Famous American Authors and their Homes

Seeing the Big Picture

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

The photographs below show famous American authors Harriet Beecher Stowe, Mark Twain, and Washington Irving, as well as the houses where they lived. For each photograph, click on the orange "open in new window" icon to read information about each person and house. Then match each picture of the American author to their home.Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

Famous American Authors and their Homes

Seeing the Big Picture

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Consider how each document or piece of text relates to each other and create matched pairs. Write the text or document number next to its match below. Write your conclusion response in the space provided.1

2

3

1

Activity Element

2

Activity Element

3

Activity Element

4

Activity Element

5

Activity Element

6

Activity Element

Culminating Document

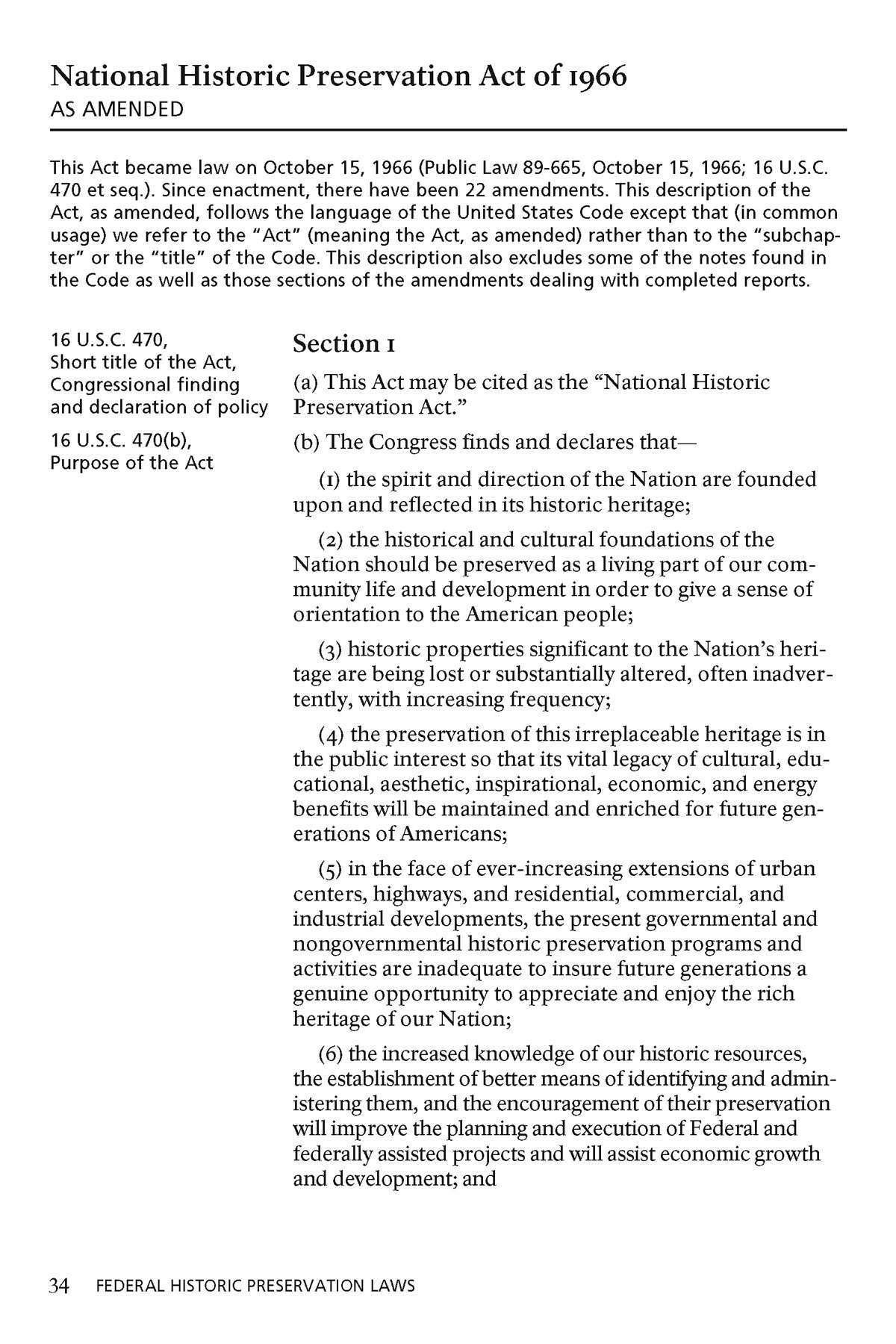

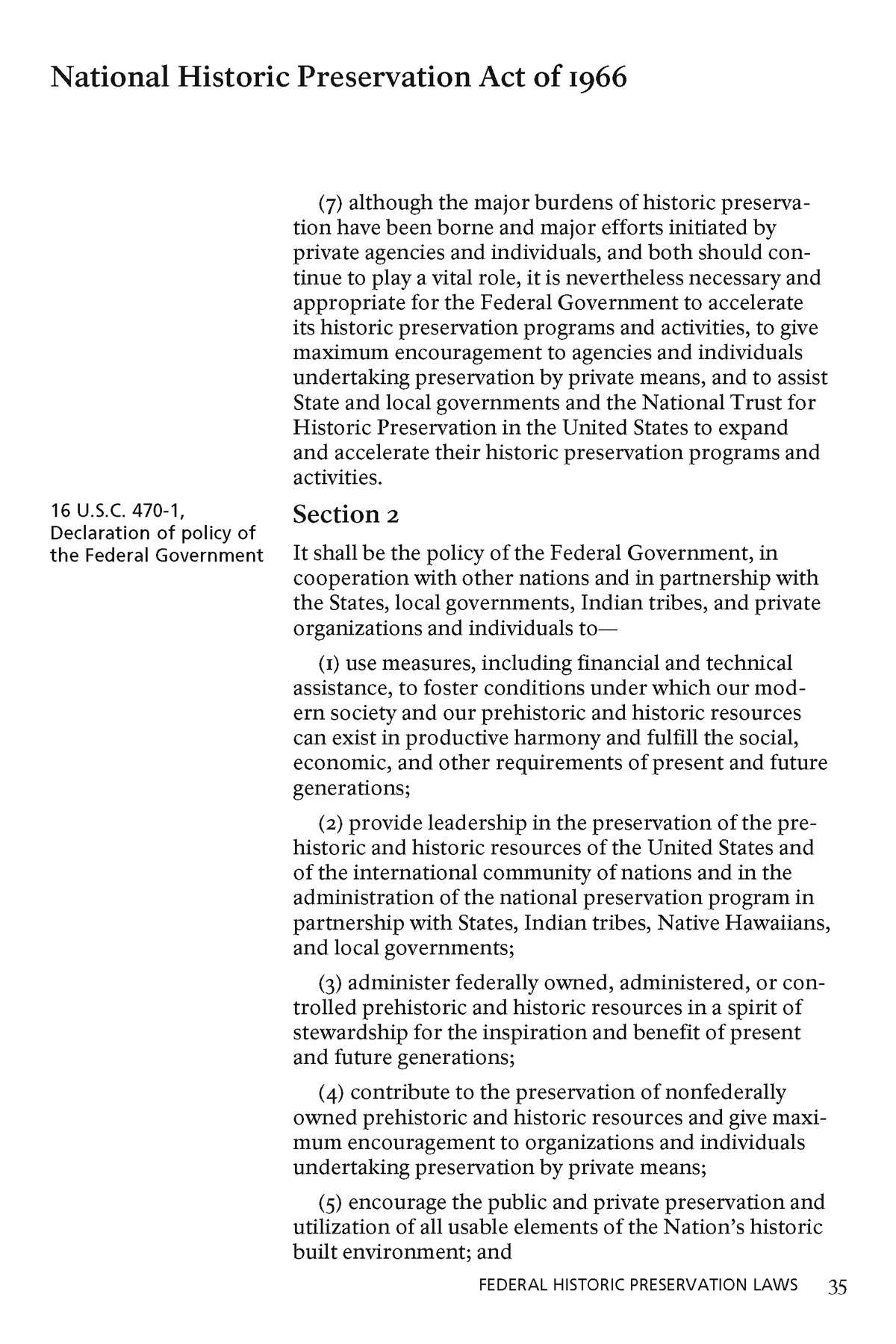

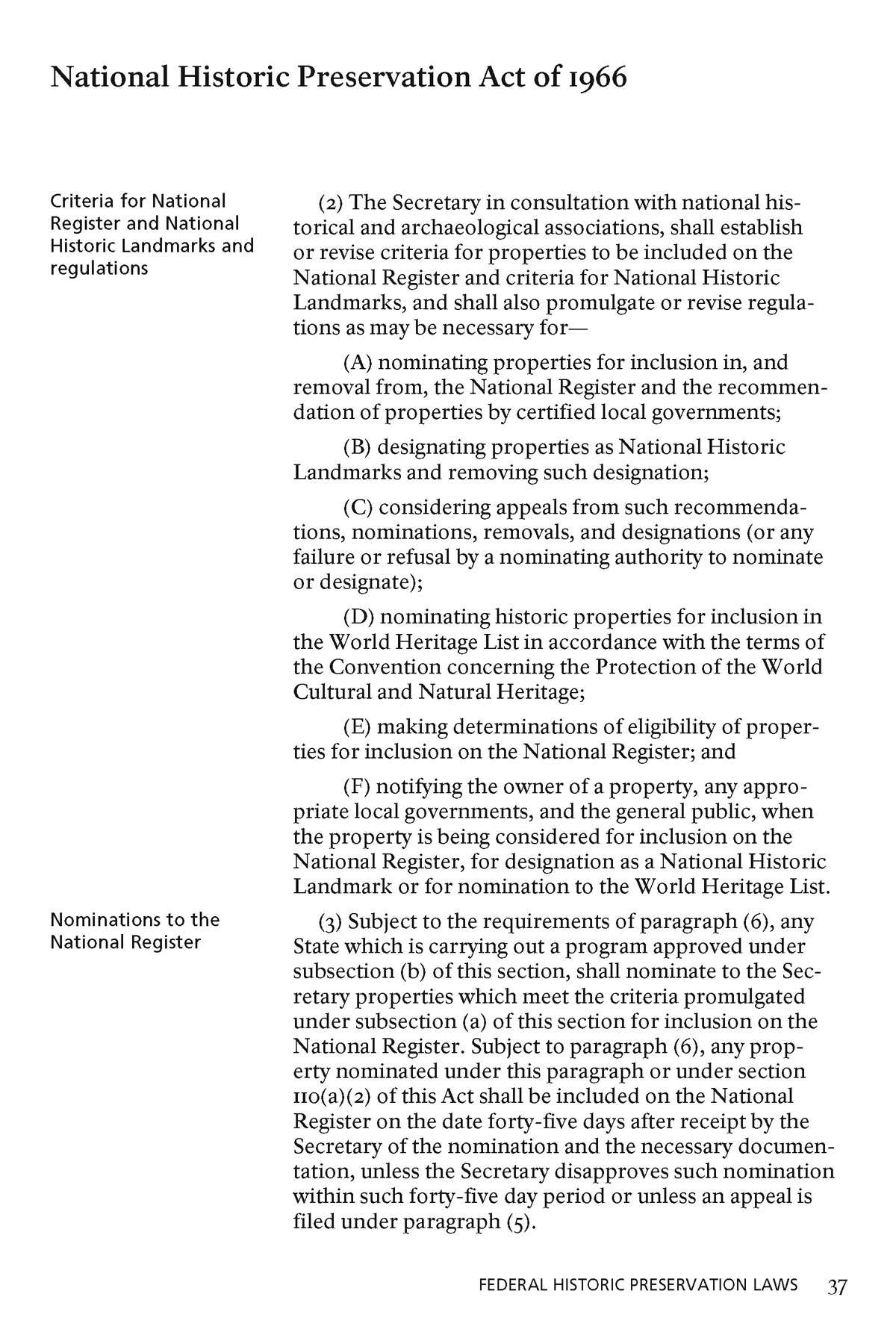

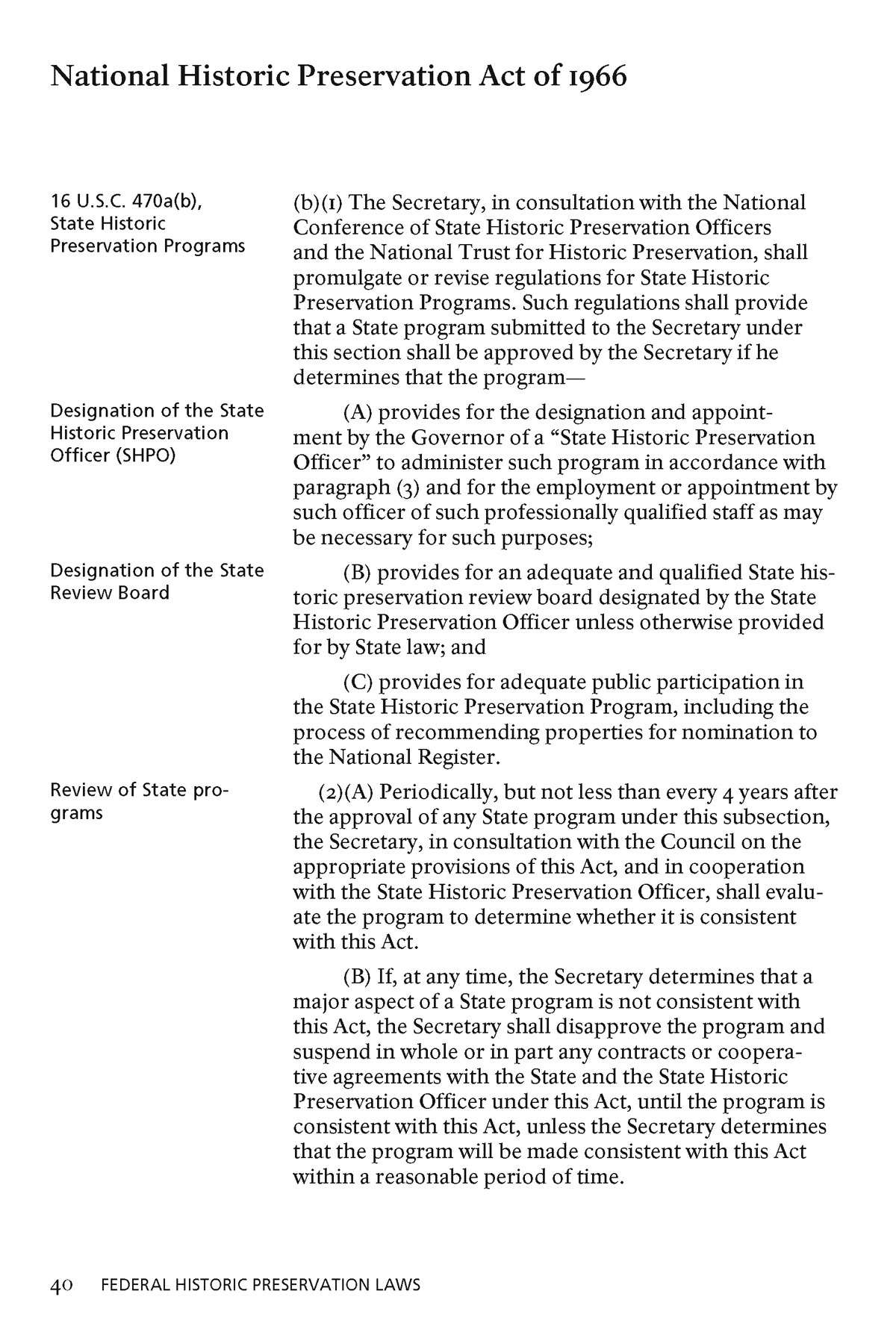

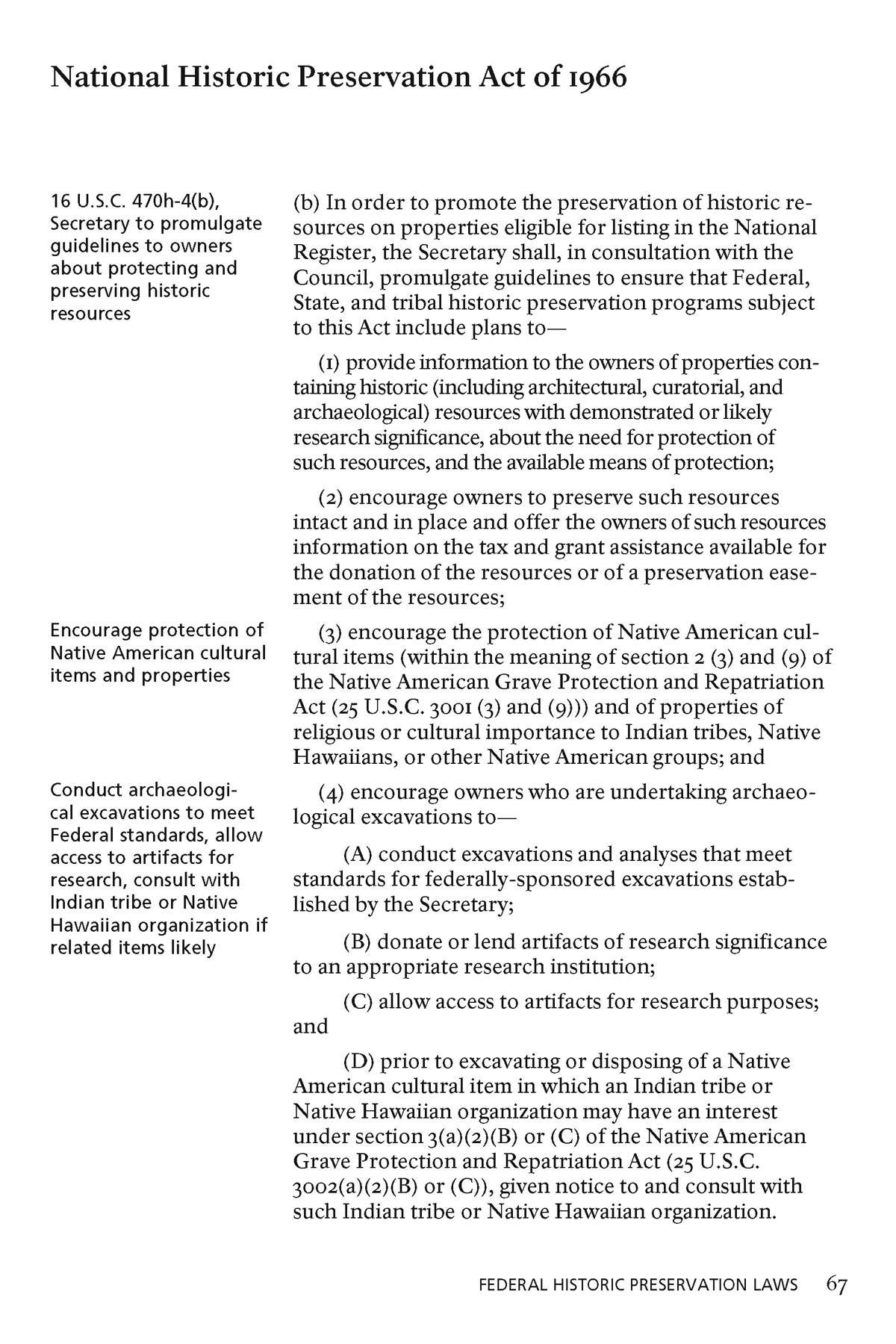

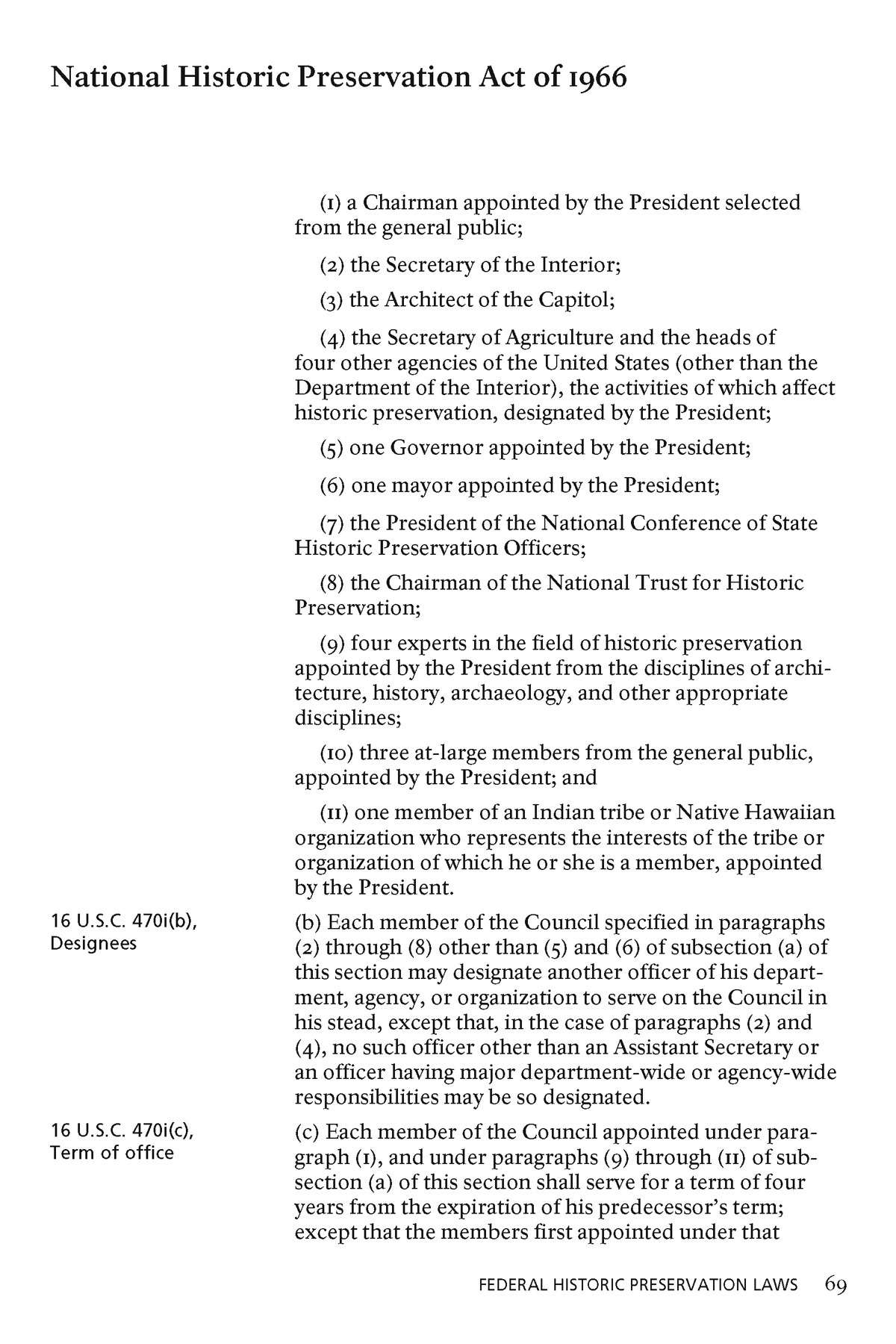

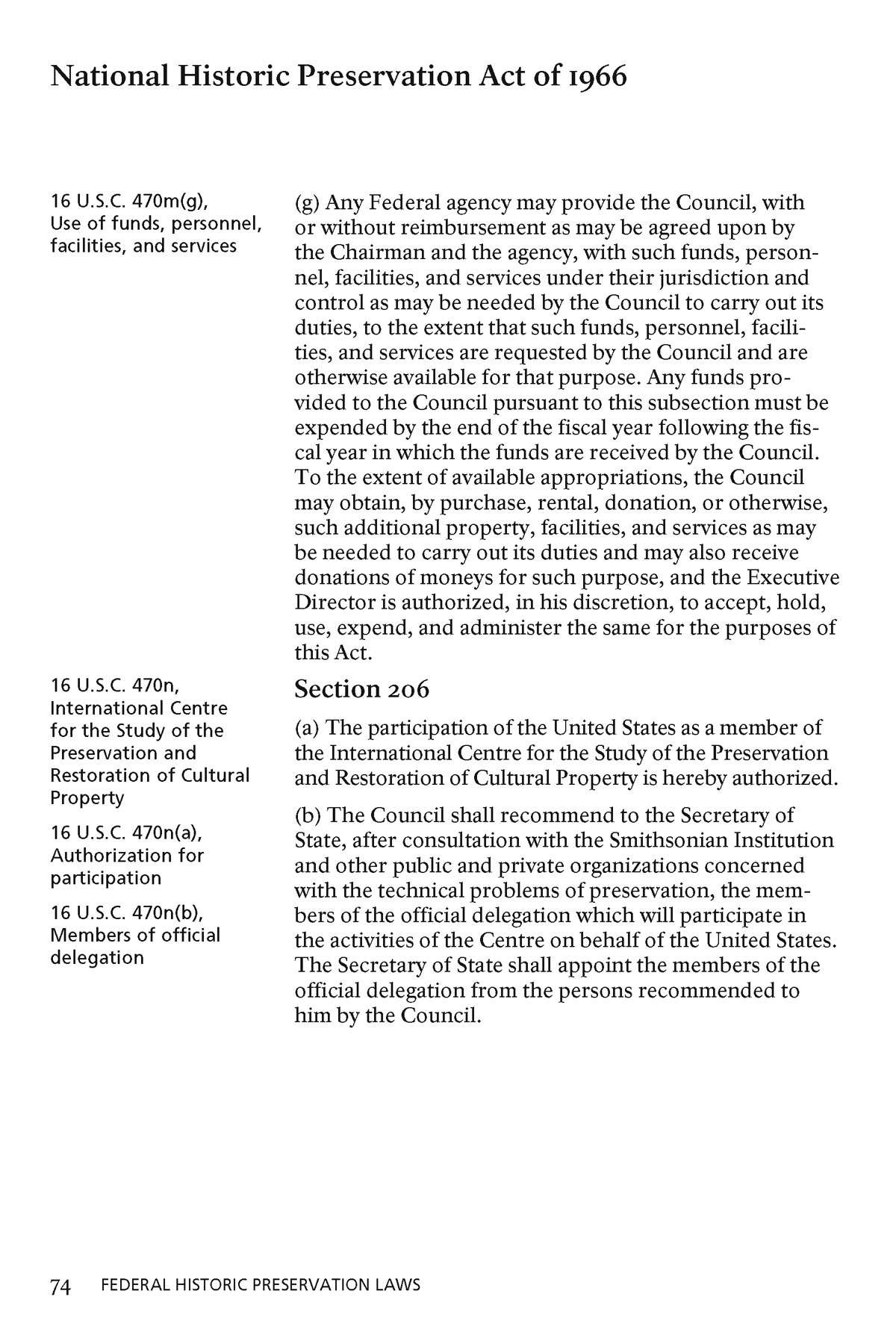

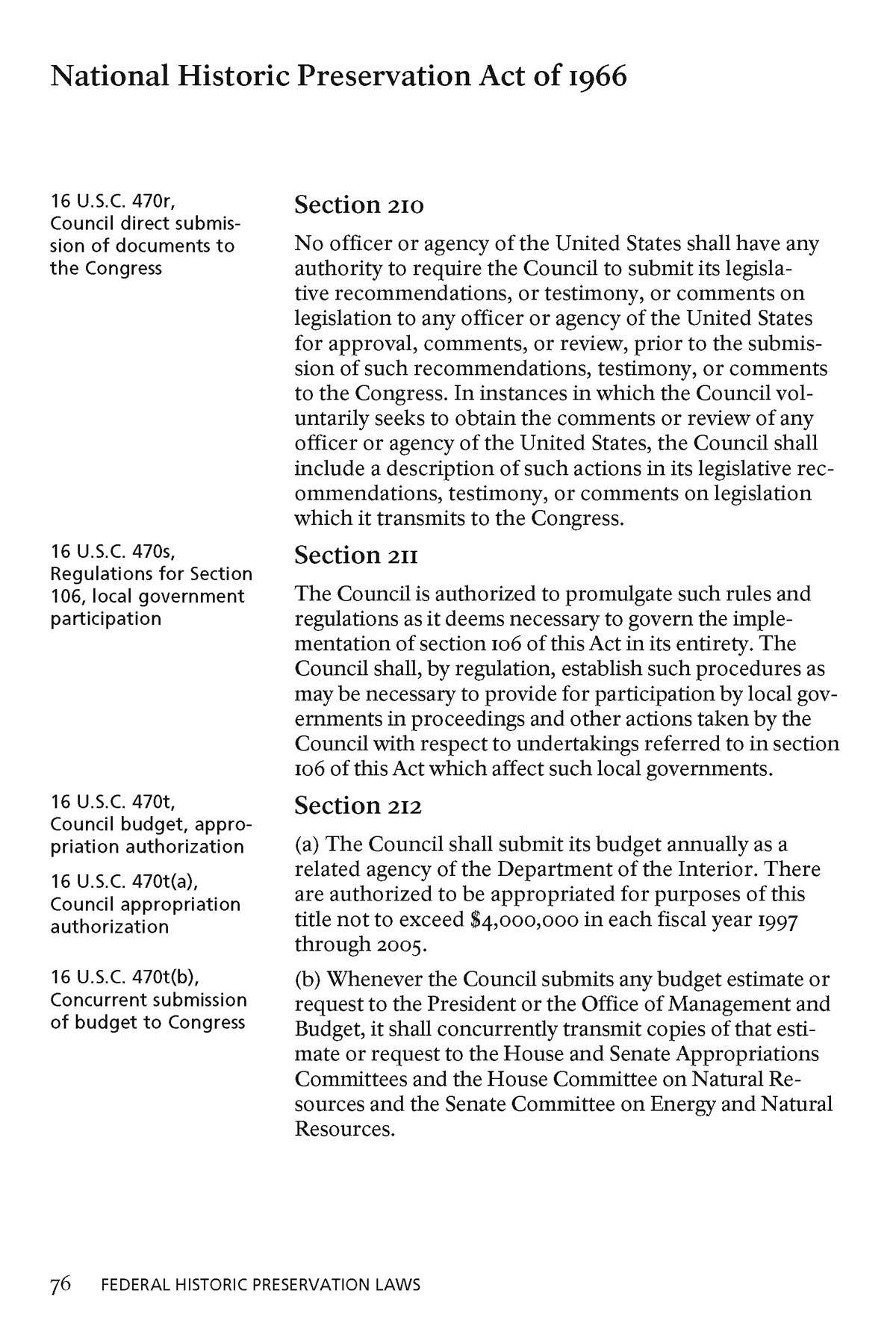

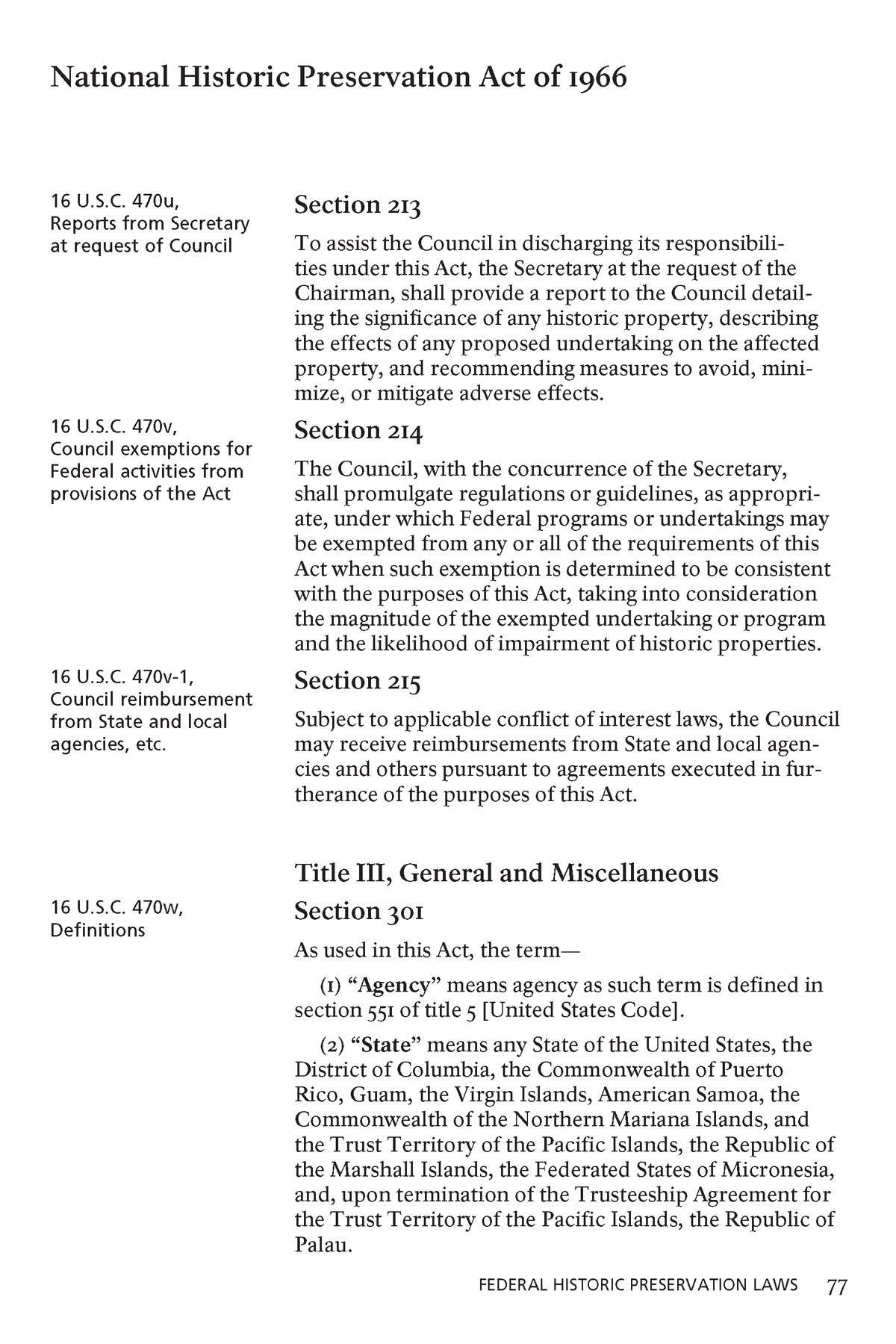

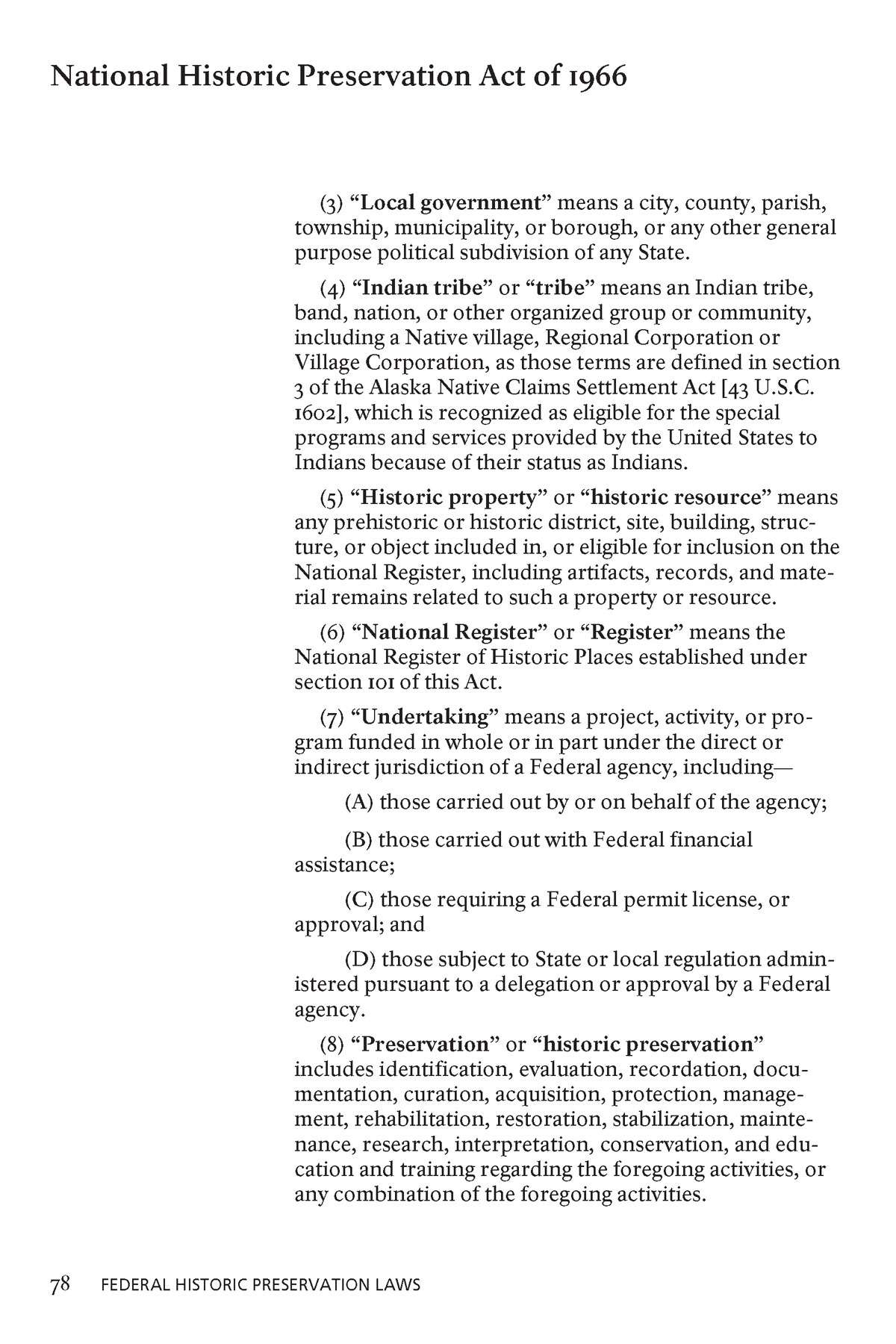

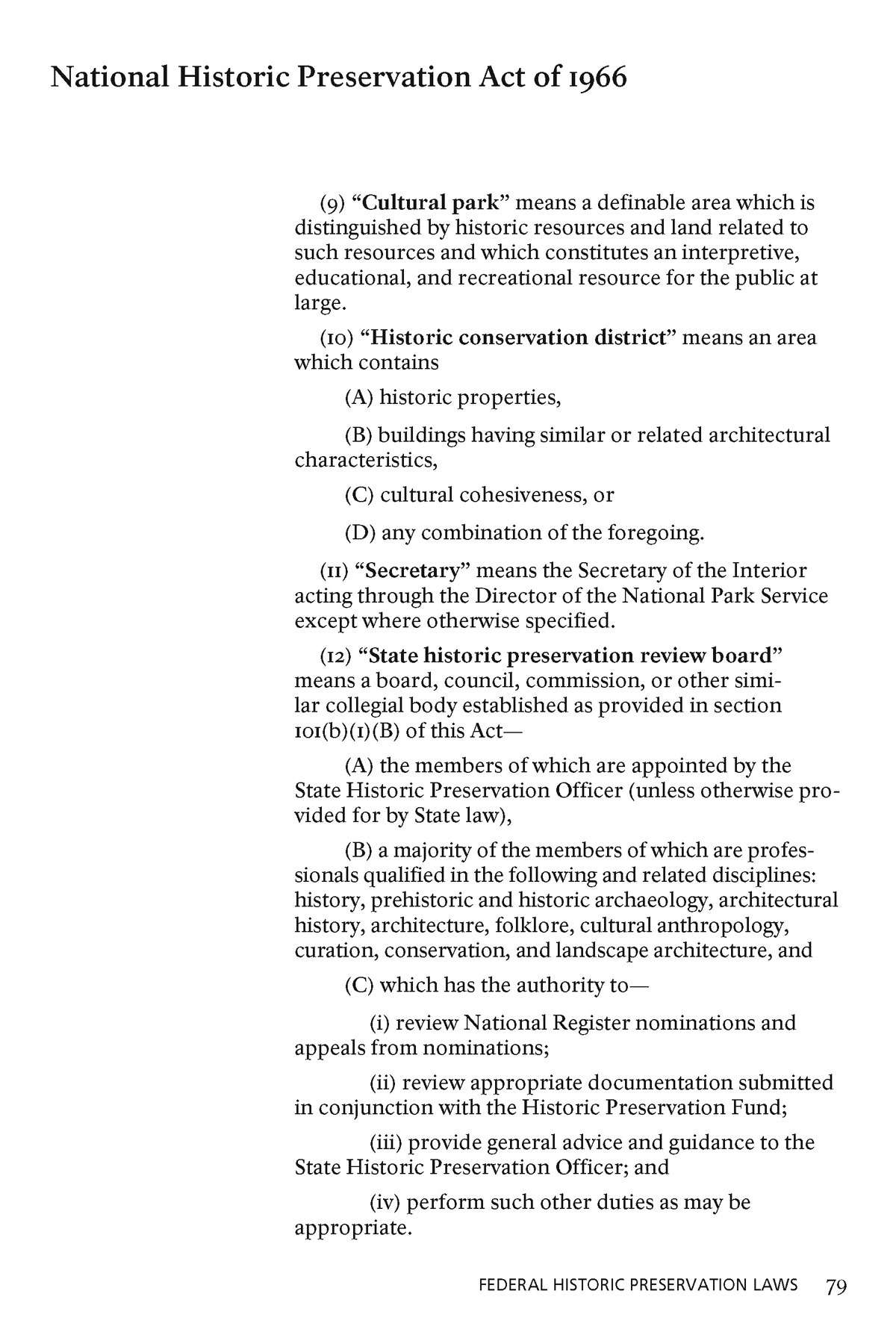

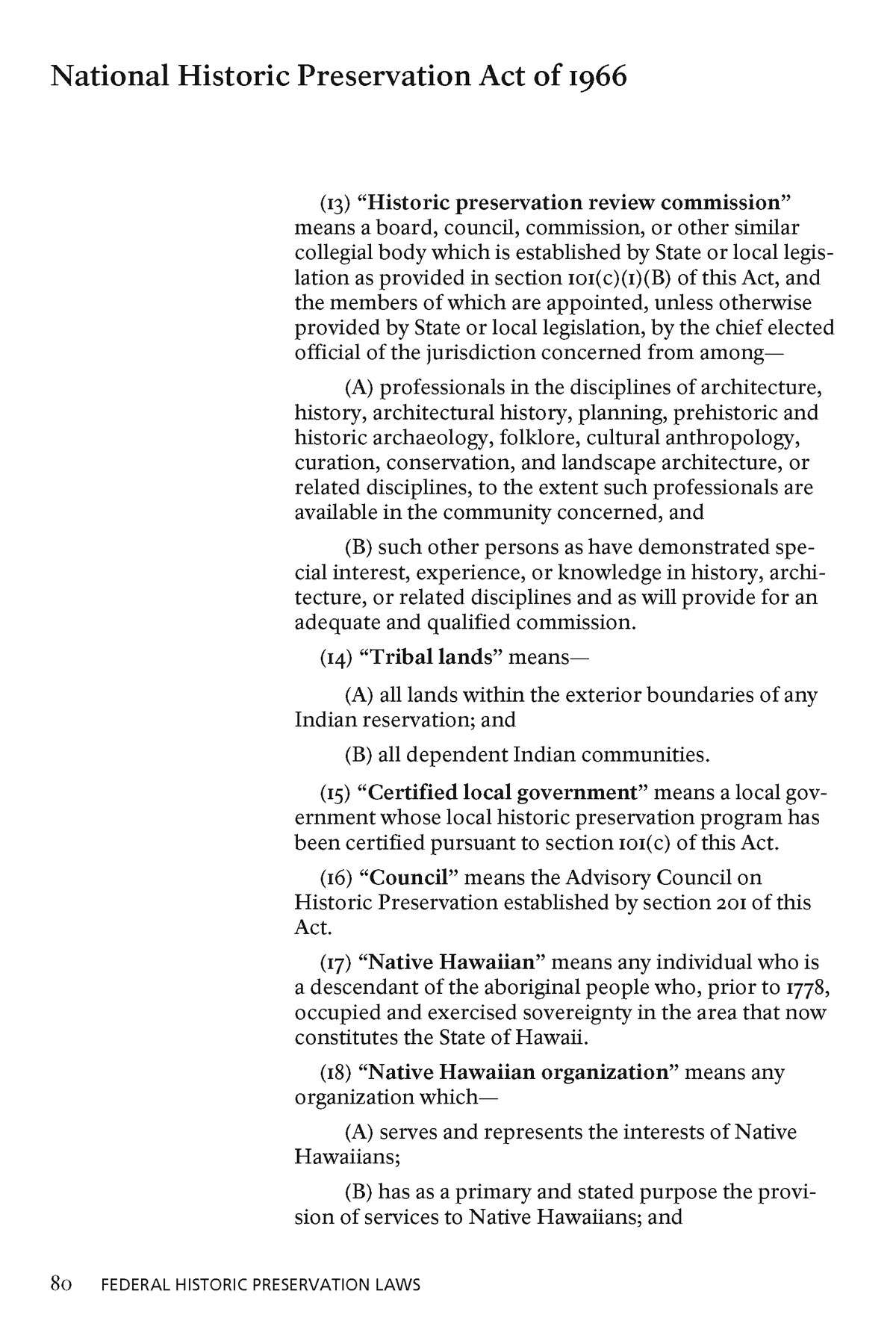

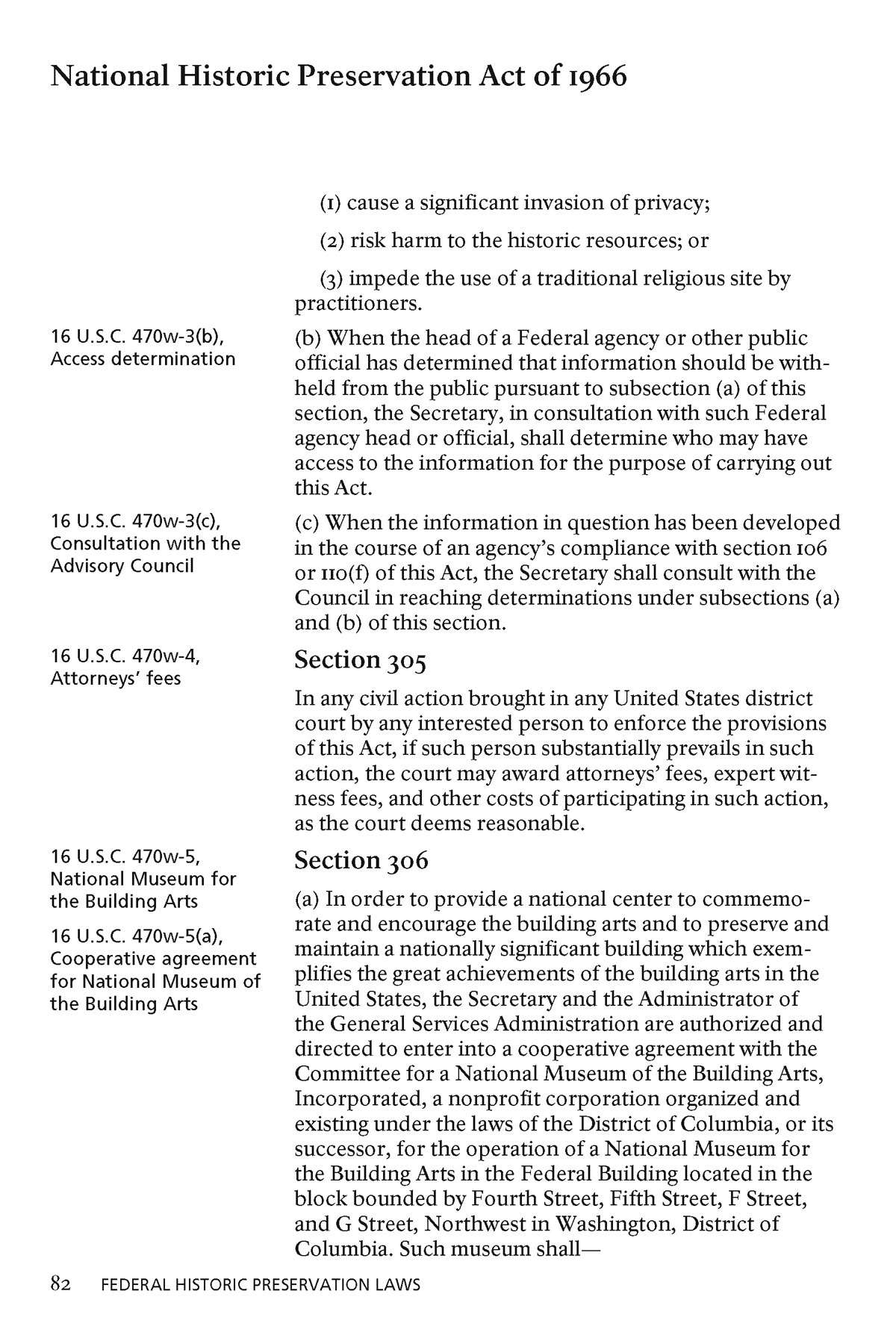

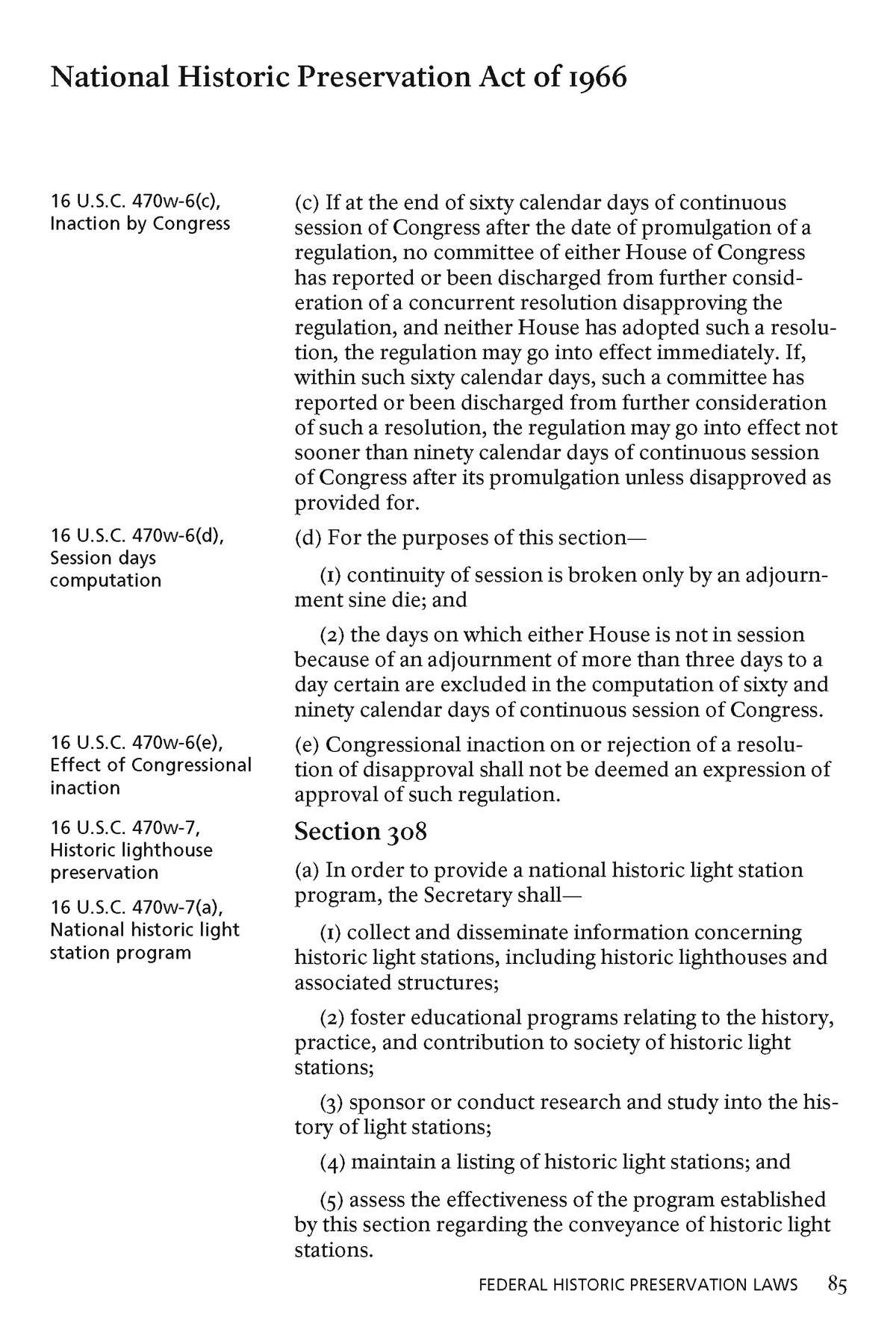

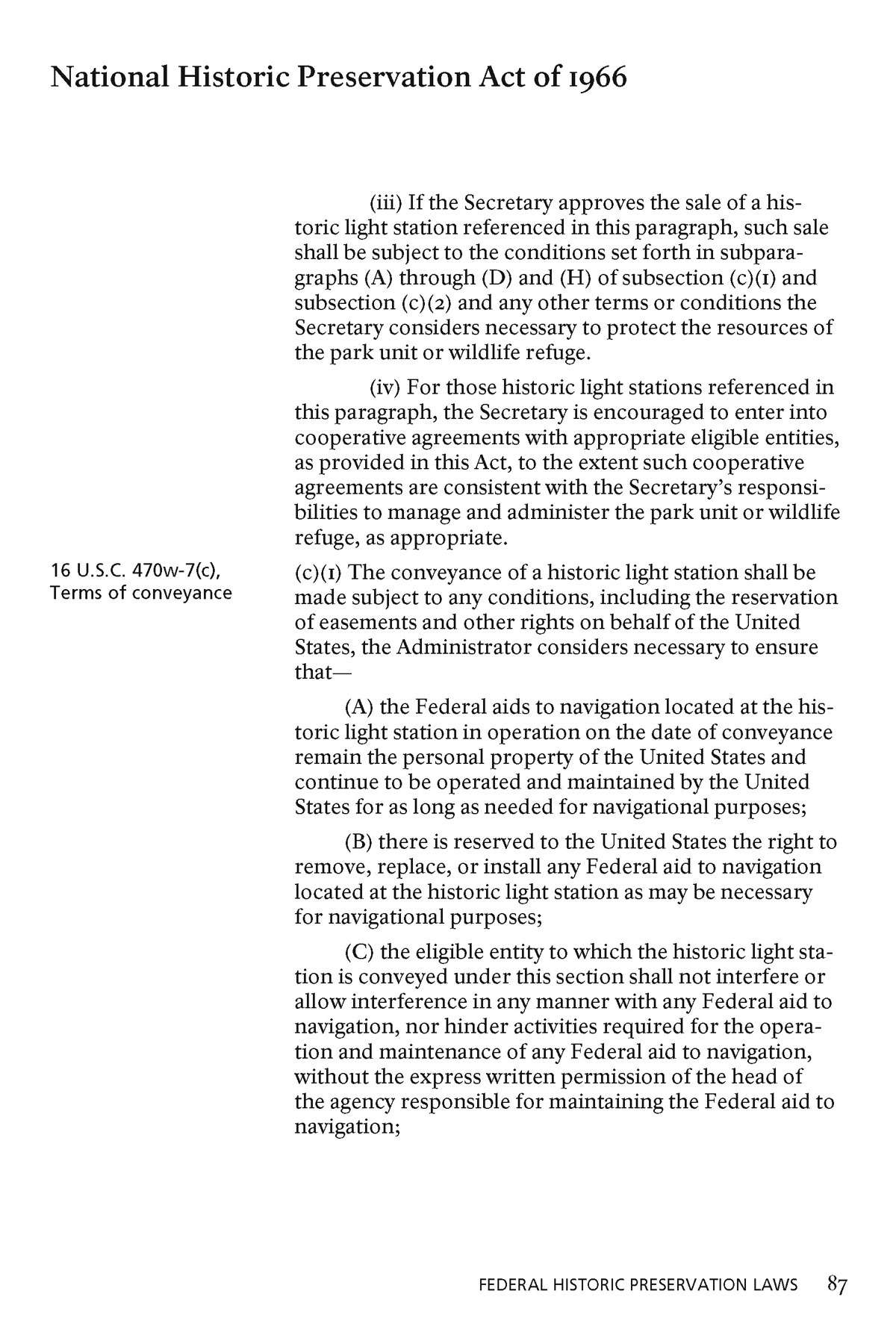

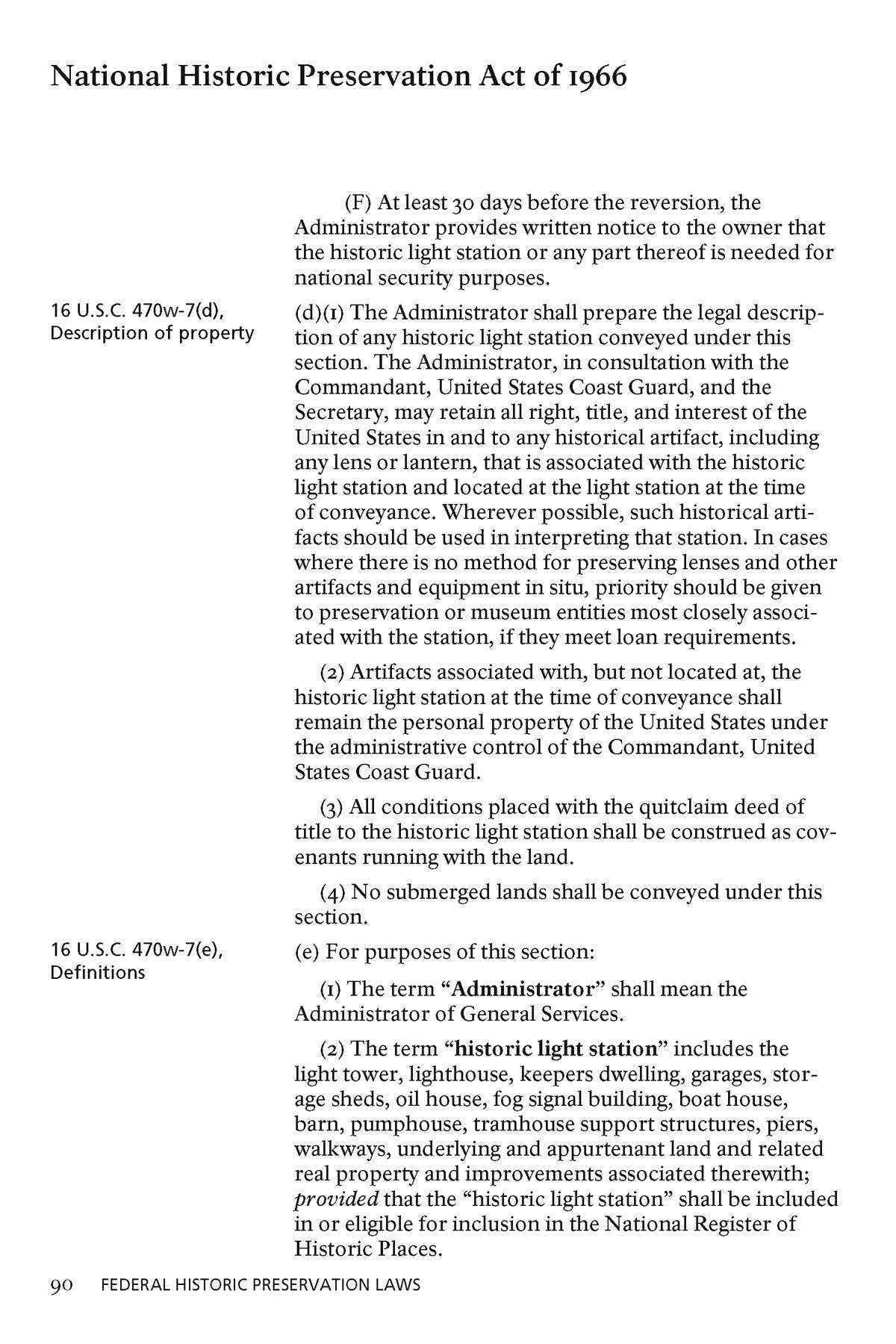

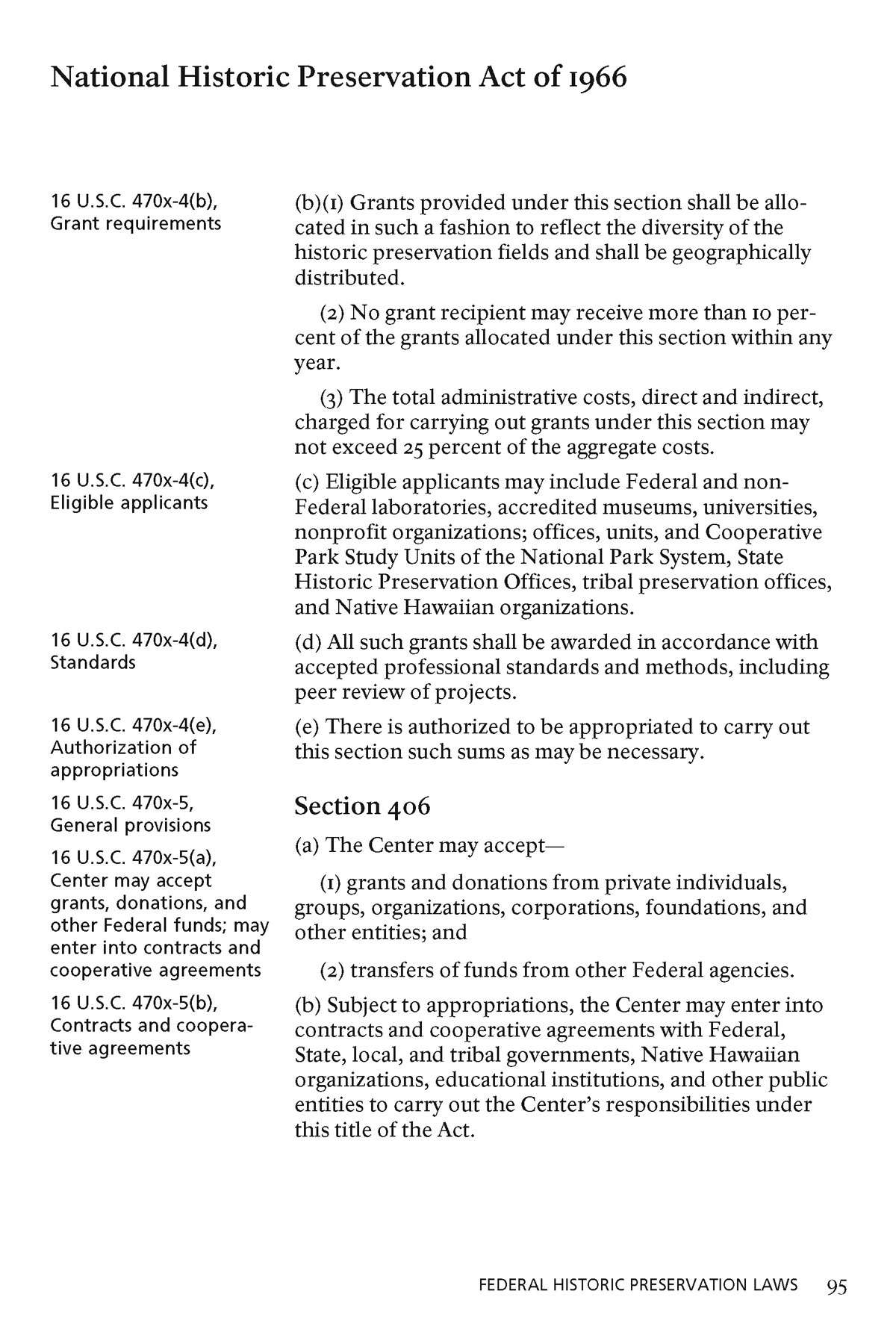

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

10/15/1966

In 1966, Congress passed the National Historic Preservation Act, the most comprehensive preservation law in U.S. history. The previous year, President Lyndon B. Johnson had convened a special committee on historic preservation. The committee's report to Congress, "With Heritage So Rich," documented the need for preservation. At that time, the National Park Service's Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) had documented 12,000 places in the United States; but by 1966, half of them had either been destroyed or damaged.

According to the National Historic Preservation Act, any federal or federally funded project that will impact a historic structure or site must be reviewed to determine if the work might harm the site. Projects also have to follow federal preservation standards.

The new law also created the President's Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and the National Register of Historic Places – an official list of important buildings and structures, districts, objects, and archeological sites. States are also required to take on responsibility for their historic sites, with each state establishing a historic preservation office and keeping an inventory of sites.

According to the National Historic Preservation Act, any federal or federally funded project that will impact a historic structure or site must be reviewed to determine if the work might harm the site. Projects also have to follow federal preservation standards.

The new law also created the President's Advisory Council on Historic Preservation and the National Register of Historic Places – an official list of important buildings and structures, districts, objects, and archeological sites. States are also required to take on responsibility for their historic sites, with each state establishing a historic preservation office and keeping an inventory of sites.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Projects.

National Archives Identifier: 206247415

Full Citation: National Historic Preservation Act of 1966; 10/15/1966; National Environmental Policy Act [NEPA] Permits Files; Permits Records, 2004 - 2015; Records of the Office of the Federal Coordinator for Alaska Natural Gas Transportation Projects, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/national-historic-preservation-act, April 24, 2024]National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 1

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 2

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 3

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 4

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 5

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 6

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 7

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 8

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 9

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 10

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 11

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 12

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 13

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 14

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 15

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 16

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 17

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 18

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 19

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 20

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 21

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 22

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 23

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 24

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 25

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 26

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 27

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 28

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 29

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 30

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 31

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 32

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 33

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 34

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 35

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 36

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 37

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 38

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 39

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

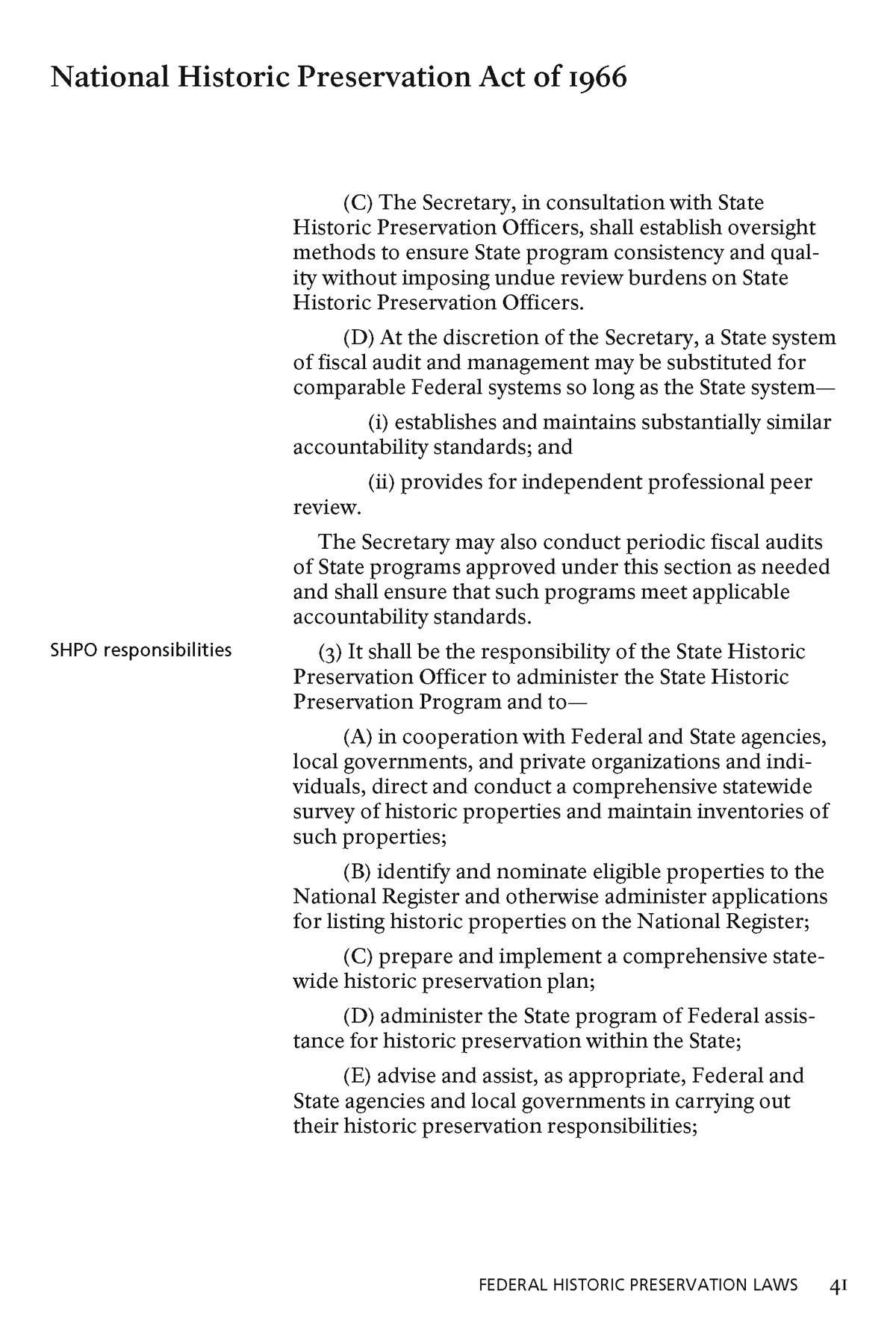

Page 40

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 41

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

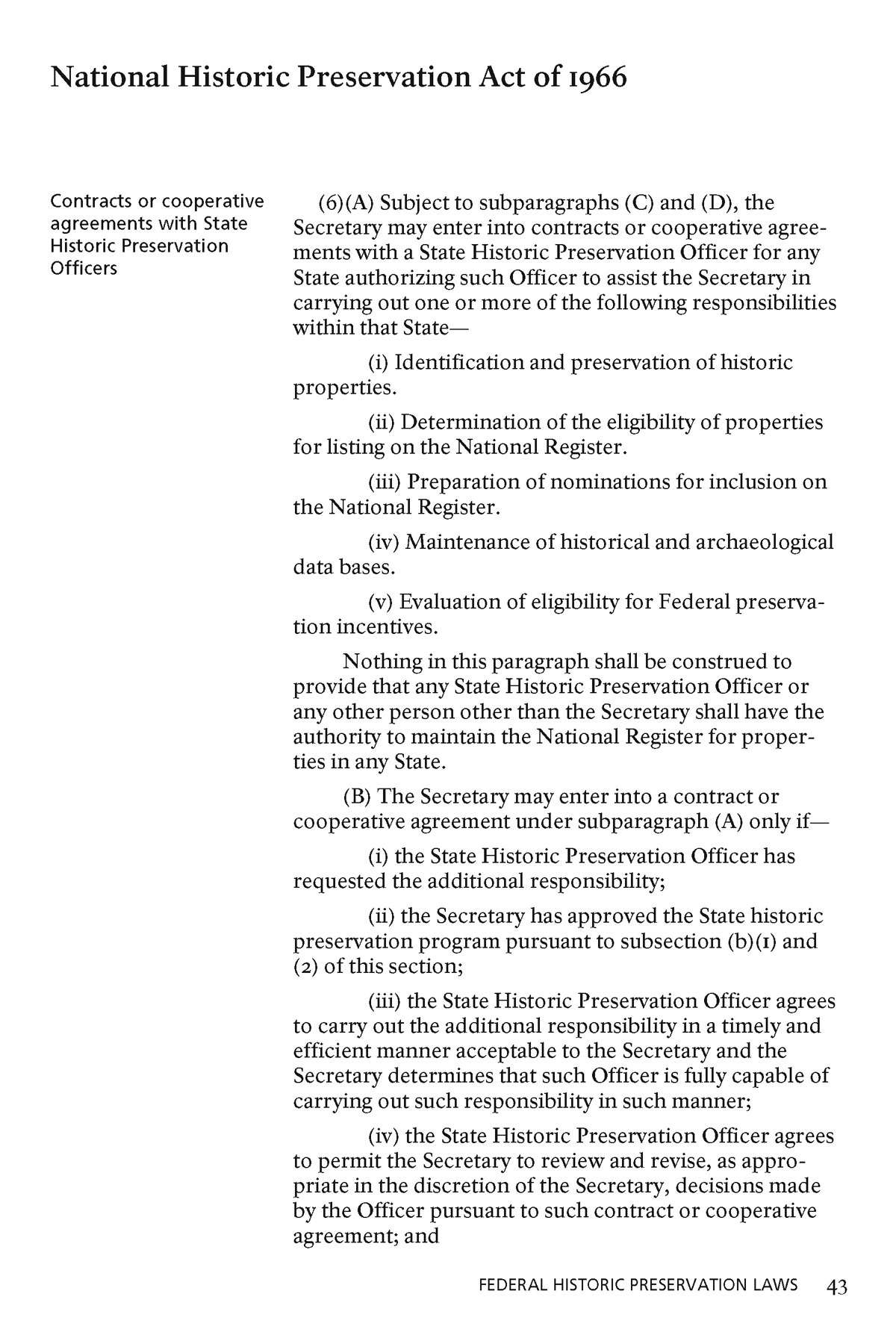

Page 42

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

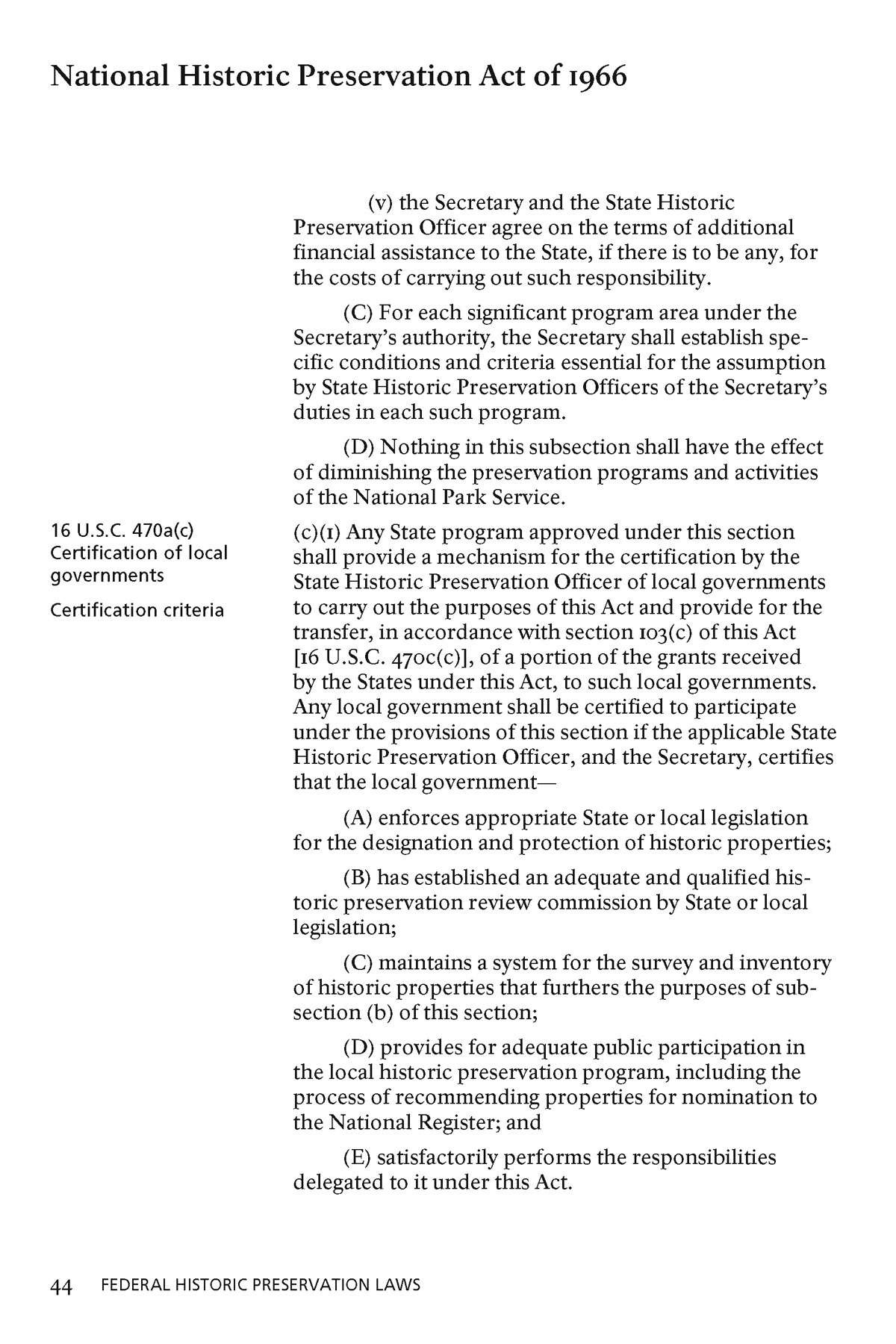

Page 43

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

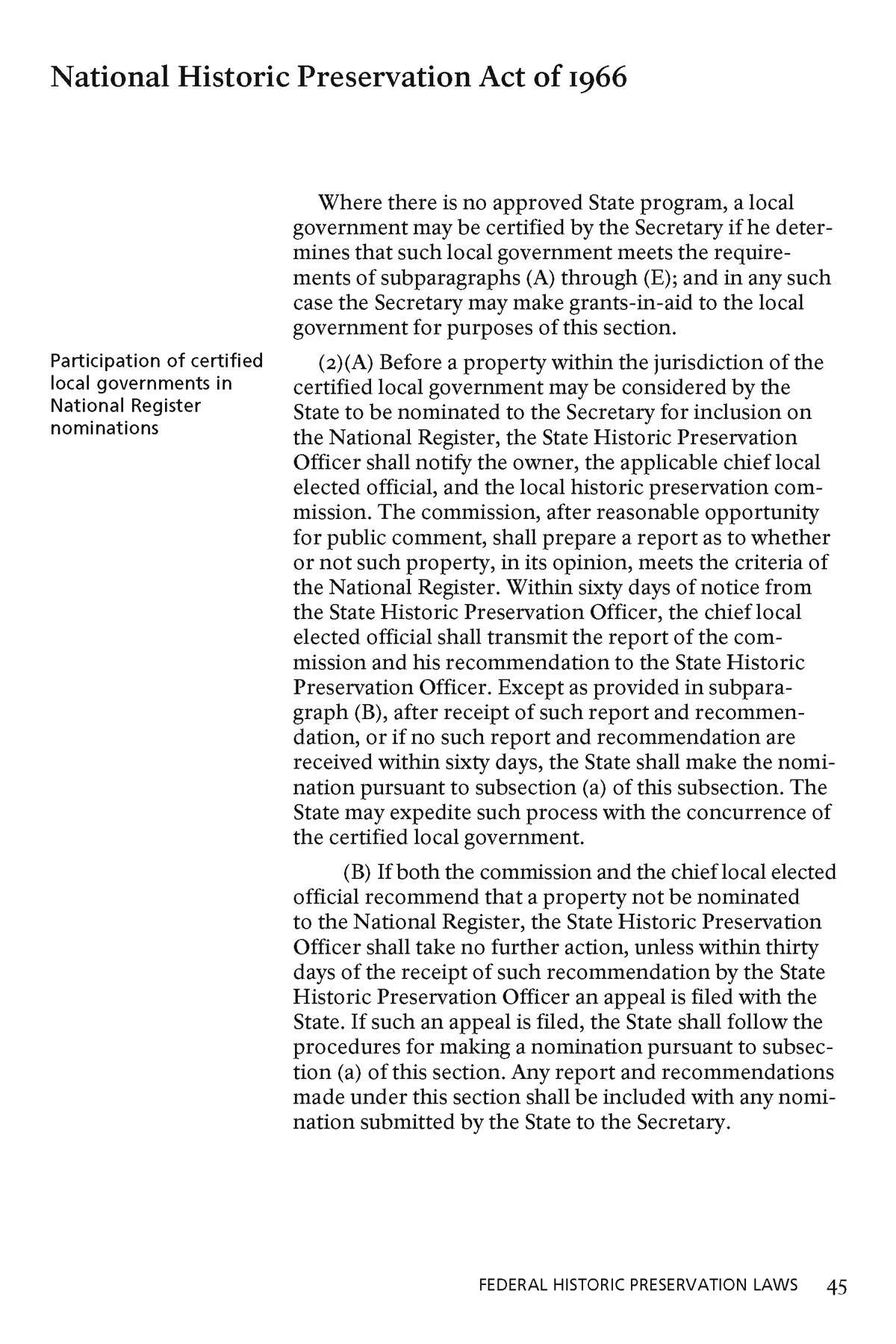

Page 44

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 45

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 46

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 47

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 48

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 49

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 50

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 51

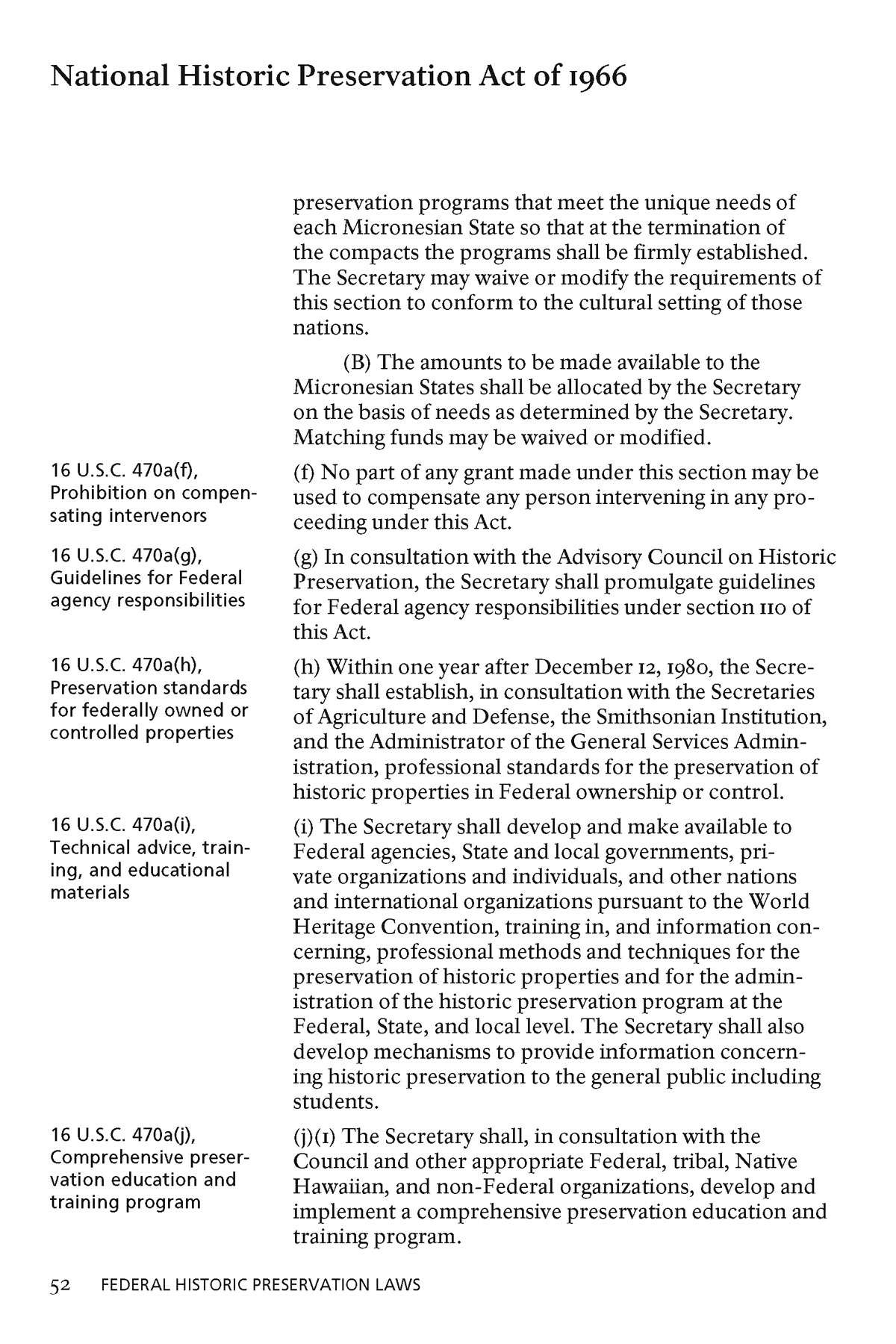

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 52

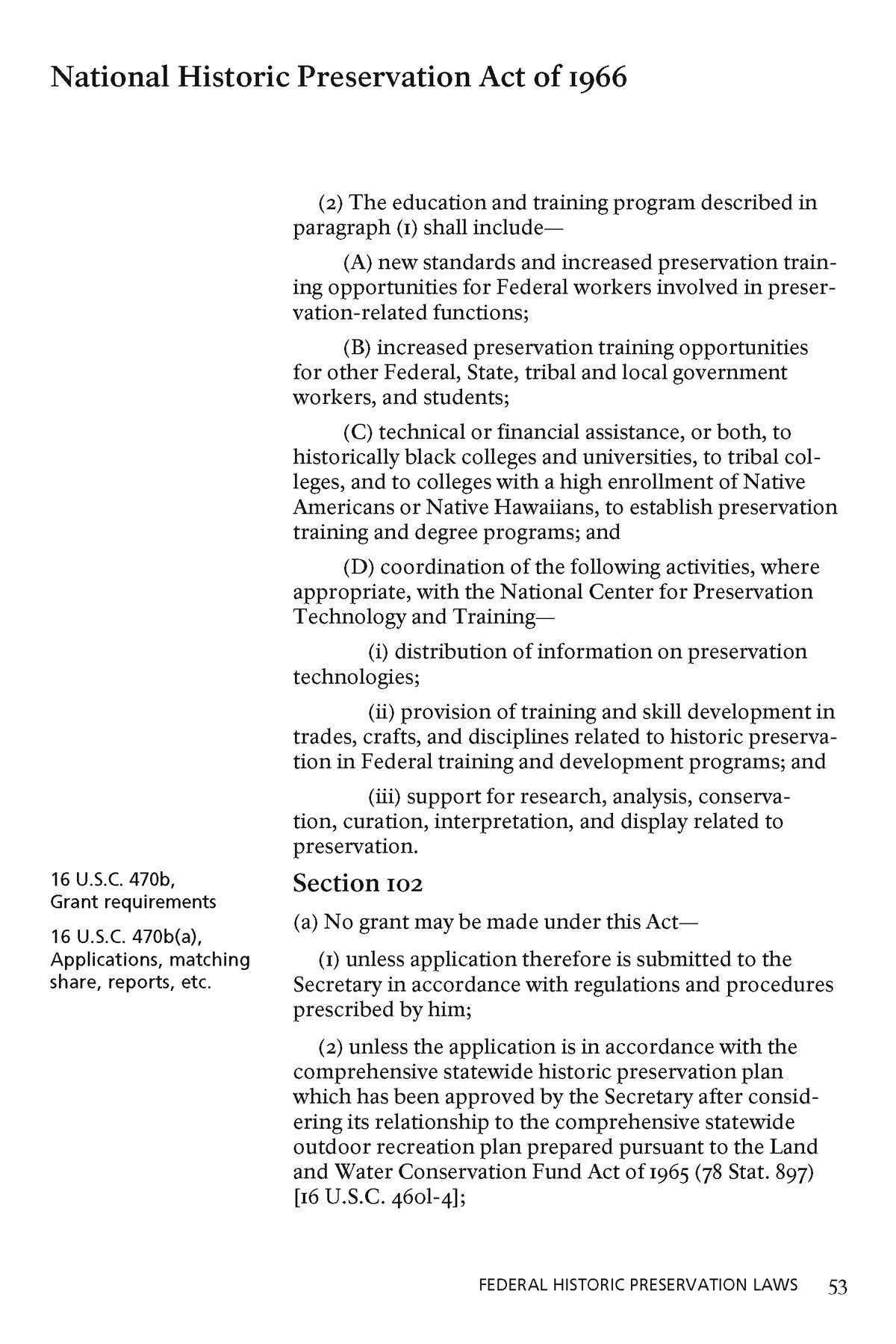

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 53

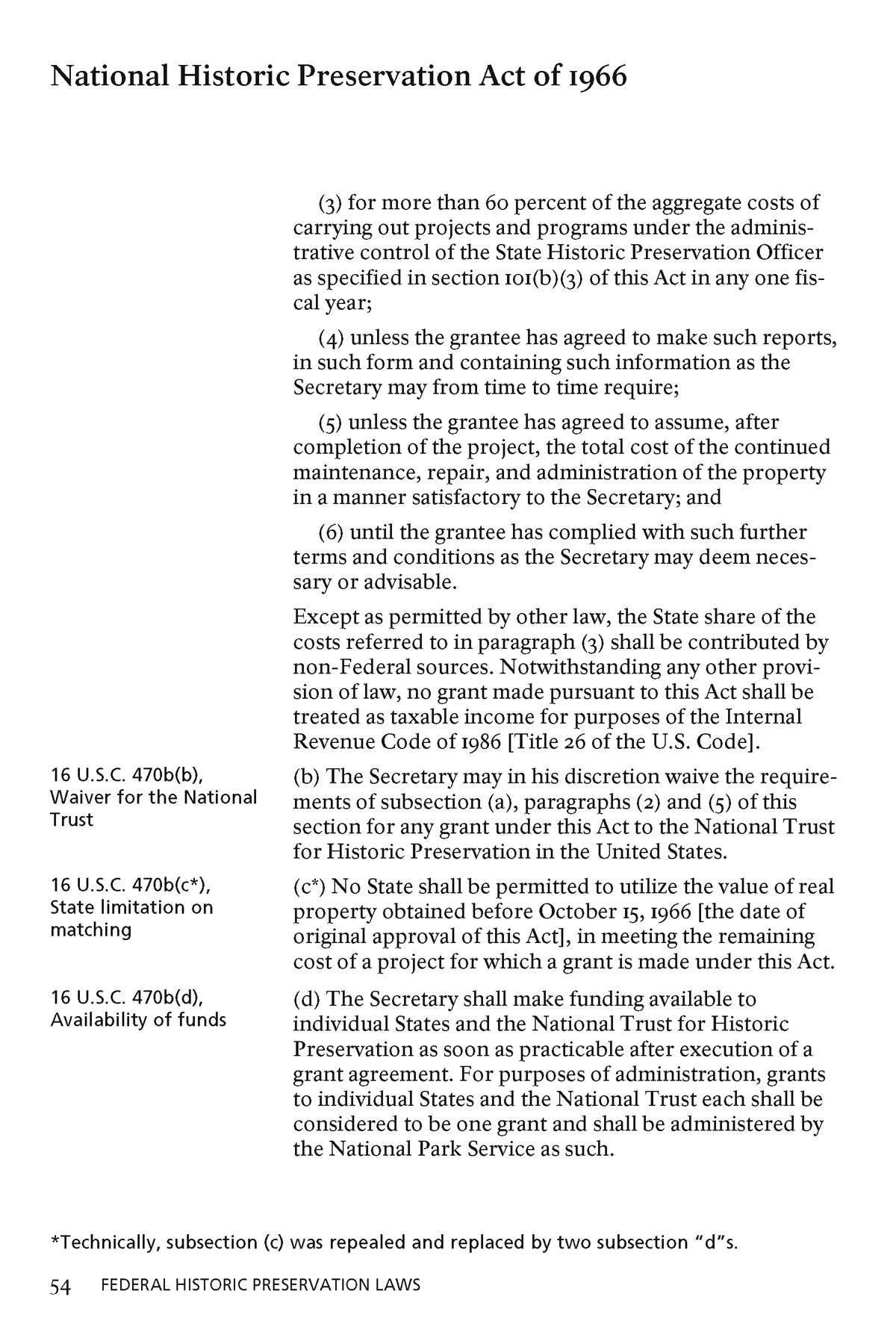

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 54

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 55

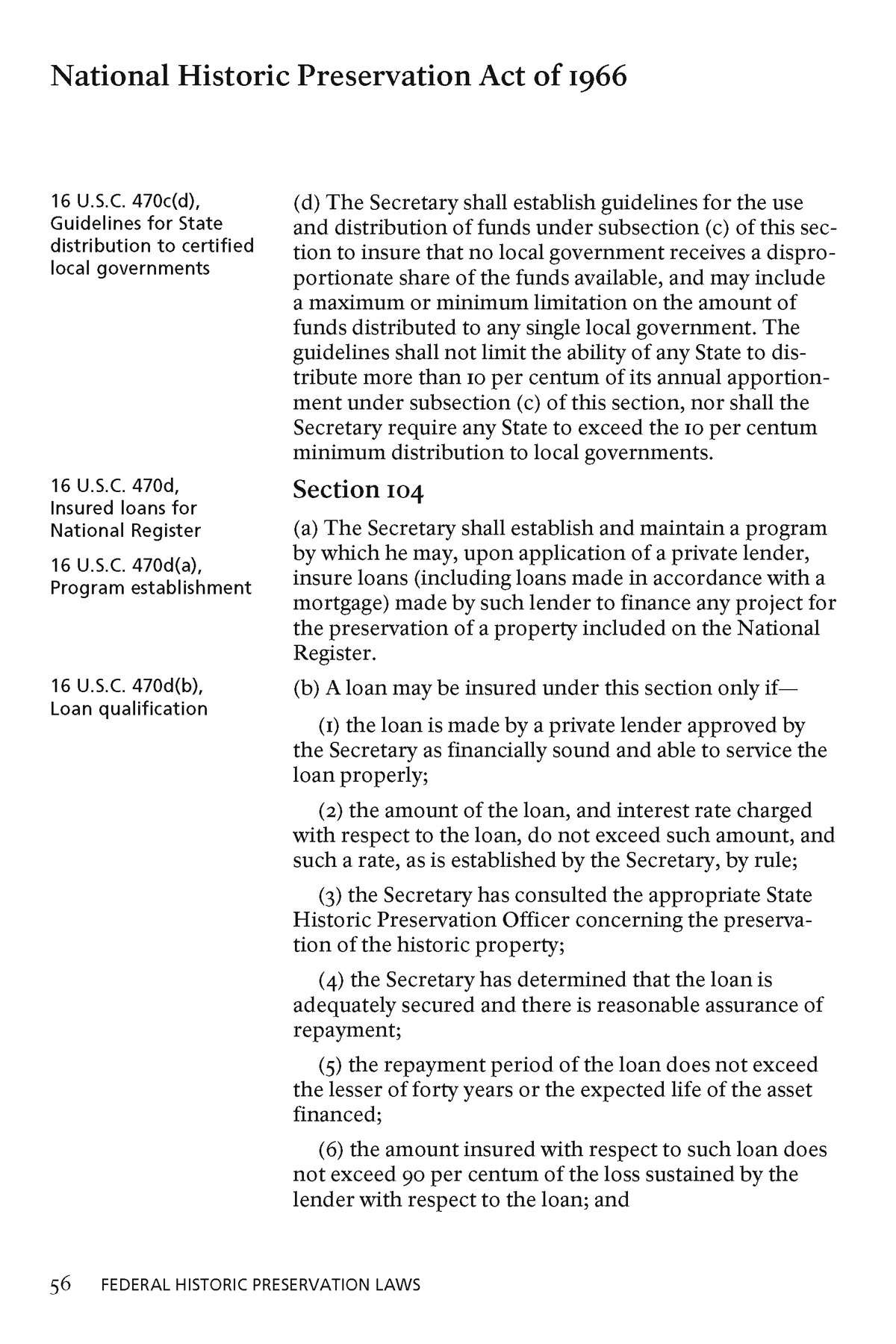

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 56

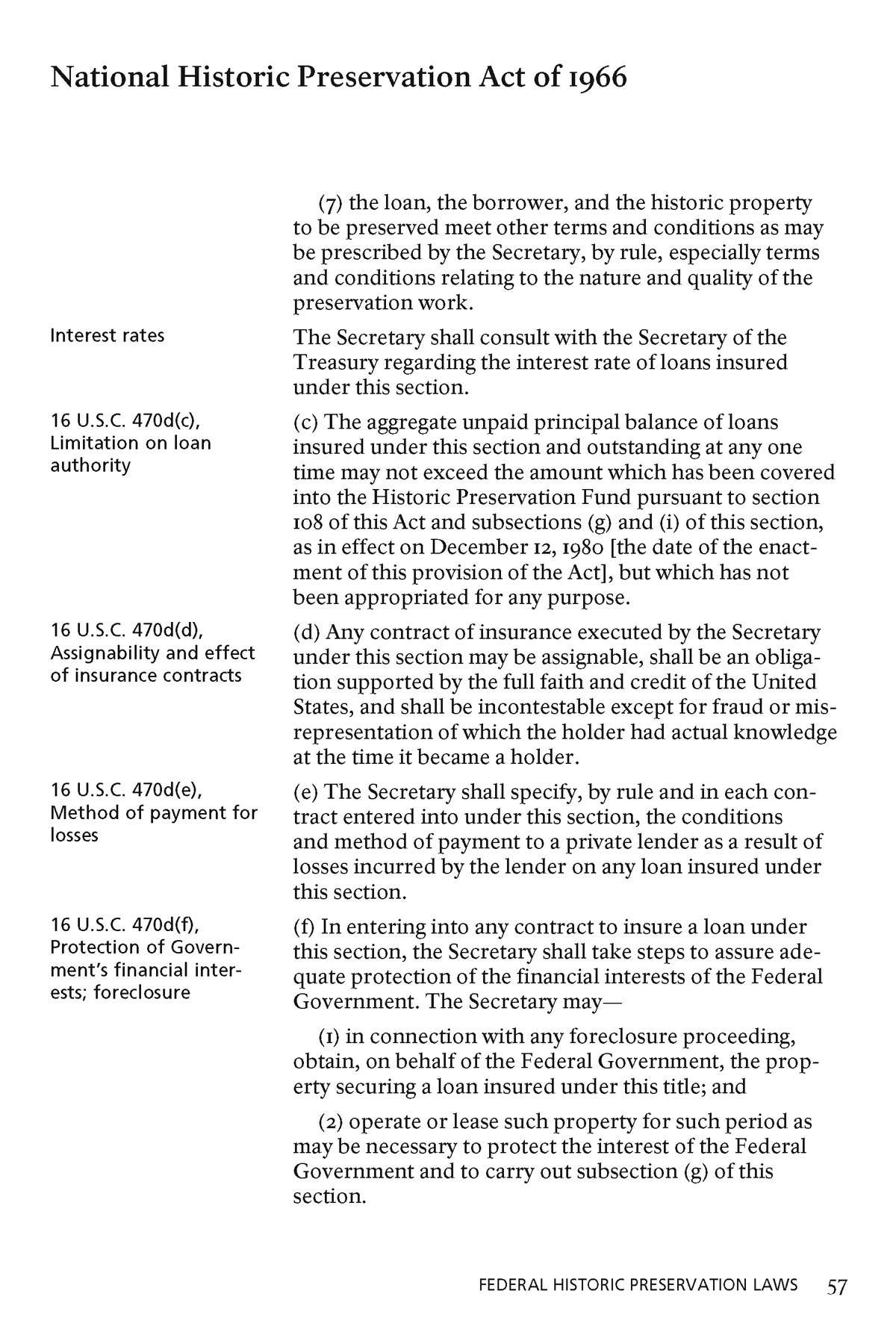

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 57

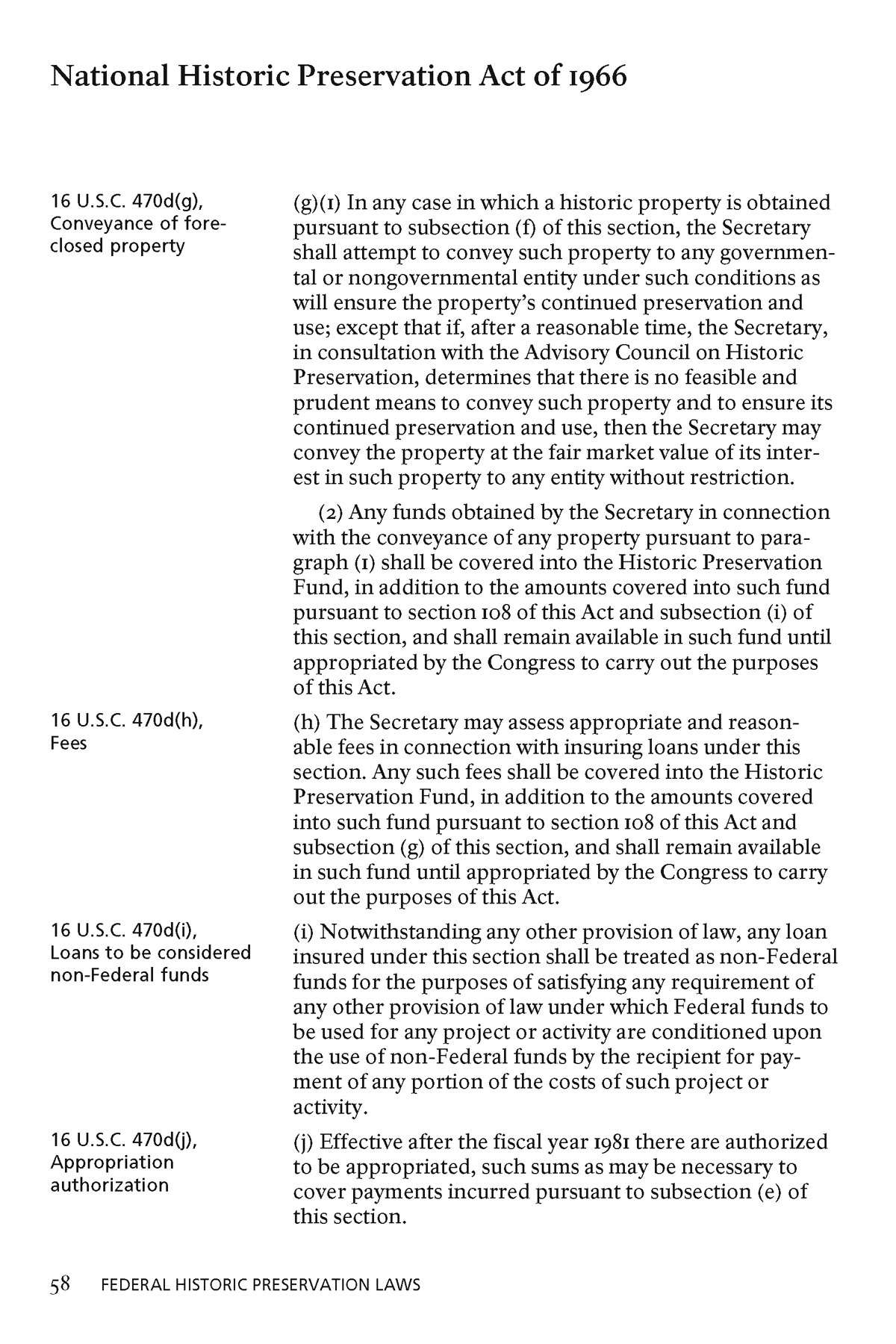

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 58

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 59

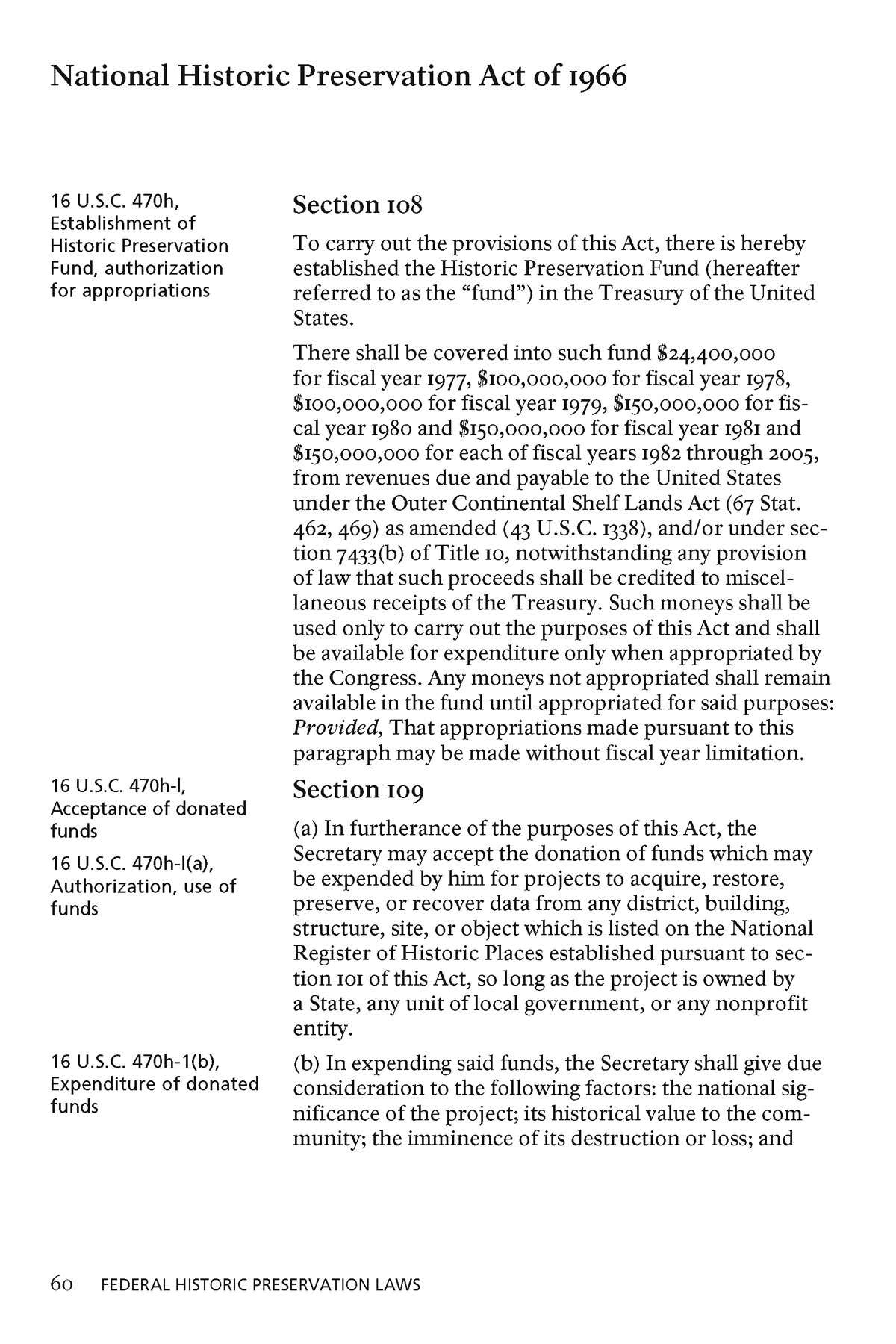

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 60

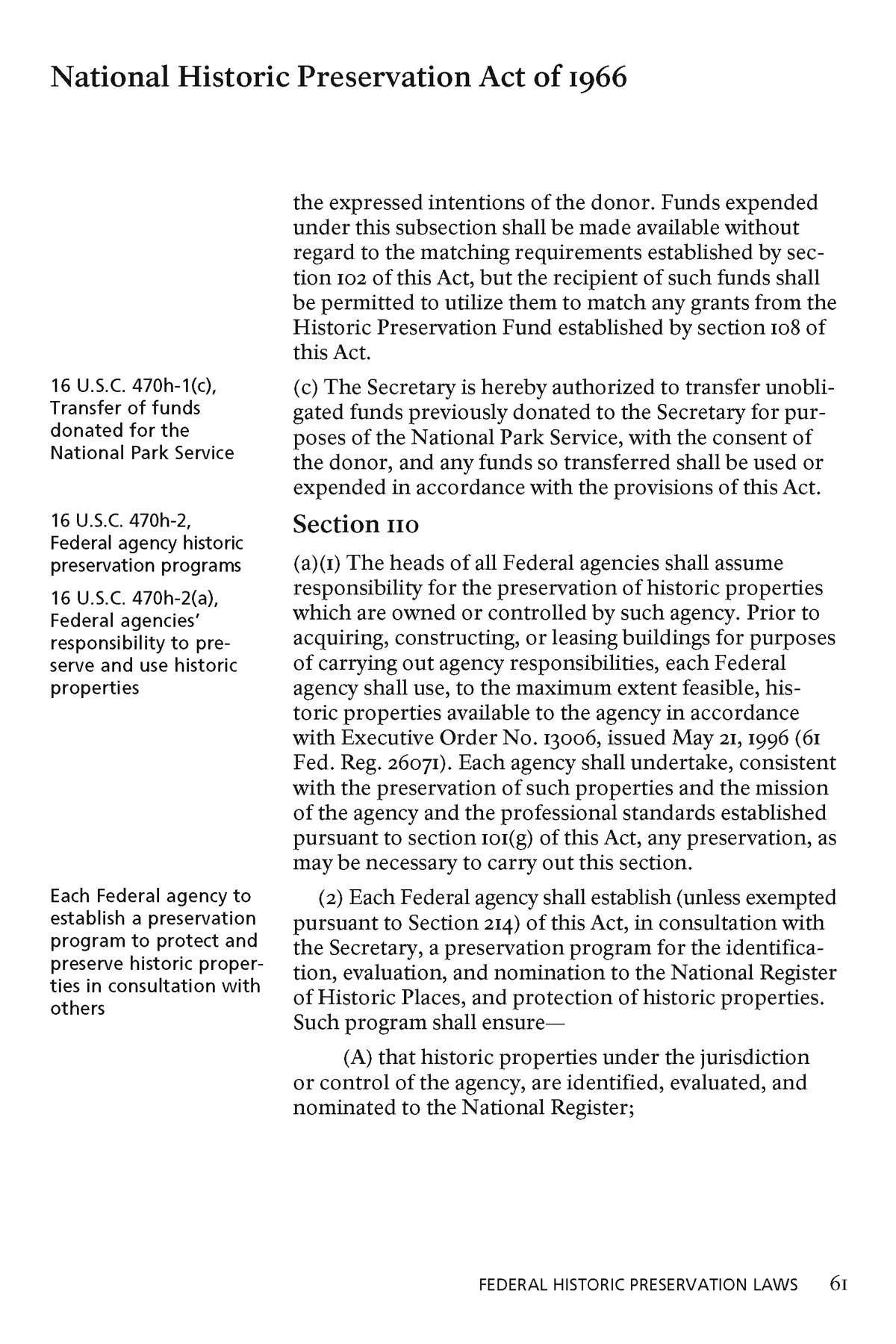

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

Page 61

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

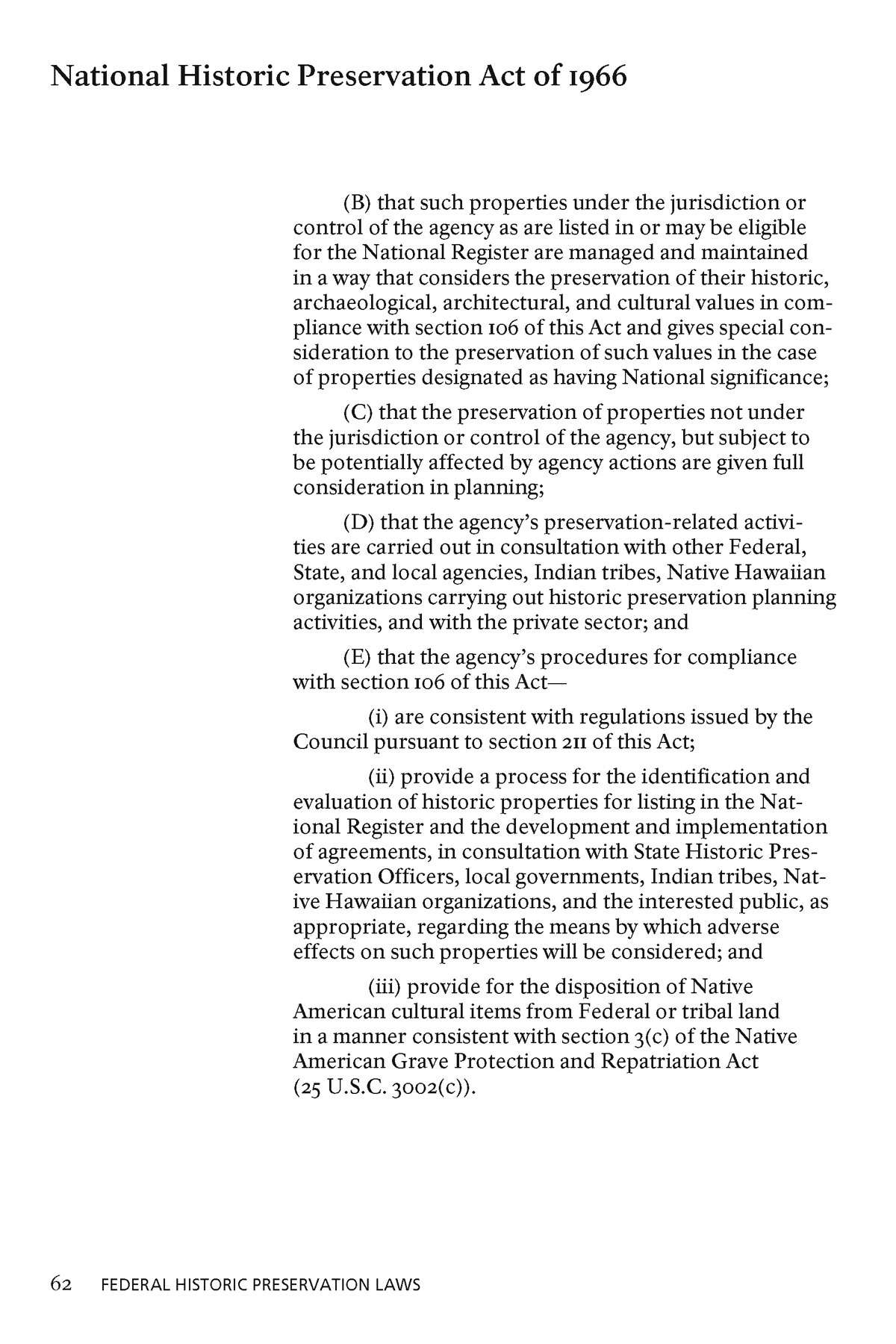

Page 62

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

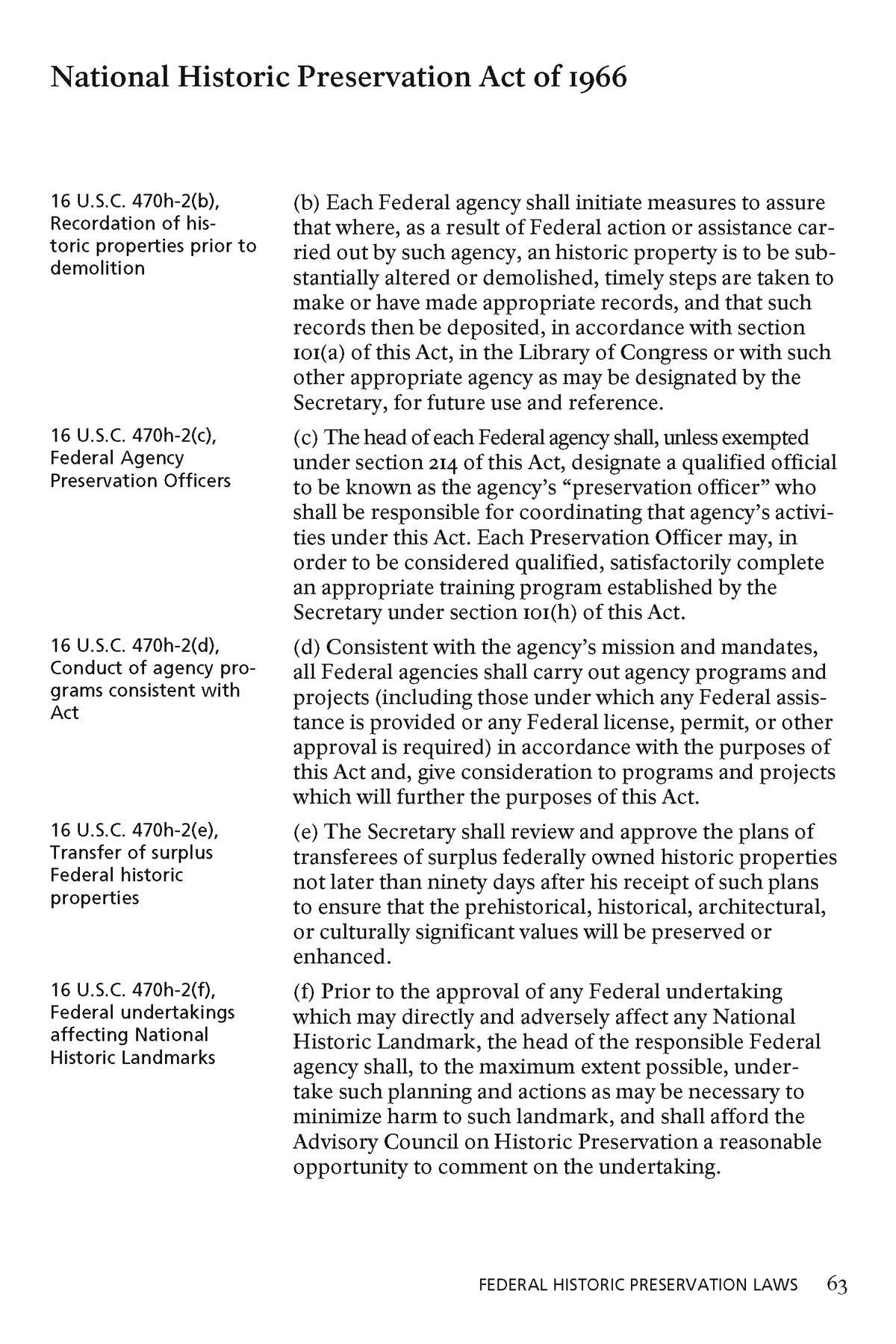

Page 63

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

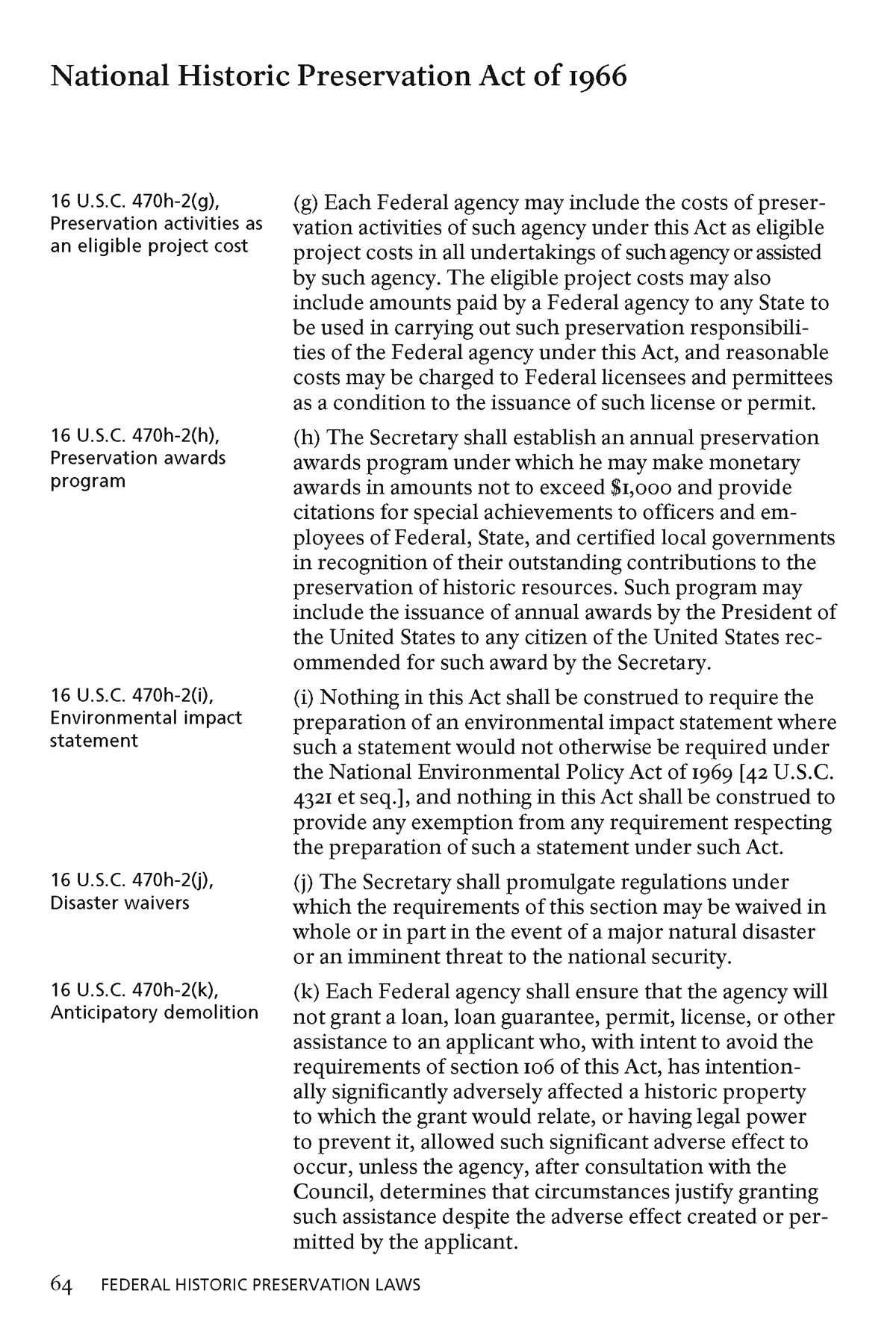

Page 64

National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

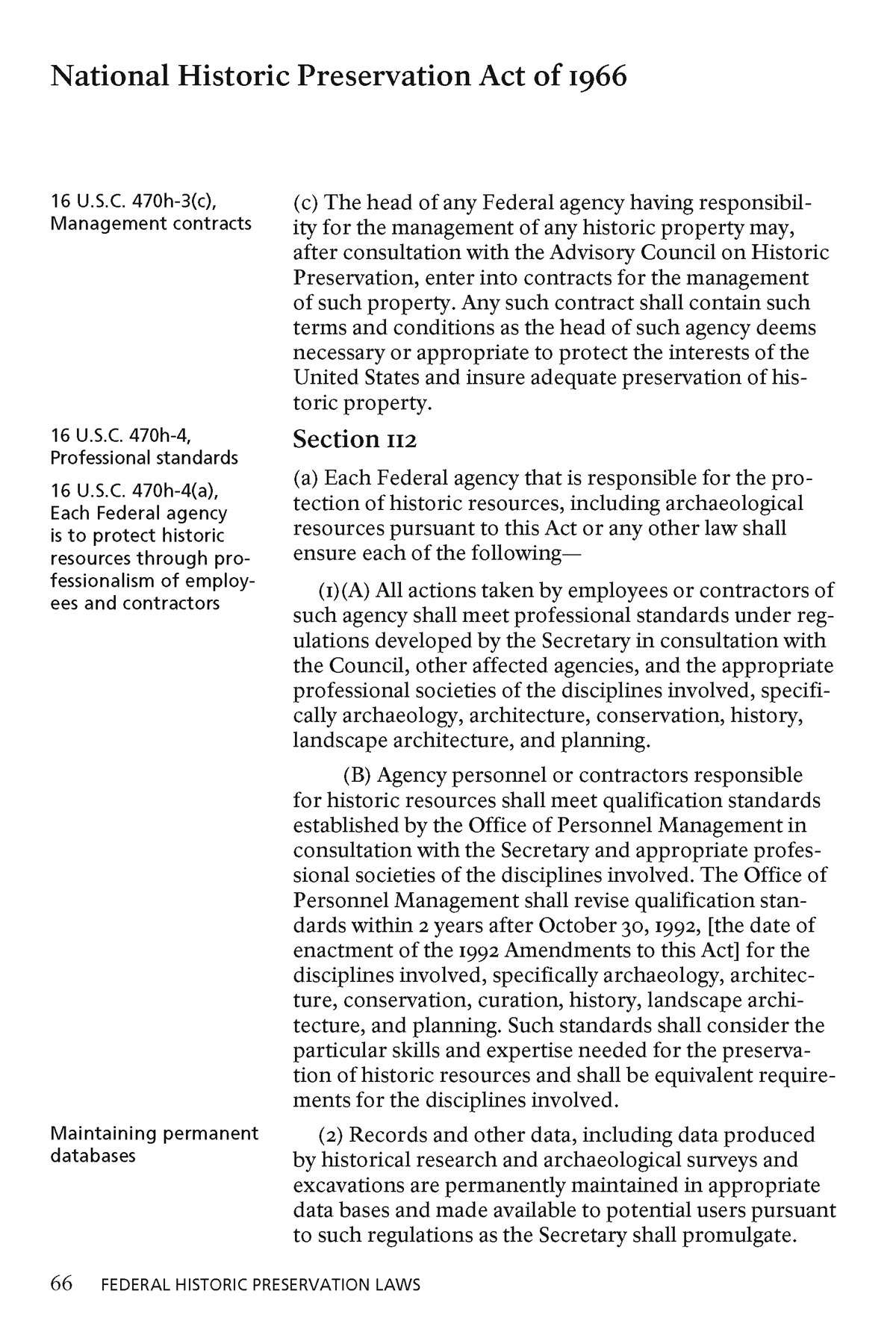

Page 65

Conclusion

Famous American Authors and their Homes

Seeing the Big Picture

After you made all of your matches, you revealed part of the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 – and three of the reasons that Congress passed this law. It says that it's important to preserve the history of the nation because it helps Americans remember who we are.One thing this act did was establish the National Register of Historic Places, which recognizes more than 90,000 historic sites for their significance in American history, architecture, art, archeology, engineering, and culture. When someone wants to register a historic site, they have to submit a long application with extensive information about the significance of the property and the people associated with it. The three houses you saw above are in the National Register of Historic Places.

- Choose one house: "Sunnyside," the home of Washington Irving, the Harriet Beecher Stowe House, or the Mark Twain House. Review the information about it from its application. Write one thing you learned about the American author who lived there.

- What site in your community would you nominate to the National Register of Historic Places? Write two sentences about why the site has historic significance and why it should be preserved.

Your Response

Document

Harriet Beecher Stowe, circa 1870s-80s

ca. 1870s - 1880s

Harriet Beecher Stowe, seen in this image from the 1870s-80s, was an abolitionist, author, and figure in the woman suffrage movement. She wrote more than 20 books and was influential both for her writing and her public stance on social issues of the day.

Her most known work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), was a depiction of life for enslaved people in the mid-19th century. It energized antislavery forces in the North and provoked widespread anger in the South.

After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which punished anyone who offered food or temporary shelter to enslaved people who ran away, and following the loss of her 18-month-old son, Samuel, Stowe was inspired to write about slavery. She used the personal accounts of formerly enslaved people to write her antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life Among the Lowly. When it first appeared in installments in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era between June 5, 1851 and April 1, 1852, it met with hostility by slavery proponents.

Stowe expected that she would write the story in three or four installments, but she eventually wrote more than 40. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was then published as a two-volume book in 1852. It was a best seller in the United States, Britain, and Europe and was translated into over 60 languages.

The book received both high praise and harsh criticism and propelled Stowe and the issue of slavery into the international spotlight. Slavery proponents argued that the novel was nothing more than abolitionist propaganda. In the South, and in the North too, people protested that the depiction of slavery had been melodramatically twisted. Southerners particularly promoted the idea that the institution of slavery was benevolent and benign. Responding to charges that the book was a distortion, Stowe published another book, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which documented the actual cases upon which her book was based to refute critics’ claims that her work was fabricated and based on supposition.

Later, Stowe embraced woman suffrage and briefly considered an alliance with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who tried in 1869 to recruit her to write for their newspaper, The Revolution. Stowe declined the partnership, but eventually developed a deeper empathy for the women’s rights movement and the activities of the suffragists. She wrote a series for the Atlantic, and in one installment, she wrote, “The question of Woman and her Sphere is now, perhaps, the greatest of the age....If the principles on which we founded our government are true, that taxation must not exist without representation, and if women hold property and are taxed, it follows that women should be represented in the State by their votes, or there is an illogical working of our government.”

Throughout her life, Stowe used literature to shape public opinion and leaned on her own experiences as a woman and a mother. She was keenly aware of racial differences and regional customs, and it translated into her distinct influence on the American experience. Writing at a time when women were denied the vote and had no representation in Congress, Stowe used literature as her political voice.

Her most known work, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1852), was a depiction of life for enslaved people in the mid-19th century. It energized antislavery forces in the North and provoked widespread anger in the South.

After Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, which punished anyone who offered food or temporary shelter to enslaved people who ran away, and following the loss of her 18-month-old son, Samuel, Stowe was inspired to write about slavery. She used the personal accounts of formerly enslaved people to write her antislavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin: or, Life Among the Lowly. When it first appeared in installments in the abolitionist newspaper The National Era between June 5, 1851 and April 1, 1852, it met with hostility by slavery proponents.

Stowe expected that she would write the story in three or four installments, but she eventually wrote more than 40. The novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was then published as a two-volume book in 1852. It was a best seller in the United States, Britain, and Europe and was translated into over 60 languages.

The book received both high praise and harsh criticism and propelled Stowe and the issue of slavery into the international spotlight. Slavery proponents argued that the novel was nothing more than abolitionist propaganda. In the South, and in the North too, people protested that the depiction of slavery had been melodramatically twisted. Southerners particularly promoted the idea that the institution of slavery was benevolent and benign. Responding to charges that the book was a distortion, Stowe published another book, A Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which documented the actual cases upon which her book was based to refute critics’ claims that her work was fabricated and based on supposition.

Later, Stowe embraced woman suffrage and briefly considered an alliance with Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, who tried in 1869 to recruit her to write for their newspaper, The Revolution. Stowe declined the partnership, but eventually developed a deeper empathy for the women’s rights movement and the activities of the suffragists. She wrote a series for the Atlantic, and in one installment, she wrote, “The question of Woman and her Sphere is now, perhaps, the greatest of the age....If the principles on which we founded our government are true, that taxation must not exist without representation, and if women hold property and are taxed, it follows that women should be represented in the State by their votes, or there is an illogical working of our government.”

Throughout her life, Stowe used literature to shape public opinion and leaned on her own experiences as a woman and a mother. She was keenly aware of racial differences and regional customs, and it translated into her distinct influence on the American experience. Writing at a time when women were denied the vote and had no representation in Congress, Stowe used literature as her political voice.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of War Information.

National Archives Identifier: 535784

Full Citation: Photograph 208-N-25004; Harriet Beecher Stowe, circa 1870s-80s; ca. 1870s - 1880s; Photographs of Allied and Axis Personalities and Activities, 1942 - 1945; Records of the Office of War Information, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/harriet-beecher-stowe, April 24, 2024]Harriet Beecher Stowe, circa 1870s-80s

Page 1

Document

Connecticut SP Stowe, Harriet Beecher, House

1970

The Harriet Beecher Stowe House was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970. This photograph and the following descriptions were included with its nomination form.

Architecturally, the Stowe House is a fine example of the Gothic cottage. The unknown designer of the Stowe House, built in 1871, showed the Victorian attention to decorative motifs and skill in creating a distinctive design. He employed a subtle combination of elements of the rustic cottage with the Gothic villa, translated into brick.

Historically, the Stowe House was part of a remarkable neighborhood known as Hook Farm. On the western edge of Hartford, Connecticut, a wide meander of the Park River once embraced a heavily wooded tract long known as The Nook. In this area there developed a neighborhood of interrelated families and friends, whose wide range of interests and accomplishments made Nook Farm a cultural center and a mecca for distinguished visitors during the second half of the 19th century.

Its two foremost residents, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811 - 1896) and Samuel L. Clemens (1835 - 1910), attained international fame. Mrs. Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin reached the emotions of the nation and helped change its attitude about slavery and the course of our country’s portrayals of New England character and village life. The public continues to relish the keenness of Mark Twain’s wit and his rare insight into the weaknesses and inconsistencies of mankind.

Restoration of the Stowe House was made possible by the foresight and generosity of the late Miss Katharine Seymour Day, a grand-niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Miss Day lived in the Stowe House from 1927 until her death in 1964. In 1941 Miss Day established the Stowe-Day Memorial Library and Historical Foundation to which she bequeathed her entire estate.

Architecturally, the Stowe House is a fine example of the Gothic cottage. The unknown designer of the Stowe House, built in 1871, showed the Victorian attention to decorative motifs and skill in creating a distinctive design. He employed a subtle combination of elements of the rustic cottage with the Gothic villa, translated into brick.

Historically, the Stowe House was part of a remarkable neighborhood known as Hook Farm. On the western edge of Hartford, Connecticut, a wide meander of the Park River once embraced a heavily wooded tract long known as The Nook. In this area there developed a neighborhood of interrelated families and friends, whose wide range of interests and accomplishments made Nook Farm a cultural center and a mecca for distinguished visitors during the second half of the 19th century.

Its two foremost residents, Harriet Beecher Stowe (1811 - 1896) and Samuel L. Clemens (1835 - 1910), attained international fame. Mrs. Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin reached the emotions of the nation and helped change its attitude about slavery and the course of our country’s portrayals of New England character and village life. The public continues to relish the keenness of Mark Twain’s wit and his rare insight into the weaknesses and inconsistencies of mankind.

Restoration of the Stowe House was made possible by the foresight and generosity of the late Miss Katharine Seymour Day, a grand-niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe. Miss Day lived in the Stowe House from 1927 until her death in 1964. In 1941 Miss Day established the Stowe-Day Memorial Library and Historical Foundation to which she bequeathed her entire estate.

This primary source comes from the Records of the National Park Service.

National Archives Identifier: 132354643

Full Citation: Connecticut SP Stowe, Harriet Beecher, House; 1970; National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: Connecticut; National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013 - 2017; Records of the National Park Service, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/harriet-beecher-stowe-house, April 24, 2024]Connecticut SP Stowe, Harriet Beecher, House

Page 1

Document

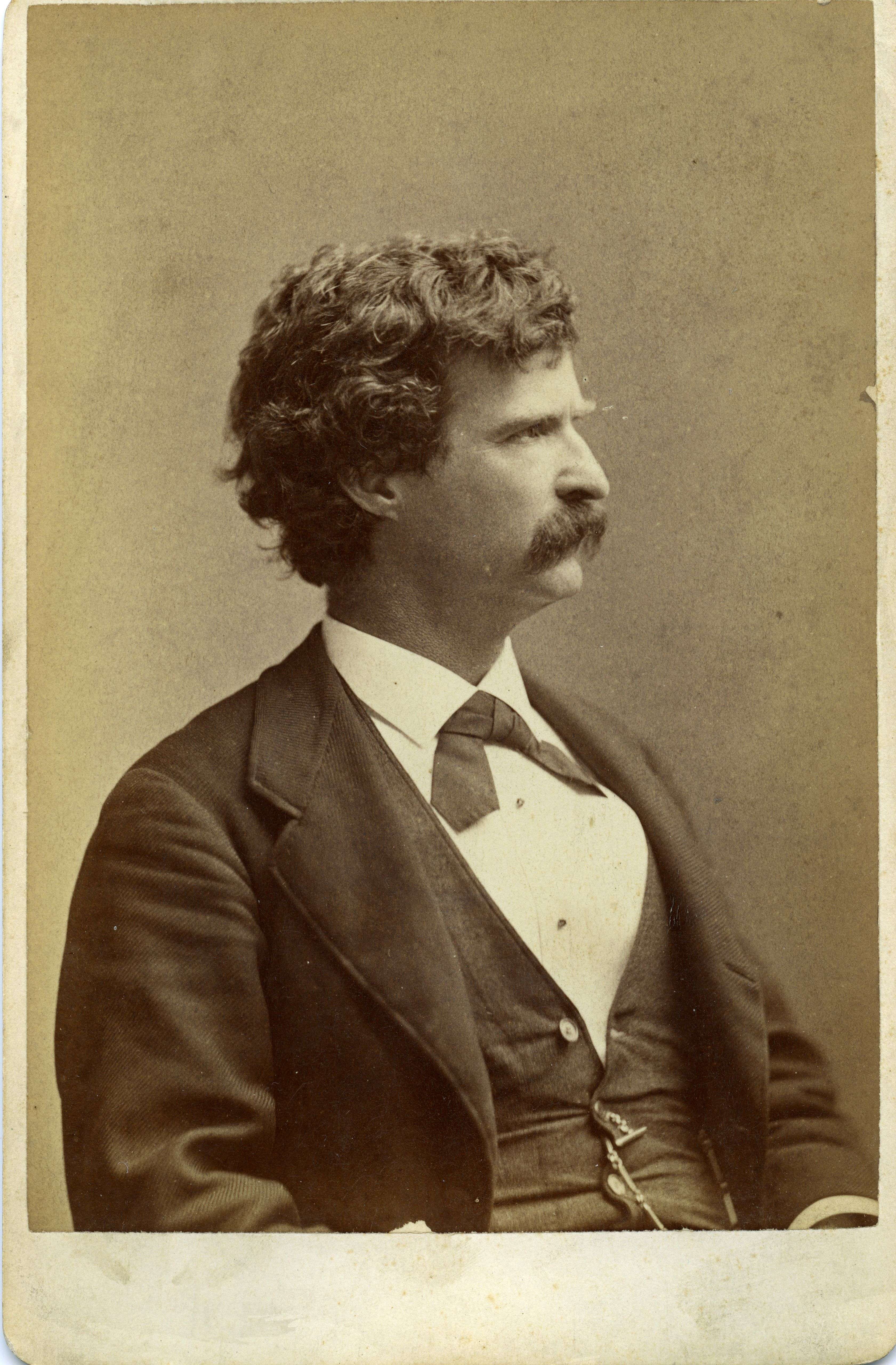

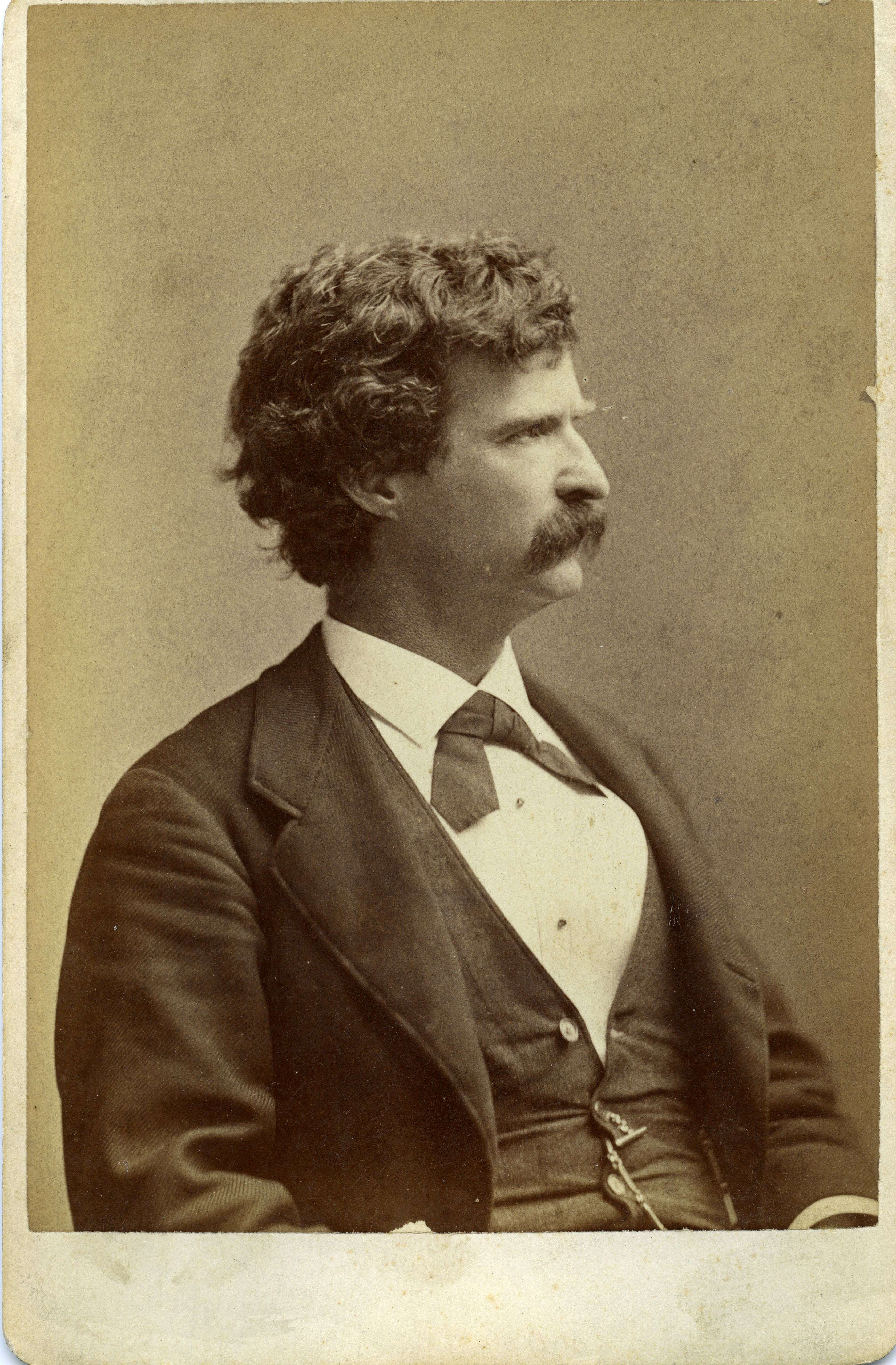

Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens)

ca. 1862 - 1884

This primary source comes from the Collection FL: Frank W. Legg Photographic Collection of Portraits of Nineteenth-Century Notables.

National Archives Identifier: 82586130

Full Citation: Photograph FL-FL-6; Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens); ca. 1862 - 1884; Series: Portraits, 1862 - 1884; Collection FL: Frank W. Legg Photographic Collection of Portraits of Nineteenth-Century Notables, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/mark-twain, April 24, 2024]Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens)

Page 1

Document

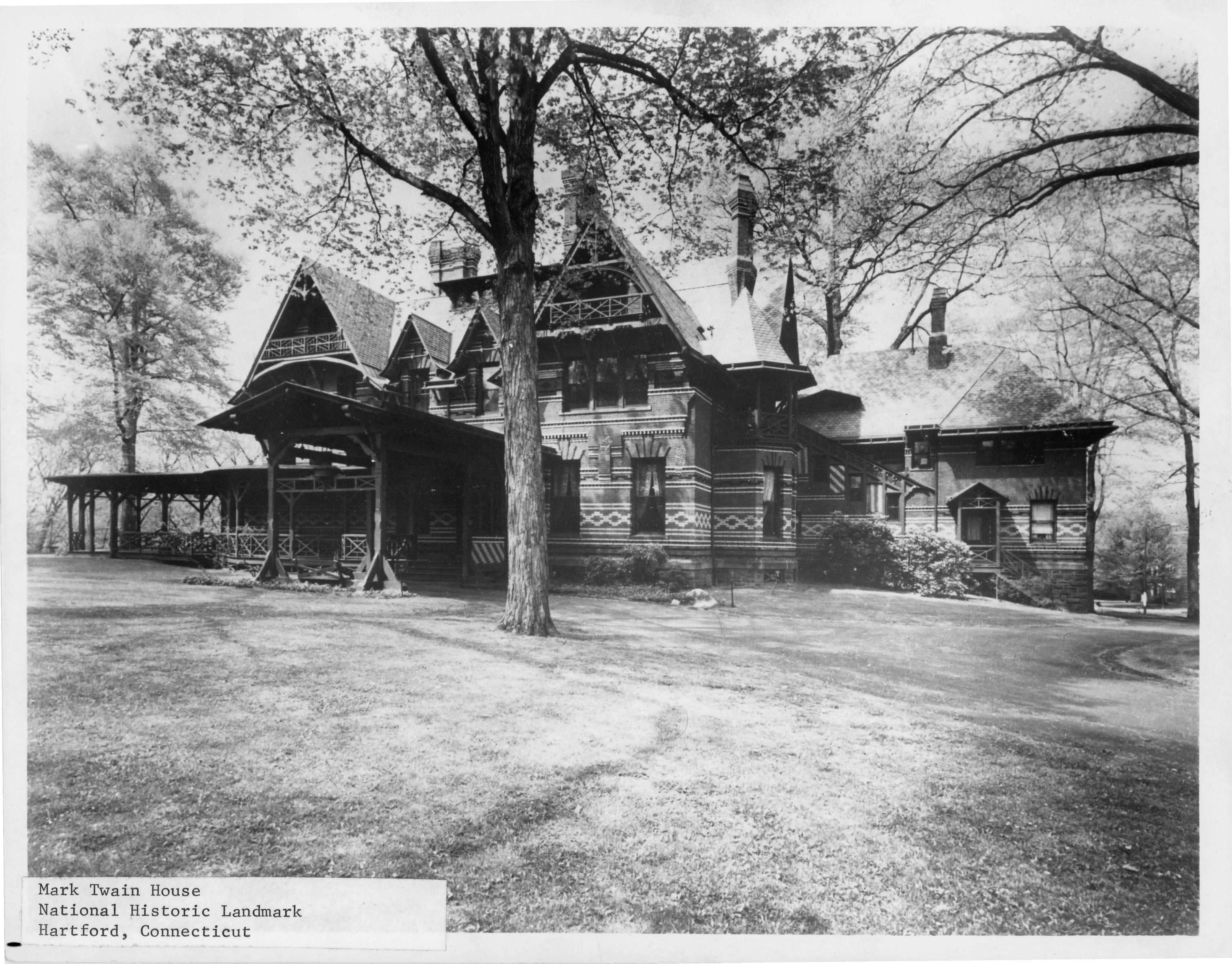

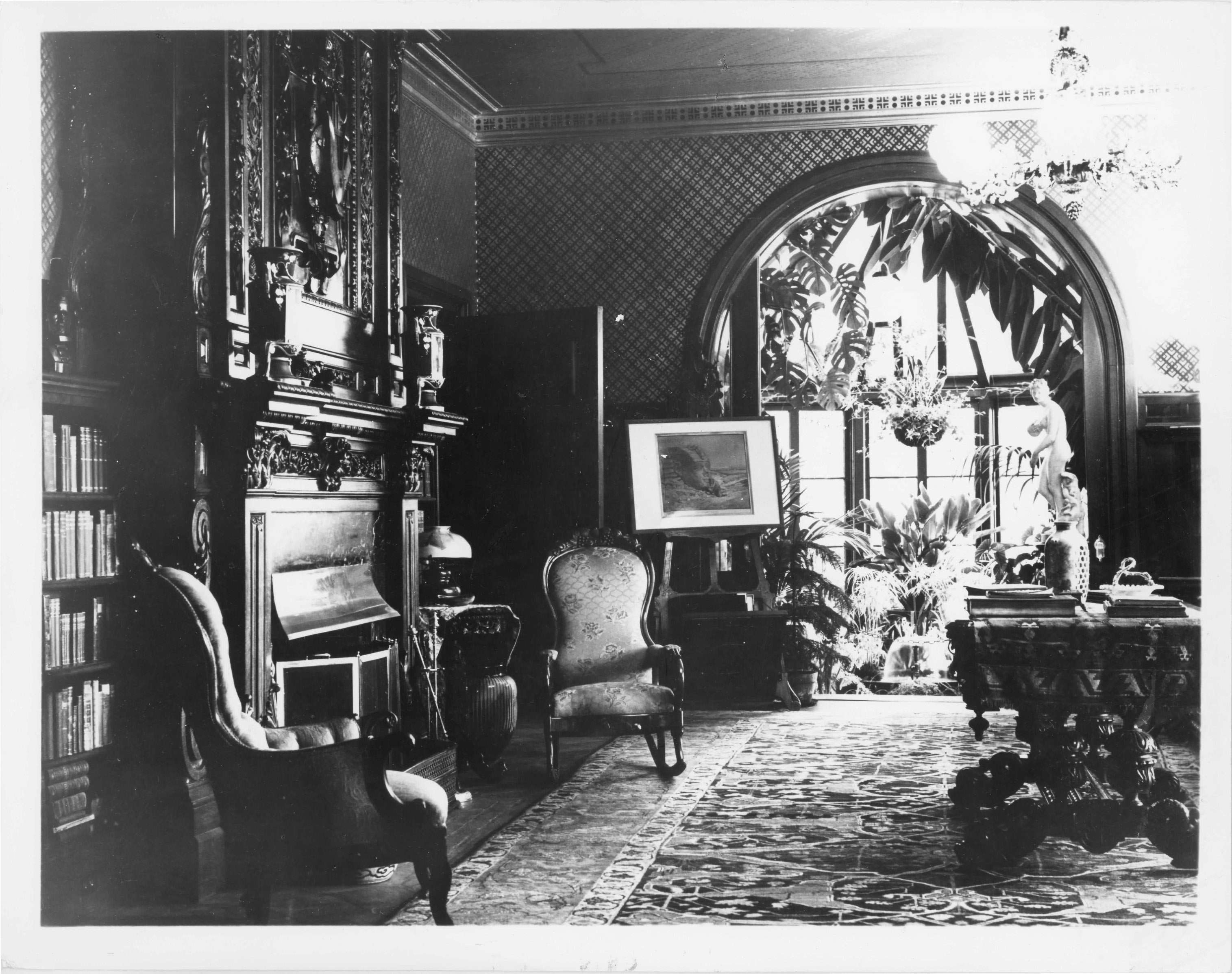

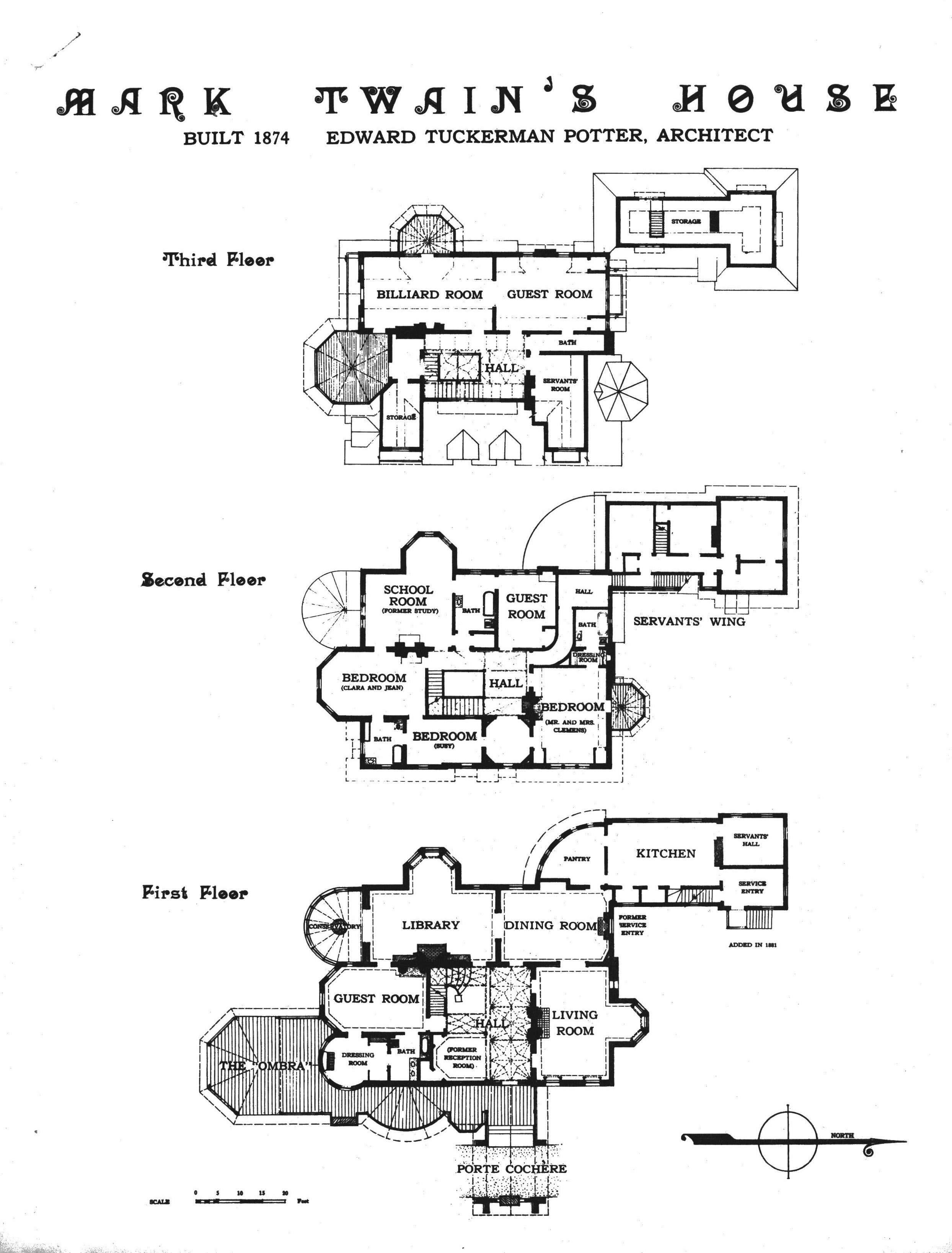

Connecticut NHL Twain, Mark, Home

1874 (photograph ca. 1975)

This was the home of Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) from 1874, when it was completed, until financial disaster forced Twain to move his family to Europe in 1891. Located in Hartford, Connecticut, it remained his property until 1903 and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1963. These images and the following descriptions were included with the nomination to add it to the National Register of Historic Places.

In his book Mr. Clemens. and Mark Twain, author Justin Kaplan described the structure as: "The house was permanent polychrome and gingerbread Gothic; it was part steamboat, part medieval stronghold, and part cuckoo clock... It was the conspicuous symbol of his success as a writer, lecturer, and dramatist."

Clemens wanted a radical departure from the typical box-like Hartford houses of the period, and Edward Tuckerman Potter, an architect active in the Hartford area, designed for him this asymmetrical polychromatic brick structure, with sweeping ilrood cornices and gables and flamboyant patterns of black and vermilion brick.

Because of the well-known characters Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, Clemens is most readily identified with Hannibal and the Midwest. Ironically, however, he did not write in Missouri. It was during the 17 years he lived in this house he commissioned at 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Connecticut, that numerous books, sketches and articles were written including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Prince and the Pauper, Life on the Mississippi, A Tramp Abroad, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.

Samuel Clemens first came to Hartford in 1868 to discuss the publishing of Innocents Abroad with Elisha Bliss, president of the American Publishing Company. Clemens liked Hartford from the time of that visit and shortly afterward wrote, "Of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see this is the chief." In 1870 he married Olivia Langdon of Elmira, N.Y., and in 1871 he left his job on the Buffalo, N.Y. Express and moved to Hartford, attracted by its location, industry, and list of literary and social personalities.

Because his publisher, Bliss, and many literary friends lived there, the Clemenses decided in 1873 to make Hartford their permanent residence. With the proceeds from the publication of Innocents Abroad they bought land and commissioned Edward Tuckerman Potter to design their house. The Clemens chose for their home the Nook Farm area, a small, closely knit, influential community where the neighbors, among them Harriet Beecher Stowe and Charles Dudley Warner, and their many guests met for dinner parties and teas, charades, and weekly stag billiard sessions. The elderly Mrs. Stowe often wandered into the Clemenses' home to play their piano. She designed their conservatory with its dripping fountain, similar to ones she designed for other Nook Farm houses.

The house was completed in September 1874 and Mr. and Mrs. Clemens and daughters Susy, born in 1872, and Clara, born in 1874, moved in. The third daughter Jean, was born in 1880. The house represents Samuel L. Clemens, successful author and family man. This house saw his rise to the peak of his creative powers and his tragic financial failure.

In his book Mr. Clemens. and Mark Twain, author Justin Kaplan described the structure as: "The house was permanent polychrome and gingerbread Gothic; it was part steamboat, part medieval stronghold, and part cuckoo clock... It was the conspicuous symbol of his success as a writer, lecturer, and dramatist."

Clemens wanted a radical departure from the typical box-like Hartford houses of the period, and Edward Tuckerman Potter, an architect active in the Hartford area, designed for him this asymmetrical polychromatic brick structure, with sweeping ilrood cornices and gables and flamboyant patterns of black and vermilion brick.

Because of the well-known characters Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn, Clemens is most readily identified with Hannibal and the Midwest. Ironically, however, he did not write in Missouri. It was during the 17 years he lived in this house he commissioned at 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Connecticut, that numerous books, sketches and articles were written including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Prince and the Pauper, Life on the Mississippi, A Tramp Abroad, and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court.

Samuel Clemens first came to Hartford in 1868 to discuss the publishing of Innocents Abroad with Elisha Bliss, president of the American Publishing Company. Clemens liked Hartford from the time of that visit and shortly afterward wrote, "Of all the beautiful towns it has been my fortune to see this is the chief." In 1870 he married Olivia Langdon of Elmira, N.Y., and in 1871 he left his job on the Buffalo, N.Y. Express and moved to Hartford, attracted by its location, industry, and list of literary and social personalities.

Because his publisher, Bliss, and many literary friends lived there, the Clemenses decided in 1873 to make Hartford their permanent residence. With the proceeds from the publication of Innocents Abroad they bought land and commissioned Edward Tuckerman Potter to design their house. The Clemens chose for their home the Nook Farm area, a small, closely knit, influential community where the neighbors, among them Harriet Beecher Stowe and Charles Dudley Warner, and their many guests met for dinner parties and teas, charades, and weekly stag billiard sessions. The elderly Mrs. Stowe often wandered into the Clemenses' home to play their piano. She designed their conservatory with its dripping fountain, similar to ones she designed for other Nook Farm houses.

The house was completed in September 1874 and Mr. and Mrs. Clemens and daughters Susy, born in 1872, and Clara, born in 1874, moved in. The third daughter Jean, was born in 1880. The house represents Samuel L. Clemens, successful author and family man. This house saw his rise to the peak of his creative powers and his tragic financial failure.

This primary source comes from the Records of the National Park Service.

National Archives Identifier: 132353640

Full Citation: Connecticut NHL Twain, Mark, Home; 1874 (photograph ca. 1975); National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: Connecticut; National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013 - 2017; Records of the National Park Service, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/twain-house, April 24, 2024]Connecticut NHL Twain, Mark, Home

Page 1

Connecticut NHL Twain, Mark, Home

Page 2

Connecticut NHL Twain, Mark, Home

Page 3

Connecticut NHL Twain, Mark, Home

Page 4

Connecticut NHL Twain, Mark, Home

Page 5

Document

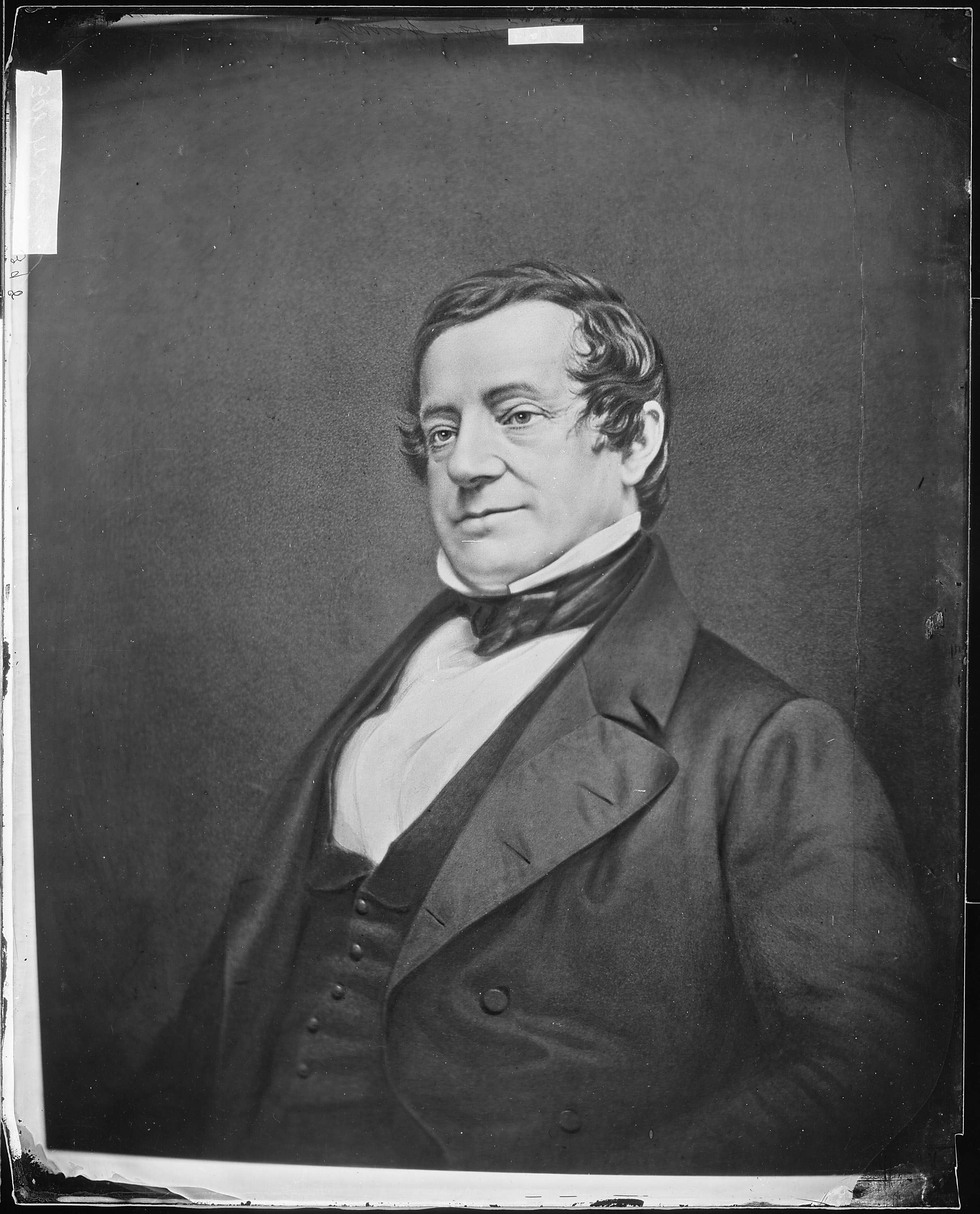

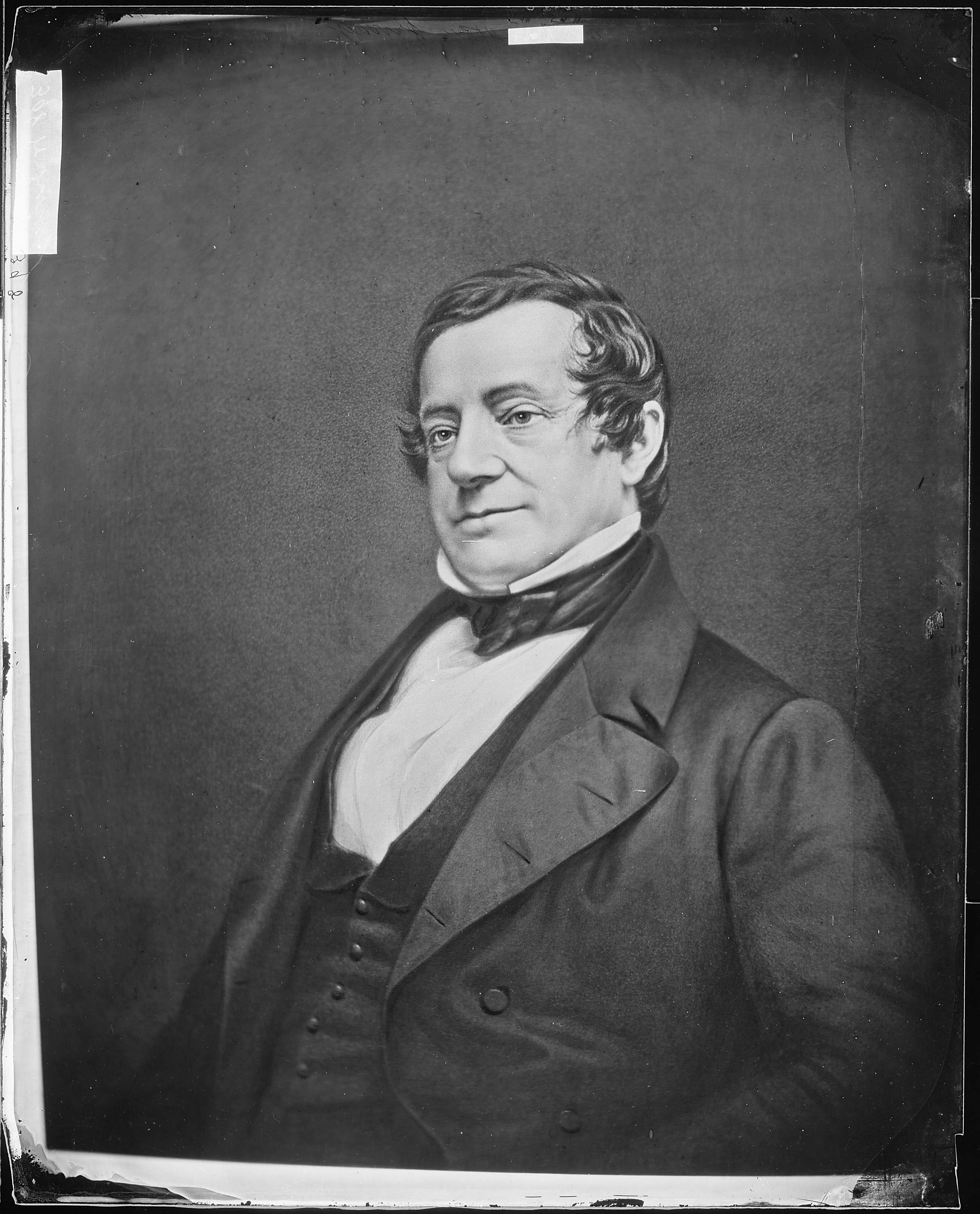

Washington Irving

ca. 1860 - 1865

This primary source comes from the Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer.

National Archives Identifier: 528291

Full Citation: Photograph 111-B-4144; Washington Irving; ca. 1860 - 1865; Mathew Brady Photographs of Civil War-Era Personalities and Scenes, 1921 - 1940; Records of the Office of the Chief Signal Officer, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/washington-irving, April 24, 2024]Washington Irving

Page 1

Document

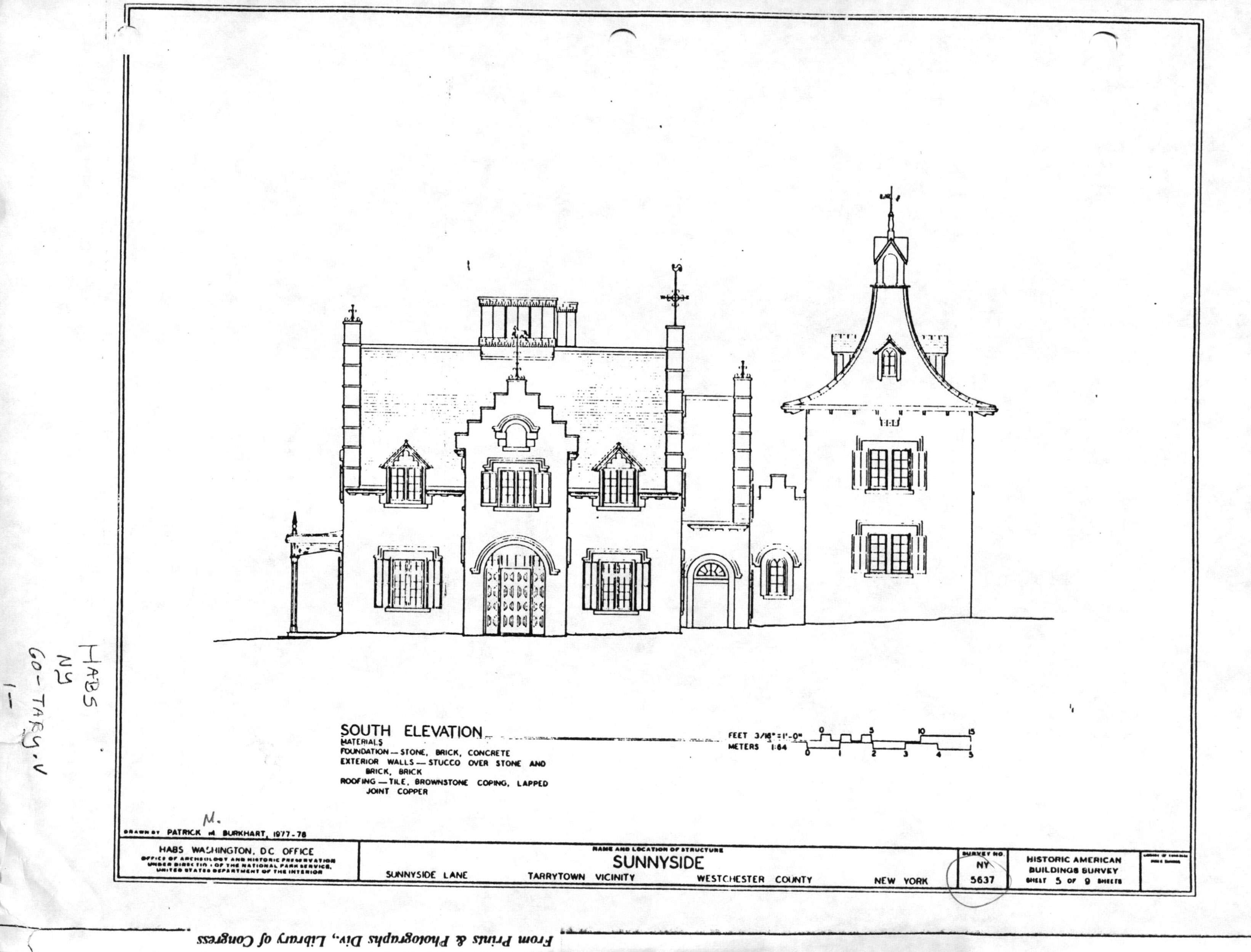

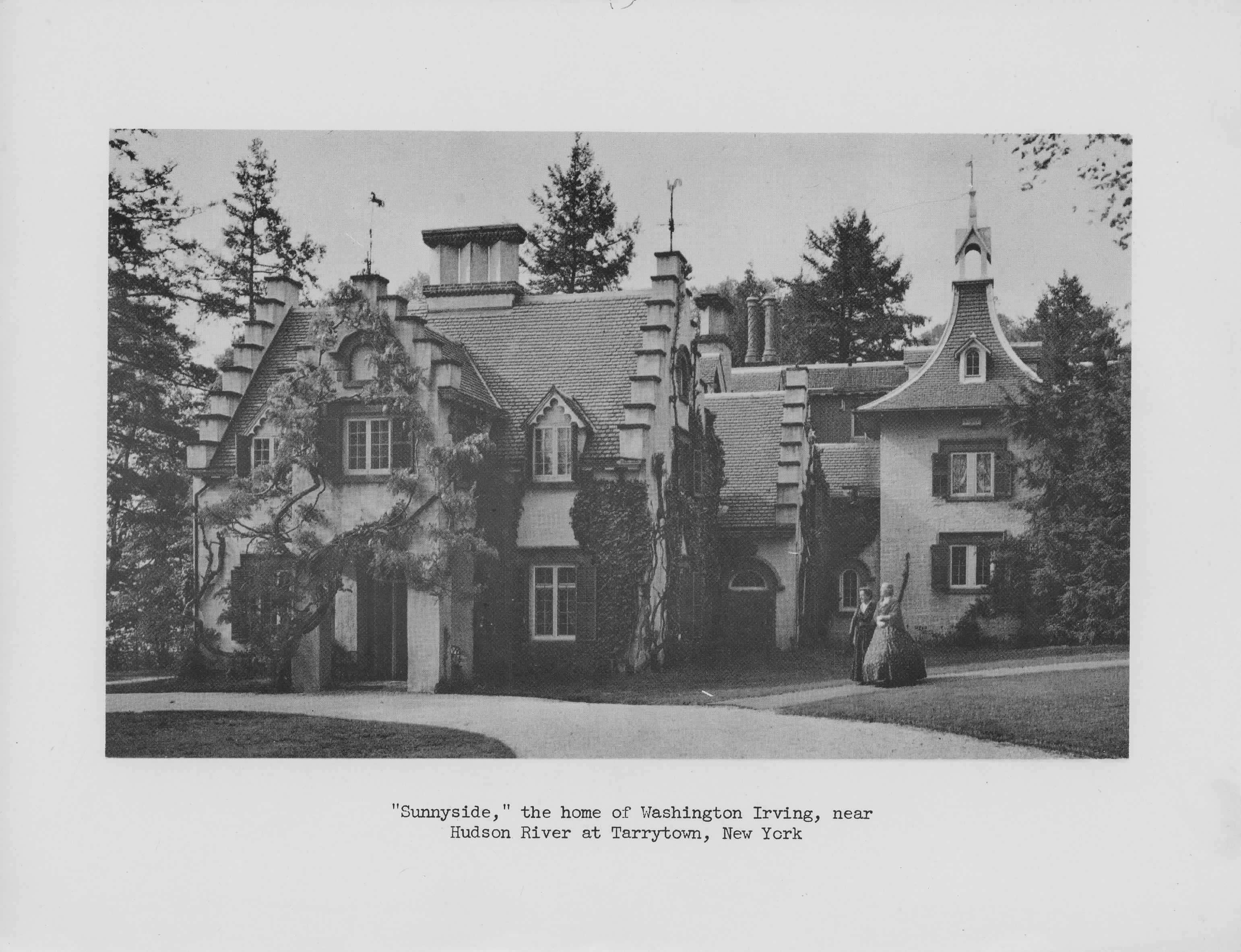

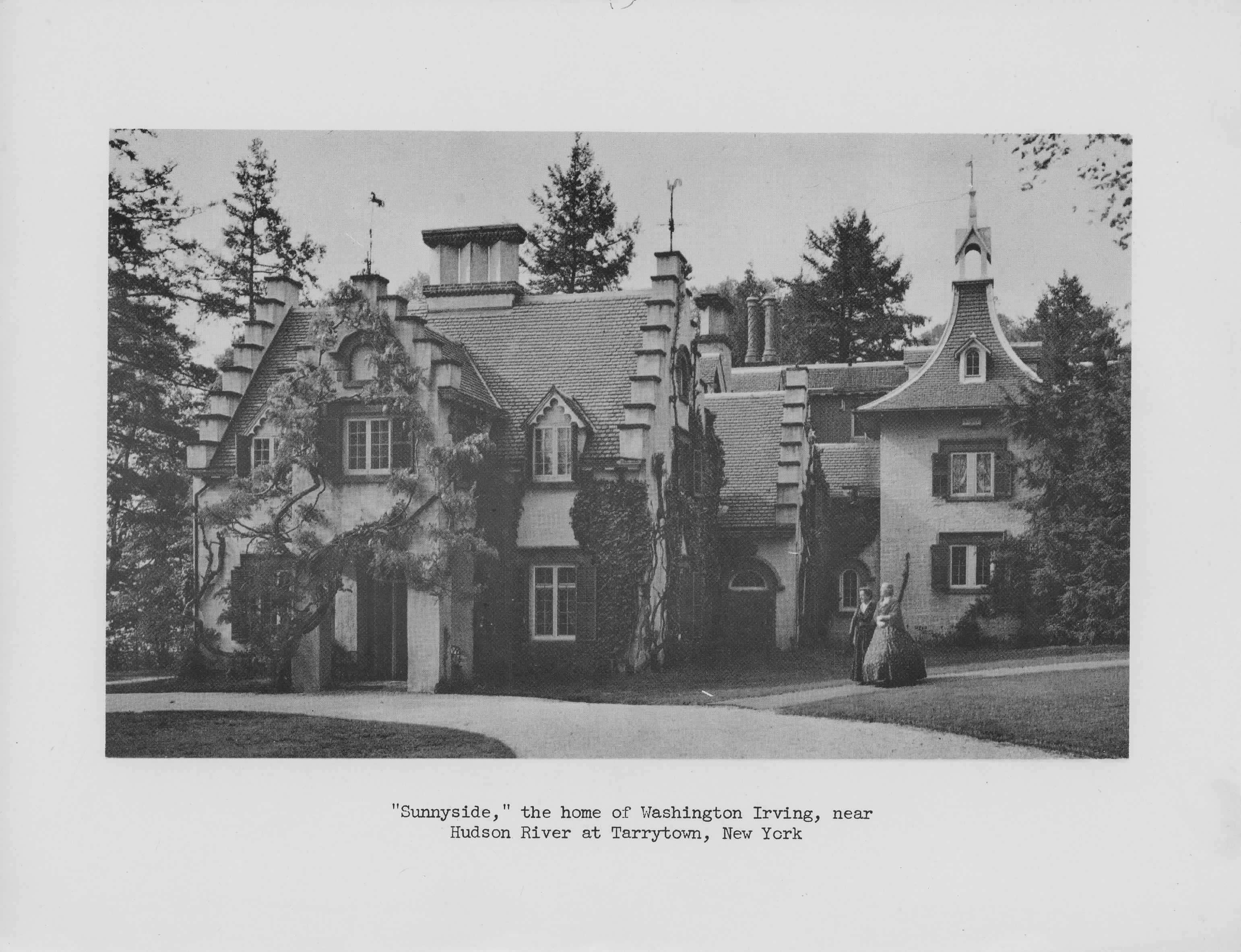

New York NHL Sunnyside

1975

Sunnyside was author Washington Irving's estate, located on the Hudson River near Tarrytown, New York. These images and the following descriptions were included with the nomination to add Sunnyside to the National Register of Historic Places.

In 1832, Washington Irving returned to America after 17 years in Europe, to find himself regarded as the foremost prose writer in America. In 1835, he purchased the Van Tassel cottage, a 17th century Dutch house on the Hudson River, below Tarrytown, the setting of some of Irving's bestloved tales. For the last 24 years of his life Irving lived and worked at his estate, Sunnyside, enlarging the house and landscaping the grounds.

Washington Irving was born on April 3, 1783, the 11th and last child of William and Sarah Irving, a Scottish-English mercantile family in New York. As a youth, Irving led a sheltered life, but still managed to pursue his interests in theater, art, music, travel, and social occasions.

Following a trip to Europe between 1804 and 1806, Irving returned to New York, studied for and was admitted to the bar, and began to write humorous short pieces. His first extended project, A History of New York, written under the pseudonym of Diedrich Knickerbocker, was published in 1809. It was an elaborate and intricate satire of old Dutch families of New Netherlands which required much of his time to complete. In this same year, Matilda Hoffman, a young lady whom Irving was deeply attached to, died suddenly. Irving was strongly affected by this and remained a bachelor for life. In 1815, Irving and his brother Peter sailed for London to attend to the family business which was in great disorder. By 1818, the firm was bankrupt and Irving determined to become a fulltime author.

The products of the decision were soon forthcoming and they included; The Sketch Book, 1819-1820; Bracebridge Hall, 1822-1825; The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, published in three volumes in 1828 after his stay as an attache at the United States Legation in Madrid; and A Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada in 1829. Until 1832 he acted as Secretary of the United States Legation in London. In this period he produced two other works including the Alhambra, or the "Spanish Sketch Book," in 1832. During this time, Irving traveled throughout Europe, where he was well-accepted in social and literary circles.

With the exception of "Rip Van Winkle," and the "Legend of Sleepy Hollow," in the Sketch Book, his works were concerned with the nostalgia and history of the Old World. Although romantic and sentimental, his books gained critical and financial success, and earned him praise from such authors as Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell and Thomas Moore, and advice from Sir Walter Scott.

In 1832, Irving returned to America after an absence of 17 years, to be greeted by widespread acclaim and appreciation for introducing American literature to the European mainstream. Irving embarked on a trip through the Midwest and then returned to New York. In 1835 he purchased the Van Tassel cottage at Tarrytown and devoted his time toward the reconstruction of that house in his own personal style. In these years following, Irving's writings became less inspired and tended more towards editing older writings and republishing collected works. Once his house was completed, he invited the motherless family of his brother Ebenezer to live with him at Sunnyside and his little "snuggery" was frequently so crowded that he was forced to sleep in his study.

In 1842, Irving was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of Spain by President Tyler. Irving had previously been offered the candidacy for the Mayor of New York City and the Secretaryship of the Navy in Van Buren's cabinet, but Irving chose to avoid these more political posts.

Irving returned from Spain in 1846 to Sunnyside, where he began to work on his monumental biography, Life of George Washington. In 1849, he published Oliver Goldsmith: A Biography, and followed this with the two-volume Mahomet and His Successors. The fifth and final volume of Washington's biography had just been published when Irving died quietly at Sunnyside on November 28, 1859. His funeral, which was attended by thousands, was held at Christ Episcopal Church in Tarrytown, and he was buried in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, also in Tarrytown.

In 1945, John D. Rockefeller Jr. bought Sunnyside to save it from demolition and open it to the public.

In 1832, Washington Irving returned to America after 17 years in Europe, to find himself regarded as the foremost prose writer in America. In 1835, he purchased the Van Tassel cottage, a 17th century Dutch house on the Hudson River, below Tarrytown, the setting of some of Irving's bestloved tales. For the last 24 years of his life Irving lived and worked at his estate, Sunnyside, enlarging the house and landscaping the grounds.

Washington Irving was born on April 3, 1783, the 11th and last child of William and Sarah Irving, a Scottish-English mercantile family in New York. As a youth, Irving led a sheltered life, but still managed to pursue his interests in theater, art, music, travel, and social occasions.

Following a trip to Europe between 1804 and 1806, Irving returned to New York, studied for and was admitted to the bar, and began to write humorous short pieces. His first extended project, A History of New York, written under the pseudonym of Diedrich Knickerbocker, was published in 1809. It was an elaborate and intricate satire of old Dutch families of New Netherlands which required much of his time to complete. In this same year, Matilda Hoffman, a young lady whom Irving was deeply attached to, died suddenly. Irving was strongly affected by this and remained a bachelor for life. In 1815, Irving and his brother Peter sailed for London to attend to the family business which was in great disorder. By 1818, the firm was bankrupt and Irving determined to become a fulltime author.

The products of the decision were soon forthcoming and they included; The Sketch Book, 1819-1820; Bracebridge Hall, 1822-1825; The Life and Voyages of Christopher Columbus, published in three volumes in 1828 after his stay as an attache at the United States Legation in Madrid; and A Chronicle of the Conquest of Granada in 1829. Until 1832 he acted as Secretary of the United States Legation in London. In this period he produced two other works including the Alhambra, or the "Spanish Sketch Book," in 1832. During this time, Irving traveled throughout Europe, where he was well-accepted in social and literary circles.

With the exception of "Rip Van Winkle," and the "Legend of Sleepy Hollow," in the Sketch Book, his works were concerned with the nostalgia and history of the Old World. Although romantic and sentimental, his books gained critical and financial success, and earned him praise from such authors as Lord Byron, Thomas Campbell and Thomas Moore, and advice from Sir Walter Scott.

In 1832, Irving returned to America after an absence of 17 years, to be greeted by widespread acclaim and appreciation for introducing American literature to the European mainstream. Irving embarked on a trip through the Midwest and then returned to New York. In 1835 he purchased the Van Tassel cottage at Tarrytown and devoted his time toward the reconstruction of that house in his own personal style. In these years following, Irving's writings became less inspired and tended more towards editing older writings and republishing collected works. Once his house was completed, he invited the motherless family of his brother Ebenezer to live with him at Sunnyside and his little "snuggery" was frequently so crowded that he was forced to sleep in his study.

In 1842, Irving was appointed Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the Court of Spain by President Tyler. Irving had previously been offered the candidacy for the Mayor of New York City and the Secretaryship of the Navy in Van Buren's cabinet, but Irving chose to avoid these more political posts.

Irving returned from Spain in 1846 to Sunnyside, where he began to work on his monumental biography, Life of George Washington. In 1849, he published Oliver Goldsmith: A Biography, and followed this with the two-volume Mahomet and His Successors. The fifth and final volume of Washington's biography had just been published when Irving died quietly at Sunnyside on November 28, 1859. His funeral, which was attended by thousands, was held at Christ Episcopal Church in Tarrytown, and he was buried in the Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, also in Tarrytown.

In 1945, John D. Rockefeller Jr. bought Sunnyside to save it from demolition and open it to the public.

This primary source comes from the Records of the National Park Service.

National Archives Identifier: 75316130

Full Citation: New York NHL Sunnyside; 1975; National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records: New York; National Register of Historic Places and National Historic Landmarks Program Records, 2013 - 2017; Records of the National Park Service, ; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/sunnyside-washington-irving, April 24, 2024]New York NHL Sunnyside

Page 1

New York NHL Sunnyside

Page 2