Letter to President Lincoln

Making Connections

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

Read Annie Davis's letter to President Lincoln, and the document that follows the letter each time. Reply to the question and decide whether that document would have freed this enslaved woman. Be sure to click on "View Document Details" for help interpreting the document.Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

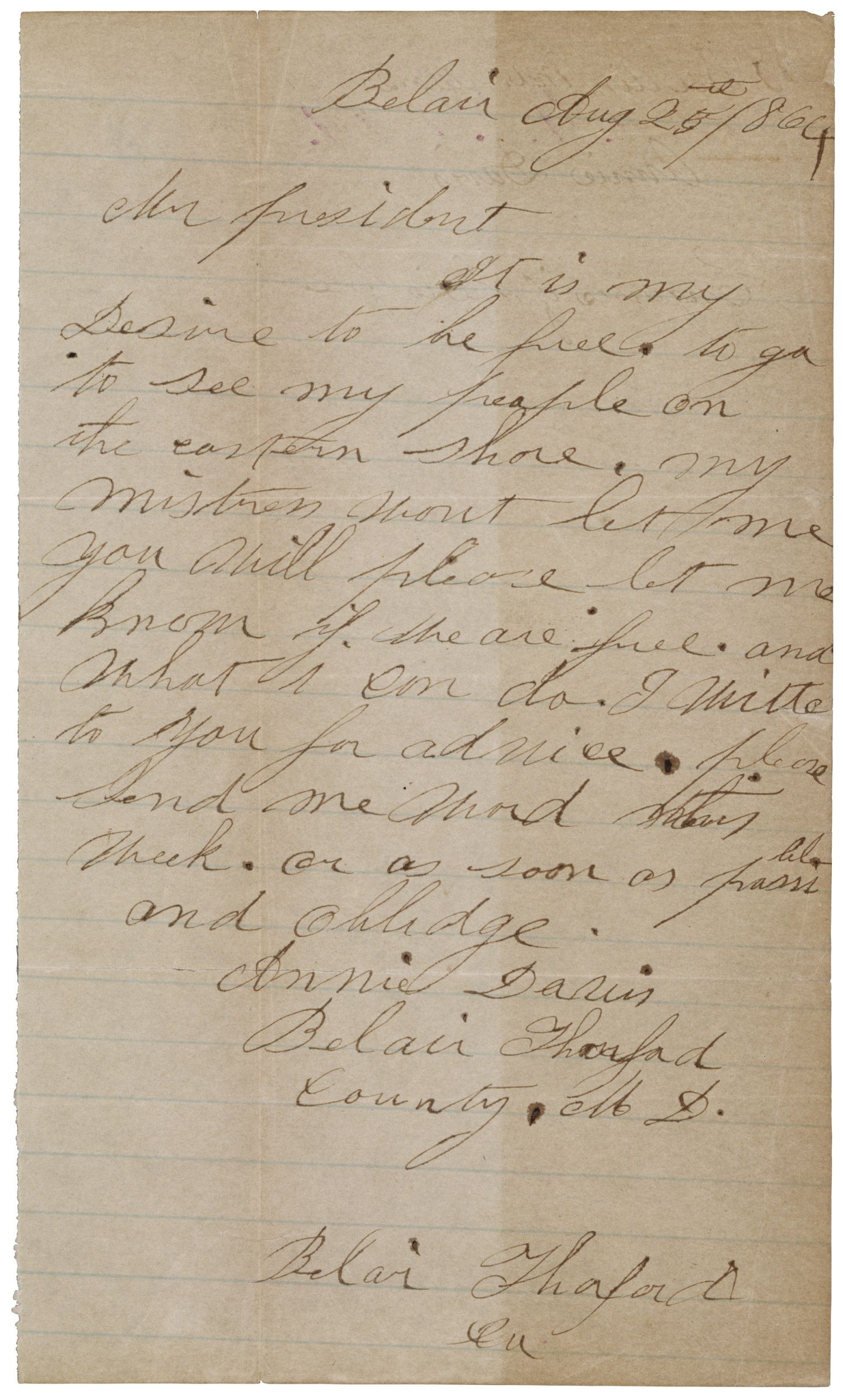

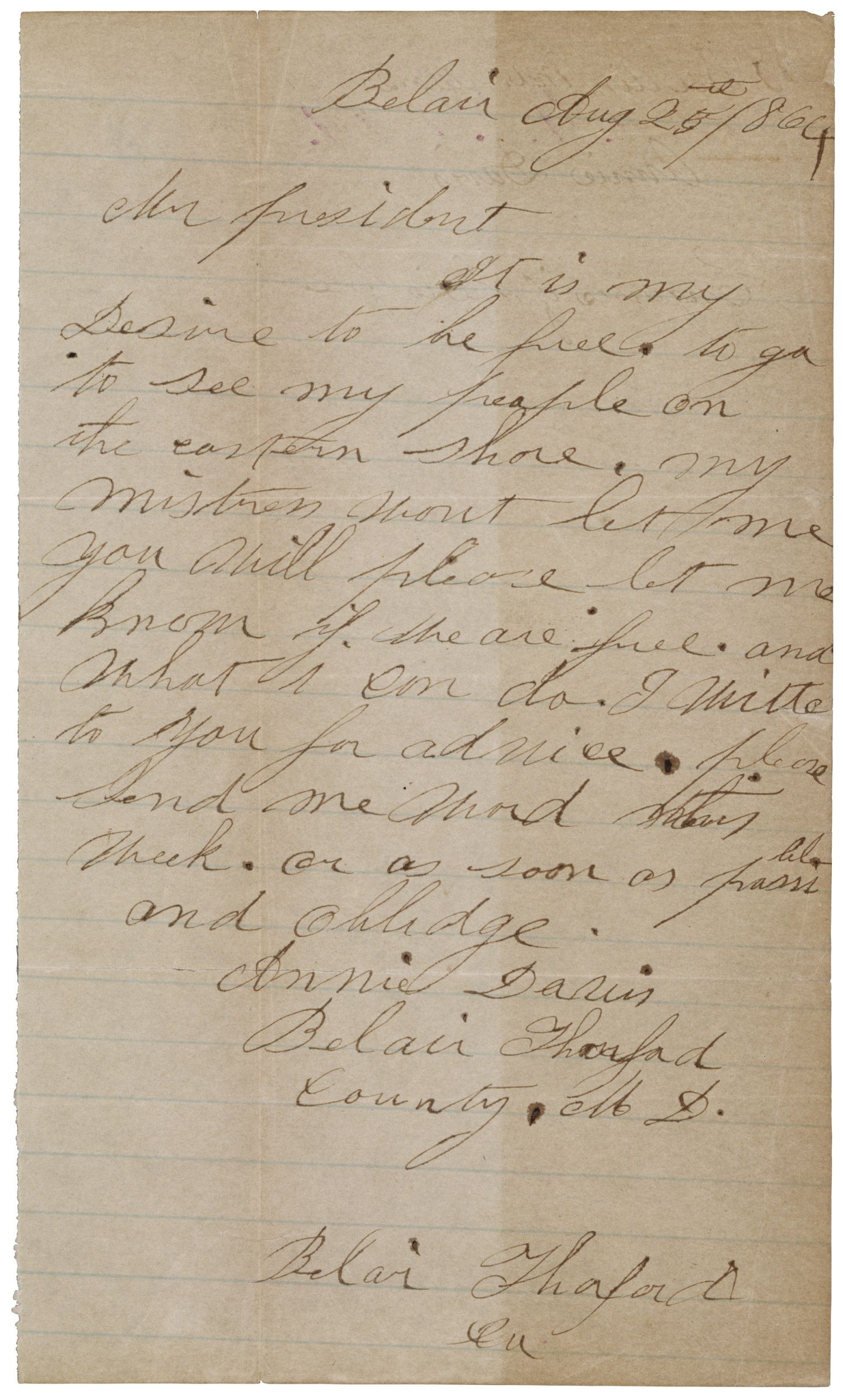

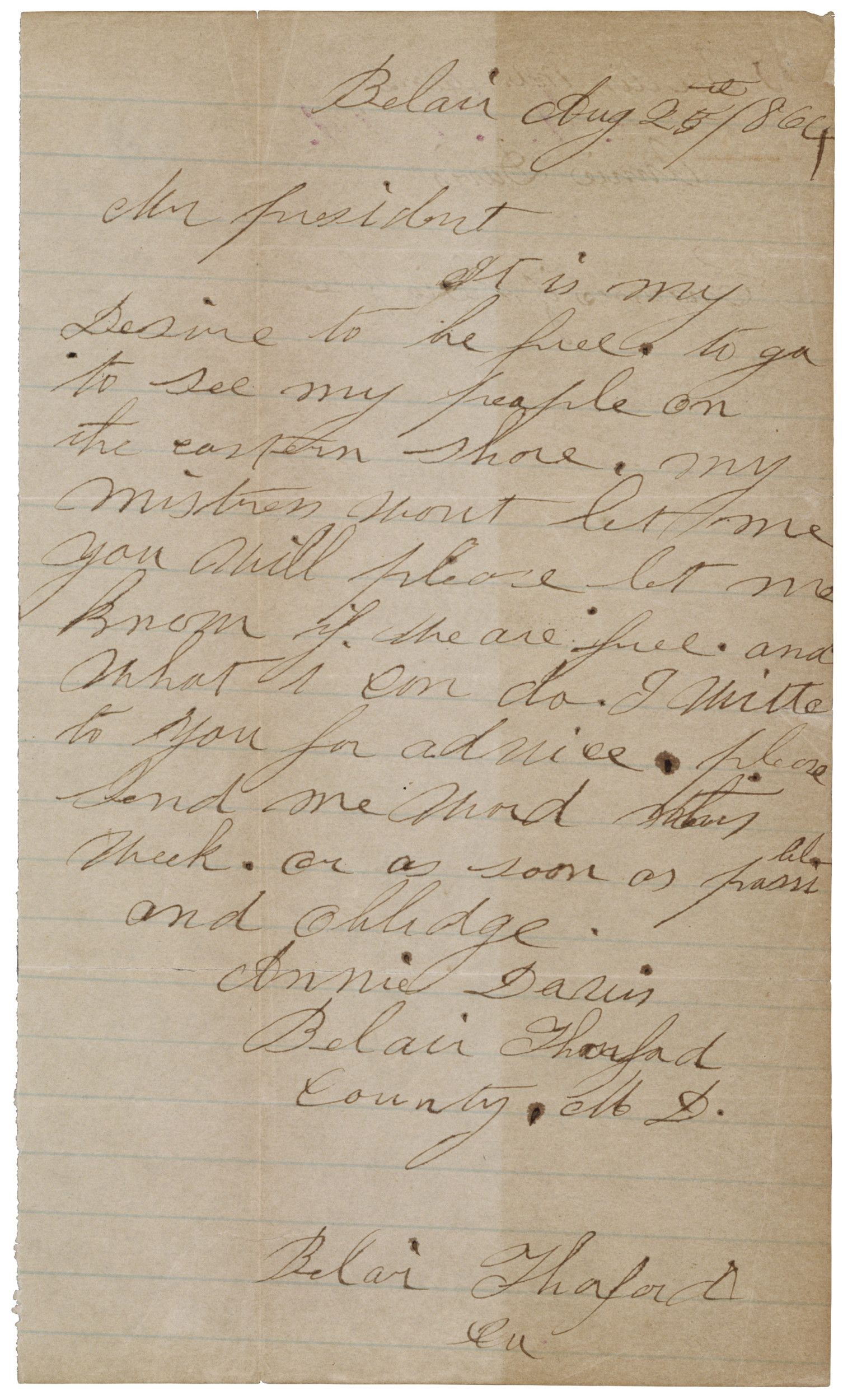

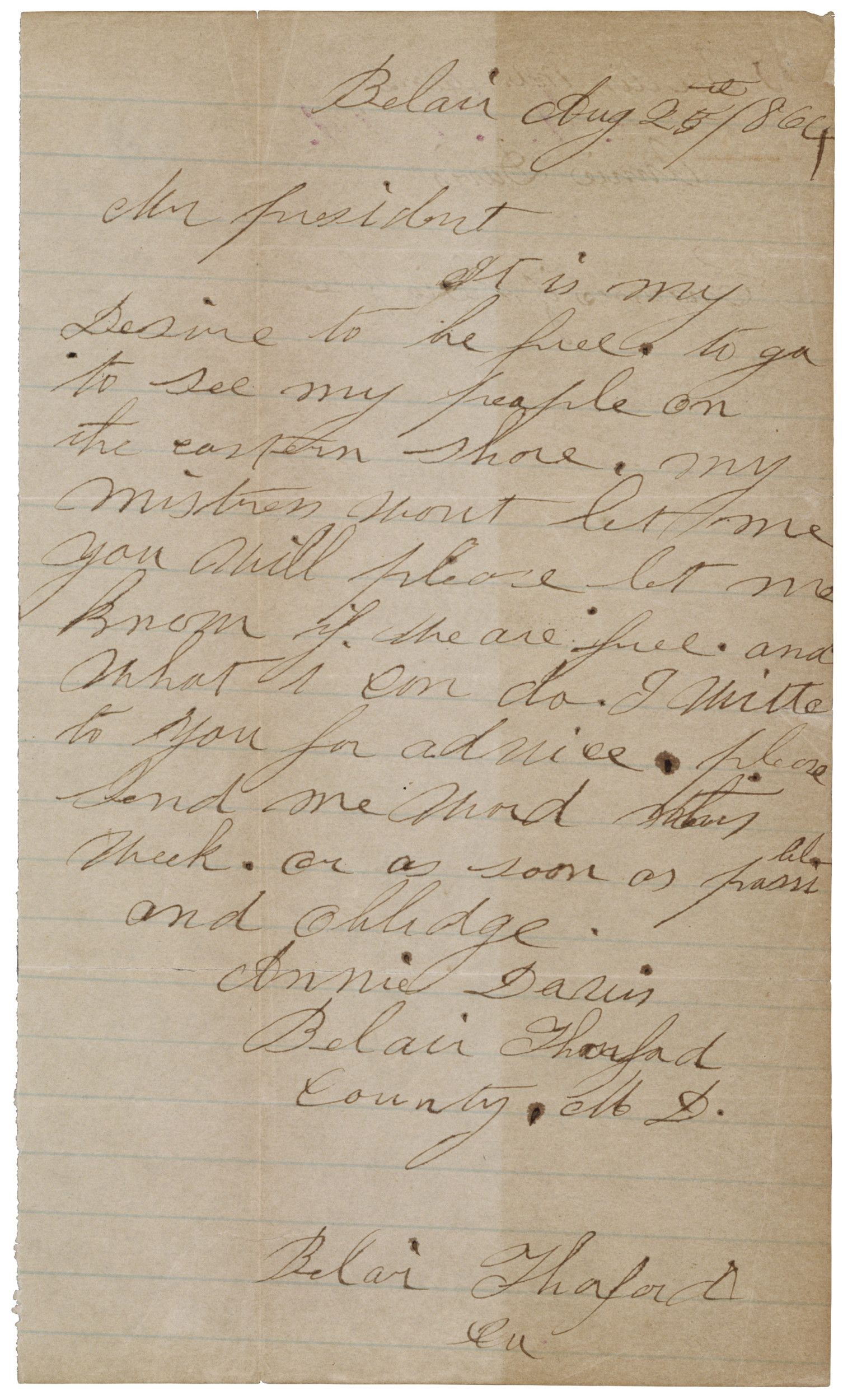

Letter to President Lincoln

Making Connections

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Fill in any blanks in the sequence with your thoughts and write your conclusion response in the space provided.Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

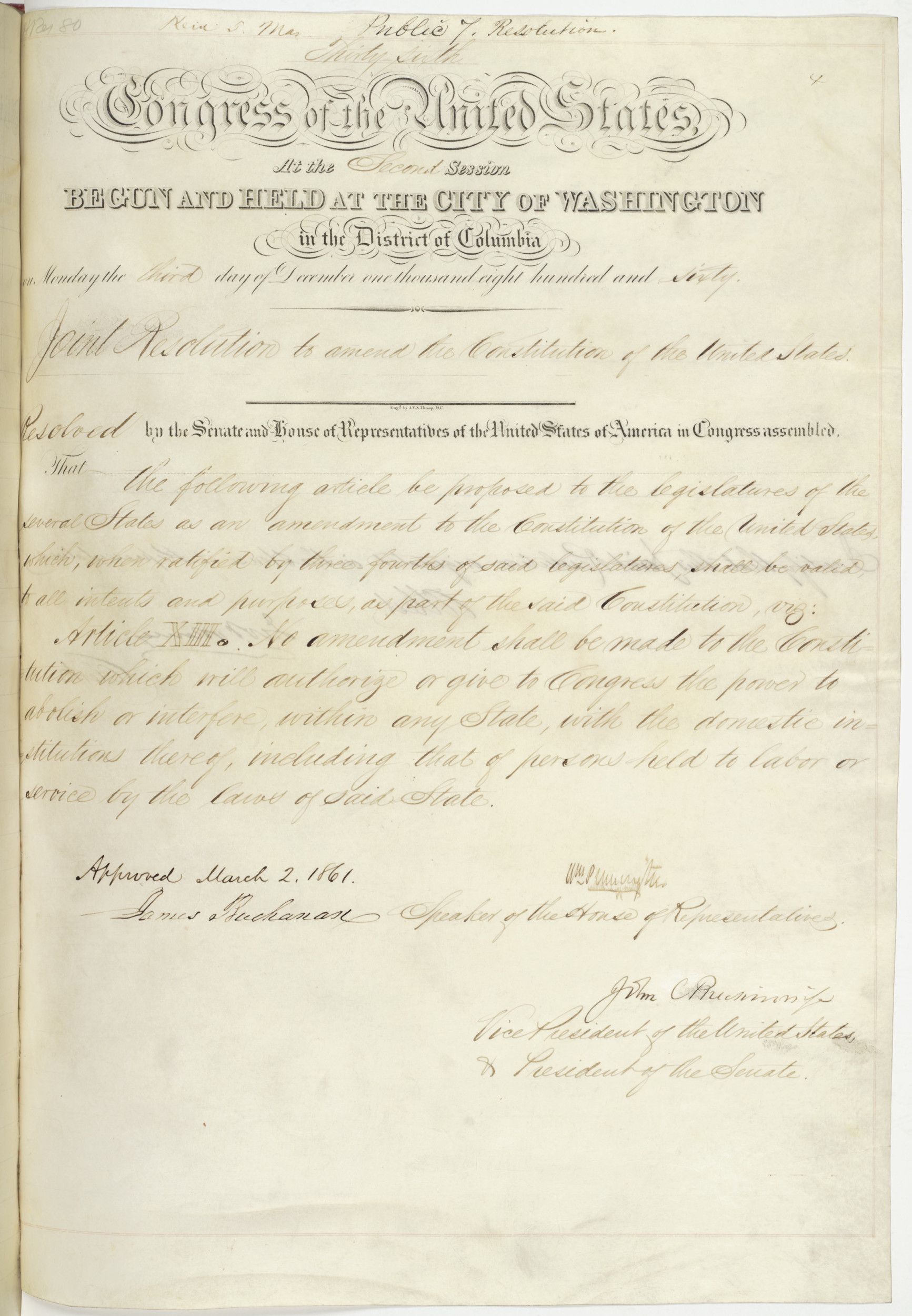

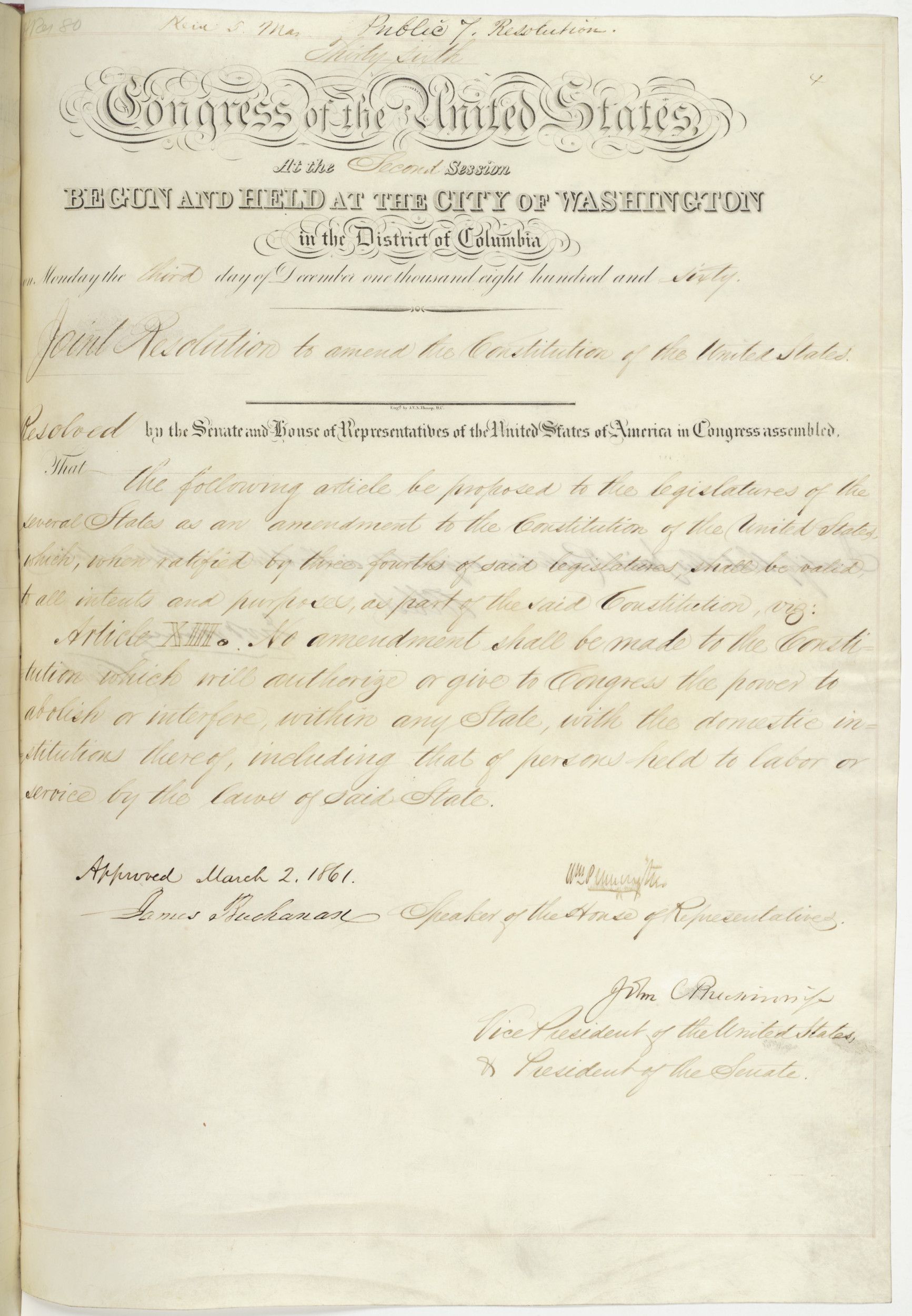

Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

What would it have meant to Annie Davis if this amendment had been ratified by the states?

Enter your response

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Emancipation Proclamation

The letter from Annie Davis is written after the Emancipation Proclamation. Not all enslaved people heard about their freedom. Did the Emancipation Proclamation free Annie Davis so she could visit her people on the Eastern Shore?

Enter your response

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

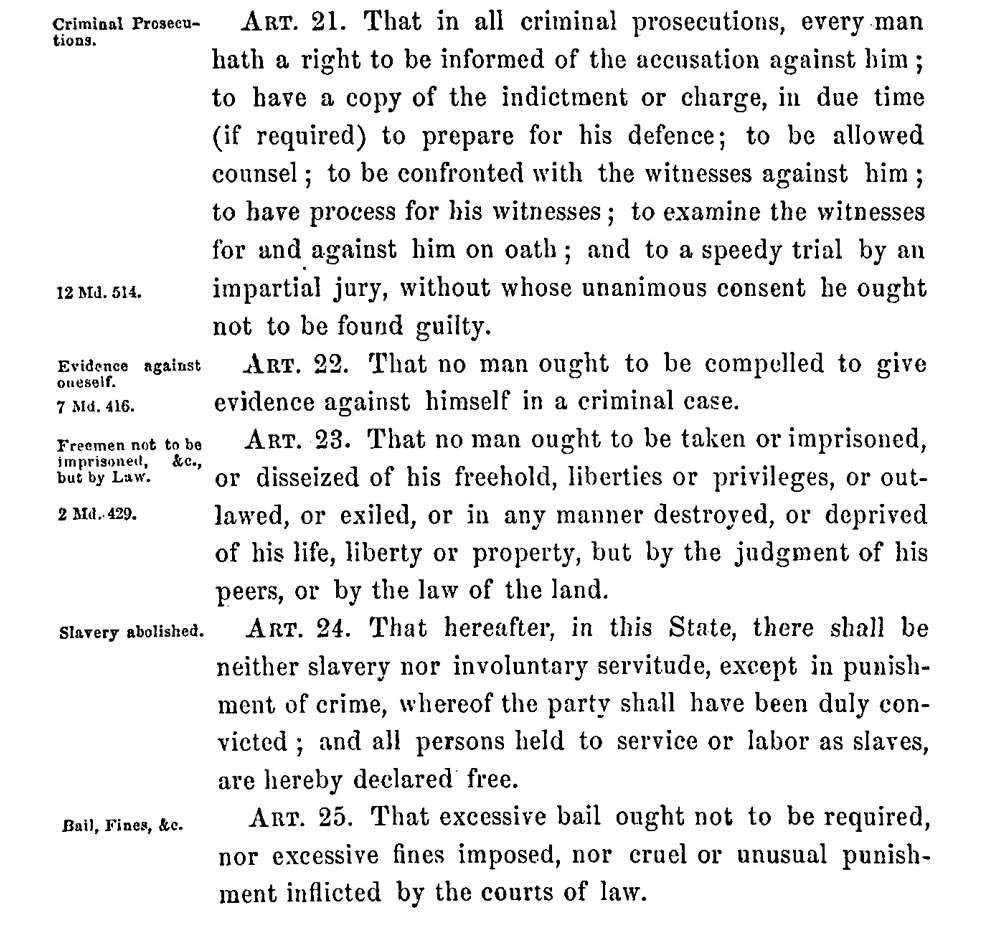

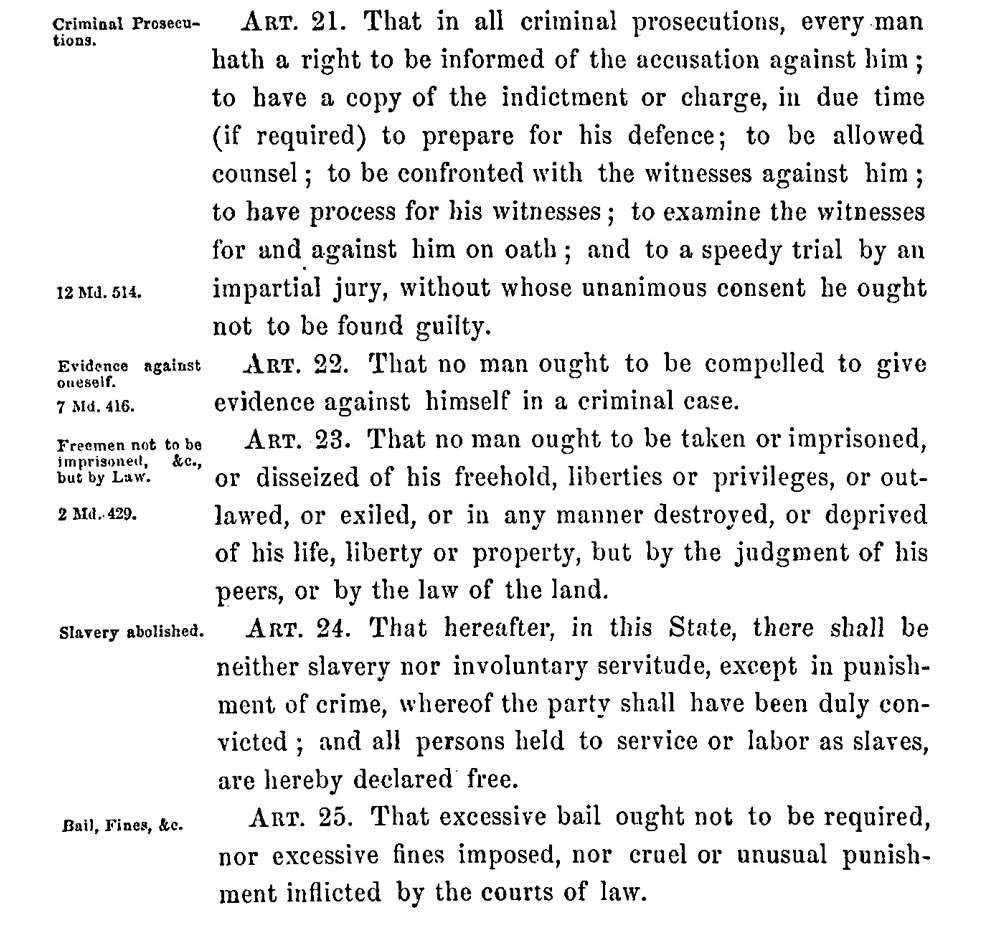

Selection from the Maryland Constitution of 1864; Maryland Archives Online, Constitutional Records, Volume 102, Page 723; Maryland State Archives [Online Version, http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000102/html/am102--723.html]

Since she was living in Maryland, what would the ratification of Maryland`s 1864 Constitution have meant to Annie Davis? (Davis wrote her letter on August 25th and the Maryland Constitution went into effect on October 29, 1864.)

Enter your response

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

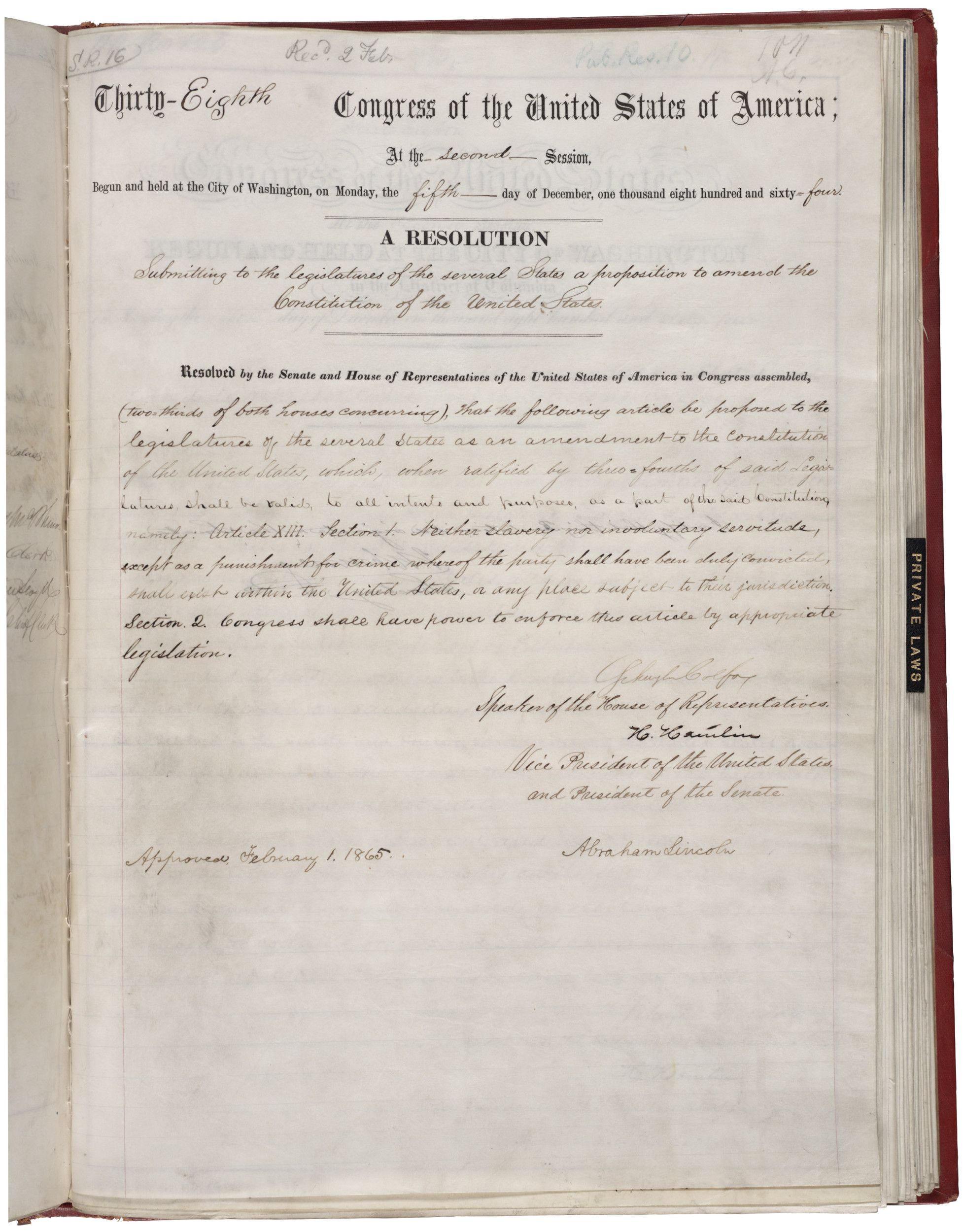

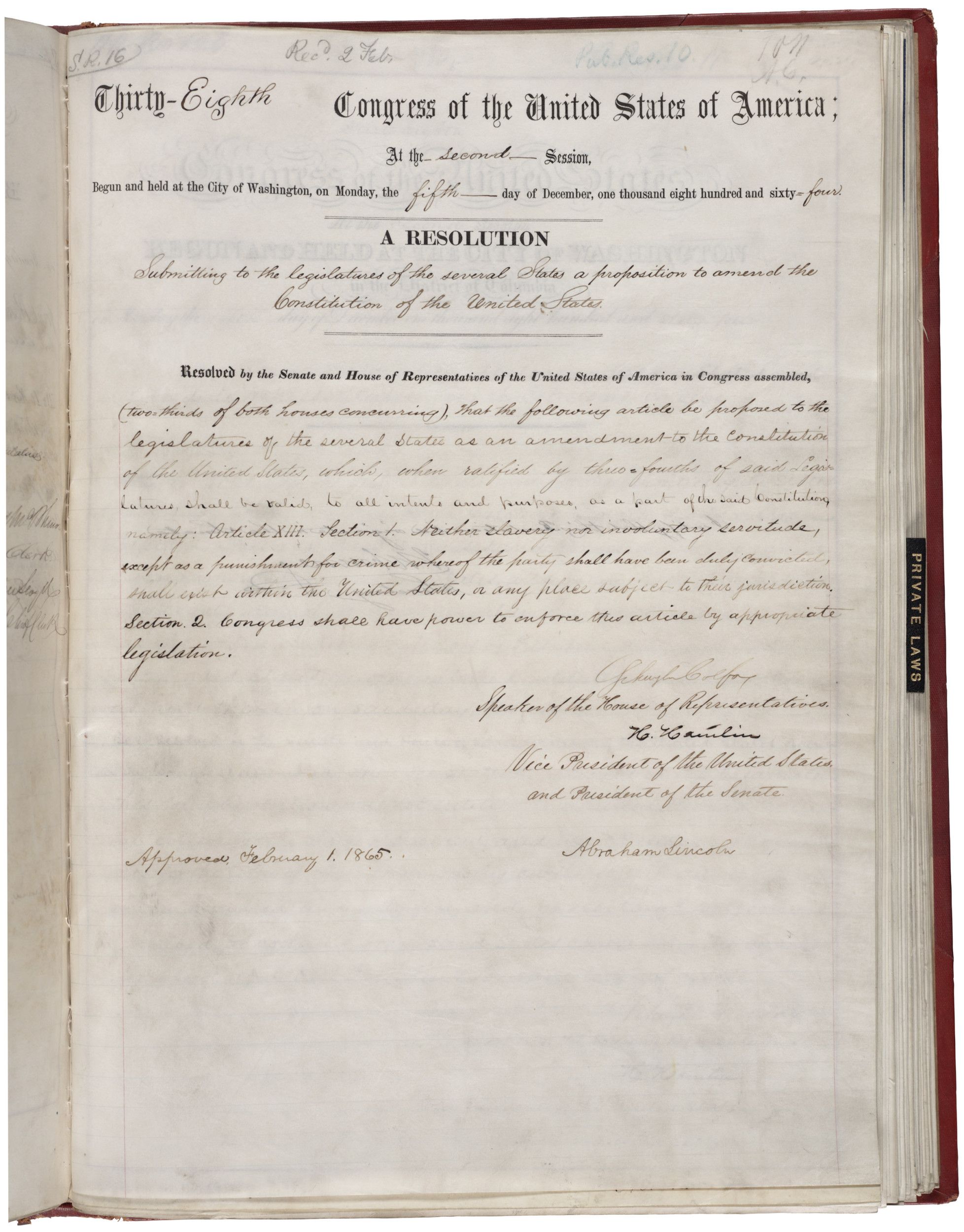

Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Would Annie Davis have been freed with the passage of this amendment?

Enter your response

1

Activity Element

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

2

Activity Element

Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

Page 2

3

Activity Element

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

4

Activity Element

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 1

5

Activity Element

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

6

Activity Element

Selection from the Maryland Constitution of 1864; Maryland Archives Online, Constitutional Records, Volume 102, Page 723; Maryland State Archives [Online Version, http://msa.maryland.gov/megafile/msa/speccol/sc2900/sc2908/000001/000102/html/am102--723.html]

7

Activity Element

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

8

Activity Element

Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 2

Conclusion

Letter to President Lincoln

Making Connections

- Which document freed Annie Davis?

- Which document(s) did not free Annie and why?

- We don't have proof whether President Lincoln ever wrote Annie Davis back. Write a letter to Annie Davis as President Lincoln and explain her status.

Your Response

Document

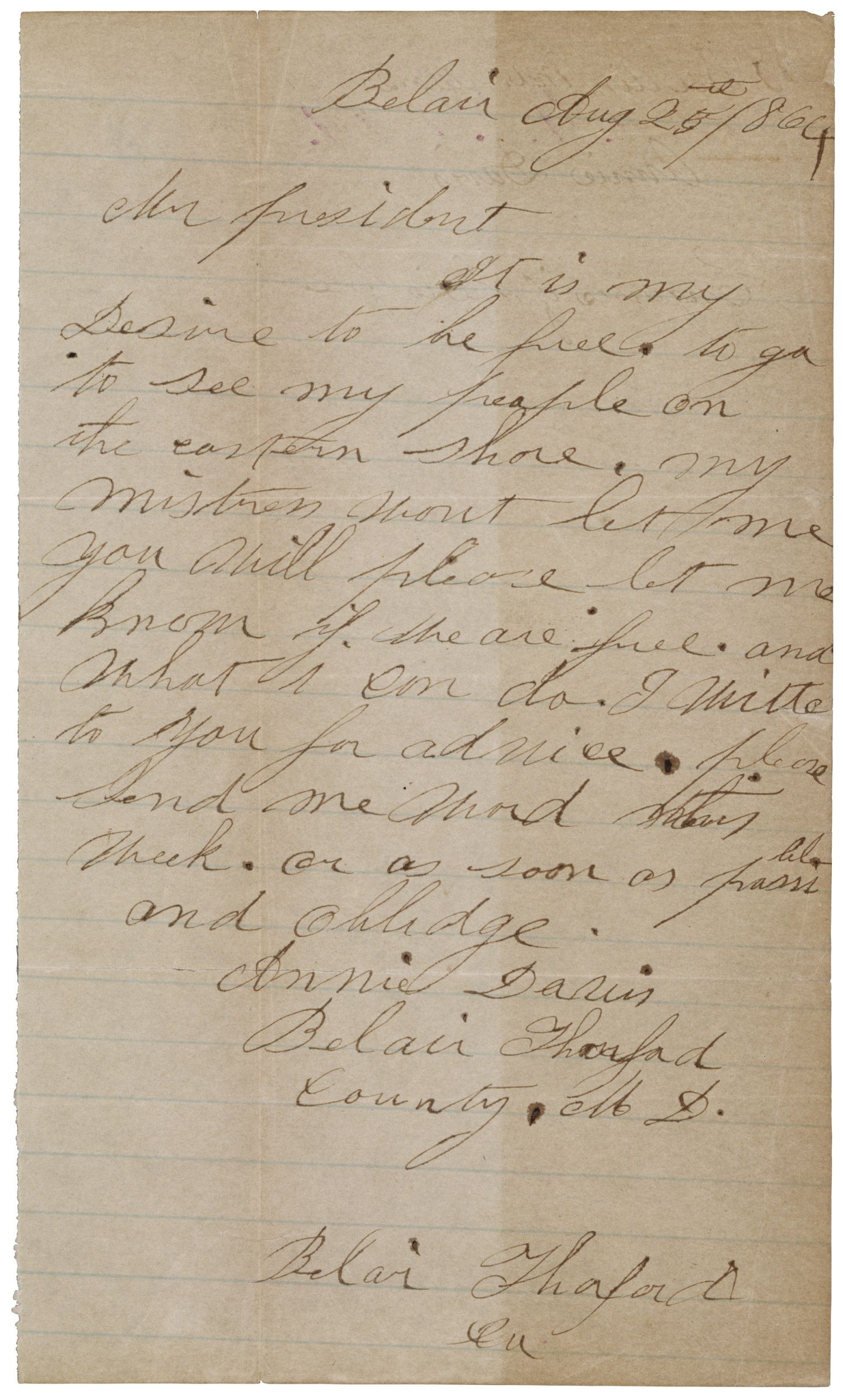

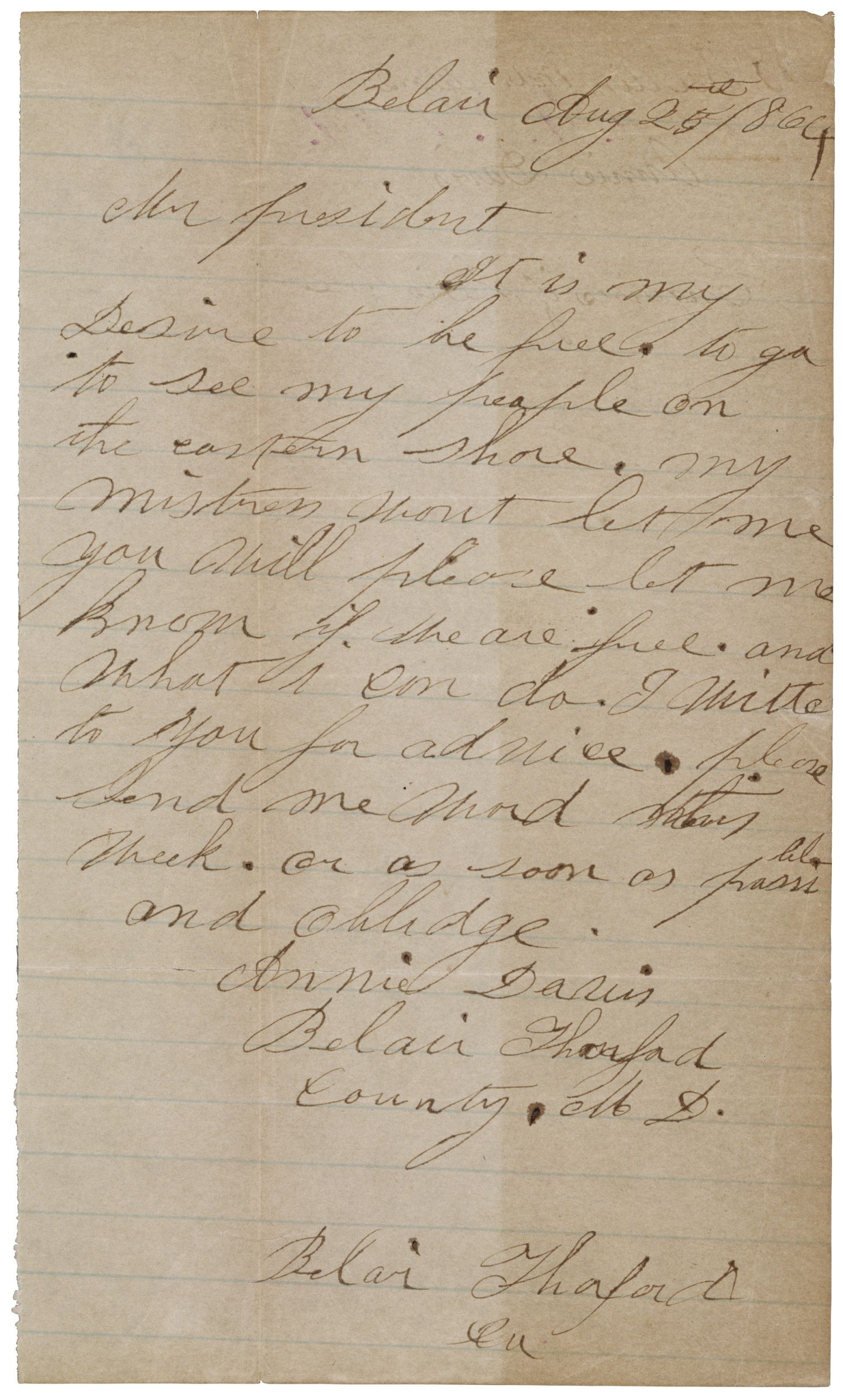

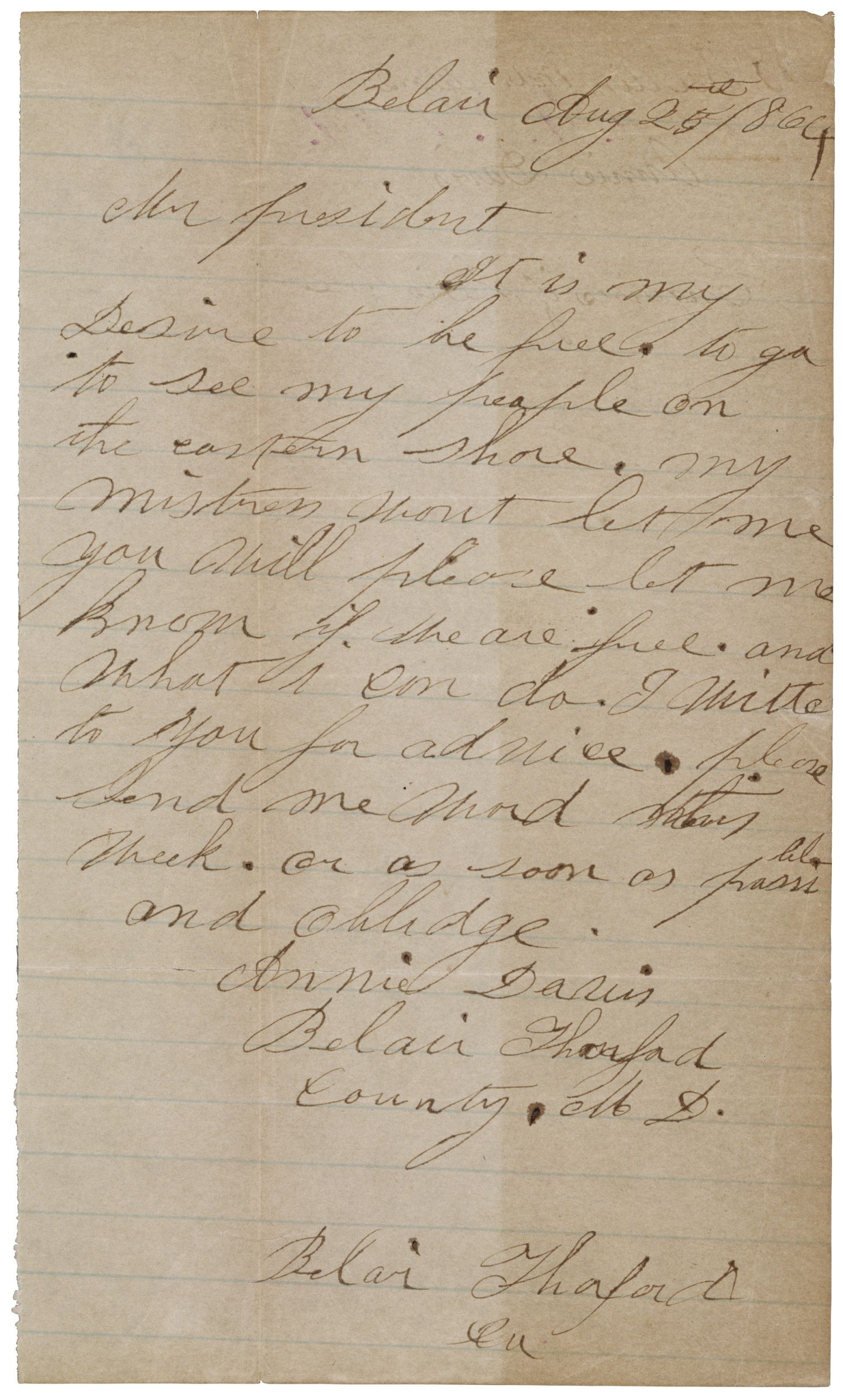

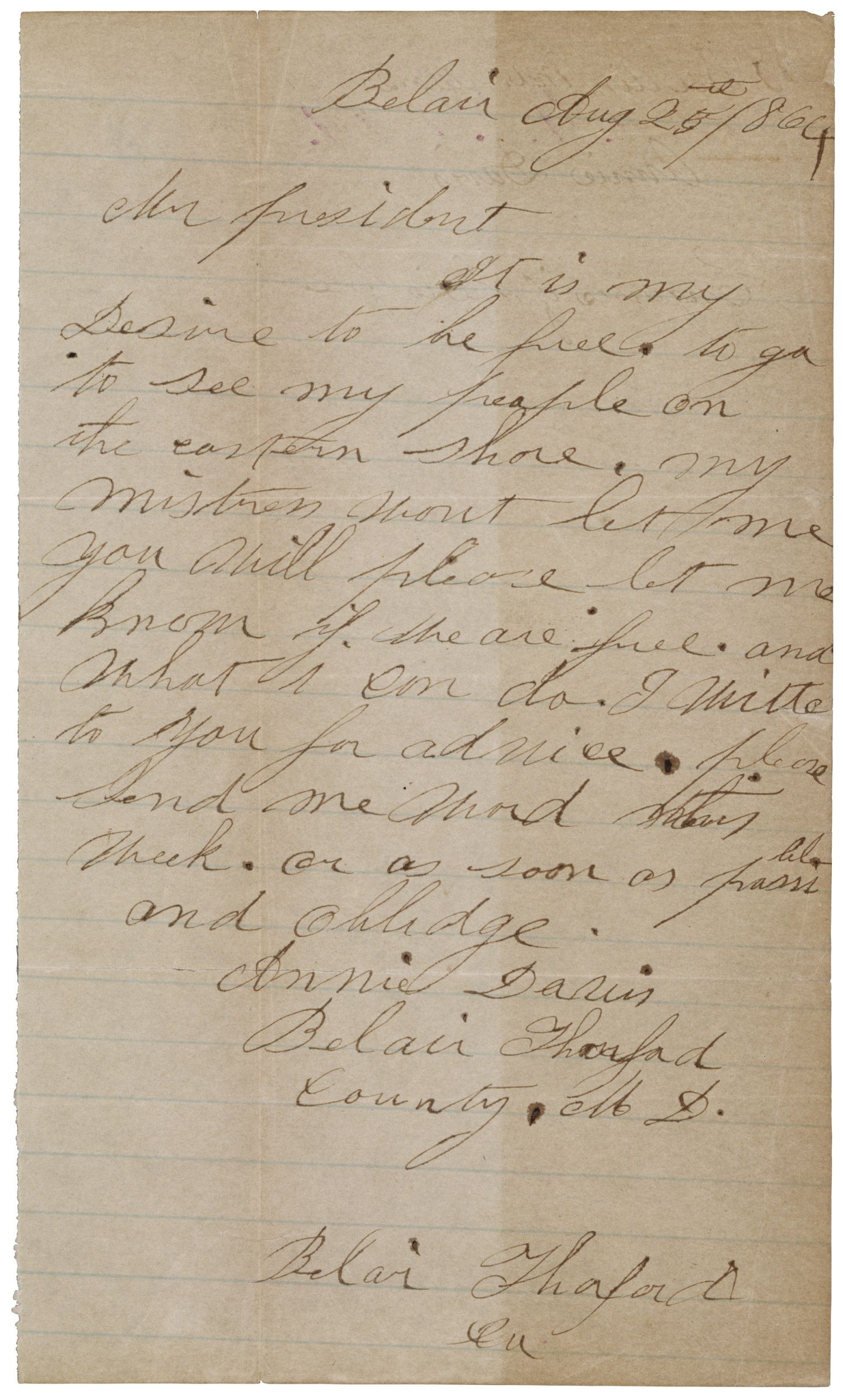

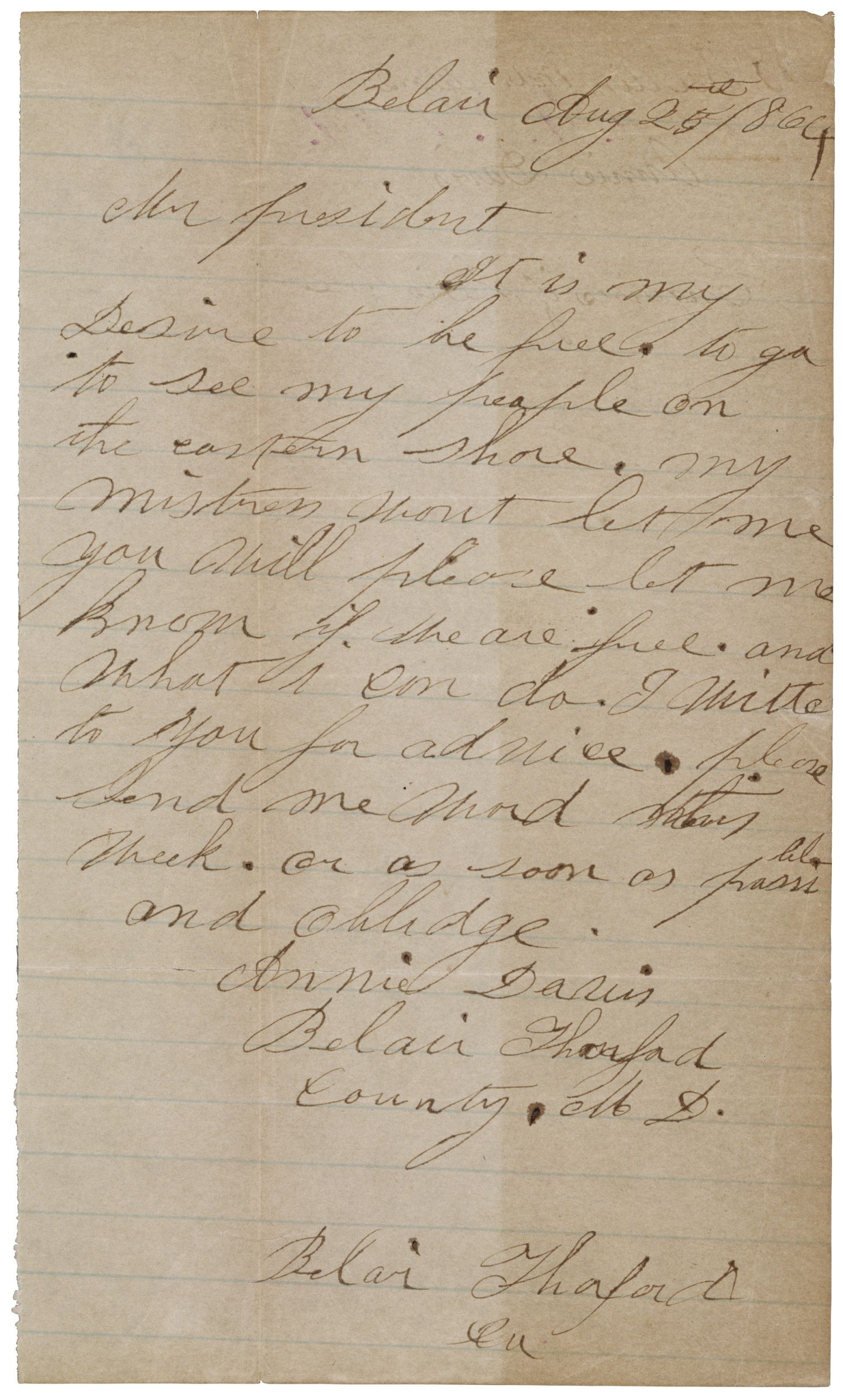

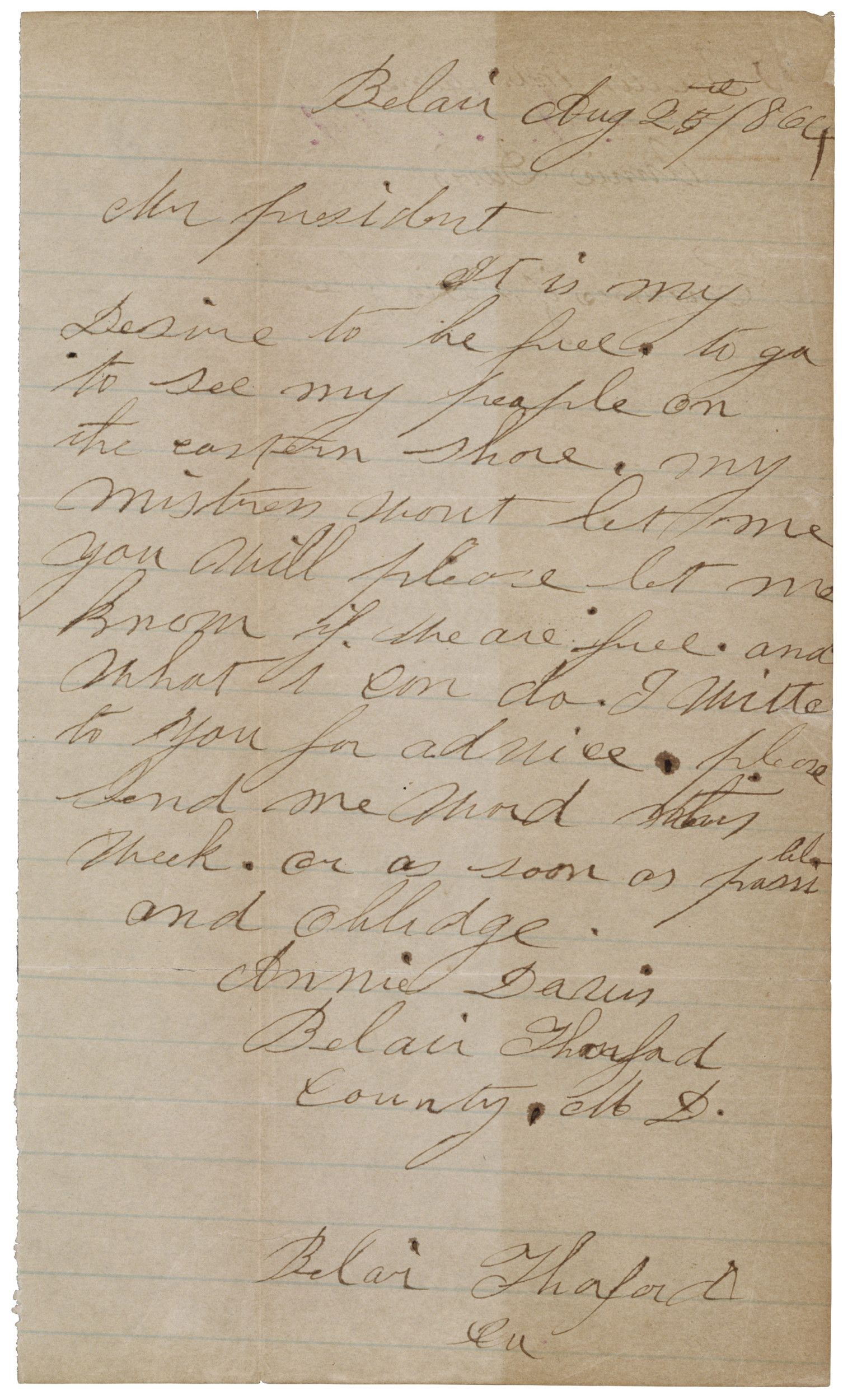

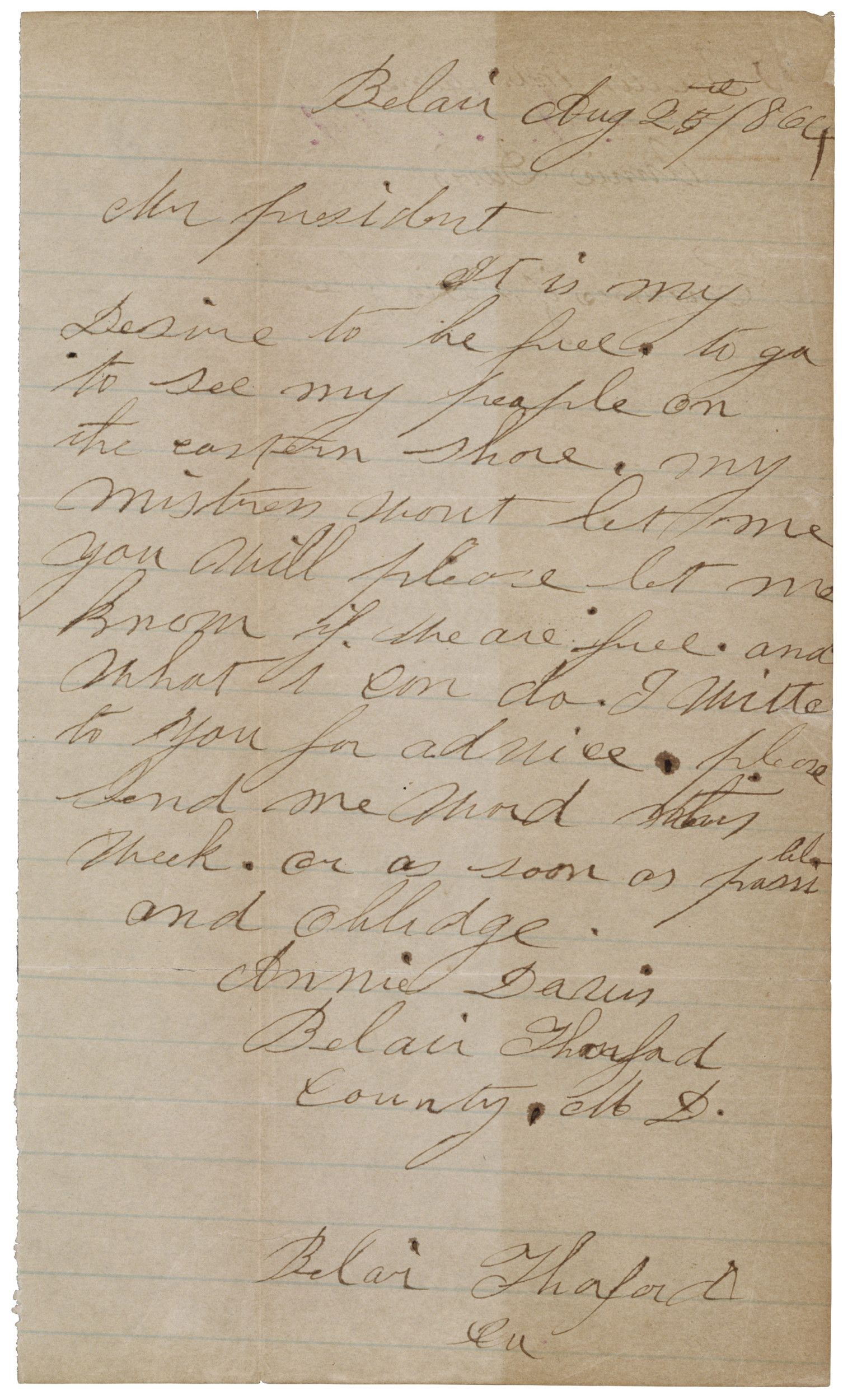

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

8/25/1864

"Mr. President, It is my Desire to be free," wrote Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln, 20 months after he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Writing from Belair, Maryland, she continued, "Will you please let me know if we are free."

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Transcript

Belair Aug 25th 1864Mr. President

It is my Desire to be free. to go to see my people on the eastern shore. my mistress wont let me you will please let me know if we are free. and what I can do. I write to you for advice. please send me word this[?] week. or as soon as possible. and oblidge.

Annie Davis

Belair Thaford

County. Mt D.

Belair Thaford

Cu[?]

This primary source comes from the Records of the Adjutant General's Office.

National Archives Identifier: 4662543

Full Citation: Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln; 8/25/1864; 1864 D-304; Letters Received, 1863-1888; Records of the Adjutant General's Office, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/letter-from-annie-davis-to-abraham-lincoln, April 24, 2024]Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

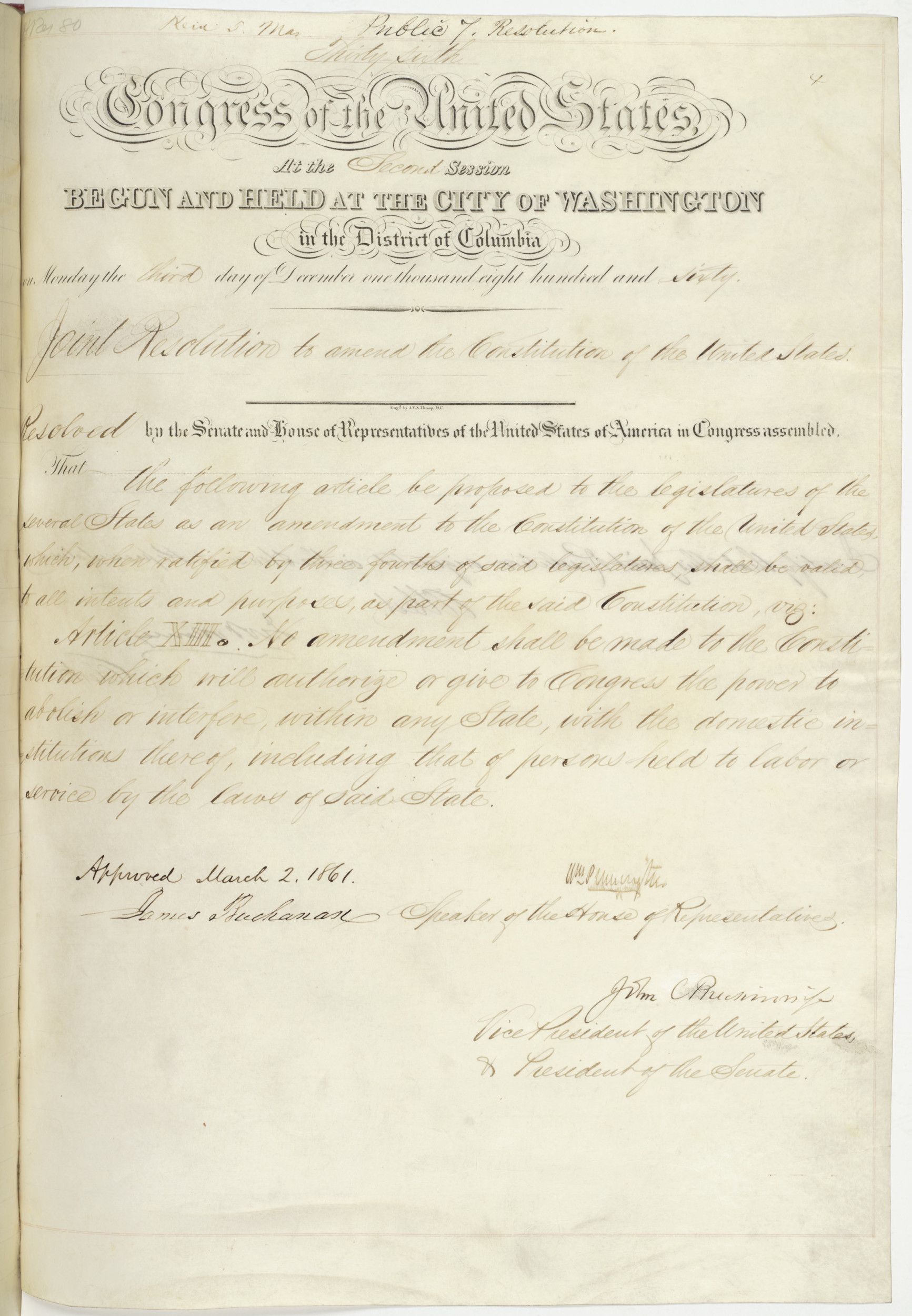

Document

Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

3/2/1861

As southern states began seceding during the winter of 1860–61, several compromises were proposed to hold the nation together. One was a constitutional amendment that would have prevented Congress from passing legislation interfering with a state’s “domestic institutions . . . including that of persons held to labor or service.” Amendment sponsors hoped its approval would keep border states in the Union and reassure southerners that Republicans opposed only the extension, not the existence, of slavery. Congress approved the amendment, but only two state legislatures ratified it."

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 4688370

Full Citation: Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery; 3/2/1861; General Records of the United States Government, . [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/proposed-thirteenth-amendment-regarding-the-abolition-of-slavery, April 24, 2024]Proposed Thirteenth Amendment Regarding the Abolition of Slavery

Page 2

Document

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

8/25/1864

"Mr. President, It is my Desire to be free," wrote Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln, 20 months after he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Writing from Belair, Maryland, she continued, "Will you please let me know if we are free."

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Transcript

Belair Aug 25th 1864Mr. President

It is my Desire to be free. to go to see my people on the eastern shore. my mistress wont let me you will please let me know if we are free. and what I can do. I write to you for advice. please send me word this[?] week. or as soon as possible. and oblidge.

Annie Davis

Belair Thaford

County. Mt D.

Belair Thaford

Cu[?]

This primary source comes from the Records of the Adjutant General's Office.

National Archives Identifier: 4662543

Full Citation: Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln; 8/25/1864; 1864 D-304; Letters Received, 1863-1888; Records of the Adjutant General's Office, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/letter-from-annie-davis-to-abraham-lincoln, April 24, 2024]Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

Document

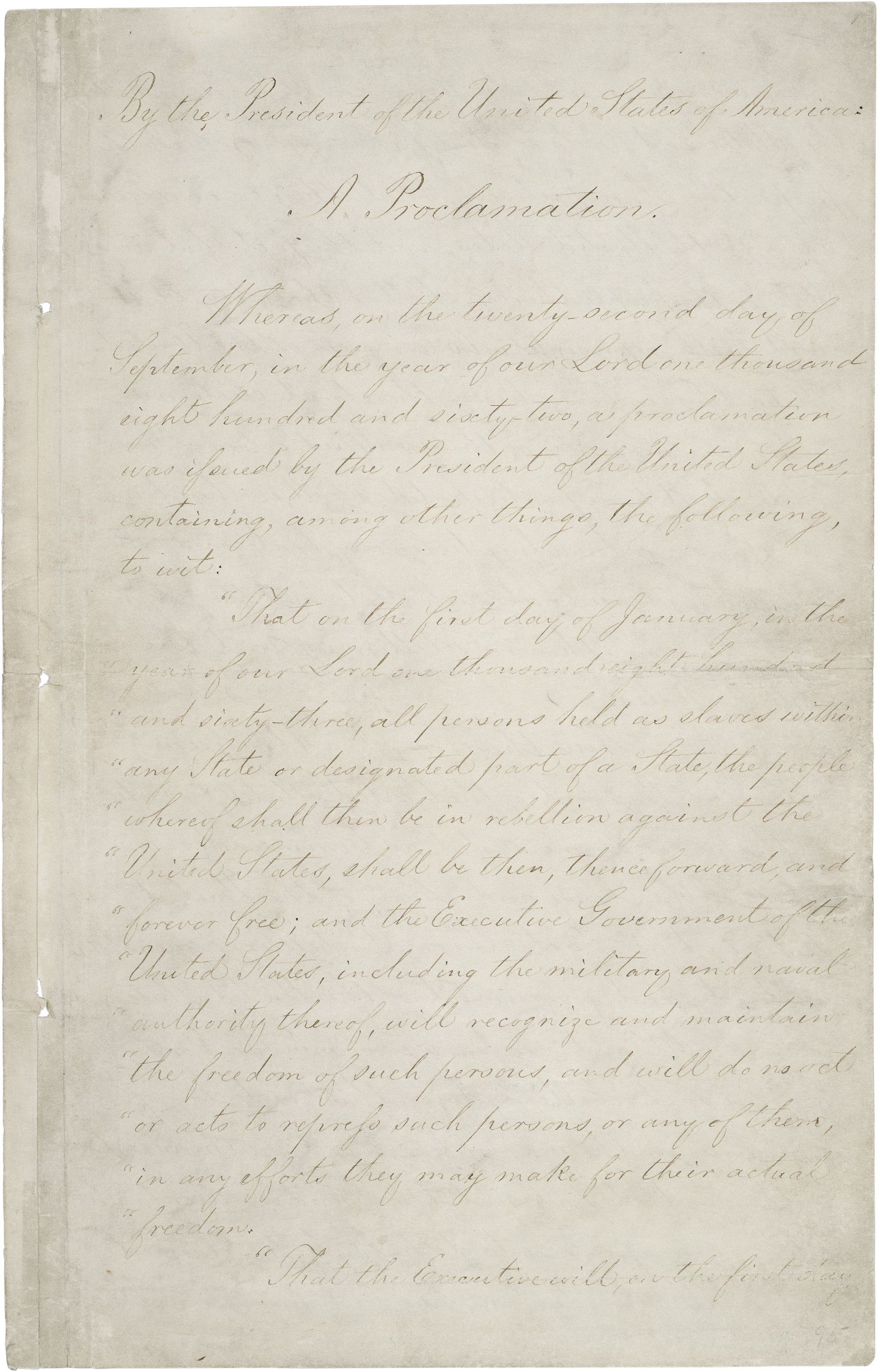

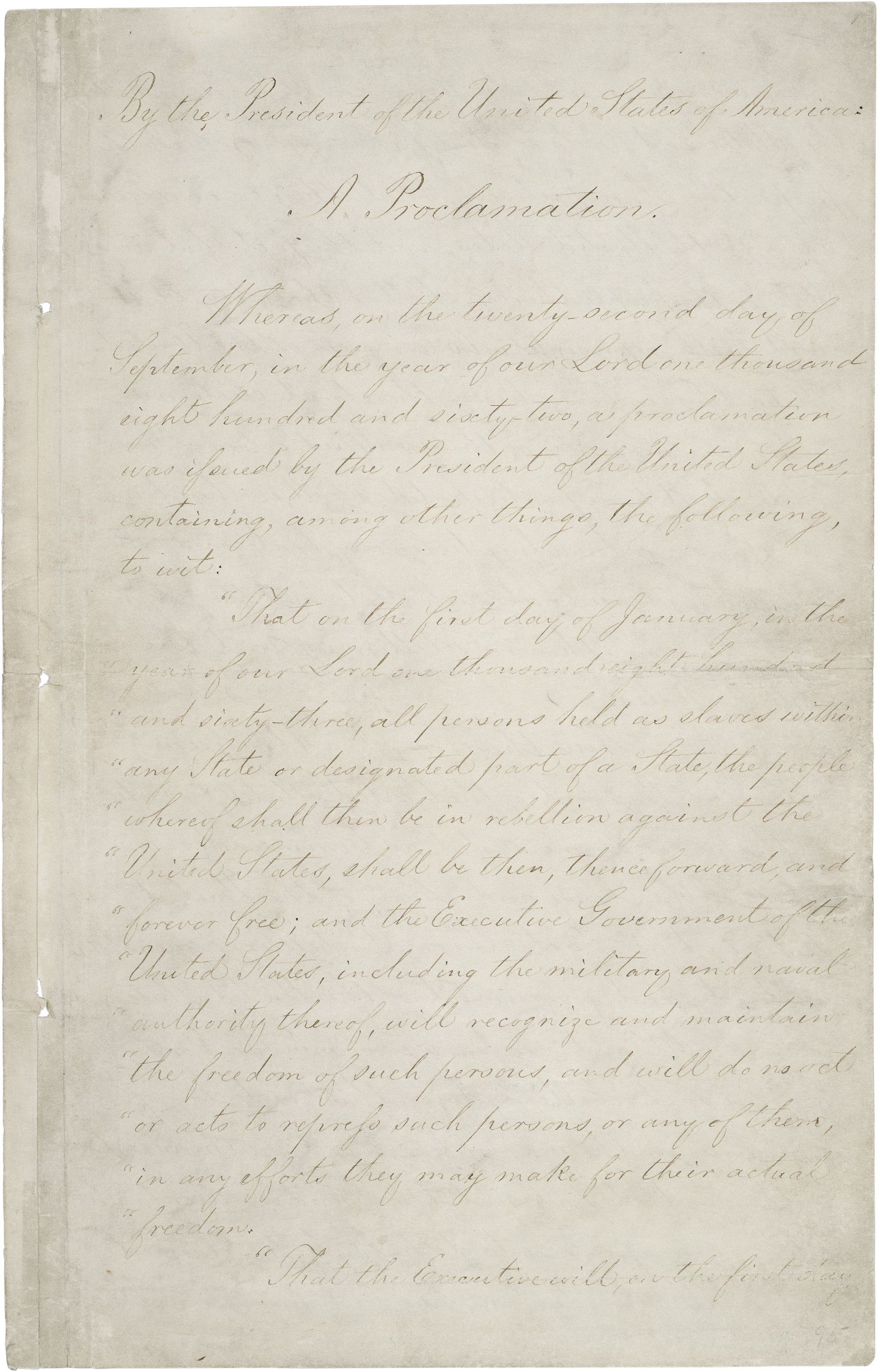

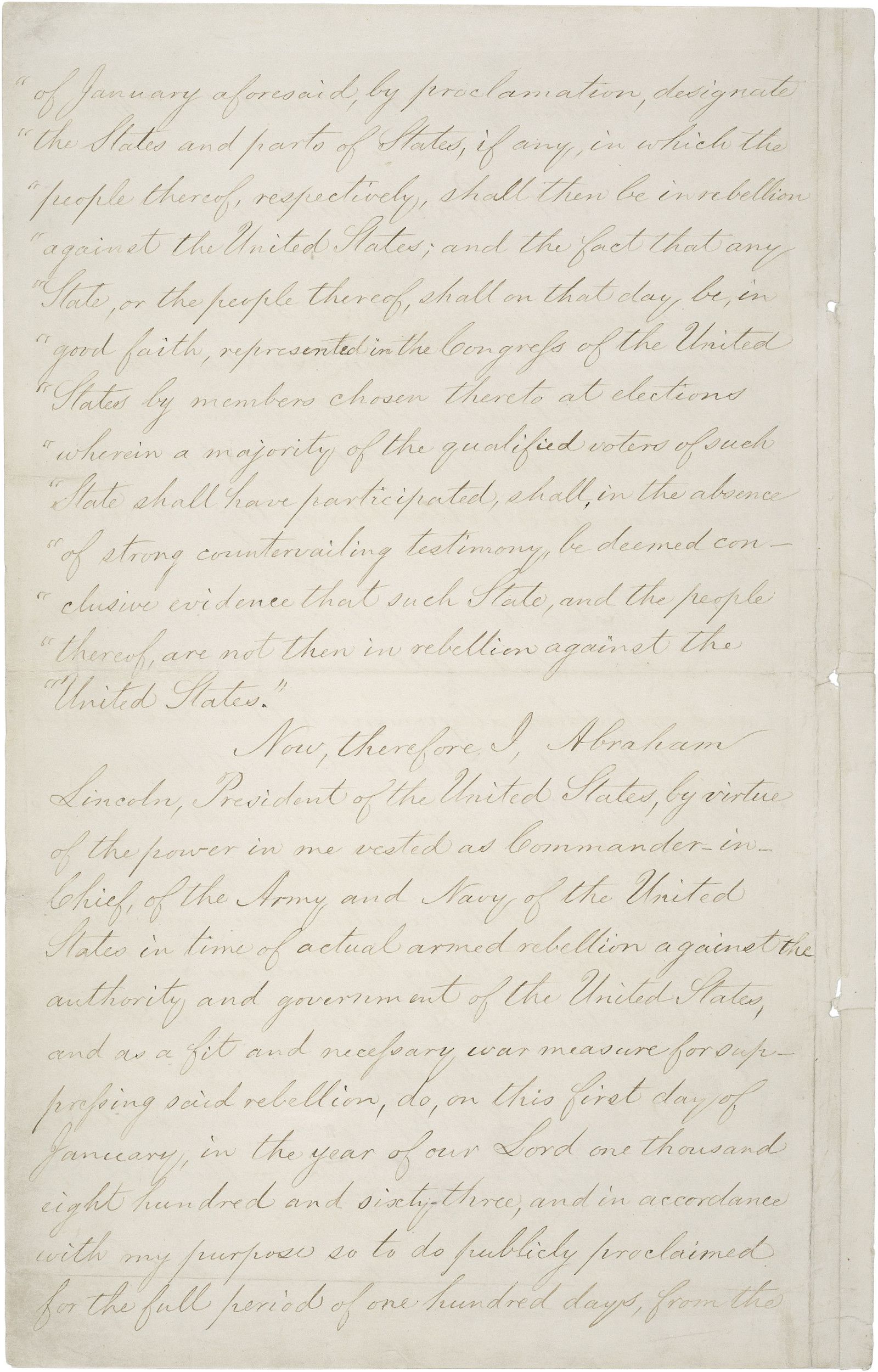

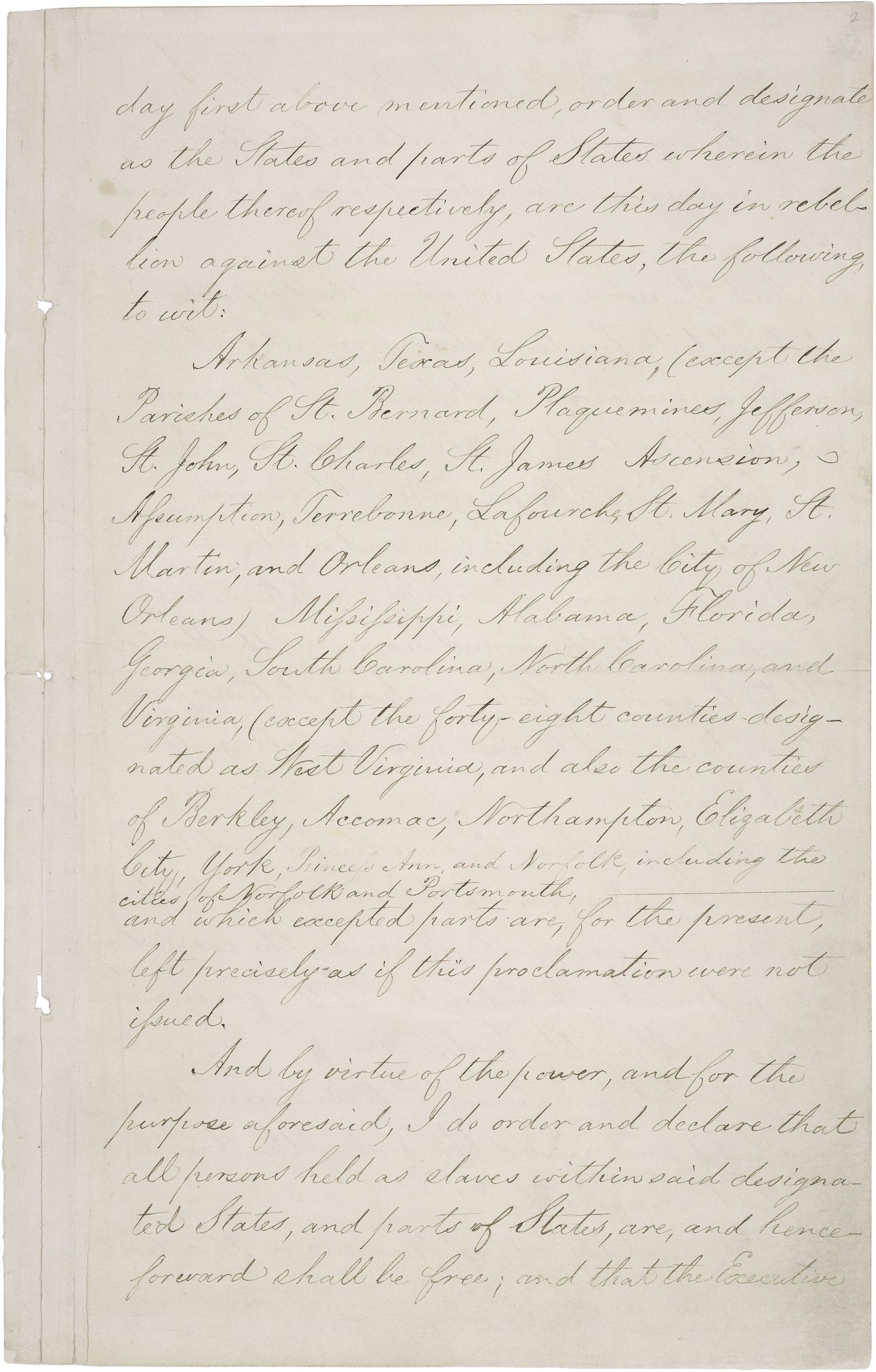

Emancipation Proclamation

1/1/1863

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, announcing, "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Initially, the Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that enslaved people in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free. One hundred days later, with the rebellion unabated, President issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Lincoln’s bold step to change the goals of the war was a military measure and came just a few days after the Union’s victory in the Battle of Antietam. With this Proclamation he hoped to inspire all Black people, and enslaved people in the Confederacy in particular, to support the Union cause and to keep England and France from giving political recognition and military aid to the Confederacy.

Because it was a military measure, however, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Union control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it did fundamentally transform the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of Federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of Black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 Black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

From the first days of the Civil War, enslaved people had acted to secure their own liberty. The Emancipation Proclamation confirmed their insistence that the war for the Union must become a war for freedom. It added moral force to the Union cause and strengthened the Union both militarily and politically. As a milestone along the road to slavery's final destruction, the Emancipation Proclamation has assumed a place among the great documents of human freedom.

Initially, the Civil War between North and South was fought by the North to prevent the secession of the Southern states and preserve the Union. Even though sectional conflicts over slavery had been a major cause of the war, ending slavery was not a goal of the war. That changed on September 22, 1862, when President Lincoln issued his Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation, which stated that enslaved people in those states or parts of states still in rebellion as of January 1, 1863, would be declared free. One hundred days later, with the rebellion unabated, President issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring "that all persons held as slaves" within the rebellious areas "are, and henceforward shall be free."

Lincoln’s bold step to change the goals of the war was a military measure and came just a few days after the Union’s victory in the Battle of Antietam. With this Proclamation he hoped to inspire all Black people, and enslaved people in the Confederacy in particular, to support the Union cause and to keep England and France from giving political recognition and military aid to the Confederacy.

Because it was a military measure, however, the Emancipation Proclamation was limited in many ways. It applied only to states that had seceded from the Union, leaving slavery untouched in the loyal border states. It also expressly exempted parts of the Confederacy that had already come under Union control. Most important, the freedom it promised depended upon Union military victory.

Although the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation, it did fundamentally transform the character of the war. After January 1, 1863, every advance of Federal troops expanded the domain of freedom. Moreover, the Proclamation announced the acceptance of Black men into the Union Army and Navy, enabling the liberated to become liberators. By the end of the war, almost 200,000 Black soldiers and sailors had fought for the Union and freedom.

From the first days of the Civil War, enslaved people had acted to secure their own liberty. The Emancipation Proclamation confirmed their insistence that the war for the Union must become a war for freedom. It added moral force to the Union cause and strengthened the Union both militarily and politically. As a milestone along the road to slavery's final destruction, the Emancipation Proclamation has assumed a place among the great documents of human freedom.

Transcript

By the President of the United States of America:A Proclamation.

Whereas, on the twenty-second day of September, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two, a proclamation was issued by the President of the United States, containing, among other things, the following, to wit:

"That on the first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, all persons held as slaves within any State or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free; and the Executive Government of the United States, including the military and naval authority thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of such persons, and will do no act or acts to repress such persons, or any of them, in any efforts they may make for their actual freedom.

"That the Executive will, on the first day of January aforesaid, by proclamation, designate the States and parts of States, if any, in which the people thereof, respectively, shall then be in rebellion against the United States; and the fact that any State, or the people thereof, shall on that day be, in good faith, represented in the Congress of the United States by members chosen thereto at elections wherein a majority of the qualified voters of such State shall have participated, shall, in the absence of strong countervailing testimony, be deemed conclusive evidence that such State, and the people thereof, are not then in rebellion against the United States."

Now, therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, by virtue of the power in me vested as Commander-in-Chief, of the Army and Navy of the United States in time of actual armed rebellion against the authority and government of the United States, and as a fit and necessary war measure for suppressing said rebellion, do, on this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-three, and in accordance with my purpose so to do publicly proclaimed for the full period of one hundred days, from the day first above mentioned, order and designate as the States and parts of States wherein the people thereof respectively, are this day in rebellion against the United States, the following, to wit:

Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, (except the Parishes of St. Bernard, Plaquemines, Jefferson, St. John, St. Charles, St. James Ascension, Assumption, Terrebonne, Lafourche, St. Mary, St. Martin, and Orleans, including the City of New Orleans) Mississippi, Alabama, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, and Virginia, (except the forty-eight counties designated as West Virginia, and also the counties of Berkley, Accomac, Northampton, Elizabeth City, York, Princess Ann, and Norfolk, including the cities of Norfolk and Portsmouth[)], and which excepted parts, are for the present, left precisely as if this proclamation were not issued.

And by virtue of the power, and for the purpose aforesaid, I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.

And I hereby enjoin upon the people so declared to be free to abstain from all violence, unless in necessary self-defence; and I recommend to them that, in all cases when allowed, they labor faithfully for reasonable wages.

And I further declare and make known, that such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations, and other places, and to man vessels of all sorts in said service.

And upon this act, sincerely believed to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind, and the gracious favor of Almighty God.

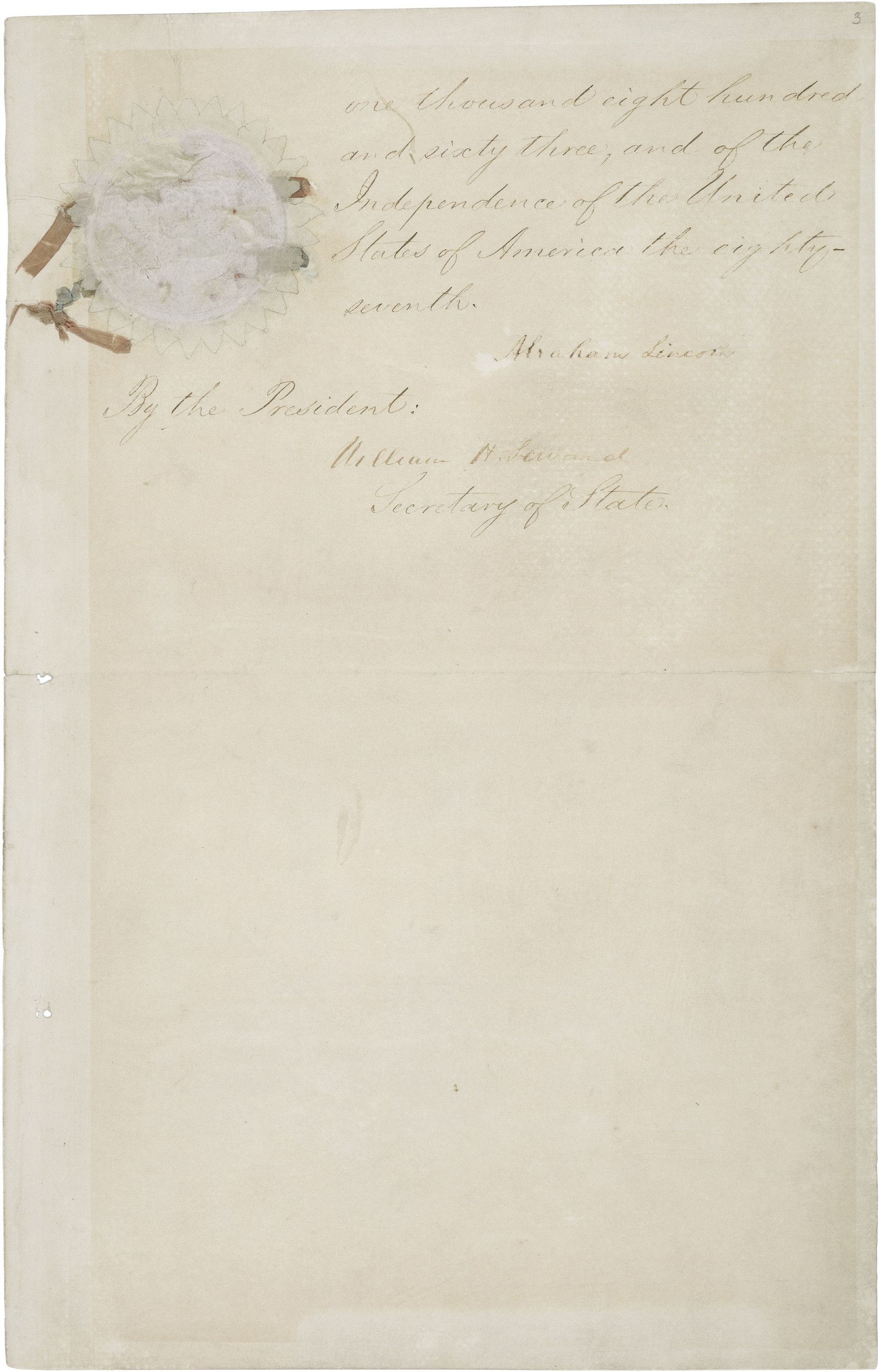

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Done at the City of Washington, this first day of January, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty three, and of the Independence of the United States of America the eighty-seventh.

By the President: ABRAHAM LINCOLN

WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 299998

Full Citation: Emancipation Proclamation; 1/1/1863; Presidential Proclamations, 1791 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/emancipation-proclamation, April 24, 2024]Emancipation Proclamation

Page 1

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 2

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 3

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 4

Emancipation Proclamation

Page 5

Document

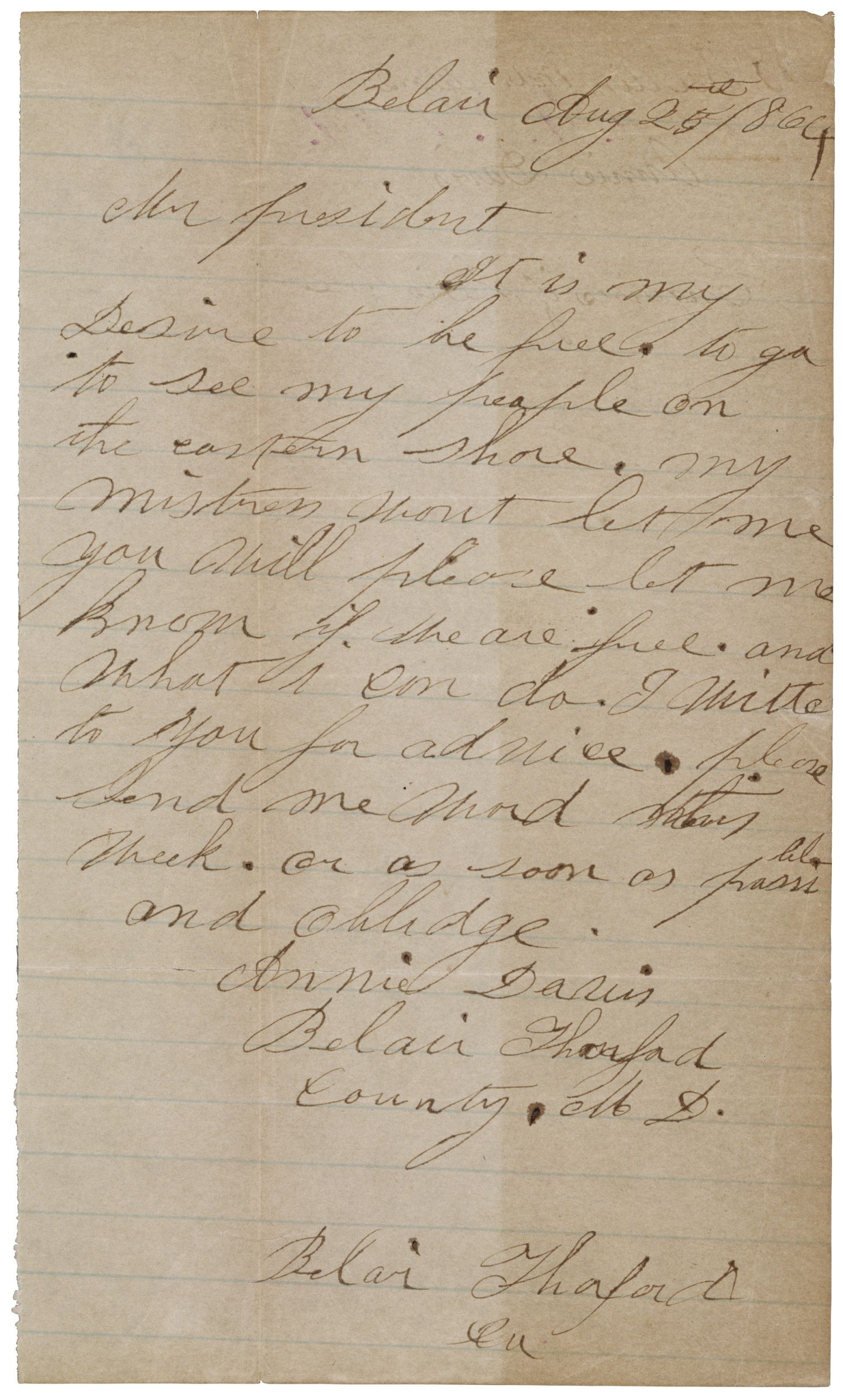

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

8/25/1864

"Mr. President, It is my Desire to be free," wrote Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln, 20 months after he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Writing from Belair, Maryland, she continued, "Will you please let me know if we are free."

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Transcript

Belair Aug 25th 1864Mr. President

It is my Desire to be free. to go to see my people on the eastern shore. my mistress wont let me you will please let me know if we are free. and what I can do. I write to you for advice. please send me word this[?] week. or as soon as possible. and oblidge.

Annie Davis

Belair Thaford

County. Mt D.

Belair Thaford

Cu[?]

This primary source comes from the Records of the Adjutant General's Office.

National Archives Identifier: 4662543

Full Citation: Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln; 8/25/1864; 1864 D-304; Letters Received, 1863-1888; Records of the Adjutant General's Office, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/letter-from-annie-davis-to-abraham-lincoln, April 24, 2024]Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

Document

Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

8/25/1864

"Mr. President, It is my Desire to be free," wrote Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln, 20 months after he issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Writing from Belair, Maryland, she continued, "Will you please let me know if we are free."

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Although there is no record of Lincoln ever responding, had he, his answer would have been "No, you are not free." The Emancipation Proclamation affected only those parts that were in rebellion against the United States on the date it was issued, January 1, 1863. The slaveholding border states of Delaware, Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri were thus exempt from the Proclamation. However, in November 1864 the Maryland state constitution was rewritten. The new version abolished slavery, and Annie Davis was free.

Text adapted from “It is My Desire to be Free: Annie Davis’s Letter to Abraham Lincoln and Winslow Homer’s Painting A Visit from the Old Mistress” in the May/June 2010 National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) publication Social Education.

Transcript

Belair Aug 25th 1864Mr. President

It is my Desire to be free. to go to see my people on the eastern shore. my mistress wont let me you will please let me know if we are free. and what I can do. I write to you for advice. please send me word this[?] week. or as soon as possible. and oblidge.

Annie Davis

Belair Thaford

County. Mt D.

Belair Thaford

Cu[?]

This primary source comes from the Records of the Adjutant General's Office.

National Archives Identifier: 4662543

Full Citation: Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln; 8/25/1864; 1864 D-304; Letters Received, 1863-1888; Records of the Adjutant General's Office, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/letter-from-annie-davis-to-abraham-lincoln, April 24, 2024]Letter from Annie Davis to Abraham Lincoln

Page 2

Document

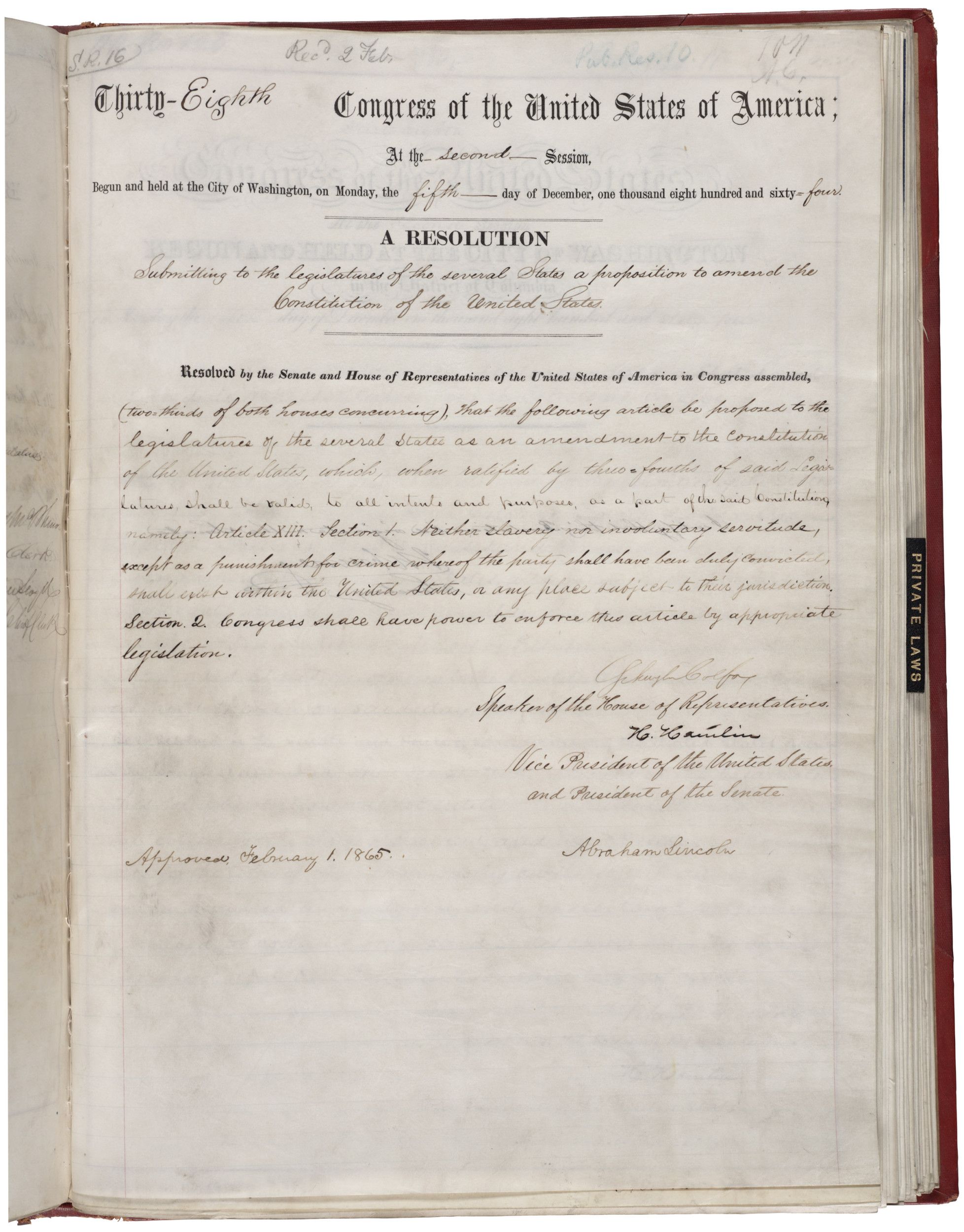

Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

1/31/1865

This is a draft of a joint resolution proposing the 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution that started in the Senate. A joint resolution is a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification. This particular resolution became the 13th Amendment, ending slavery in the United States in 1865.

In 1863, President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Nonetheless, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation since it only applied to areas of the Confederacy currently in a state of rebellion (and not even to the loyal “border states” that remained in the Union). Lincoln recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

The 13th Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War before the Southern states had been restored to the Union, and should have easily passed in Congress. However, though the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through Congress. He insisted that passage of the 13th Amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming 1864 Presidential election. His efforts met with success when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119–56.

On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. The necessary number of states (three-fourths) ratified it by December 6, 1865. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery. The 13th Amendment, along with the 14th and 15th, is one of the trio of Civil War amendments that greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans.

In 1863, President Lincoln had issued the Emancipation Proclamation declaring “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States, shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.” Nonetheless, the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery in the nation since it only applied to areas of the Confederacy currently in a state of rebellion (and not even to the loyal “border states” that remained in the Union). Lincoln recognized that the Emancipation Proclamation would have to be followed by a constitutional amendment in order to guarantee the abolishment of slavery.

The 13th Amendment was passed at the end of the Civil War before the Southern states had been restored to the Union, and should have easily passed in Congress. However, though the Senate passed it in April 1864, the House initially did not. At that point, Lincoln took an active role to ensure passage through Congress. He insisted that passage of the 13th Amendment be added to the Republican Party platform for the upcoming 1864 Presidential election. His efforts met with success when the House passed the bill in January 1865 with a vote of 119–56.

On February 1, 1865, President Abraham Lincoln approved the Joint Resolution of Congress submitting the proposed amendment to the state legislatures. The necessary number of states (three-fourths) ratified it by December 6, 1865. The 13th Amendment to the United States Constitution provides that "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

With the adoption of the 13th Amendment, the United States found a final constitutional solution to the issue of slavery. The 13th Amendment, along with the 14th and 15th, is one of the trio of Civil War amendments that greatly expanded the civil rights of Americans.

Transcript

Thirty-Eighth Congress of the United StatesAt the Second Session

Begun and held at the City of Washington, on Monday, the fifth day of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-four

A Resolution

Submitting to the legislatures of the several States a proposition to amend the Constitution of the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled,

(two-thirds of both houses concurring), that the following article be proposed to the legislatures of the several states as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three-fourths of said Legislatures shall be

valid, to all intents and purposes, as part of the said Constitution, namely: Article XIII. Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction. Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Schuyler Colfax

Speaker of the House of Representatives

Hannibal Hamlin

Vice President of the United States

and President of the Senate

Approved February 1, 1865 Abraham Lincoln

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 1408764

Full Citation: Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; 1/31/1865; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/thirteenth-amendment, April 24, 2024]Joint Resolution Proposing the Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 2