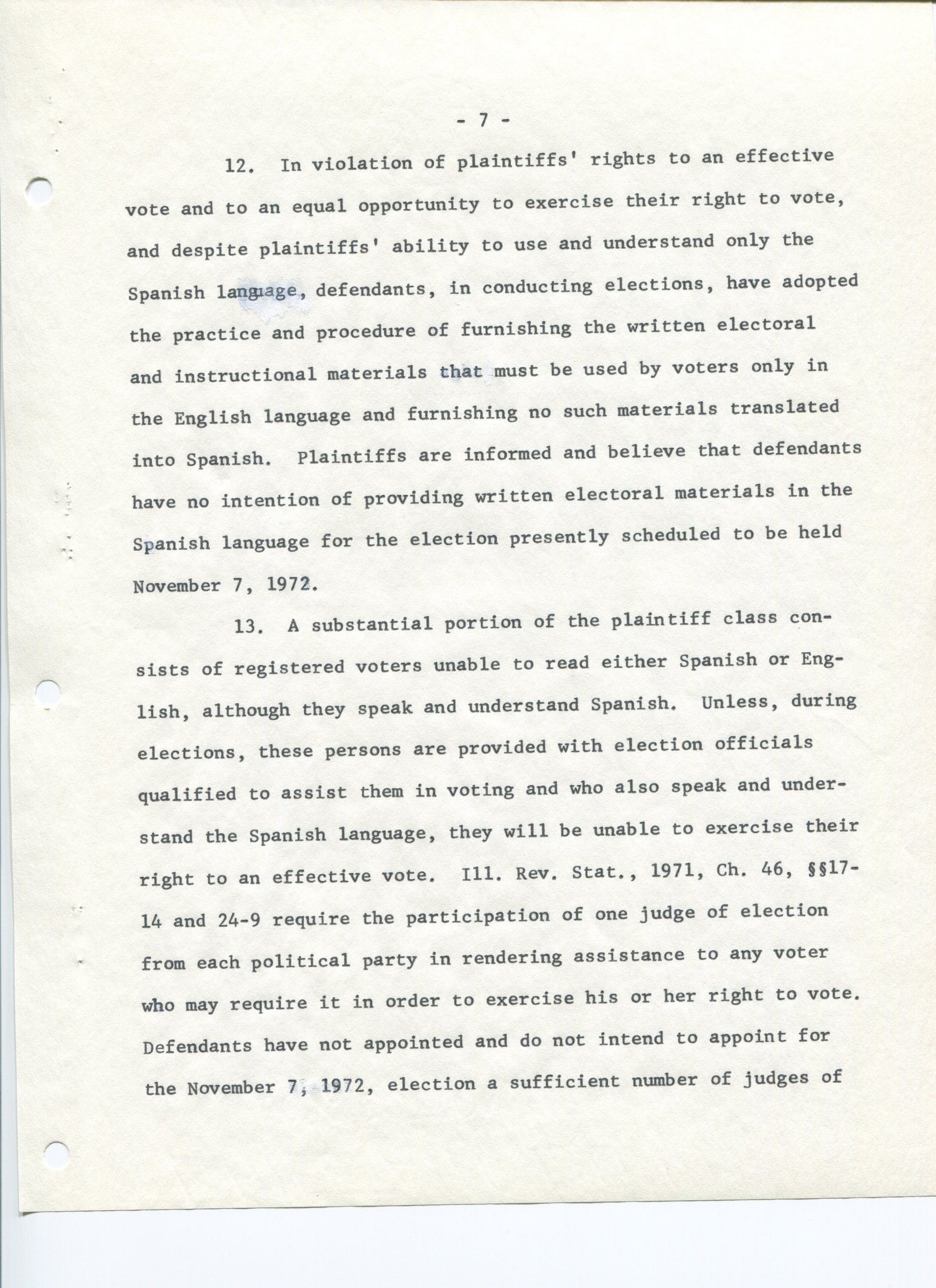

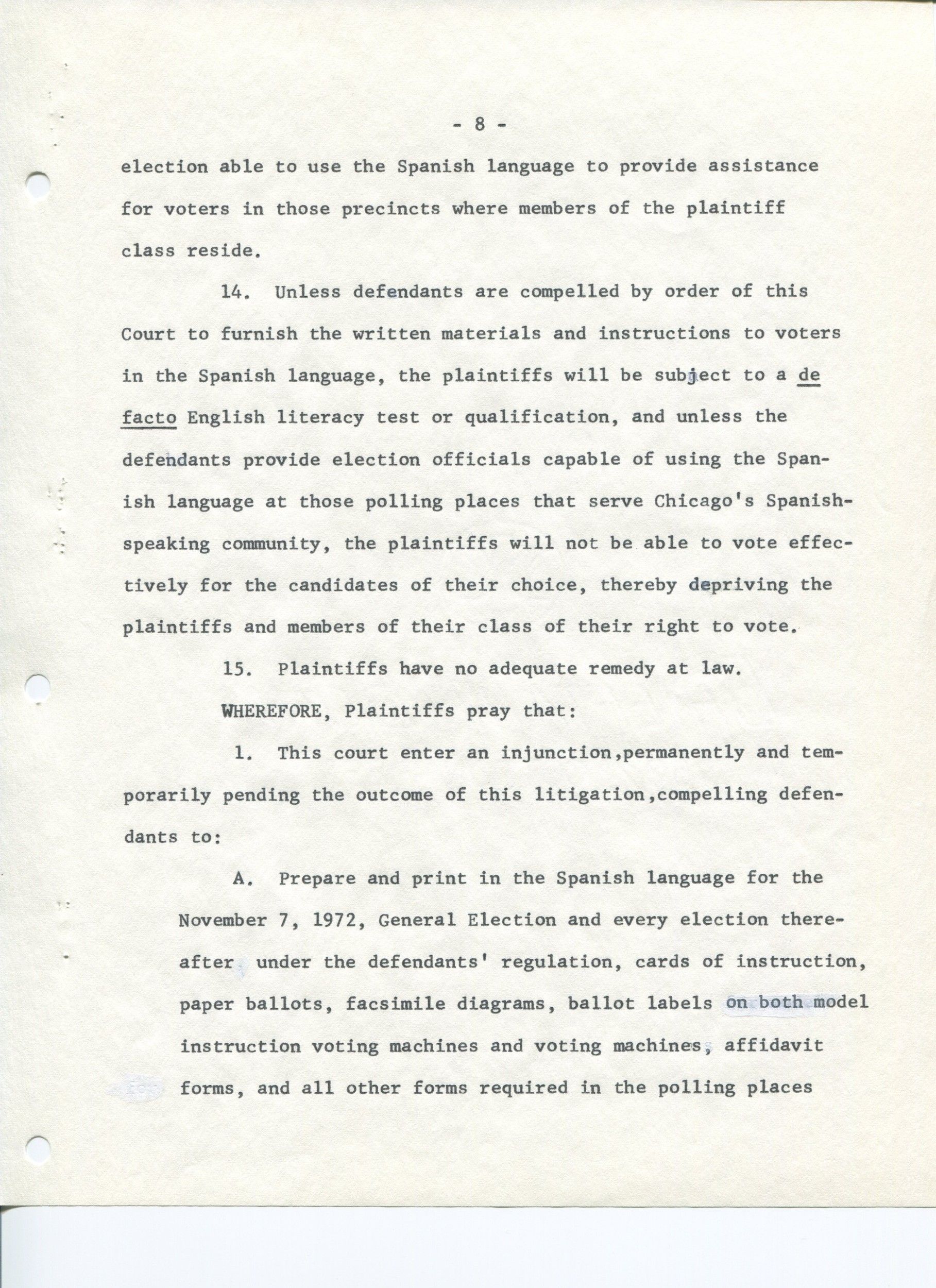

Complaint

9/18/1972

This is the complaint filed in the case Puerto Rican Organization for Political Action, Jesus Gomez, Geraldo Gomez, Victor Gomez, Abdona Vargas, and other others similarly situated v. Stanley T. Kusper, Marie H. Suthers, and Francis P. Canary, in their capacity as the Board of Election Commissioners of the City of Chicago. This is a civil case in which the plaintiffs, Jesus Gomez, Geraldo Gomez, Victor Gomez, Abdona Vargas, and the Puerto Rican Organization for Political Action, sought to compel the defendants, the City of Chicago Board of Election Commissioners, to provide voting assistance in the Spanish language to United States citizens of Puerto Rican birth, who were unable to use the English language.

With their complaint filed on September 18, 1972, the plaintiffs also filed a motion for preliminary injunctive relief in connection with the November 7, 1972 General Election in Chicago, Illinois. The case file includes the complaint, motions, affidavits, exhibits, transcript of proceedings, and amici curiae memorandum. This case was appealed to the Seventh Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2014 Summer Workshop in Chicago.

With their complaint filed on September 18, 1972, the plaintiffs also filed a motion for preliminary injunctive relief in connection with the November 7, 1972 General Election in Chicago, Illinois. The case file includes the complaint, motions, affidavits, exhibits, transcript of proceedings, and amici curiae memorandum. This case was appealed to the Seventh Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

This document was digitized by teachers in our Primarily Teaching 2014 Summer Workshop in Chicago.

This primary source comes from the Records of District Courts of the United States.

National Archives Identifier: 12008891

Full Citation: Complaint; 9/18/1972; Puerto Rican Organization for Political Action, Jesus Gomez, Geraldo Gomez, Victor Gomez, Abdona Vargas, and other others similarly situated v. Stanley T. Kusper, Marie H. Suthers, and Francis P. Canary, in their capacity as the Board of Election...; Civil Case Files, 1938 - 1995; Records of District Courts of the United States, ; National Archives at Chicago, Chicago, IL. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/complaint, April 19, 2024]Complaint

Page 1

Complaint

Page 2

Complaint

Page 3

Complaint

Page 4

Complaint

Page 5

Complaint

Page 6

Complaint

Page 7

Complaint

Page 8

Complaint

Page 9

Complaint

Page 10

Document

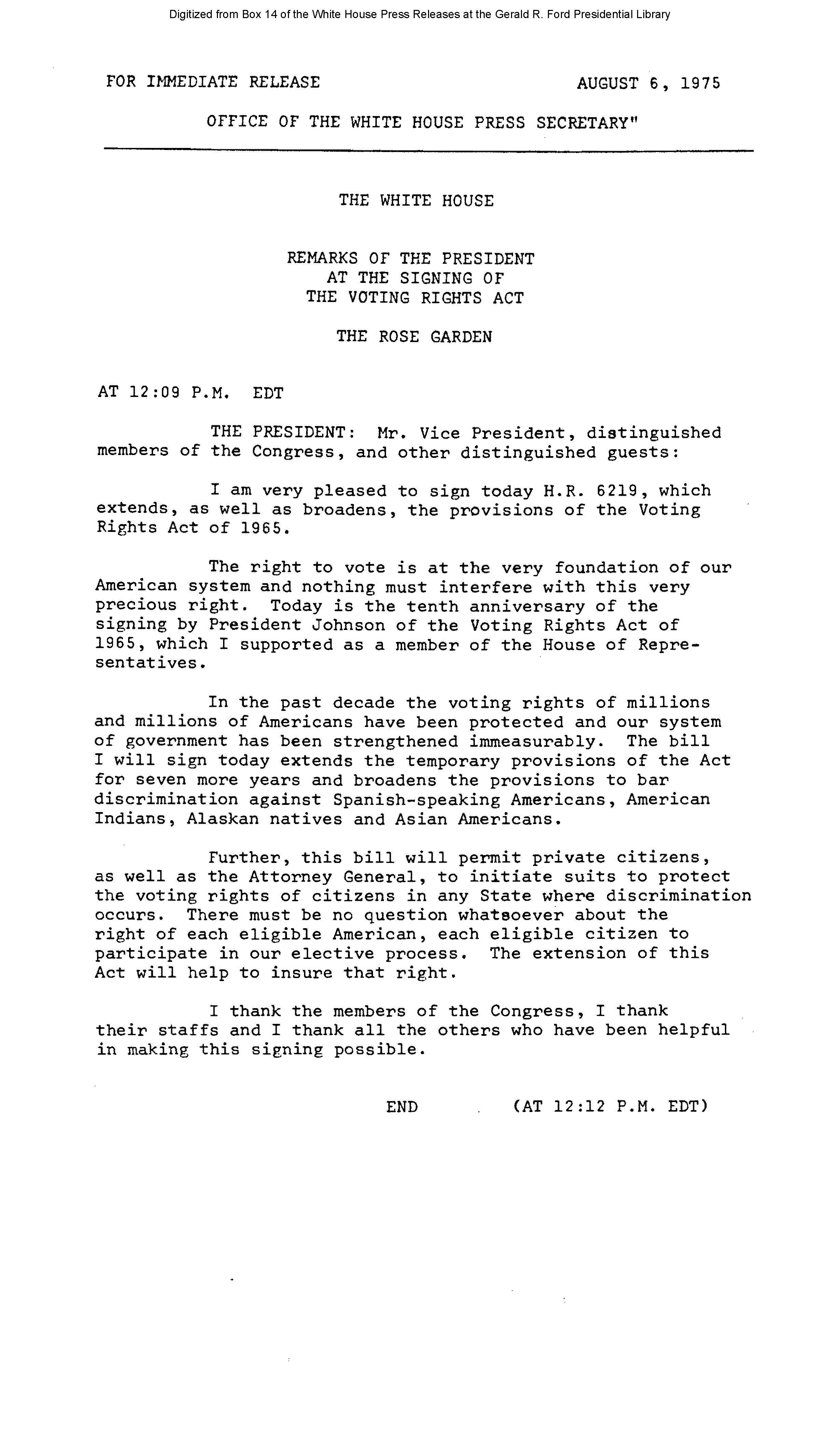

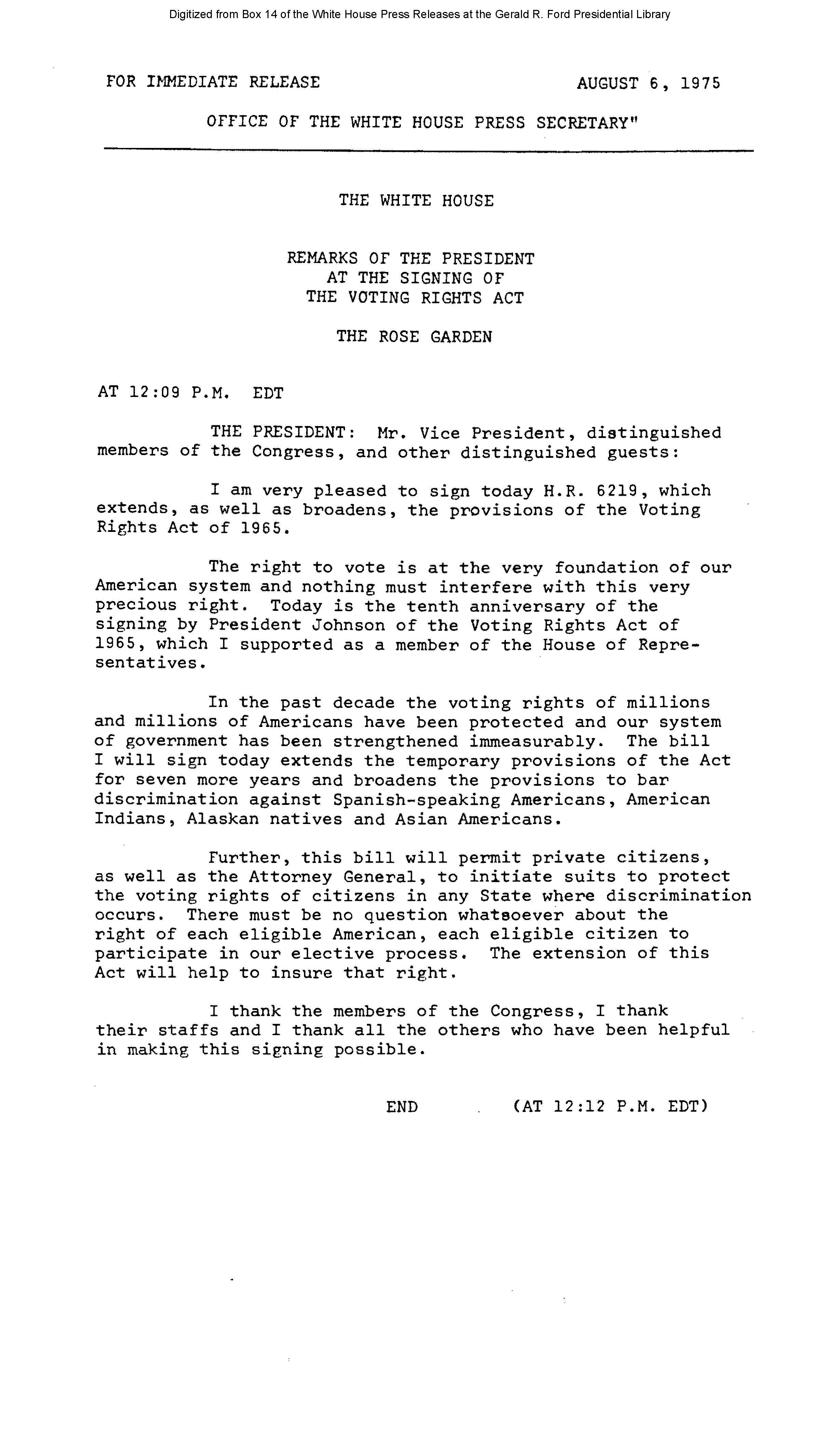

Remarks of the President at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act [Ford Speech or Statement]

8/6/1975

The Voting Rights Act of 1975, an extension of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, aimed to protect women and men in language minorities – including American Indians, Asian Americans, Alaskan Natives, and those of Spanish heritage – from discrimination at the polls. It required bilingual ballots and election materials in areas with significant minority populations and permanently banned literacy tests.

This White House press release shows President Gerald Ford's remarks upon signing the legislation on August 6, 1975.

This White House press release shows President Gerald Ford's remarks upon signing the legislation on August 6, 1975.

Transcript

For Immediate ReleaseAugust 6, 1975

Office of the White House Press Secretary"

The White House

Remarks of the President at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act

The Rose Garden

At 12:09 P.M. EDT

THE PRESIDENT: Mr. Vice President, distinguished members of the Congress, and other distinguished guests:

I am very pleased to sign today H.R. 6219, which extends, as well as broadens, the provisions of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

The right to vote is at the very foundation of our American system and nothing must interfere with this very precious right. Today is the tenth anniversary of the signing by President Johnson of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which I supported as a member of the House of Representatives.

In the past decade the voting rights of millions and millions of Americans have been protected and our system of government has been strengthened immeasurably. The bill I will sign today extends the temporary provisions of the Act for seven more years and broadens the provisions to bar discrimination against Spanish-speaking Americans, American Indians, Alaskan natives and Asian Americans.

Further, this bill will permit private citizens, as well as the Attorney General, to initiate suits to protect the voting rights of citizens in any State where discrimination occurs. There must be no question whatsoever about the right of each eligible American, each eligible citizen to participate in our elective process. The extension of this Act will help to insure that right.

I thank the members of the Congress, I thank their staffs and I thank all the others who have been helpful in making this signing possible.

END

(At 12:12 P.M. EDT)

This primary source comes from the Collection GRF-0248: White House Press Releases (Ford Administration).

National Archives Identifier: 7340475

Full Citation: Remarks of the President at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act [Ford Speech or Statement]; 8/6/1975; Press Releases, August 6, 1975; Press Releases, 1974 - 1977; Collection GRF-0248: White House Press Releases (Ford Administration), ; Gerald R. Ford Library, Ann Arbor, MI. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/ford-voting-rights-act-1975, April 19, 2024]Remarks of the President at the Signing of the Voting Rights Act [Ford Speech or Statement]

Page 1