The Long Struggle for LGBTQ+ Civil Rights

Finding a Sequence

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

The struggle for LGBTQ+ civil rights has a long history and involved many people. Look at each primary source below and analyze it — click on the orange "open in new window" icon to see each one more closely (and learn more about it). Then put the sources in chronological order so you get a sense of the scope and depth of the civil rights issues people confronted and worked to change over the last three-quarters of a century.As you look at each historical source, think about (or write down) the issues presented, how people tried to change things, and the successes of the movement.

Keep in mind that some of these sources use words that were common at the time but are now considered outdated and inappropriate, such as "homosexual" and "Negro," rather than terms used today, like "gay" and "Black."

Class:

Worksheet

The Long Struggle for LGBTQ+ Civil Rights

Finding a Sequence

Examine the documents in this activity. Put the corresponding document numbers in order using the list below. Write your conclusion response in the space provided.Activity Element

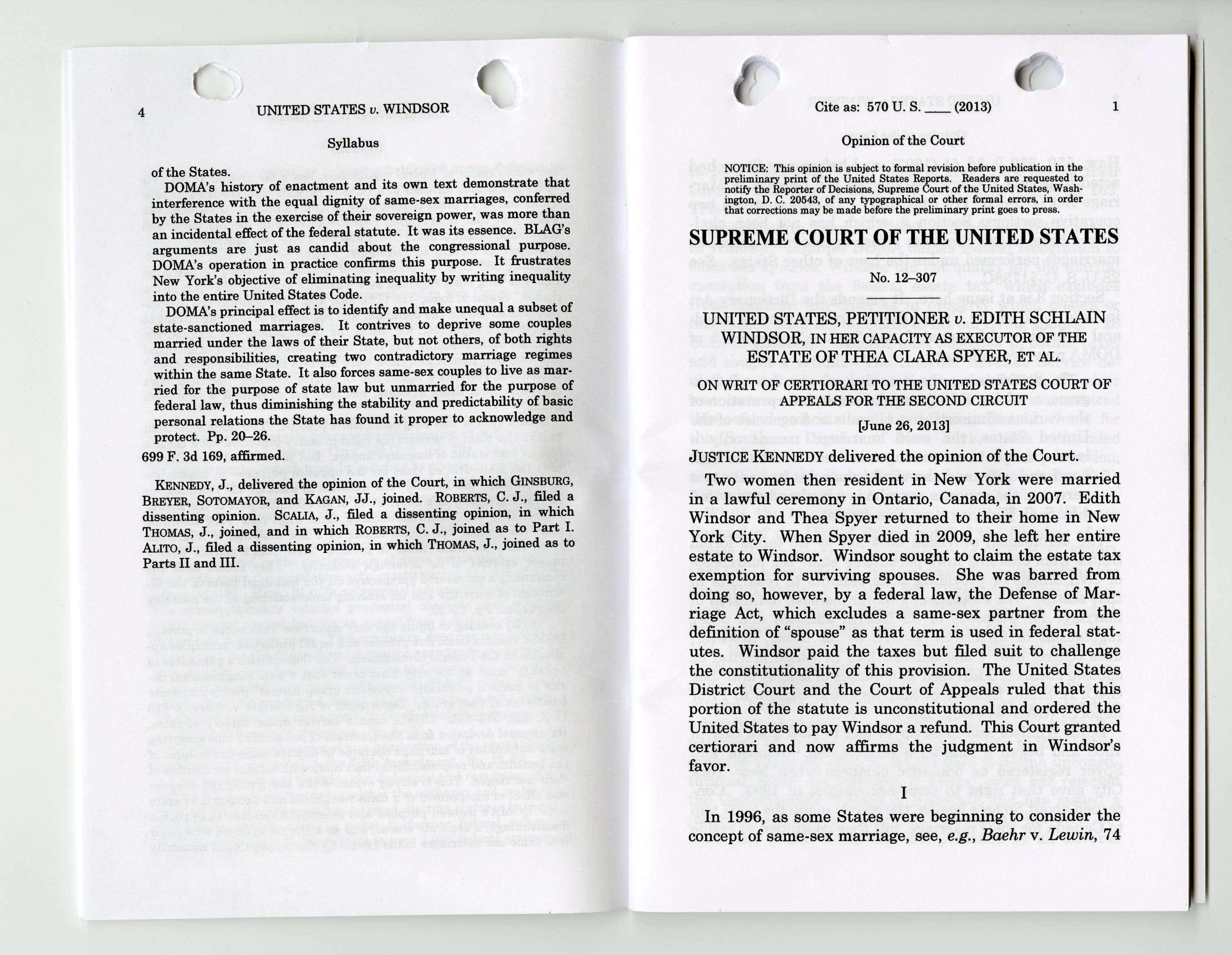

Opinion in U.S. v. Edith Windsor

Page 1

Activity Element

President Barack Obama Greets Frank Kameny in the Oval Office

Page 1

Activity Element

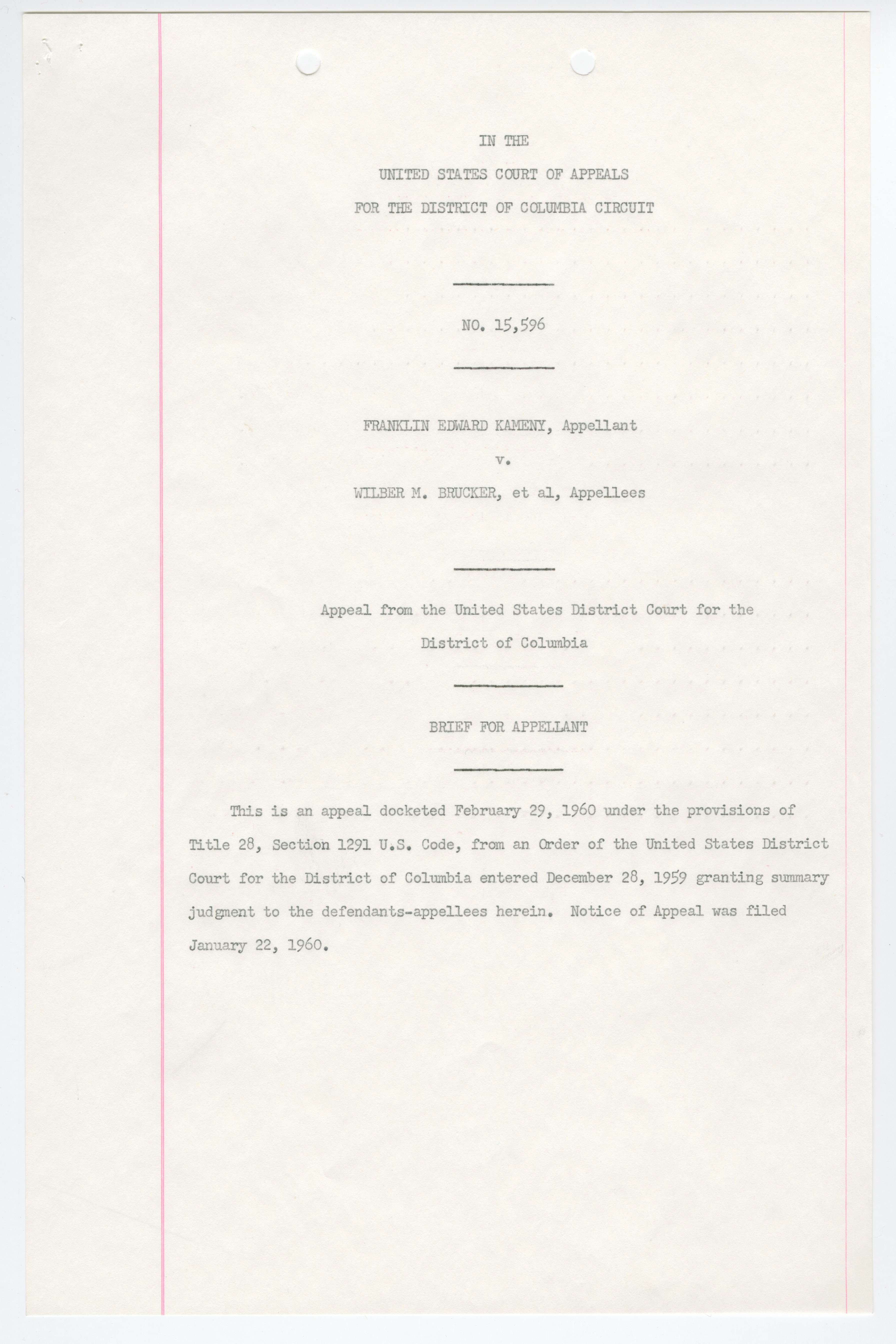

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 1

Activity Element

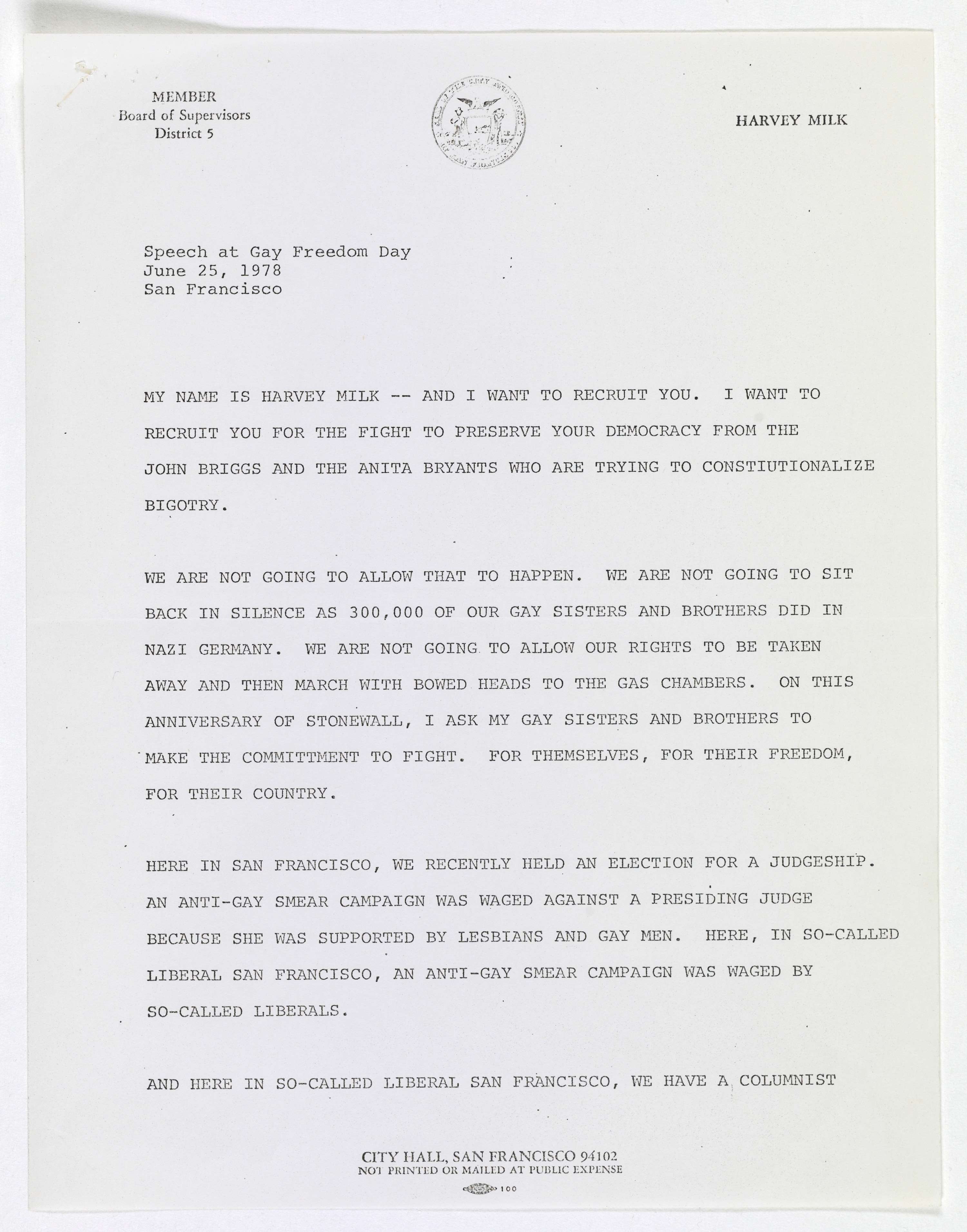

Harvey Milk`s Speech at San Francisco`s Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 1

Activity Element

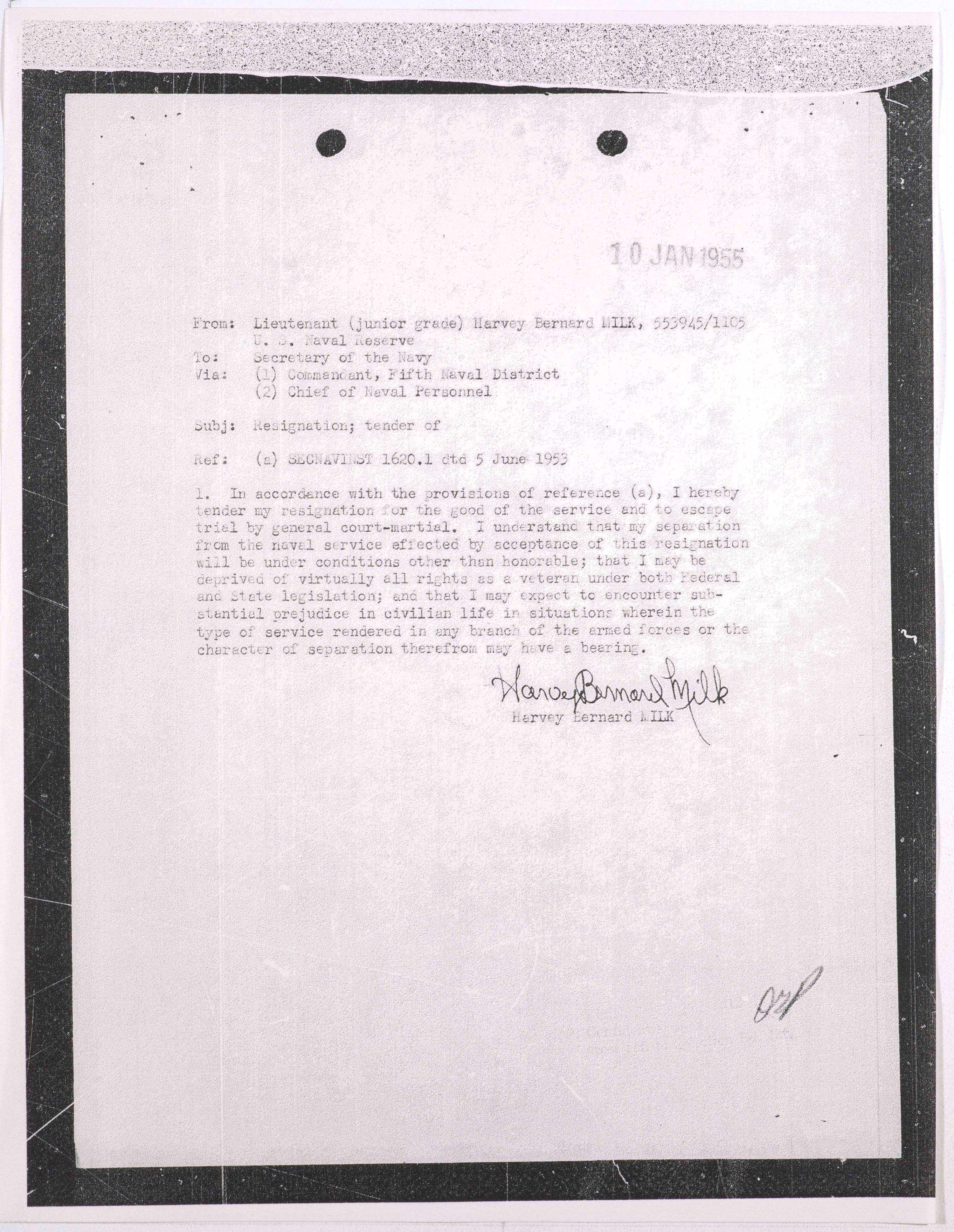

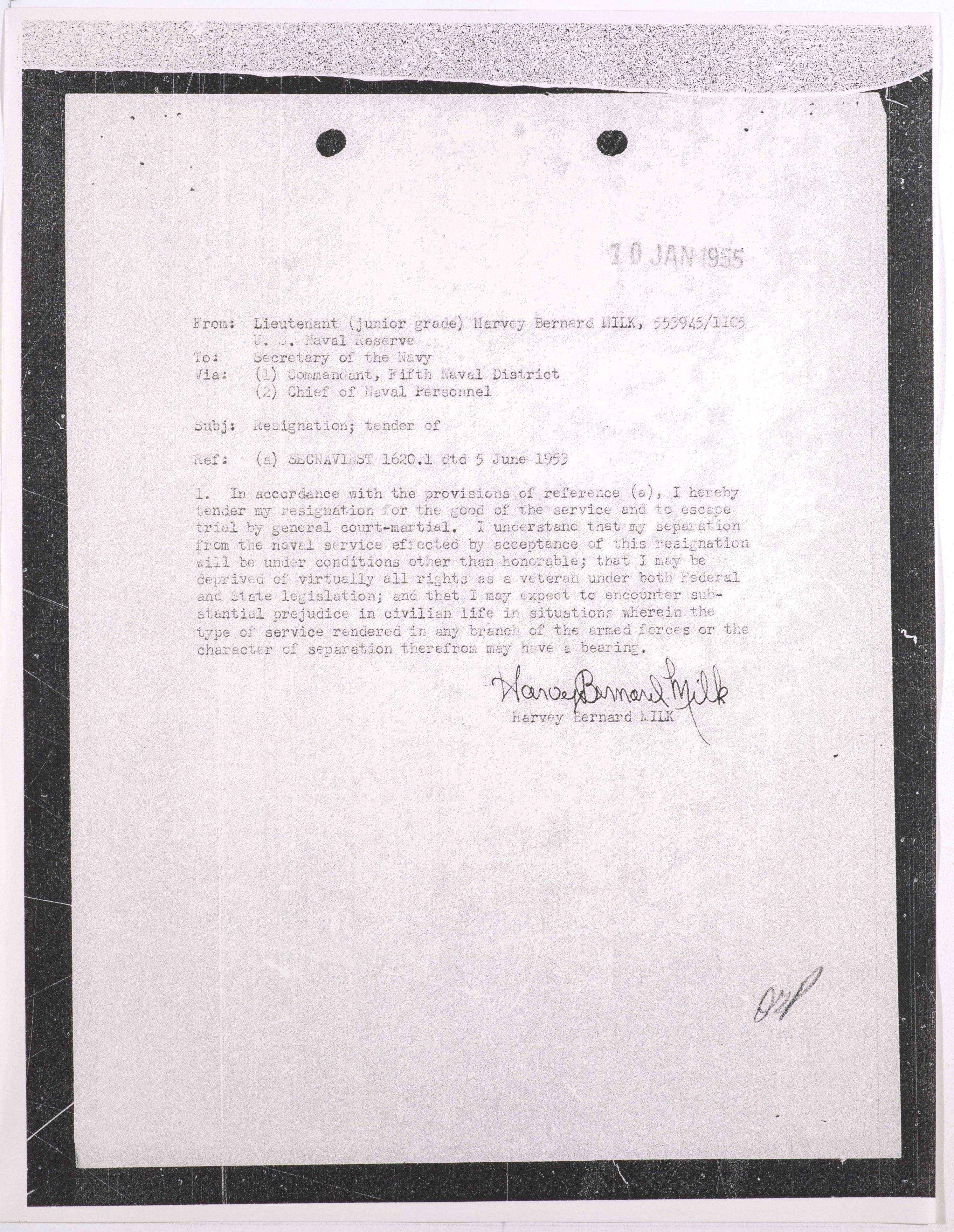

Tender of Resignation by Harvey B. Milk

Page 1

Activity Element

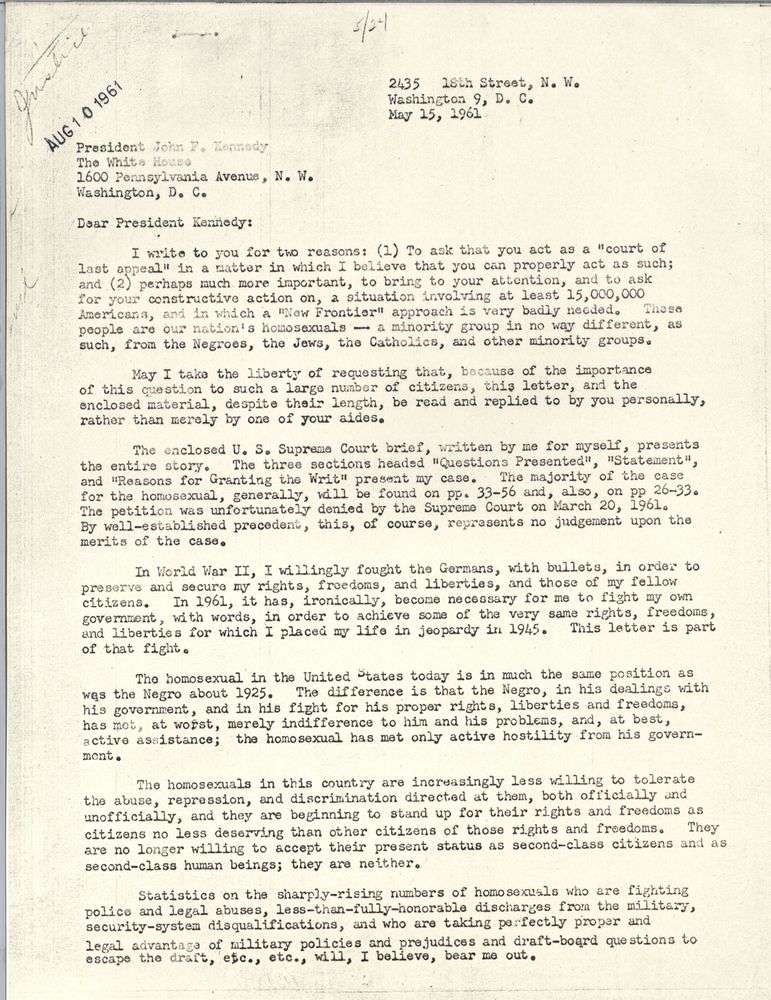

Letter from Franklin E. Kameny to President John F. Kennedy

Page 1

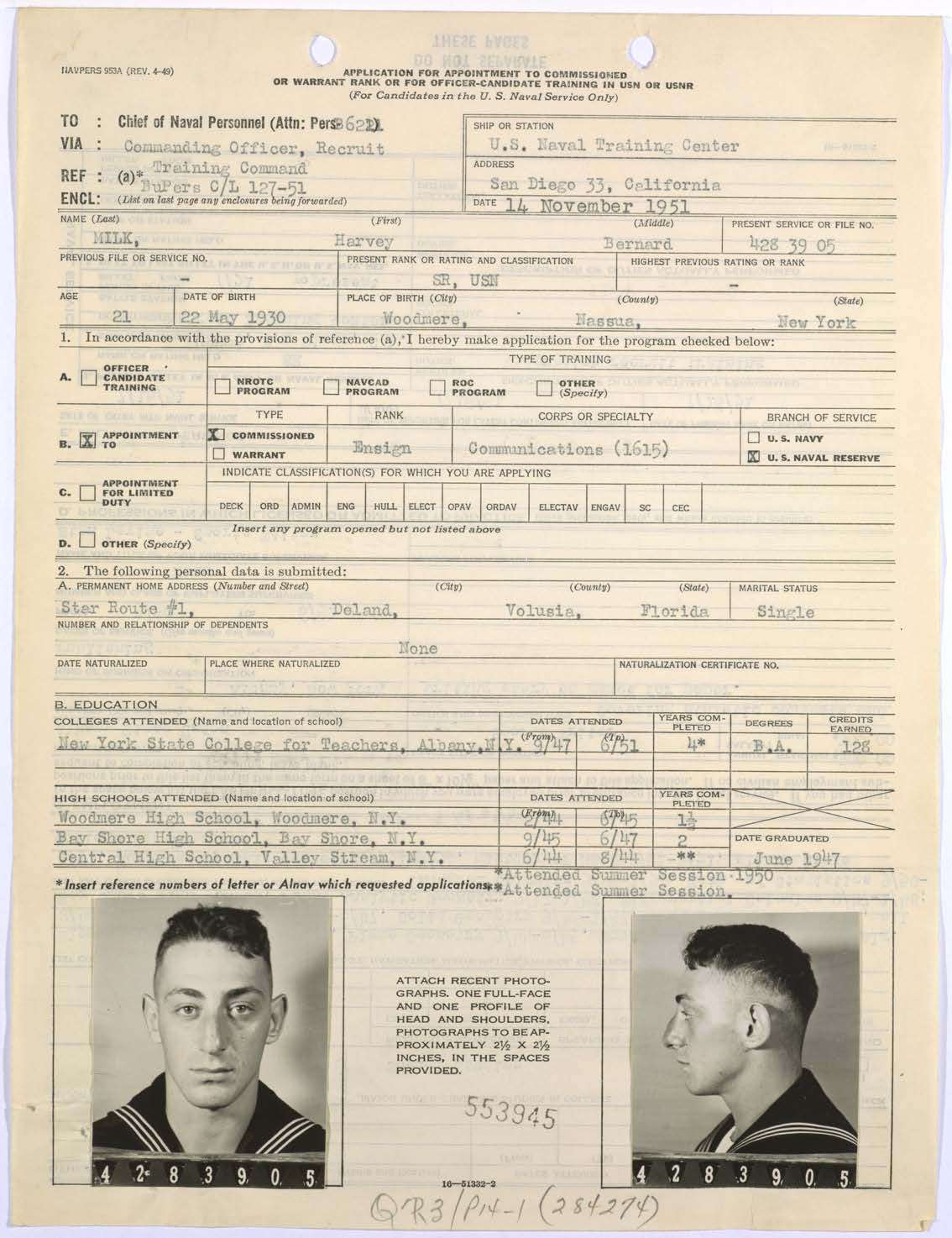

Activity Element

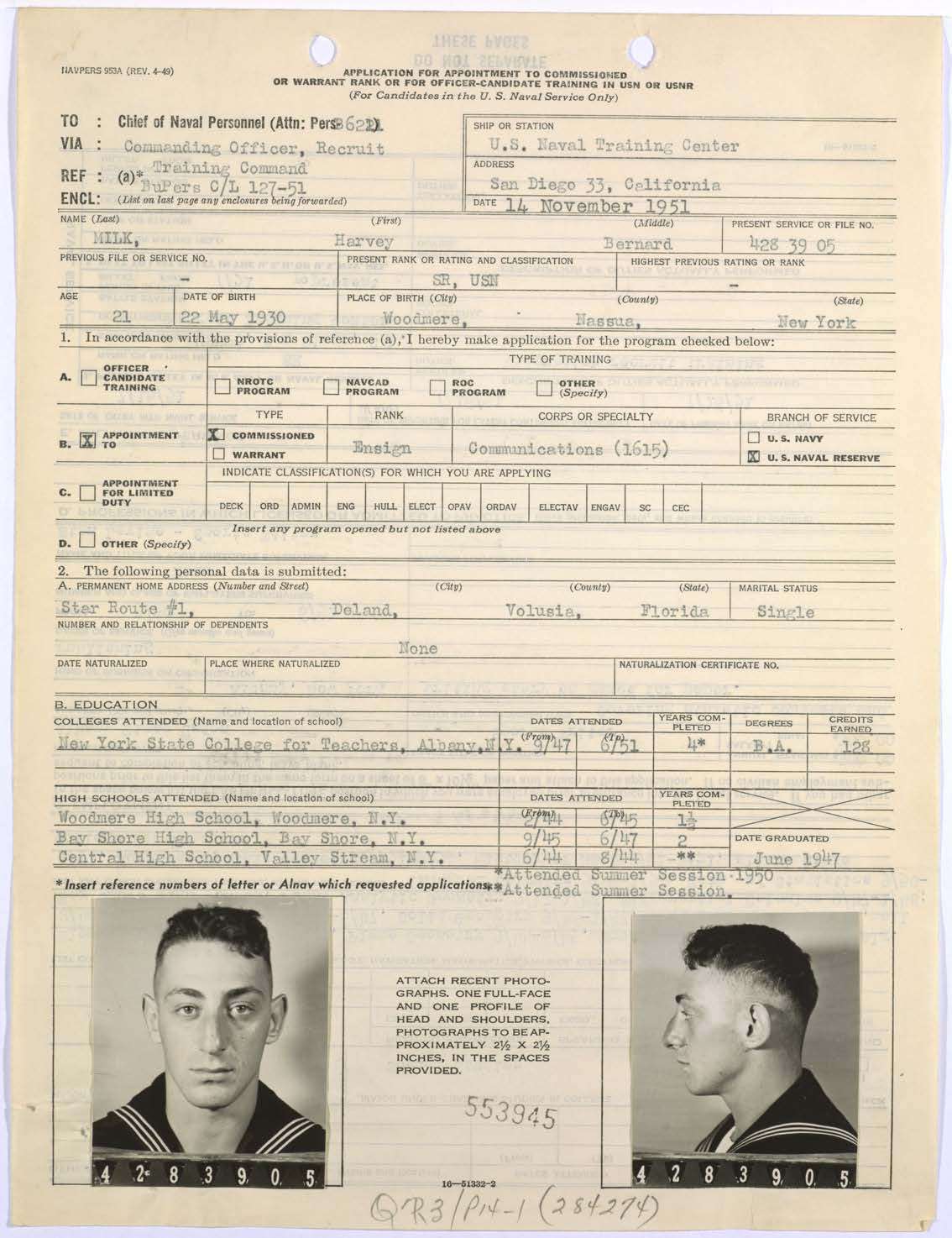

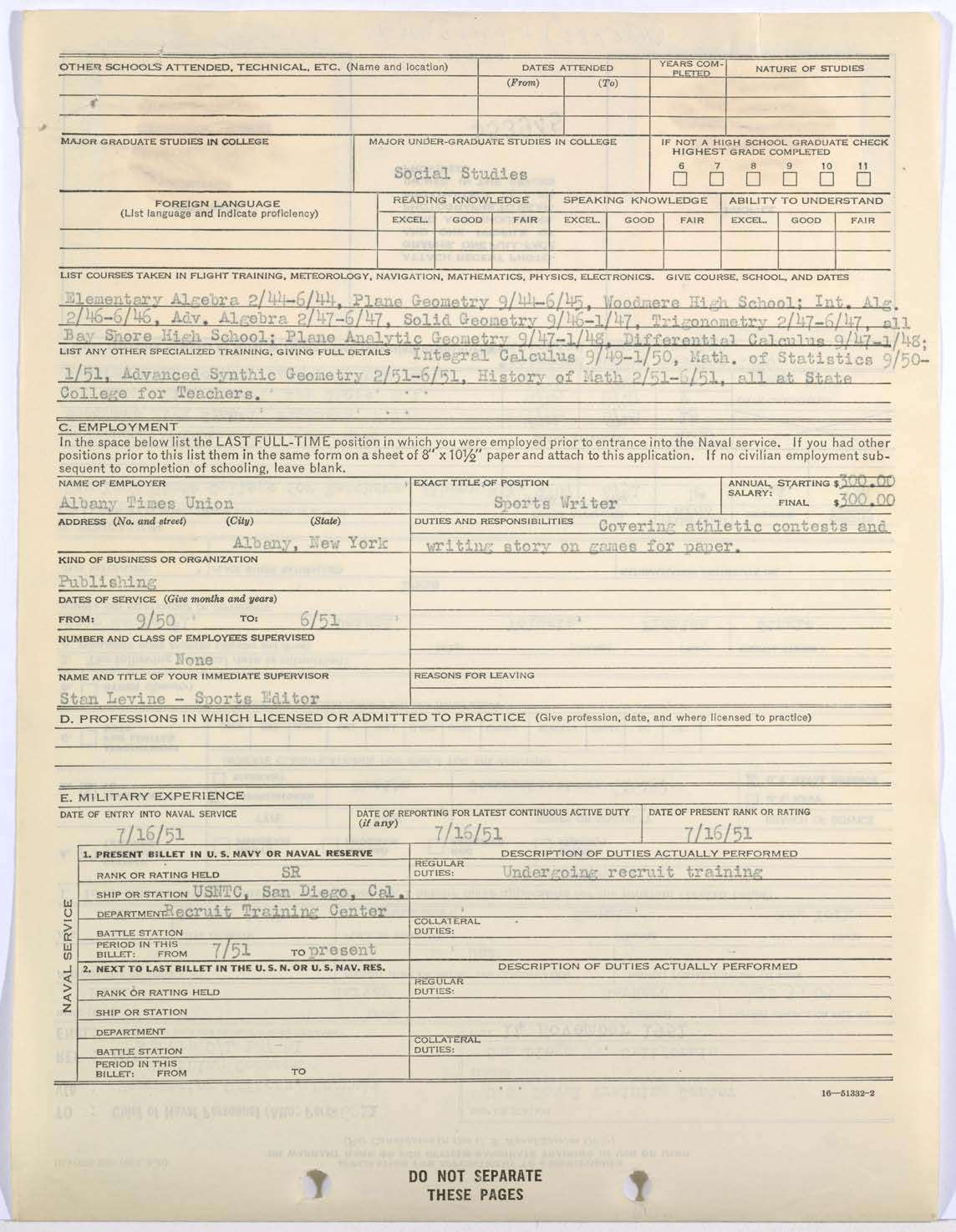

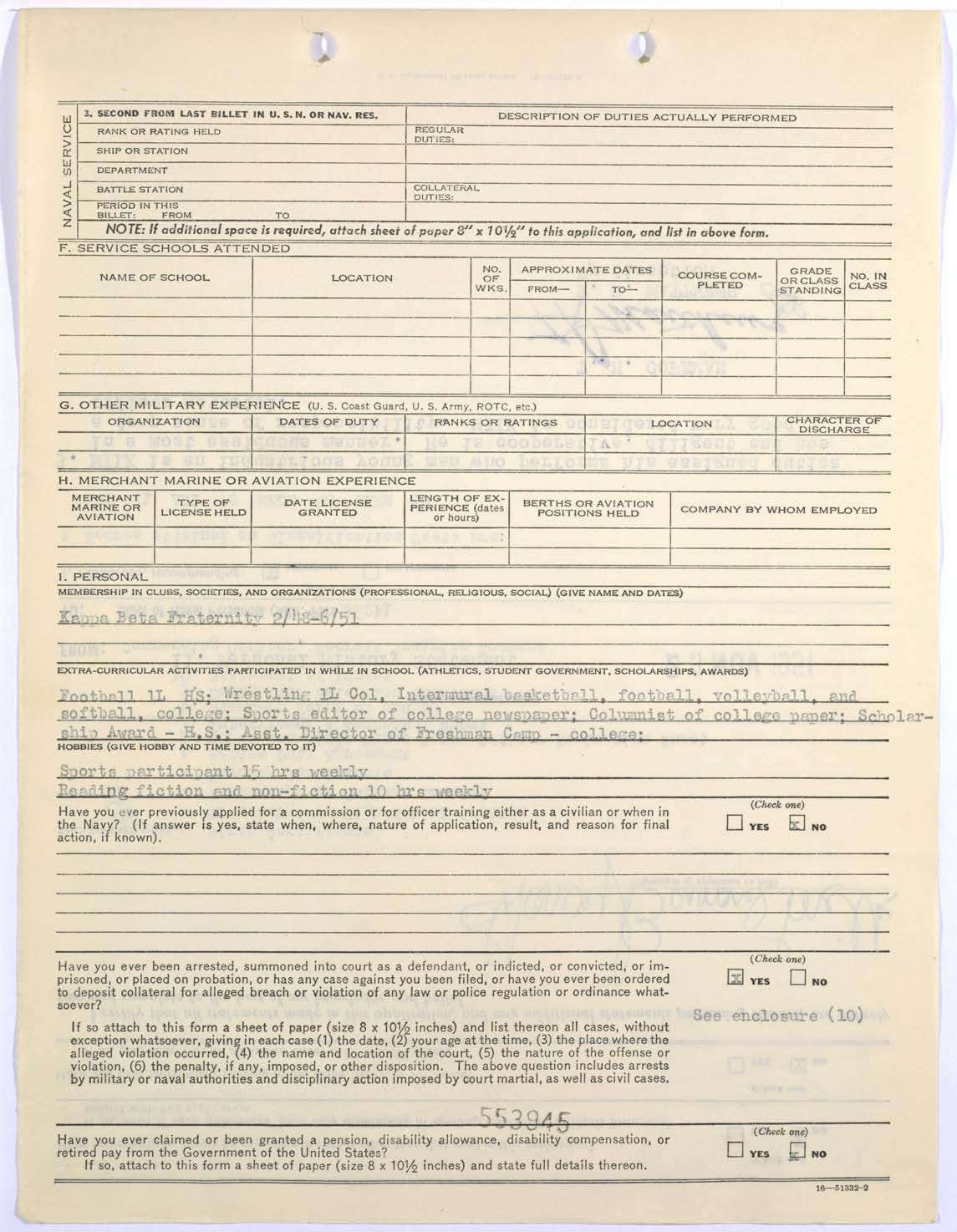

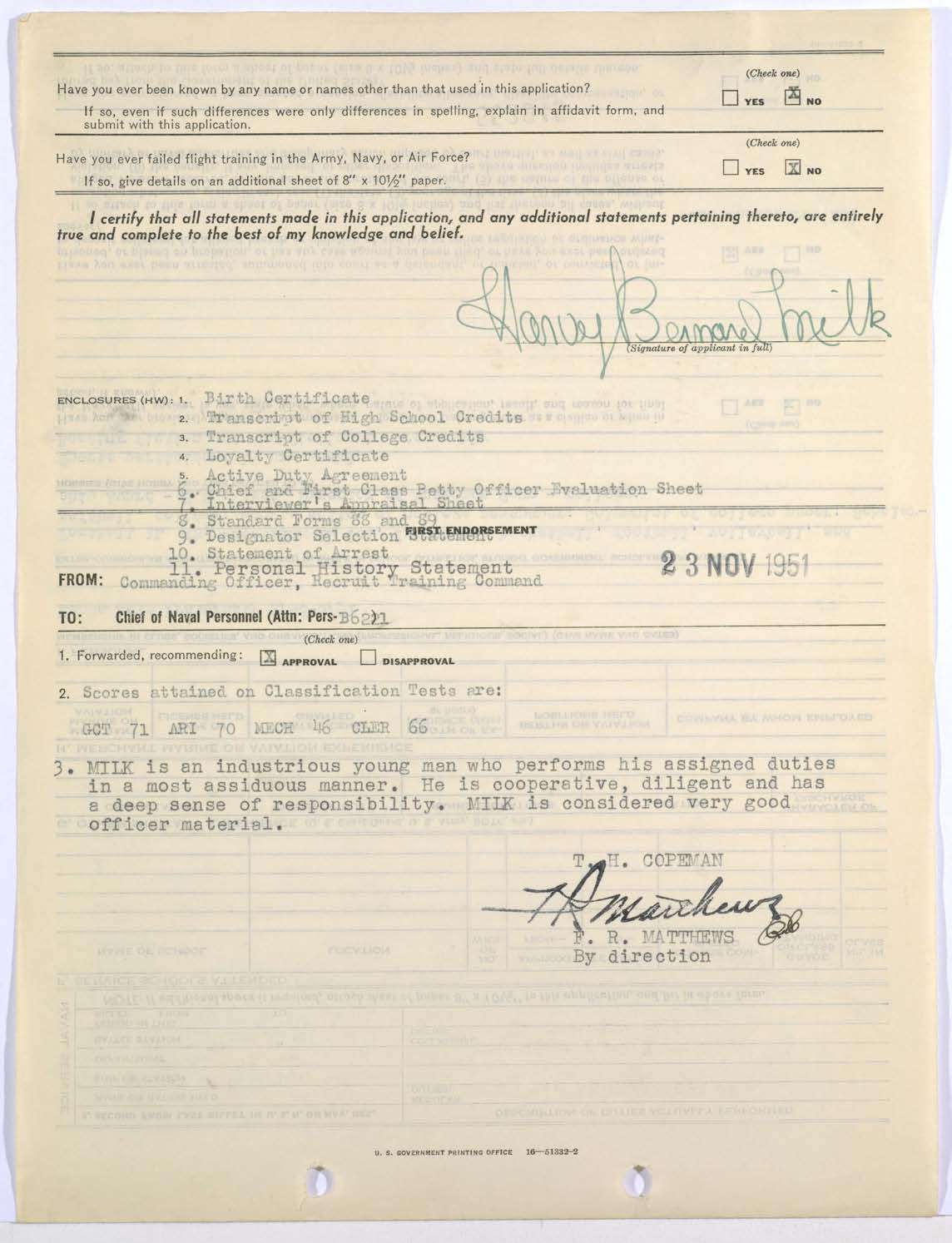

Harvey Milk`s Application for Appointment to Commissioned Rank of Ensign

Page 1

Activity Element

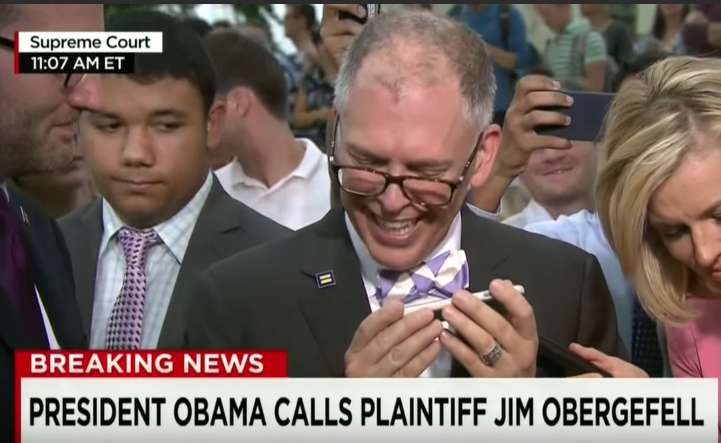

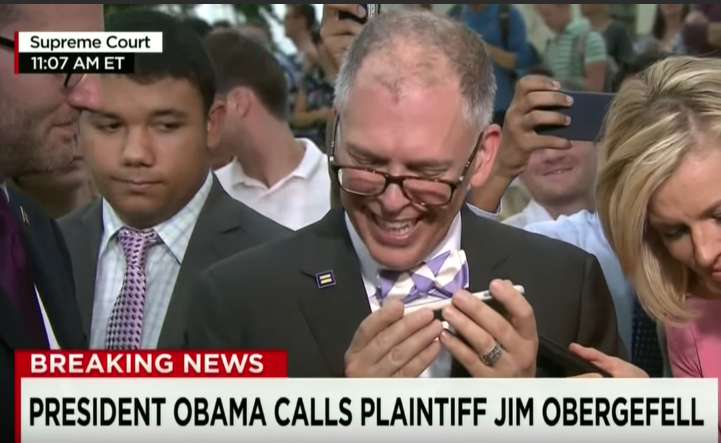

“Hi, is this Jim?”

Page 1

Activity Element

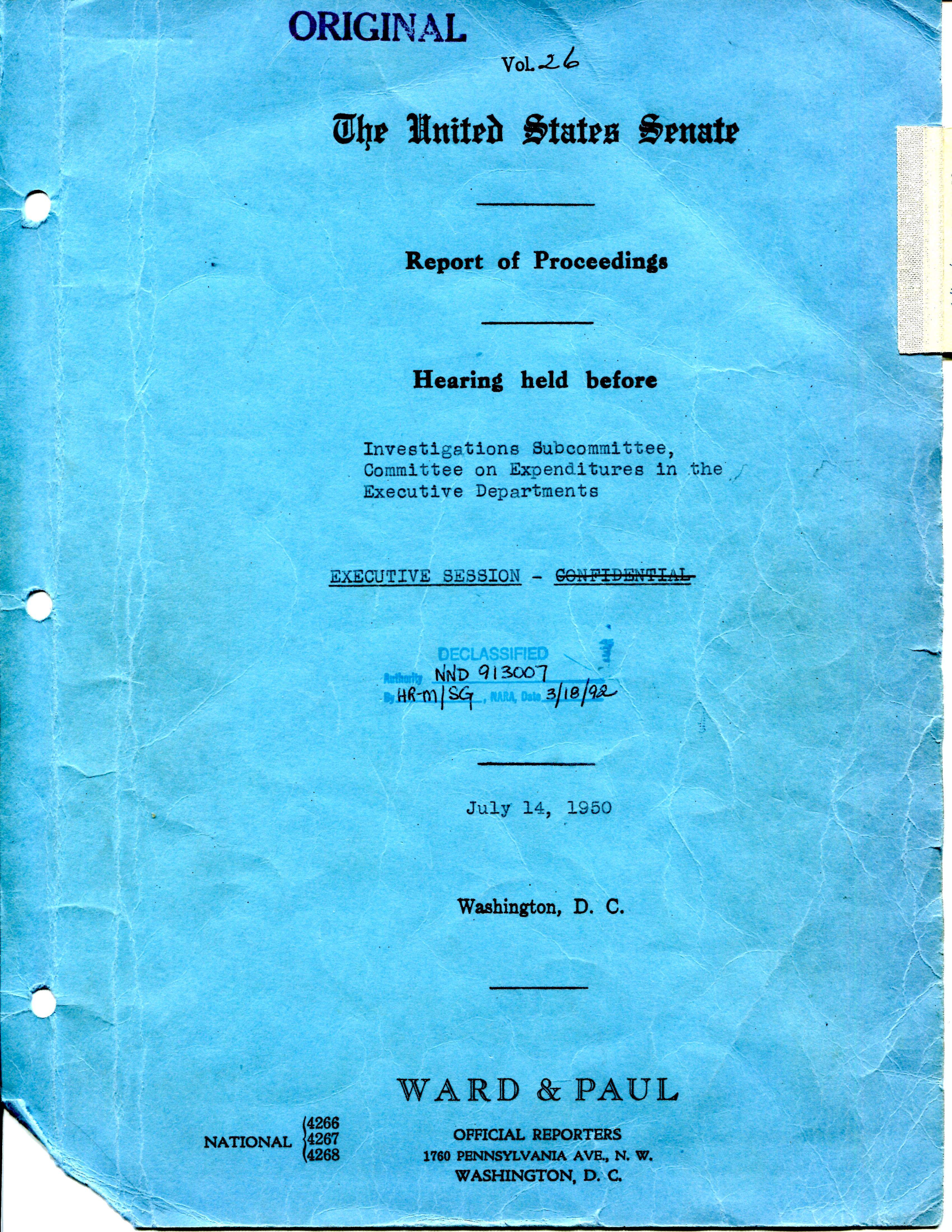

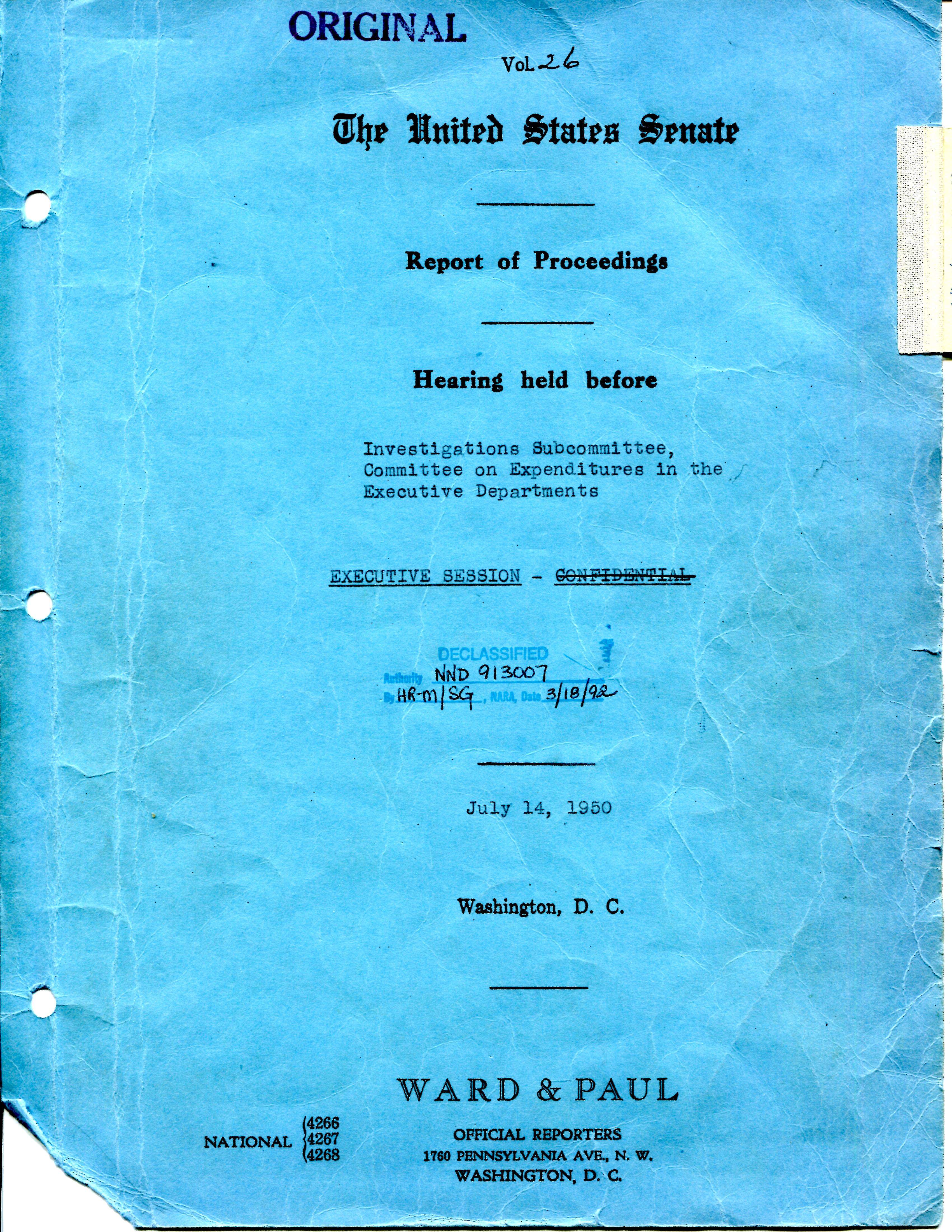

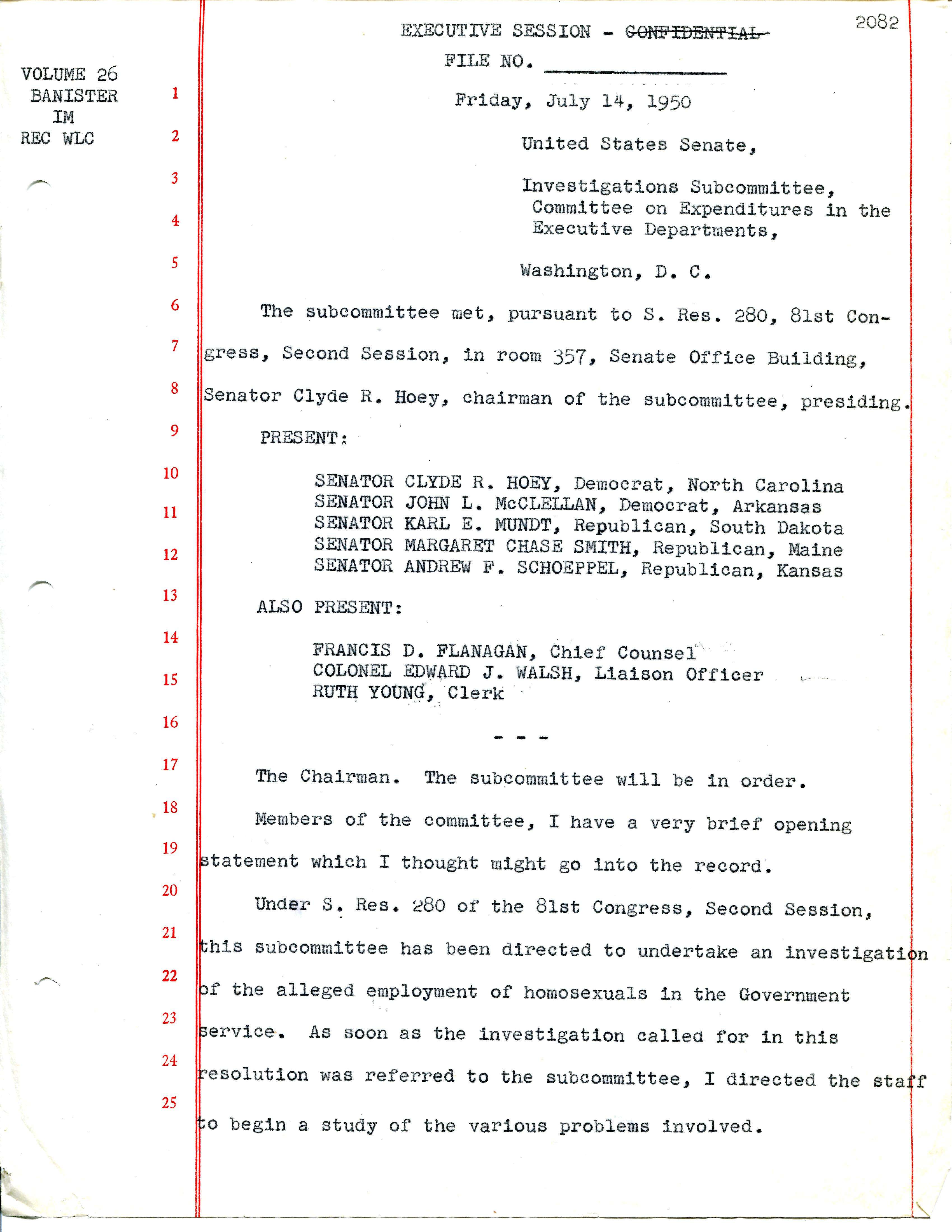

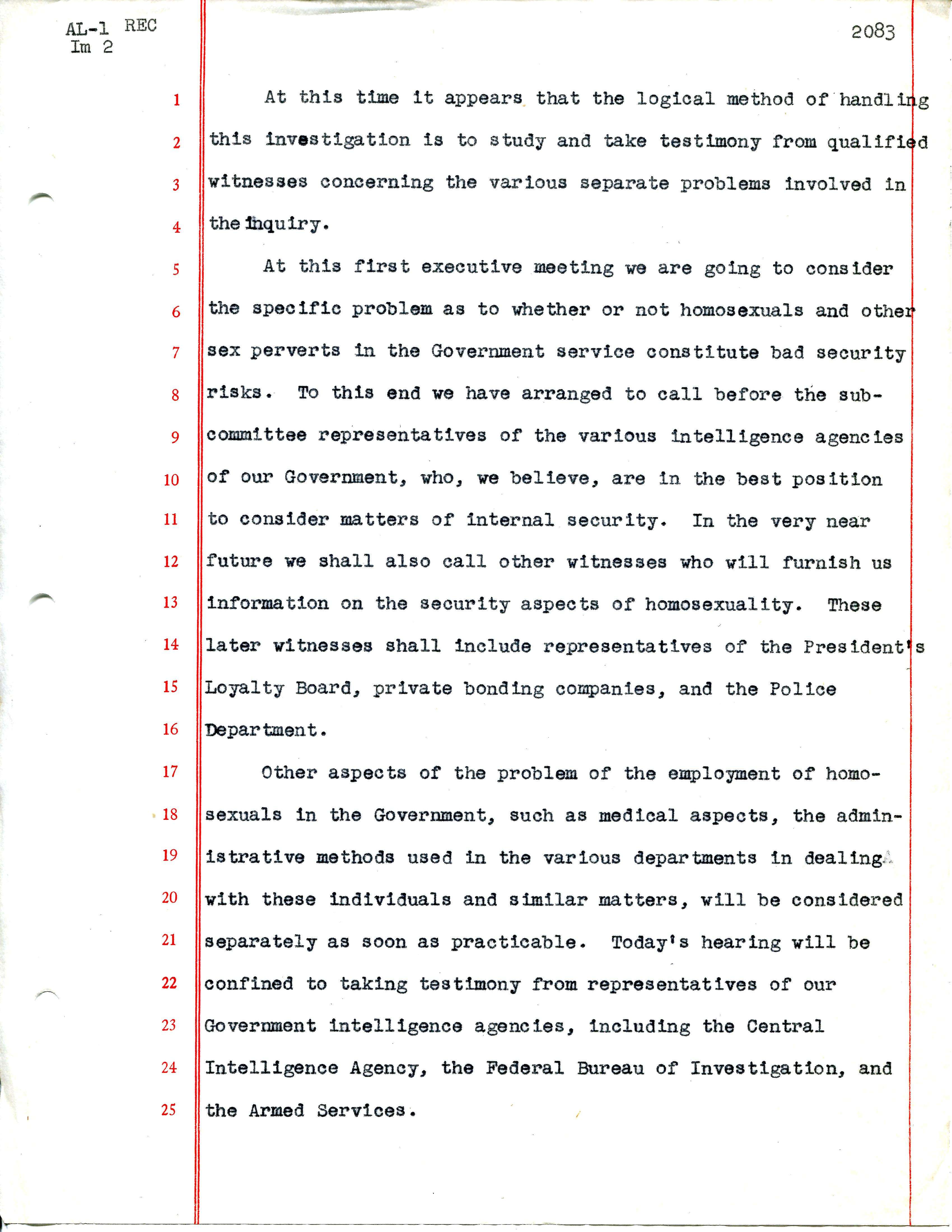

Executive Session Hearing of the Subcommittee on Investigations

Page 1

Activity Element

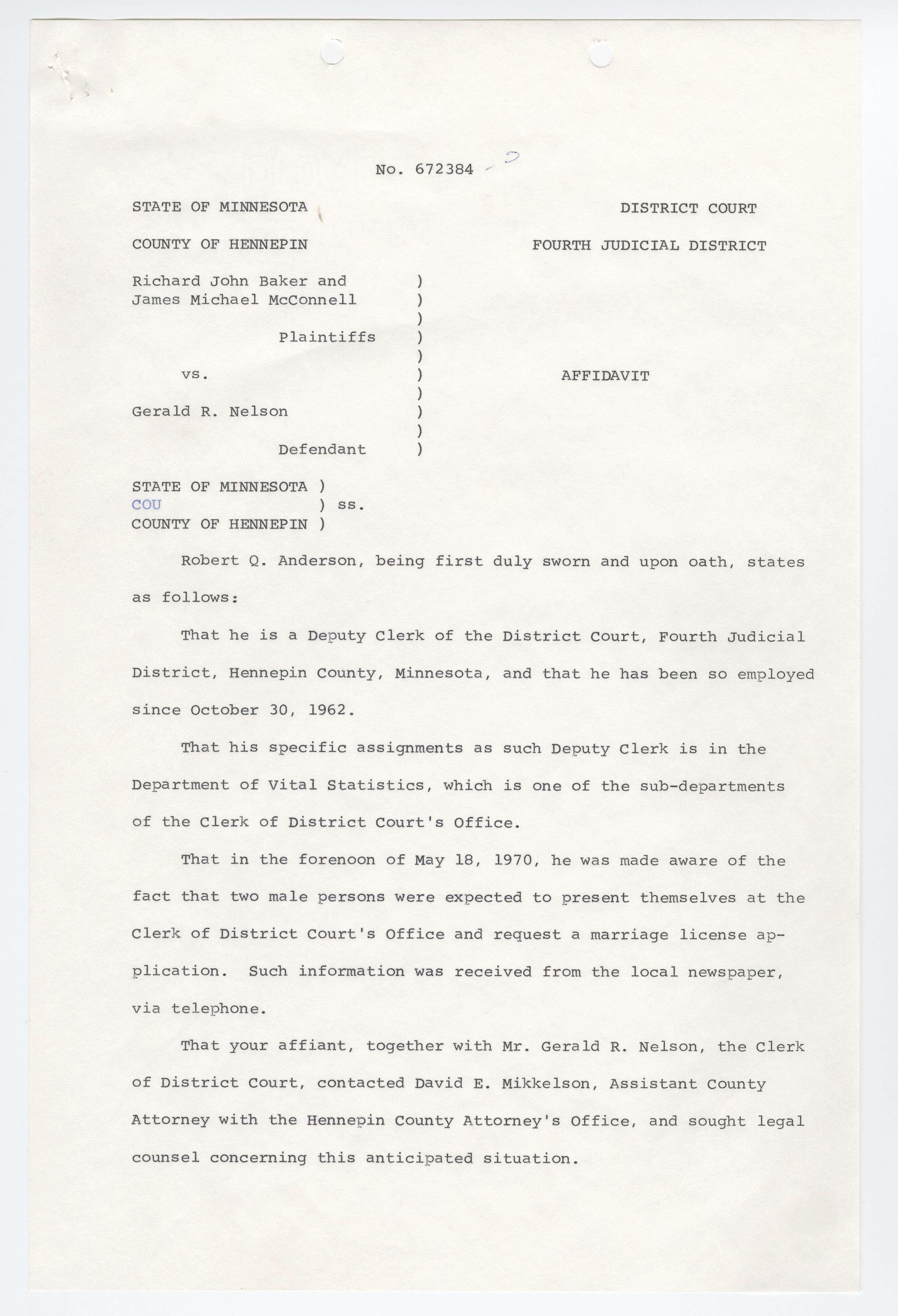

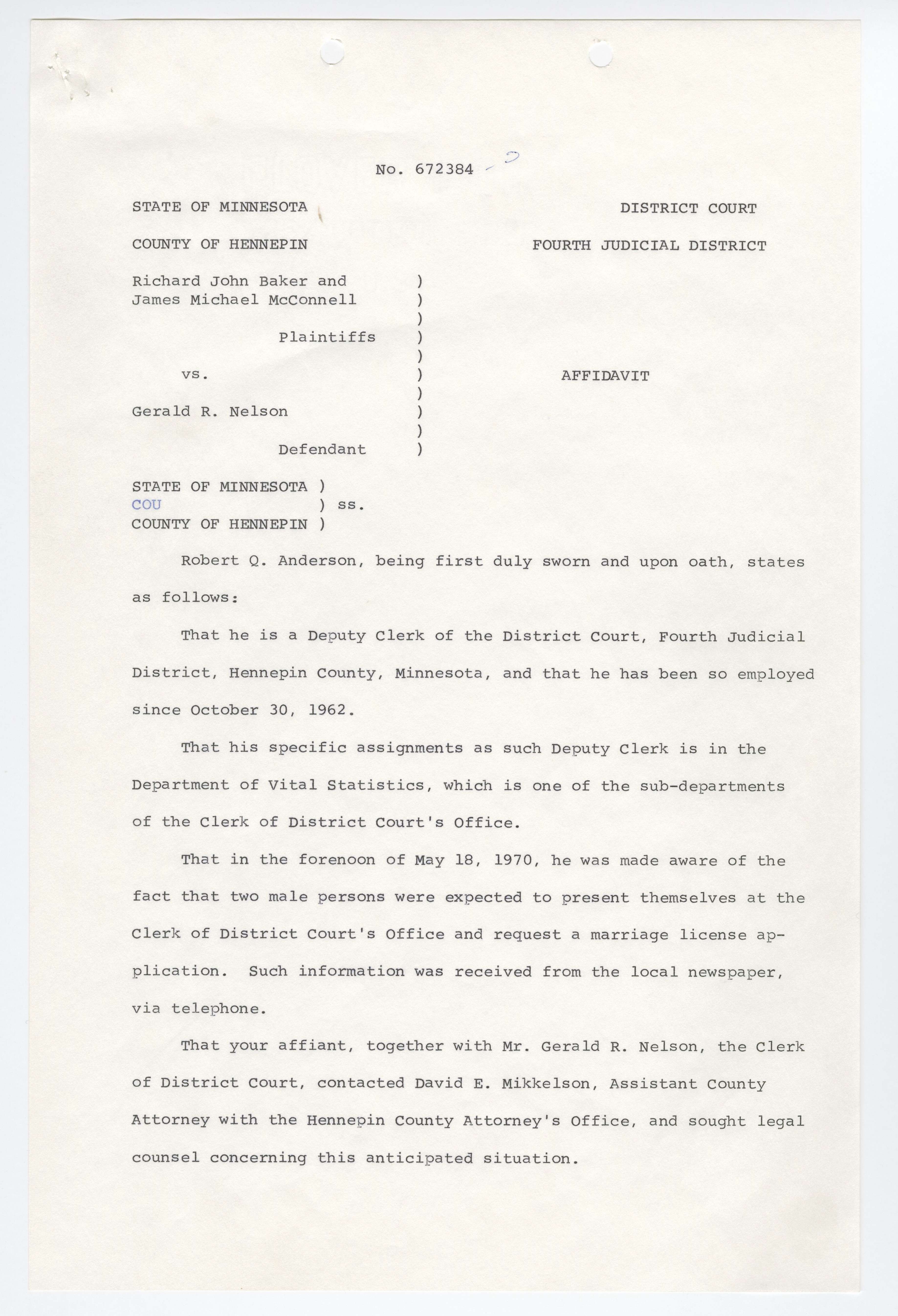

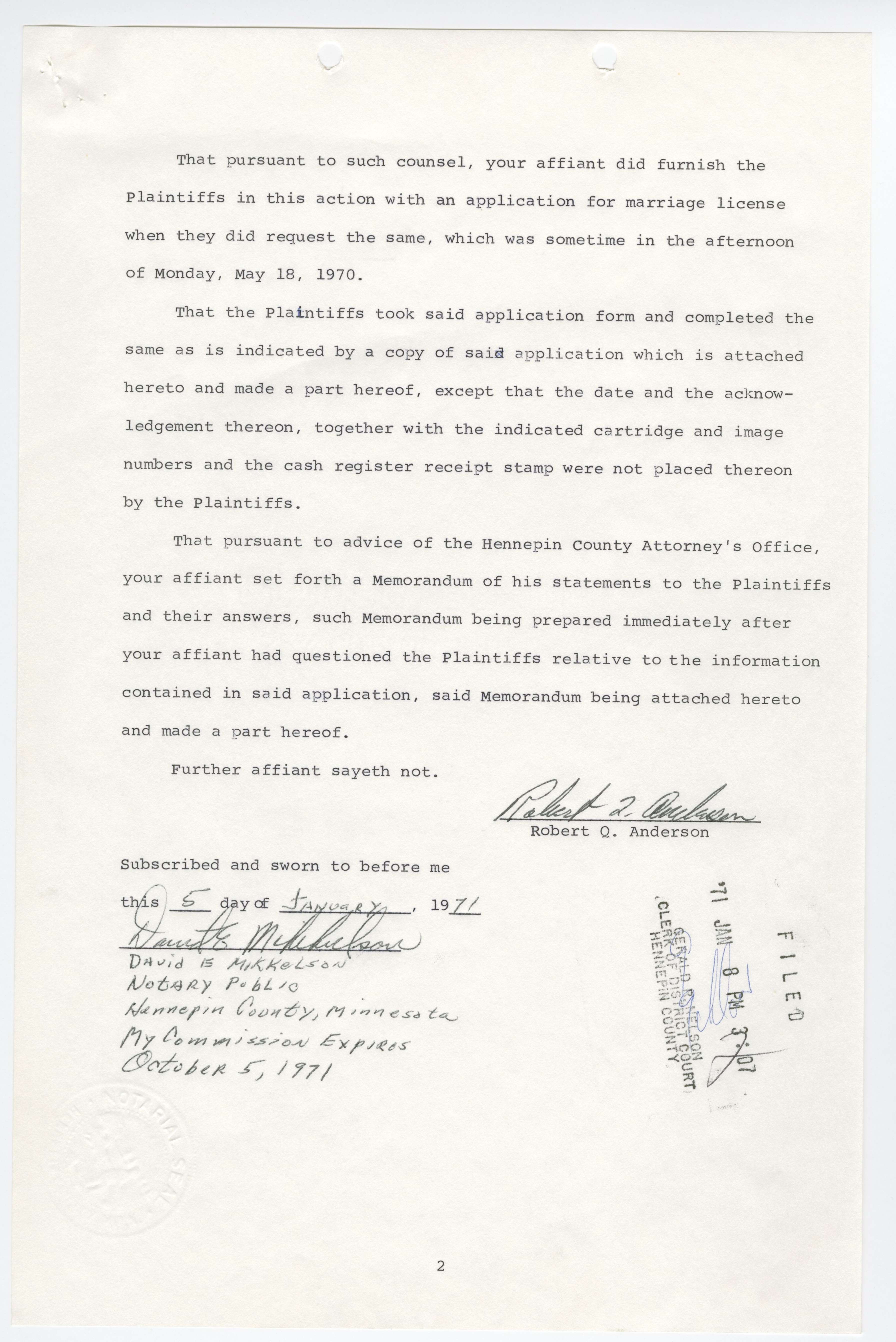

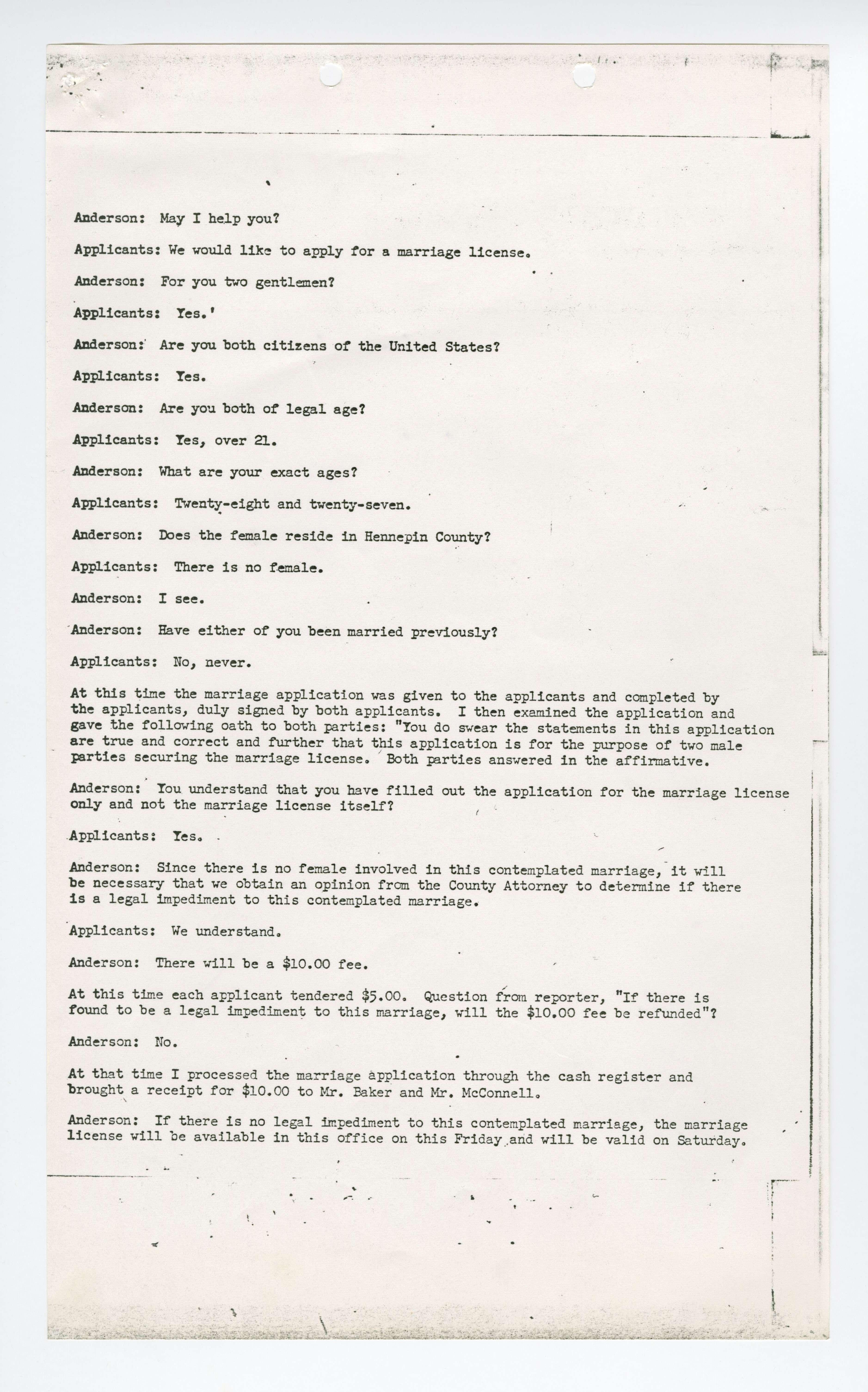

Affidavit of Robert Anderson with Exhibits from Baker v. Nelson

Page 1

Conclusion

The Long Struggle for LGBTQ+ Civil Rights

Finding a Sequence

Answer the following questions in preparation for a class discussion:- Which specific aspects of civil rights do the sources cover?

- What methods did people use to work for change? What arguments did they make to support their point of view?

- What do you think are some of the most important successes of the LGBTQ+ civil rights movement? Why do you think so?

- How do the issues in the historical records relate to civil rights issues today?

Your Response

Document

Executive Session Hearing of the Subcommittee on Investigations

7/14/1950

The largest of these investigations was launched by the Investigations Subcommittee of the Committee on Expenditures in the Executive Departments. Often called the Hoey Committee – after its chairman Clyde Hoey, of North Carolina – it heard testimony from federal officials, the military, and District of Columbia police.

This document contains Senator Hoey's opening statement on the subcommittee's investigation of the employment of homosexuals in the Federal workforce. Additional pages from the July 14th hearing are available in the National Archives online catalog.

Executive Session Hearing of the Subcommittee on Investigations

Page 1

Executive Session Hearing of the Subcommittee on Investigations

Page 2

Executive Session Hearing of the Subcommittee on Investigations

Page 3

Document

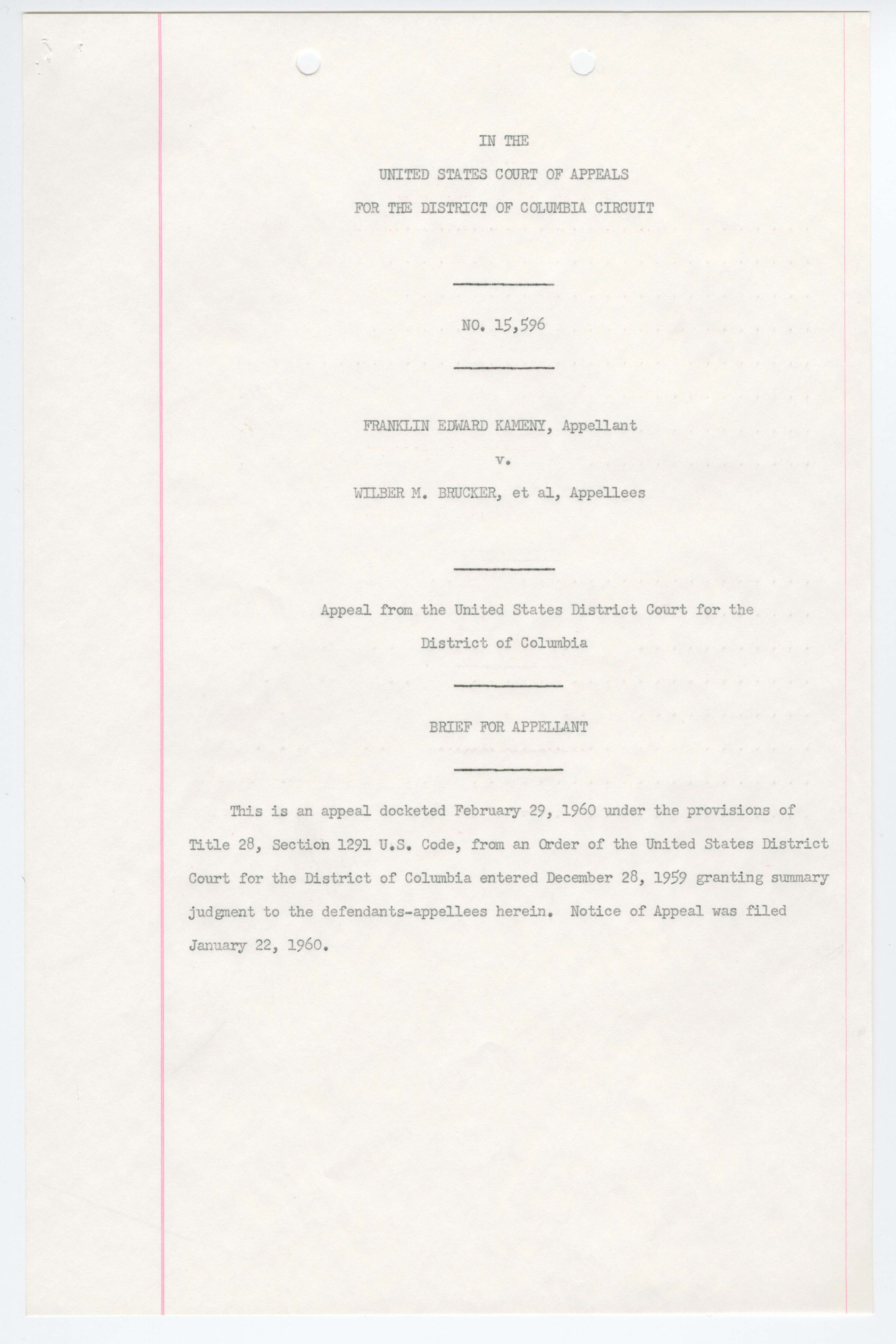

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

1960

Kameny sought to have the termination of his employment overturned by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. That court did not rule in his favor. The documents shown here are his appeal of that lower court decision to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia.

Ulitmately, Kameny appealed his firing all the way to the Supreme Court. When that appeal failed in 1961, Kameny co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., which battled anti-gay discrimination in general and the federal government's exclusionary policies in particular. It was the first gay rights organization in the nation’s capital.

In 1963, Kameny became the first openly gay person to testify before Congress. He did so in defense of Mattachine after Congressman John Dowdy of Texas introduced a bill, H.R. 5990, to try to revoke the organization's permit to operate by amending the existing D.C. Charitable Solicitations Act. Dowdy’s bill stipulated that before granting a fundraising license, the D.C. Board of Commissioners had to certify that the grantee would "benefit or assist in promoting the health, welfare, and the morals of the District of Columbia."

Kameny went on to become a chief organizer of the first gay rights demonstrations in the nation’s capital. In 1965, he led protests at the White House, the Pentagon, and the Civil Service Commission. To remind the country that gay Americans lacked basic civil rights, Kameny and Mattachine joined with other gay rights organizations for "annual reminder" protests at Independence Hall in Philadelphia each Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969. Kameny later ran to become D.C.’s delegate to Congress. He lost the election, but his attempt marked the first time an openly gay candidate had run for Congress.

In 1975, the Civil Service Commission announced new rules stipulating that gay people could no longer be barred or fired from federal employment because of their sexuality.

Select pages of this document are shown. Find the entire court case in the National Archives Catalog.

Transcript

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT__________

NO. 15,596

___________

FRANKLIN EDWARD KAMENY, Appellant

v.

WILBER M. BRUCKER, et al, Appellees

_____________

Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia

________________

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

________________

This is an appeal docketed February 29, 1960 under the provisions of Title 28, Section 1291 U.S. Code, from an Order of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia entered December 28, 1959 granting summary judgment to the defendants appellees herein. Notice of Appeal was filed January 22, 1960.

[pages omitted]

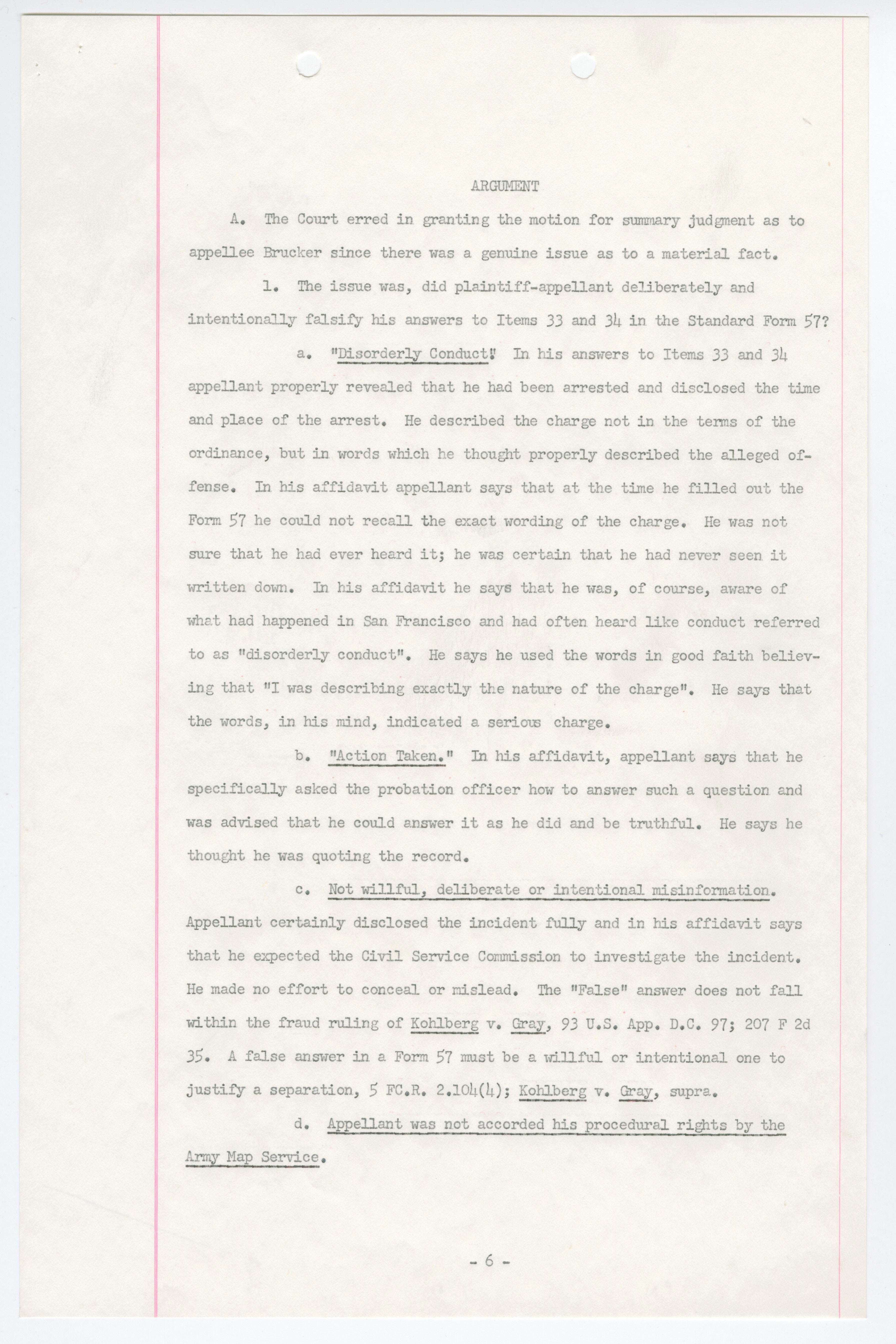

ARGUMENT

A. The Court erred in granting the motion for summary judgment as to appellee Brucker since there was a genuine issue as to a material fact.

1. The issue was, did plaintiff-appellant deliberately and intentionally falsify his answers to Items 33 and 34 in the Standard Form 57?

a. "Disorderly Conduct." [underlined] In his answers to Items 33 and 34 appellant properly revealed that he had been arrested and disclosed the time and place of the arrest. He described the charge not in the terms of the ordinance, but in words which he though properly described the alleged offense. In his affidavit appellant says that at the time he filled out the Form 57 he could not recall the exact working of the charge. He was not sure that he had ever heard it; he was certain that he had never seen it written down. In his affidavit he says that he was, of course, aware of what happened in San Francisco and had often heard like conduct referred to as "disorderly conduct". He says he used the words in good faith believing that "I was describing exactly the nature of the charge". He says that the words, in his mind, indicated a serious charge.

b. "Action Taken." [underlined] In his affidavit, appellant says that he specifically asked the probation officer how to answer such a question and was advised that he could answer it as he did and be truthful. He says he thought he was quoting the record.

c. Not willful, deliberate or intentional misinformation. [sentence underlined] Appellant certainly disclosed the incident fully and in his affidavit says that he expected the Civil Service Commission to investigate the incident. He made no effort to conceal or mislead. The "False" answer does not fall within the fraud ruling of Kolber [underlined] v. Gray [underlined], 93 U.S. App. D.C. 97; 207 F 2d 35. A false answer in a Form 57 must be a willing or intentional one to justify a separation, 5 FC.R. 2.104(4); Kolberg [underlined] v. Gray, [underlined] supra.

d. Appellant was not accorded his procedural rights by the Army Map Service [sentence underlined].

- 6 -

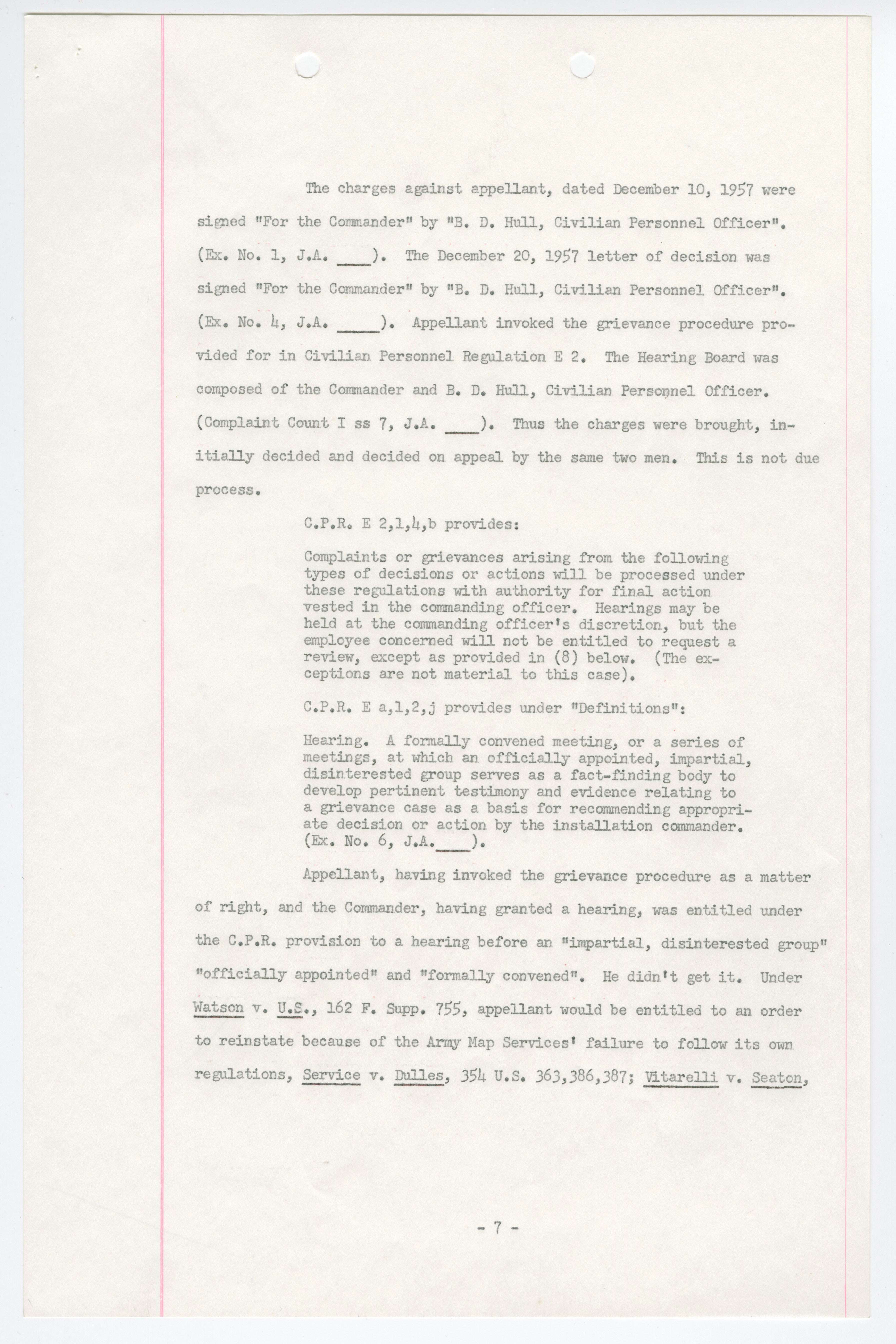

The charges against appellant, dated December 10, 1957 were signed "For the Commander" by "B. D. Hull. Civilian Personal Officer". (Ex. No. 1, J.A. ___)." The December 20, 1957 letter of decision was signed "For the Commander" by "B. D. Hull, Civilian Personal Officer". (Ex. No. 4, J.A. ___)." Appellant invoked the grievance procedure provided for in Civilian Personnel Regulation E 2. The Hearing Board was composed of the Commander and B. D. Hull, Civilian Personnel Officer. (Complaint Count I ss 7, J.A. __). Thus the charges were brought, initially decided and decided on appeal by the same two men. This is not due process.

C.P.R. E 2,1,4,b provides:

Complaints or grievance arising from the following types of decision or actions will be processed under the regulations with authority for final action vested in the commanding Officer. Hearings may be held at the commanding officer discretion, but the employee concerned will not be entitled to request a review, except as provided in (8) below. (The exceptions are not material to this case).

C.P.R. E a, 1, 2, 3, j provides under "Definitions":

Hearing. A formally convened meeting, or a series of meetings, at which an officially appointed, impartial disinterested group serves as a fact-finding body to develop pertinent testimony and evidence relating to a grievance case as a basis for recommending appropriate decision or action by the installation commander. (Ex. No. 6, J.A.__).

Appellant, having invoked the grievance procedure as a matter of right, and the Commander, having granted a hearing, was entitled under the C.P.R. provision to a hearing before an "impartial, disinterested group" "officially appointed" and "formally convened". He didn't get it. Under Watson v. U.S., 162 F. Supp. 755, appellant would be entitled to an order to reinstate because of the Army Map Service' failure to follow its own regulations, Service v. Dulles, 354, U.S. 363,386,387; Vitarelli v. Seaton,

- 7 -

359 U.S. 535,547; Graham v. Richmond, _U.S. App. D.C.__, 272 F. 2d , 522; U.S. ex rel Accardi v. Shaughnessy, 347 U.S. 260.

An order to the Secretary of the Army to reinstate appellant would be ineffective, however, in the face of the Civil Service Commission's finding of unsuitability. The granting of the motion as to appellee Brucker should, however, now be reversed by this Court.

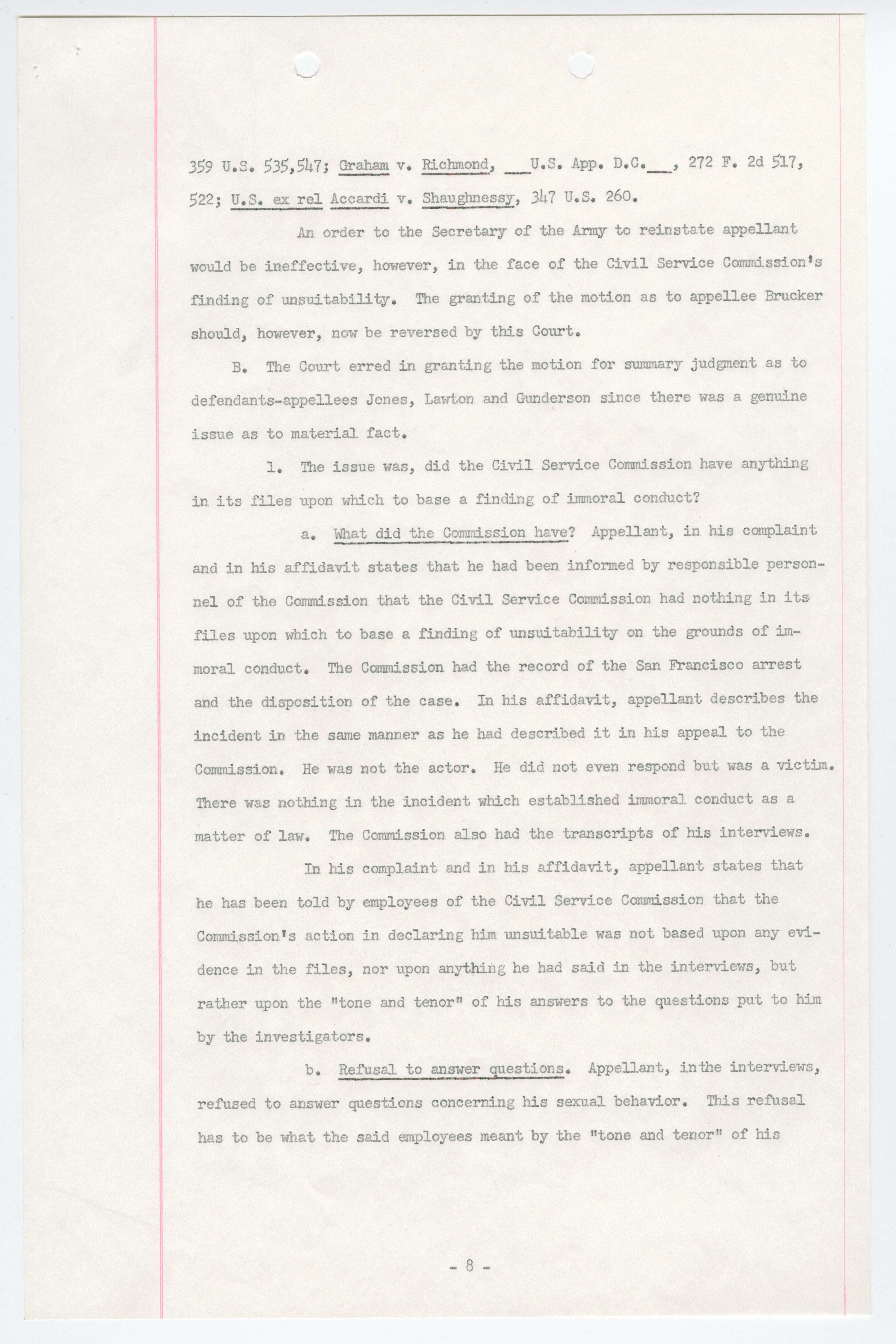

B. The Court erred in granting the motion for summary judgement as to defendant-appellees Jones, Lawton and Gunderson since there was a genuine issue as to material fact.

1. The issue was, did the Civil Service Commission have anything in its files upon which to base a finding of immoral conduct?

a. What did the Commission have? Appellant, in his complaint and in his affidavit states that he had been informed by responsible personnel of the Commission that the Civil Service Commission had nothing in its files upon which to base a finding of unsuitability on the grounds of immoral conduct. The Commission had the record of the San Francisco arrest and the disposition of the case. In his affidavit, appellant describes the incident in the same manner as he had described it in his appeal to the Commission. He was not the actor. He did not even respond but was a victim. There was nothing in the incident which established immoral conduct as a matter of law. The Commission also had the transcripts of his interviews.

In his complaint and in his affidavit, appellant states that he has been told by employees of the Civil Service Commission that the Commission's section in declaring his unsuitable was not based upon any evidence in the files, nor upon anything he had said in the interviews, but rather upon the "tone and tenor" of his answers to the questions put to him by the investigators.

b. Refusal to answer questions. Appellant, in the interviews, refused to answer questions concerning his sexual behavior. This refusal has to be what the said employee meant by the "tone and tenor" of his

- 8 -

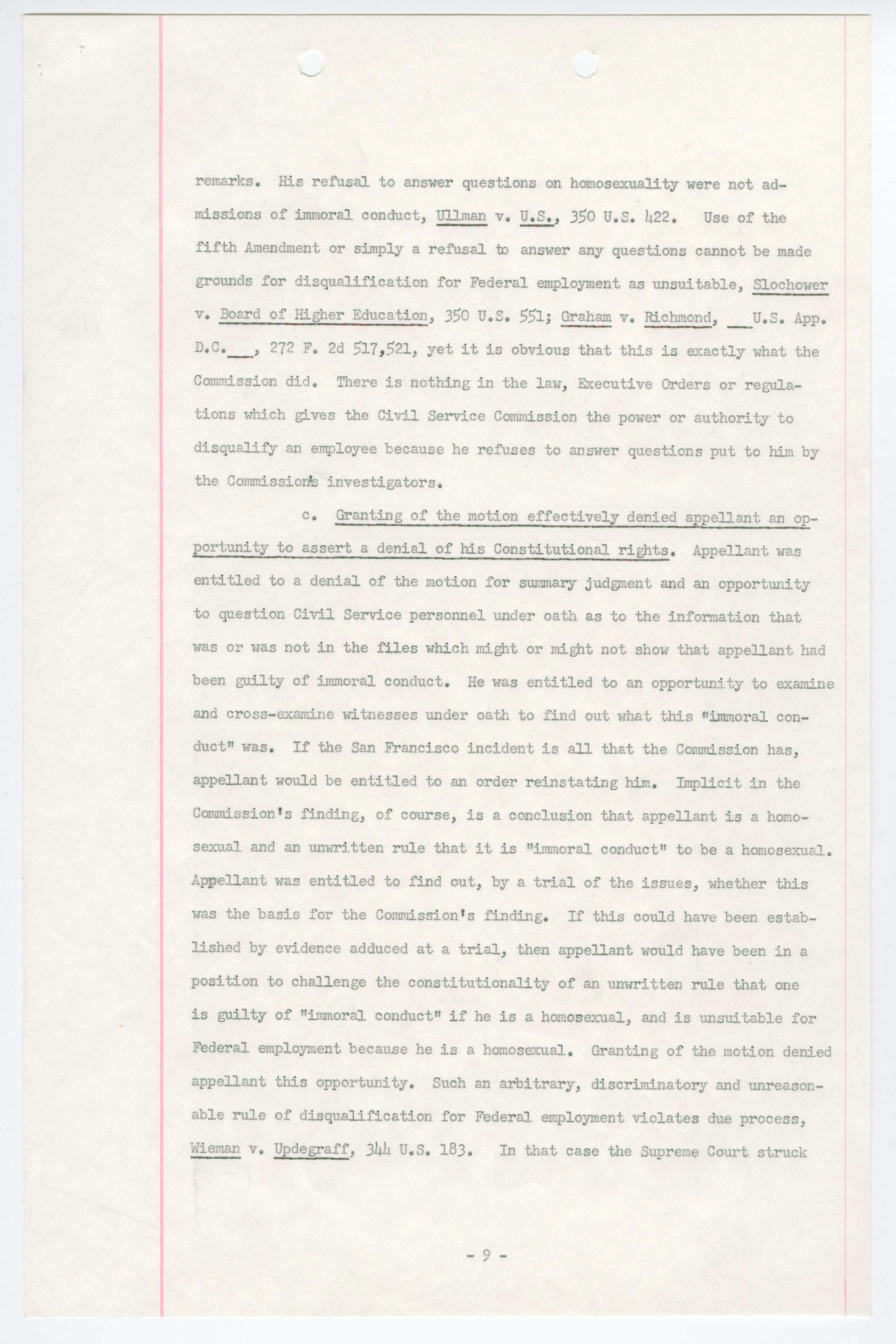

remarks. His refusal to answer questions on homosexuality were not admissions of immoral conduct, UIIman v. U.S., 350 U.S. 422. Use of the fifth Amendment or simply a refusal to answer any questions cannot be made grounds for disqualification for Federal employment as unsuitable, SIochower v. Board Of Higher Education, 350 U.S. 551; Graham v. Richmond, __U.S. App. D.C.__, 272 F. 2d 517,521, yet it is obvious that this is exactly what the Commission did. There is nothing in the law, Executive Orders or regulations which gives the Civil Service Commission the power or authority to disqualify an employee because he refuses to answer questions put to him by the Commissions Investigators.

c. Granting of the motion effectively denied appellant an opportunity to assert a denial of his Constitutional rights. Appellant was entitled to a denial of the motion for summary judgement and an opportunity to question Civil Service personnel under oath as to the information that was not in the files which might or might not show that appellant had been guilty of immoral conduct. He was entitled to an opportunity to examine and cross-examine witnesses under oath to find out what this "immoral conduct" was. If the San Francisco incident is all that the Commission has appellant would be entitled to an order reinstating him. Implicit in the Commission's finding, of course, is a conclusion that appellant is a homosexual and an unwritten rule that it is "immoral conduct" to be a homosexual. Appellant was entitled to find out, by a trial of the issues, whether this was the basis for the Commission's finding. If this could have been established by evidence adduced at a trial, then appellant would have been in a position to challenge the constitutionally of an unwritten rule that one is guilty of "immoral conduct" if he is a homosexual, and is unsuitable for Federal employment because he is a homosexual. Granting of the motion denied appellant this opportunity. Such an arbitrary, discriminatory and unreasonable rule of disqualification of Federal employment violates due process, Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183. In that case the Supreme Court struck

- 9 -

down a so-called 'loyalty oath' because it based employability solely on the fact of membership in certain organizations. The Court pointed out that membership itself may be innocent and held that the classification of innocent and guilty together was arbitrary. In SIochower, supra, the Court said that the Wieman case "rests squarely on the proposition that 'constitutional protection does extend to the public servant whose exclusion pursuant protection does extend to the public servant whose exclusion pursuant to a statute is patently arbitrary or discriminatory'". Proof, or even a tacit admission, that a person is a homosexual does not, standing alone, prove that he has been guilty of immoral conduct. Disqualification of homosexuals for employment by the Government is arbitrary, discriminatory, and unreasonable, and denies to each member of the group (sizable, it is said) equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution.

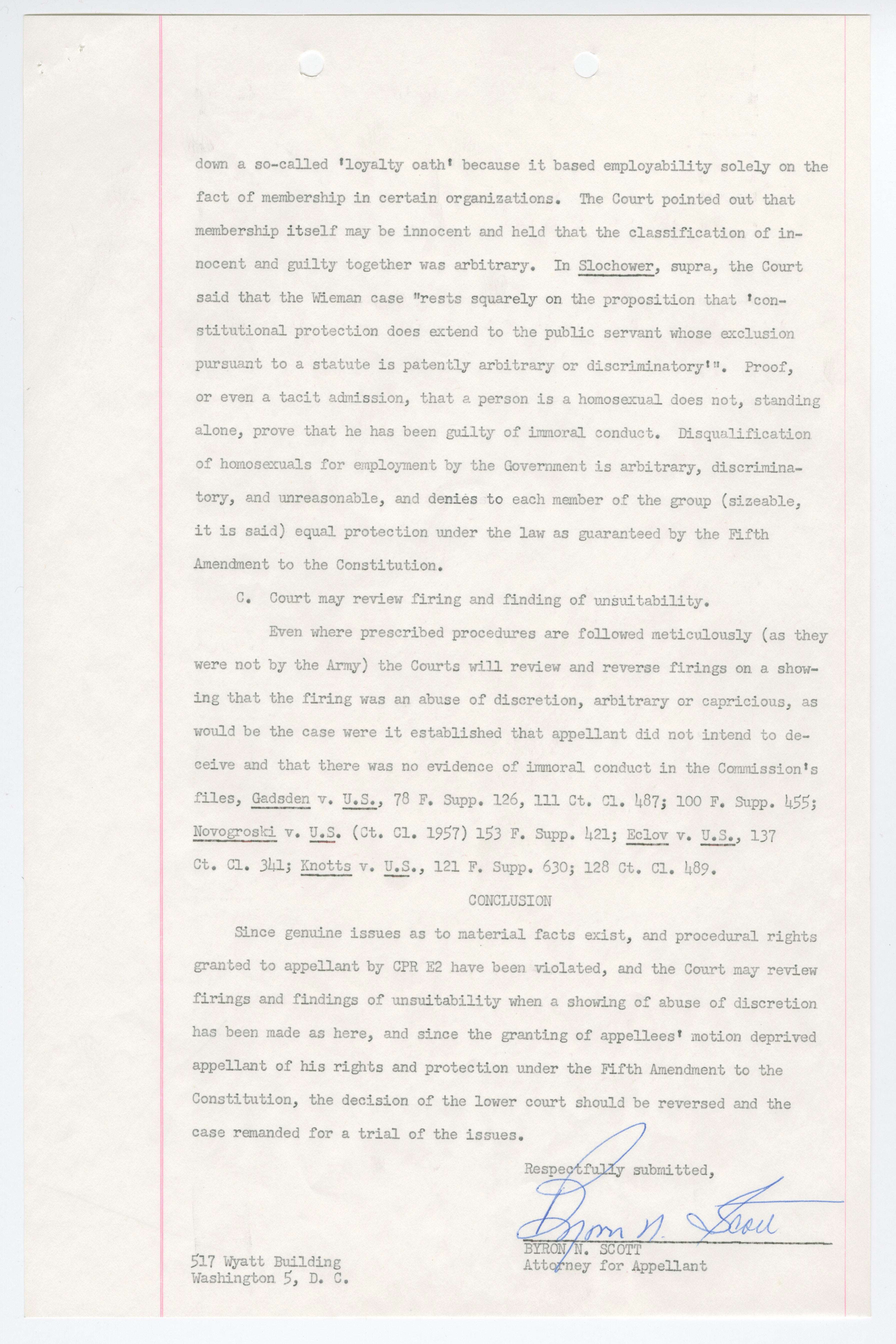

C. Court may review firing and finding of unsuitability. Even where prescribed procedures are followed meticulously (as they were not by the Army) the Courts will review and reverse firings on a showing that the firing was an abusive of discretion, or capricious, as would be the case were it established that appellant did not intend to deceive and that there was no evidence of immoral conduct in the Commission's files, Gadaden v. U.S., 78 F. Supp. 126, 111, Ct. CI. 487; 100 F. Supp. 455; Novogroski v. U.S. (Ct. CI. 1957) 153 F. Supp. 421; Eclov v. U.S. 137 Ct. CI. 341; v. U.S., Knotts v. U.S., 121 F. Supp. 630; 128 Ct. CI. 489.

Conclusion

Since genuine issues as to material facts exist, and procedural rights granted to appellant by CPR E2 have been violated, and the Court may review firings and findings of unsuitability when a showing of abuse of discretion has been made as here, and since the granting of appellees' motion deprived appellant of his rights and protection under the Fifth Amendment to the Constitution, the decision of the lower court should be reversed and the case remanded for a trial of the issues.

Respectfully submitted,

[signature]

BYRON N. SCOTT

Attorney for Appellant

517 Wyatt Building

Washington 5, D. C.

[pages omitted]

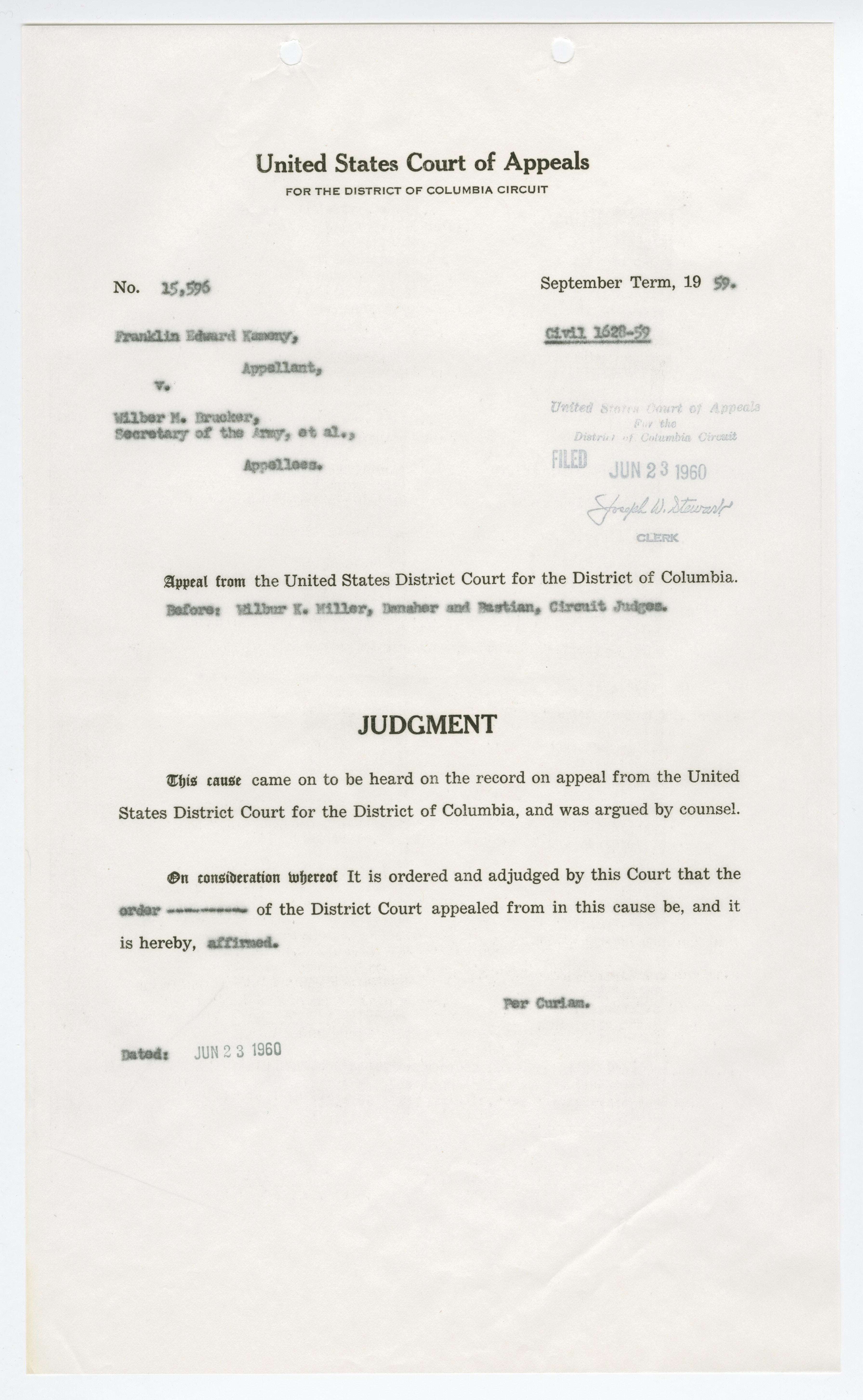

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 15,596 September Term, 1959.

Franklin Edward Kameny, Appellant,

v.

Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellees.

Civil 1628-59

[stamp] United States Court of Appeals For the District of Columbia Circuit FILED JUN 23 1960 Joseph W. Stewart CLERK

Appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia.

Before: Wilbur K. Miller, Danaher and Bastian, Circuit Judges.

JUDGMENT

This cause came on to be heard on the record on appeal from the United States District Court for the District of Columbia, and was argued by counsel.

On consideration whereof It is ordered and adjudged by this Court that the order of the District Court appealed from in this cause be, and it is hereby, affirmed.

Per Curiam.

Dated: JUN 23 1960

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 1

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 2

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 3

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 4

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 5

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 6

Franklin Edward Kameny v. Honorable Wilber M. Brucker, Secretary of the Army, et al., Appellee

Page 7

Document

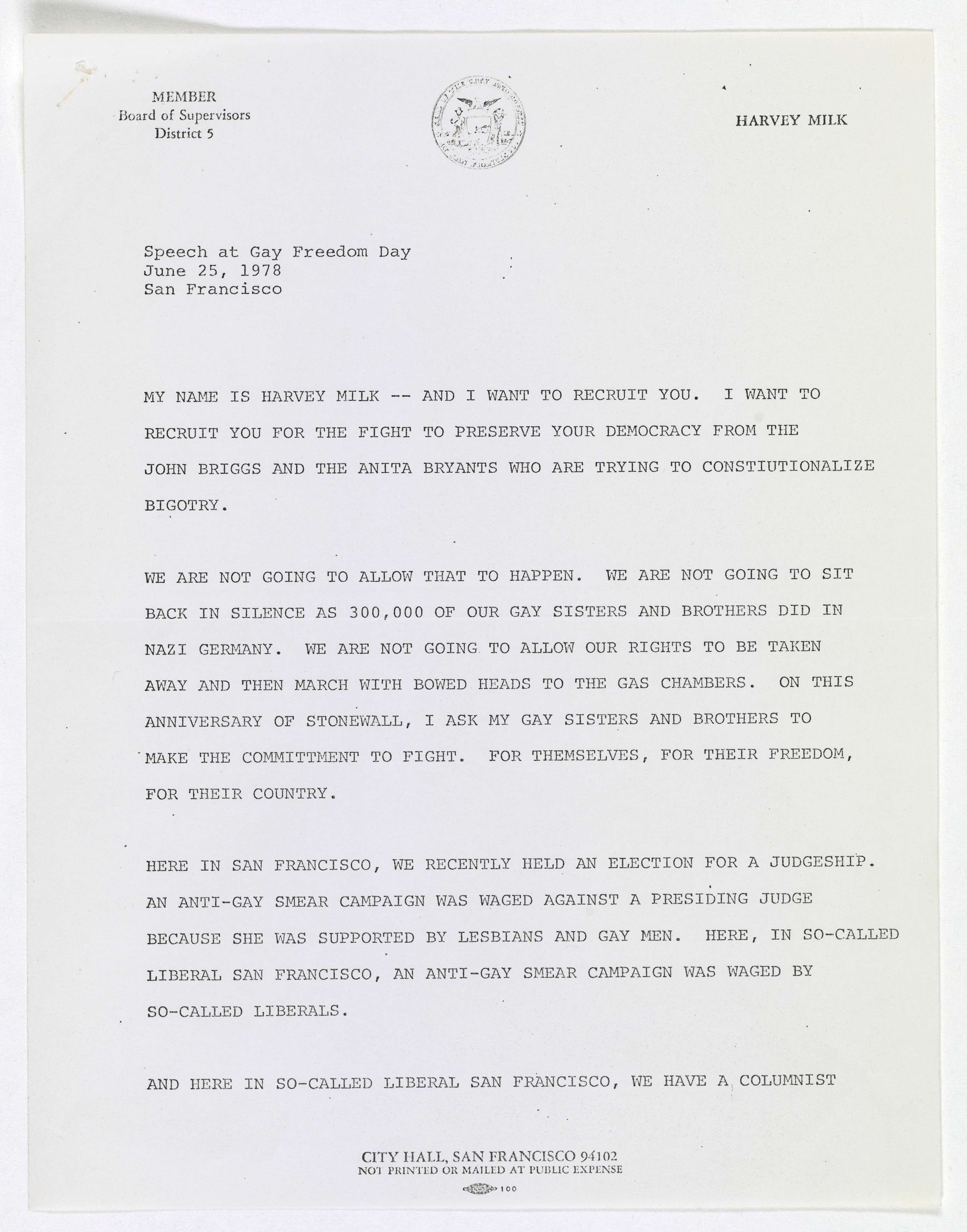

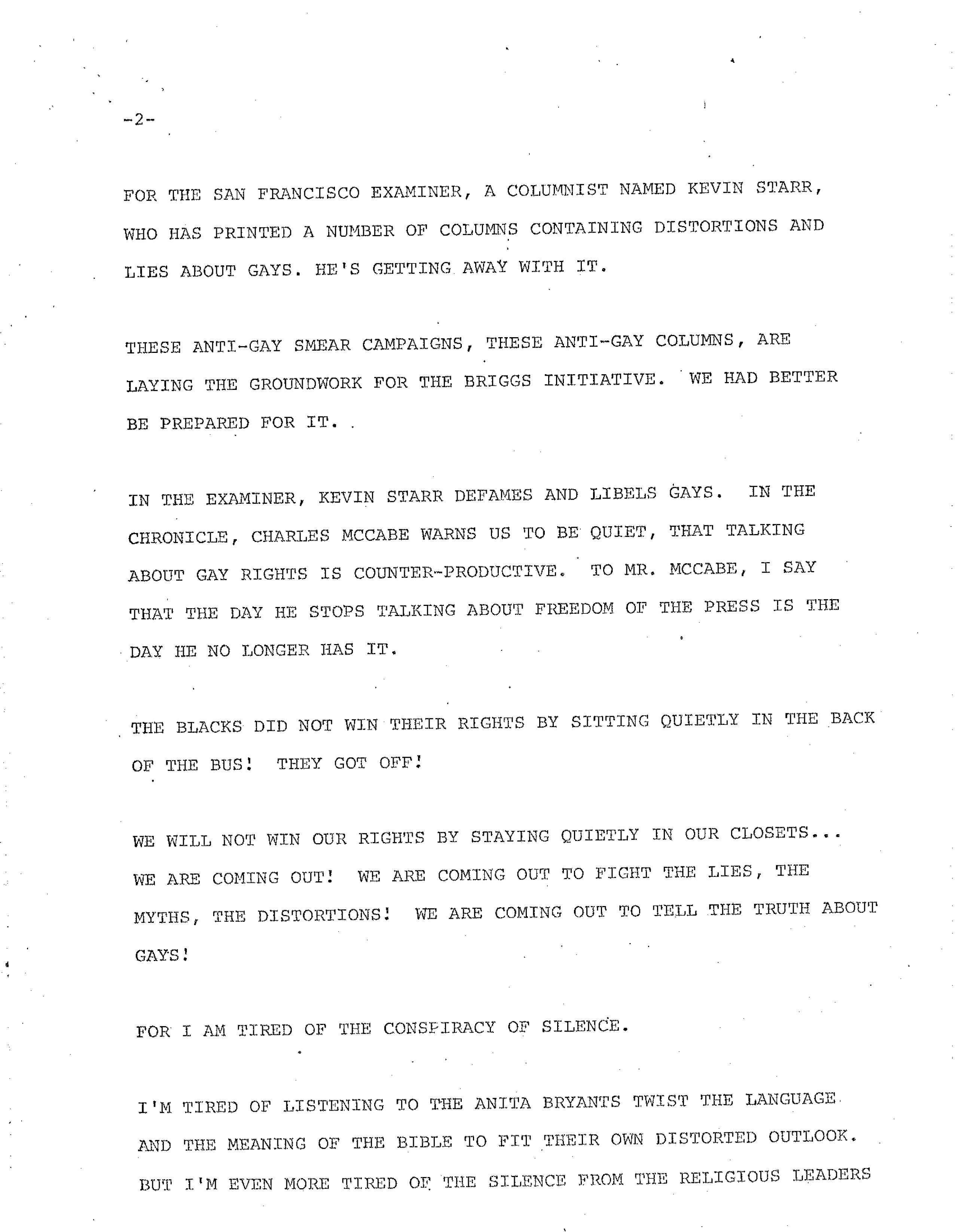

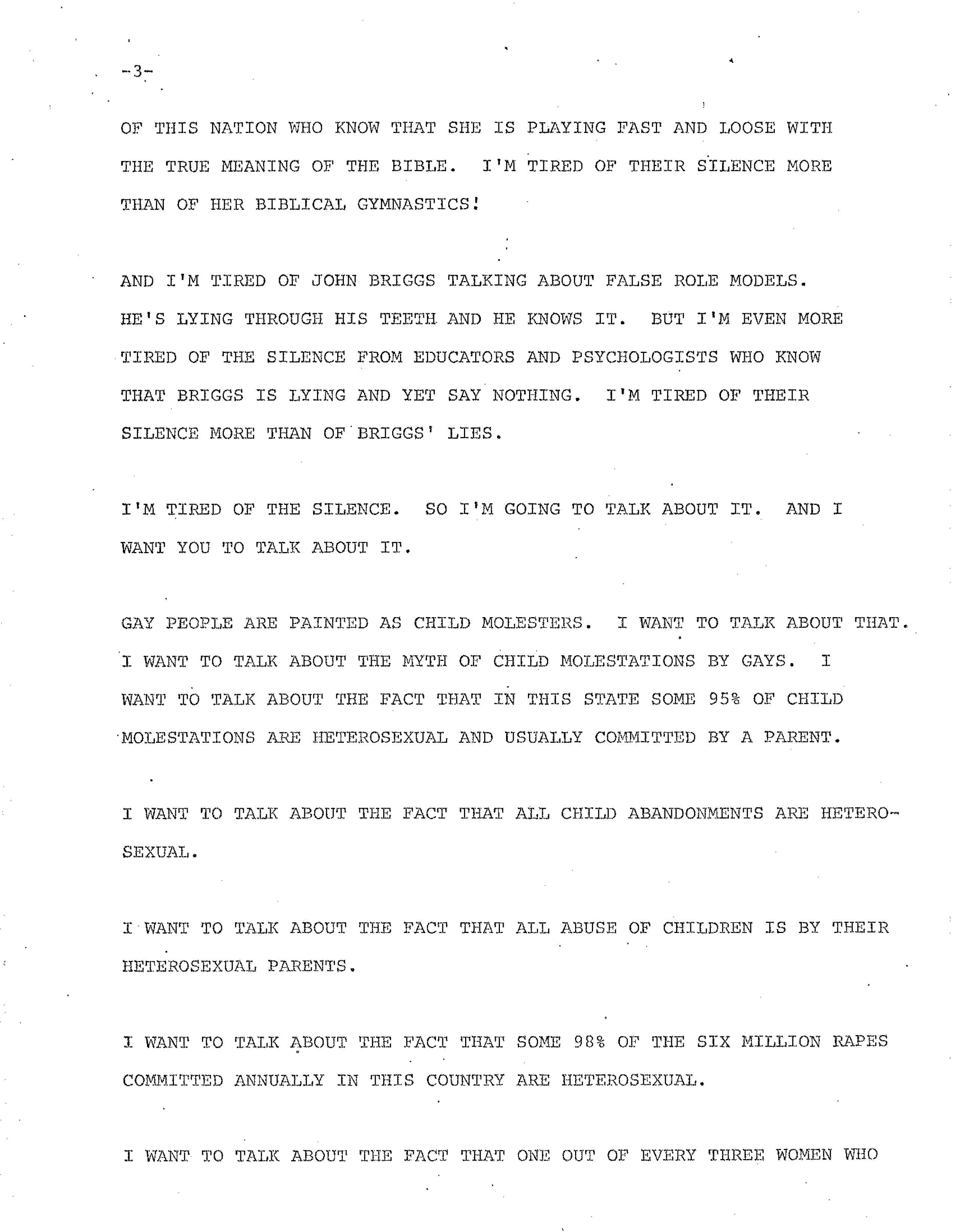

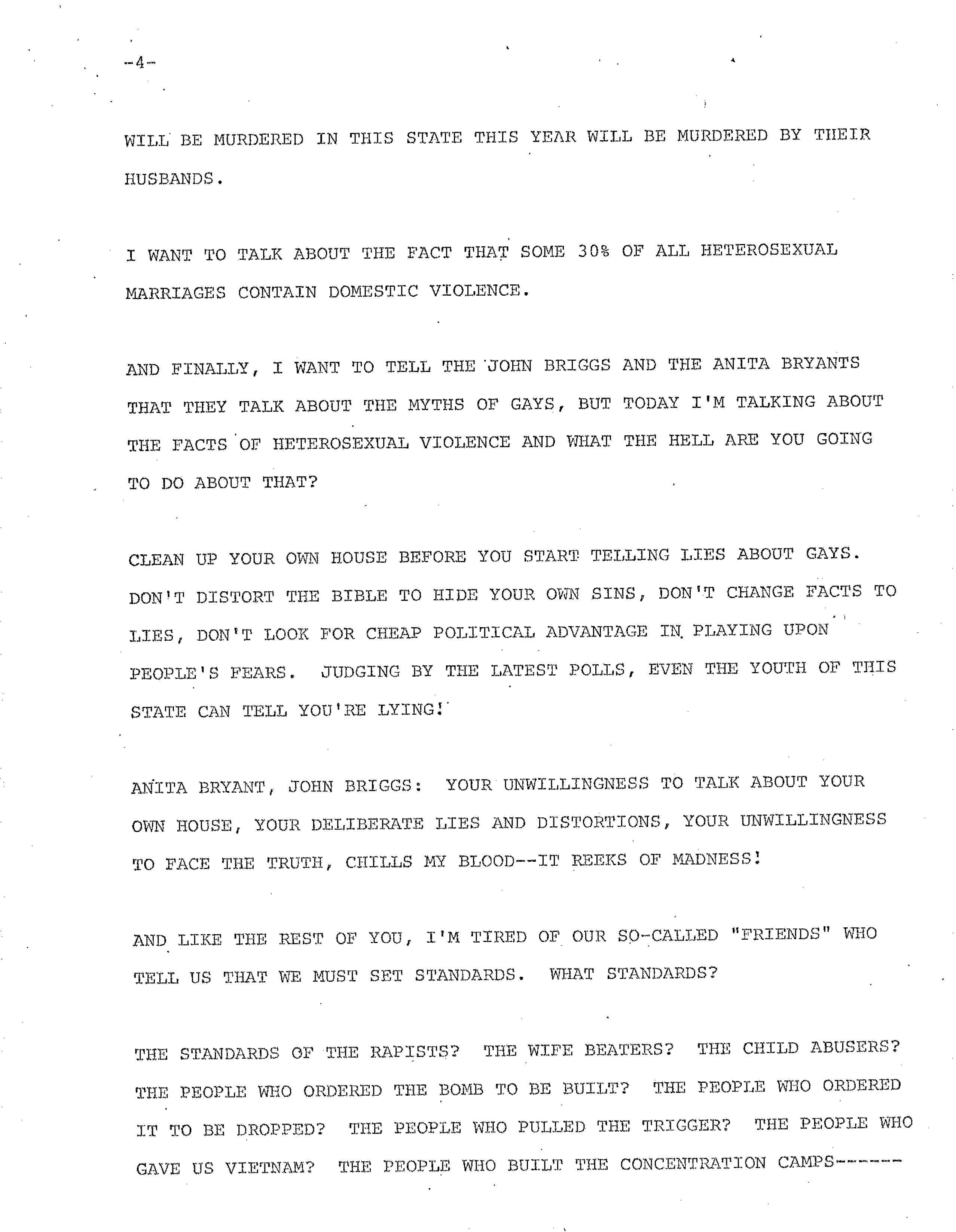

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

6/25/1978

Milk was speaking out against Proposition 6, also known as the Briggs Initiative—named after state legislator John Briggs, who sponsored the legislation. Proposition 6 would have banned gay and lesbian individuals from working in California public schools, and made their firing mandatory. Milk campaigned against Proposition 6 throughout California, attending every event Briggs hosted to protest the proposition.

Harvey Milk was the first openly gay person to be elected to public office in California when he was elected to the San Francisco Board of Supervisors. He used his platform as supervisor to promote LGBTQ rights, and other public initiatives such as free public transportation, increased access to affordable child care, and a police oversight committee.

In the Hope Speech, Milk called for his "gay sisters and brothers to make the commitment to fight" against Proposition 6 and other similarly discriminatory legislation in an effort to promote gay rights in California and across the United States. And he challenged Briggs and others to reexamine American history:

On the Statue of Liberty it says, "Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to be free...." In the Declaration of Independence it is written "All men are created equal and they are endowed with certain inalienable rights...." That’s what America is. No matter how hard you try, you cannot erase those words from the Declaration of Independence. No matter how hard you try, you cannot chip those words from off the base of the Statue of Liberty.Milk also expressed his frustration at the "silence from the White House....There are some 15 to 20 million lesbians and gay men in this country listening and listening very carefully. Jimmy Carter, when are you going to talk about their rights?"

In case the President had not read the speech, Milk sent him this copy along with a letter. He hoped that the President would oppose the Briggs Initiative and "take a leadership role in defending the rights of gay people."

President Carter did eventually state his opposition to the Briggs Initiative, citing its potential infringement on individual rights. On November 7, 1978, the proposition was defeated by more than 1 million votes.

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 1

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 2

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 3

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 4

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 5

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 6

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 7

Harvey Milk's Speech at San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Celebration

Page 8

Document

Harvey Milk's Application for Appointment to Commissioned Rank of Ensign

11/14/1951

This is his application for appointment to the rank of Ensign, showing the recommendation to approve his commission and describing him as "an industrious young man...cooperative, diligent and has a deep sense of responsibility...considered very good officer material."

Milk would next be promoted to Lieutenant (junior grade), but his military career was soon to come to a close. In December 1954, Milk was questioned by Special Agents of the Office of Naval Intelligence for "suspected homosexual conduct."

In a signed statement, Milk acknowledged that he had been sexually intimate with a number of men. He submitted his resignation from the Navy under "other than honorable conditions" recognizing that he could "expect to encounter substantial prejudice in civilian life...."

Harvey Milk's Application for Appointment to Commissioned Rank of Ensign

Page 1

Harvey Milk's Application for Appointment to Commissioned Rank of Ensign

Page 2

Harvey Milk's Application for Appointment to Commissioned Rank of Ensign

Page 3

Harvey Milk's Application for Appointment to Commissioned Rank of Ensign

Page 4

Document

'Hi, is this Jim?'

6/26/2015

In Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court ruled that the right to marry is a fundamental liberty and is protected under the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the 14th Amendment. The decision required states to both issue marriage licenses between same-sex couples and recognize marriages between same-sex couples performed in any state.

The decision came exactly two years after the decision in United States v. Windsor required the Federal Government to treat same-sex marriages equally under the law.

Obergefell v. Hodges originated as the lower court case case of Obergefell v. Kasich in 2013. James Obergefell and his husband, John Arthur, sued Ohio Governor John Kasich for discrimination against same-sex couples who married lawfully out of state and, later, to force the state of Ohio to recognize same-sex unions on death certificates.

Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court case, is the amalgamation of four court cases from Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee—Obergefell v. Hodges (2014), Tanco v. Haslam (2013), Bourke v. Beshear (2013), and DeBoer v. Snyder (2012)—all challenging the constitutionality of those states' bans on same-sex marriage.

In response to the Supreme Court's decision, Obergefell said, "No other person will learn at the most painful moment of married life, the death of a spouse, that their lawful marriage will be disregarded by the state. No married couple who moves will suddenly become two single persons because their new state ignores their lawful marriage."

Transcript

Male Speaker: I have to interrupt, I'm sorry.Pamela Brown is on the steps and she's with

Mr. Obergerfell who is getting a phone call from a

very important person.

Pamela?

Pamela Brown: Yes, and that very important person, Jake,

is President Obama calling Jim Obergerfell.

Jim Obergerfell: Hello?

The President: Hi, is this Jim?

Jim Obergerfell: Yes, it is, Mr. President.

The President: Jim, the -- I, I figured when I saw you

that we were going to be hoping for some good news

and we did it.

And I just wanted to say congratulations.

Jim Obergerfell: Thank you so much, Sir.

I think was your wishes.

The President: You know, your leadership on this, you

know, has changed -- changed the country.

Jim Obergerfell: I really appreciate that,

Mr. President.

It's really been an honor for me to be involved in

this fight and to have been able to, you know, fight for

my marriage and live up to my commitments to my

husband.

So, I appreciate -- I appreciate everything you've

done for the LGBT community and it's really an honor to

have become part of that fight.

The President: Well, I'm really proud of you and, you

know, just -- just know that, you know, not only

have you been a great example for people but

you're also going to, you know, bring about a lasting

change in this country.

And it's pretty rare where that happens.

So, I couldn't be prouder of you and your husband and

God bless you.

Jim Obergerfell: Thank you sir, that means an

incredible amount to me, and, yeah -- thank you.

The President: All right, take care.

Jim Obergerfell: Thanks for the call, Mr. President.

The President: You bet, bye bye.

Jim Obergerfell: Bye.

Pamela Brown: Jim, when you hear the President say to

you that your leadership has changed the country what is --

'Hi, is this Jim?'

Page 1

Document

President Barack Obama Greets Frank Kameny in the Oval Office

6/17/2009

In 1957, Franklin Kameny had been fired from his job in the Army Map Service as an astronomer because of his sexual orientation. This happened during a time known as the Lavender Scare. Beginning in the late 1940s and continuing through the 1960s, thousands of gay employees were fired or forced to resign from the federal workforce because of their sexuality. This wave of repression was also bound up with anti-Communism and fueled by the power of congressional investigation.

Kameny appealed his firing all the way to the Supreme Court. When that appeal failed in 1961, Kameny co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., which battled anti-gay discrimination in general and the federal government's exclusionary policies in particular. It was the first gay rights organization in the nation’s capital.

In 1963, Kameny became the first openly gay person to testify before Congress. He did so in defense of Mattachine after Congressman John Dowdy of Texas introduced a bill, H.R. 5990, to try to revoke the organization's permit to operate by amending the existing D.C. Charitable Solicitations Act. Dowdy’s bill stipulated that before granting a fundraising license, the D.C. Board of Commissioners had to certify that the grantee would "benefit or assist in promoting the health, welfare, and the morals of the District of Columbia."

Kameny went on to become a chief organizer of the first gay rights demonstrations in the nation’s capital. In 1965, he led protests at the White House, the Pentagon, and the Civil Service Commission. To remind the country that gay Americans lacked basic civil rights, Kameny and Mattachine joined with other gay rights organizations for "annual reminder" protests at Independence Hall in Philadelphia each Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969. Kameny later ran to become D.C.’s delegate to Congress. He lost the election, but his attempt marked the first time an openly gay candidate had run for Congress.

In 1975, the Civil Service Commission announced new rules stipulating that gay people could no longer be barred or fired from federal employment because of their sexuality. In 2009, President Barack Obama issued "Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies on Federal Benefits and Non-Discrimination" in order "to achieve greater equality for the Federal workforce through extension to same-sex domestic partners of benefits currently available to married people of the opposite sex."

President Barack Obama Greets Frank Kameny in the Oval Office

Page 1

Document

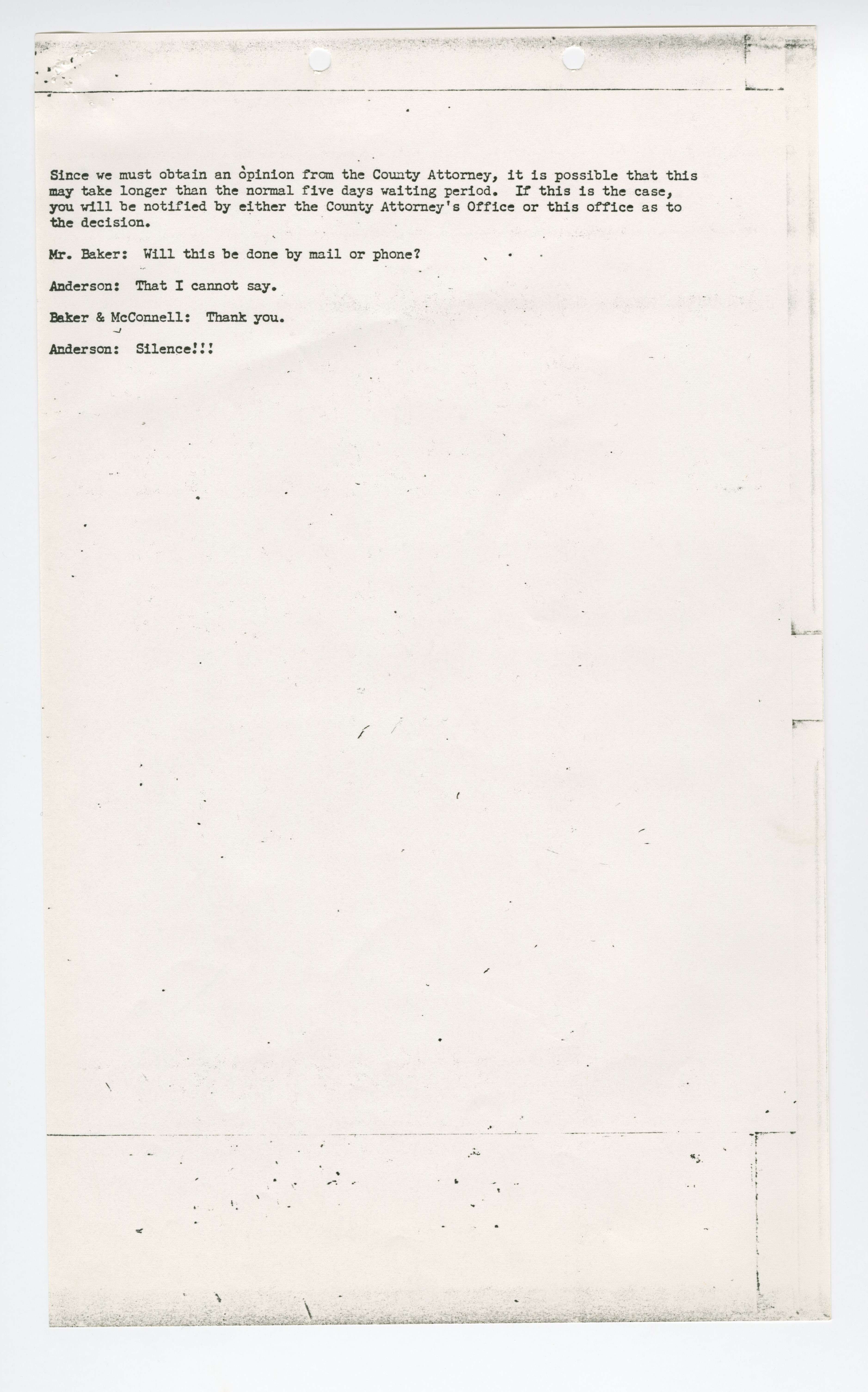

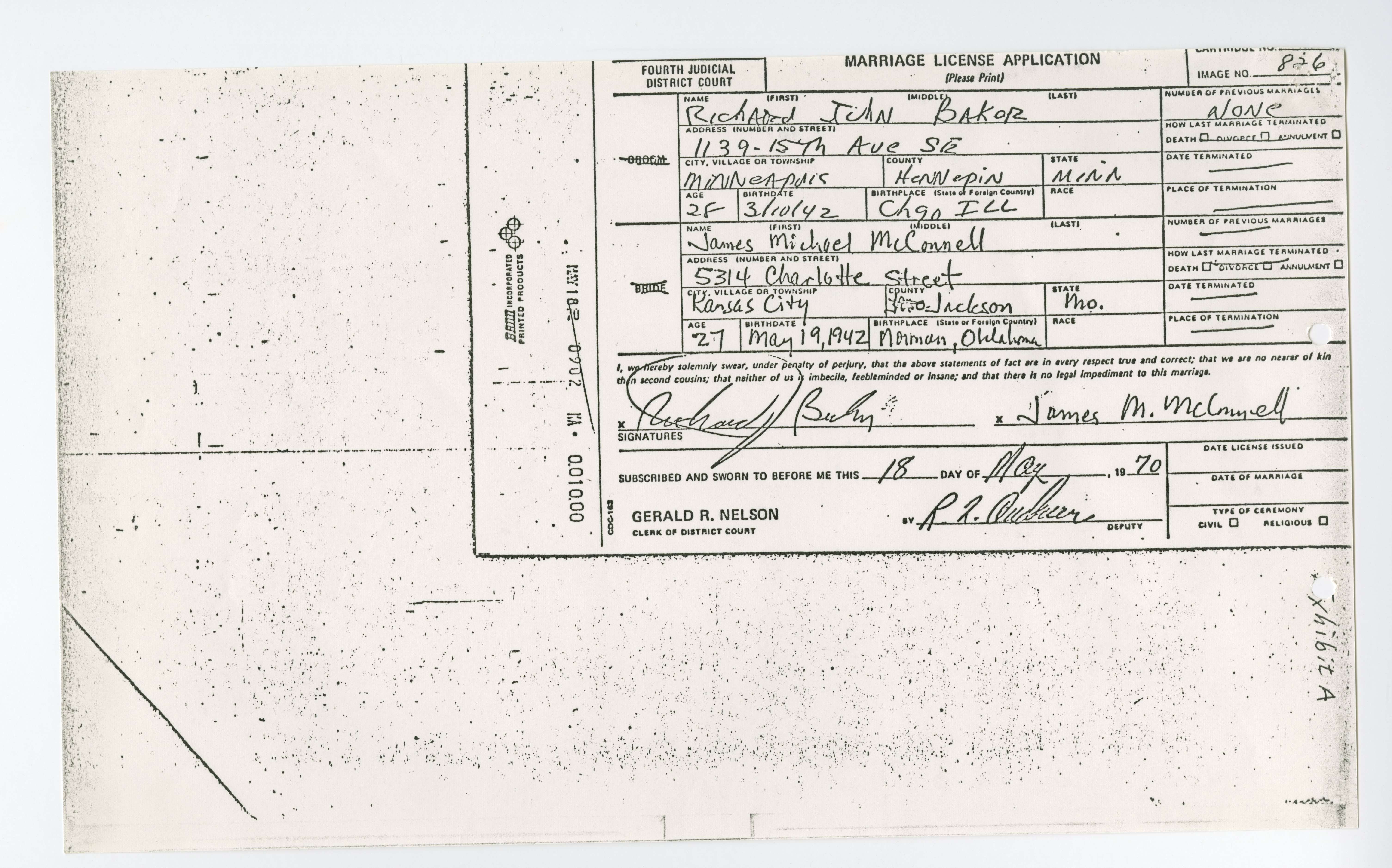

Affidavit of Robert Anderson with Exhibits from Baker v. Nelson

1/8/1971

The deputy clerk of the court, Robert Anderson, accepted their application, but would not issue a license unless the County Attorney approved; the application was later denied.

Baker and McConnell took their case to a Minnesota District Court, which dismissed the couple's claims, and then to the state Supreme Court, which affirmed the lower court's ruling. As part of these proceedings, Robert Anderson, the Deputy Clerk of the District Court, composed this recollection (affidavit) of his interaction with Baker and McConnell.

On October 10, 1972, Baker and McConnell appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. It denied their claim, stating "The appeal is dismissed for want of a substantial federal question," meaning the Court decided the issue did not directly relate to Federal laws.

Affidavit of Robert Anderson with Exhibits from Baker v. Nelson

Page 1

Affidavit of Robert Anderson with Exhibits from Baker v. Nelson

Page 2

Affidavit of Robert Anderson with Exhibits from Baker v. Nelson

Page 3

Affidavit of Robert Anderson with Exhibits from Baker v. Nelson

Page 4

Affidavit of Robert Anderson with Exhibits from Baker v. Nelson

Page 5

Document

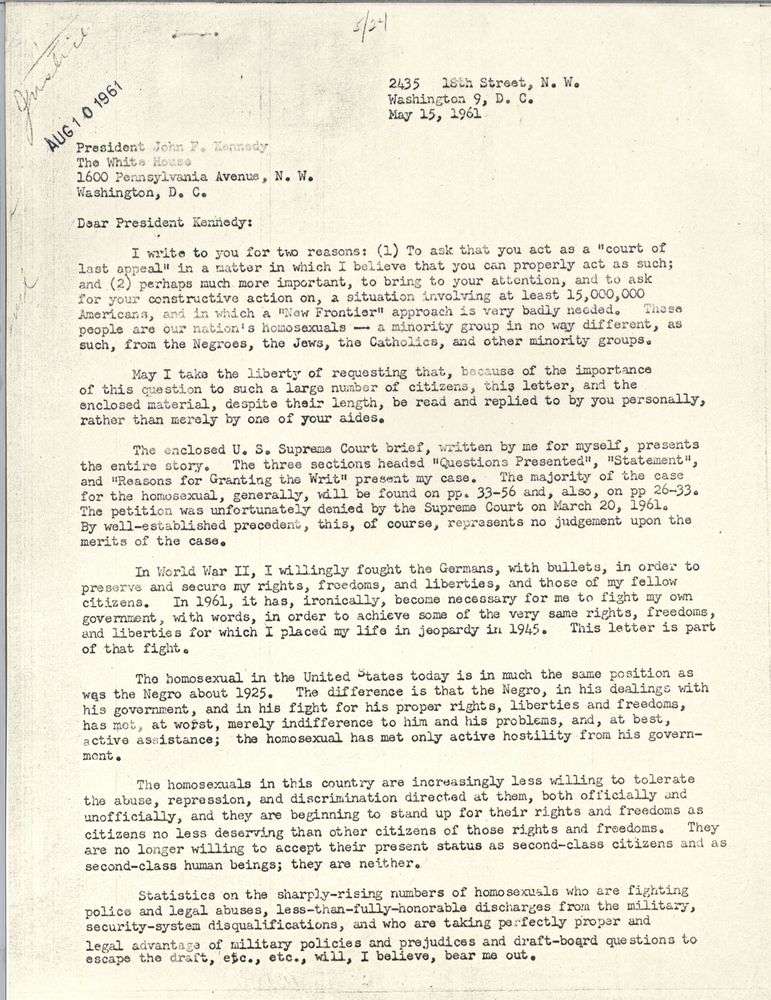

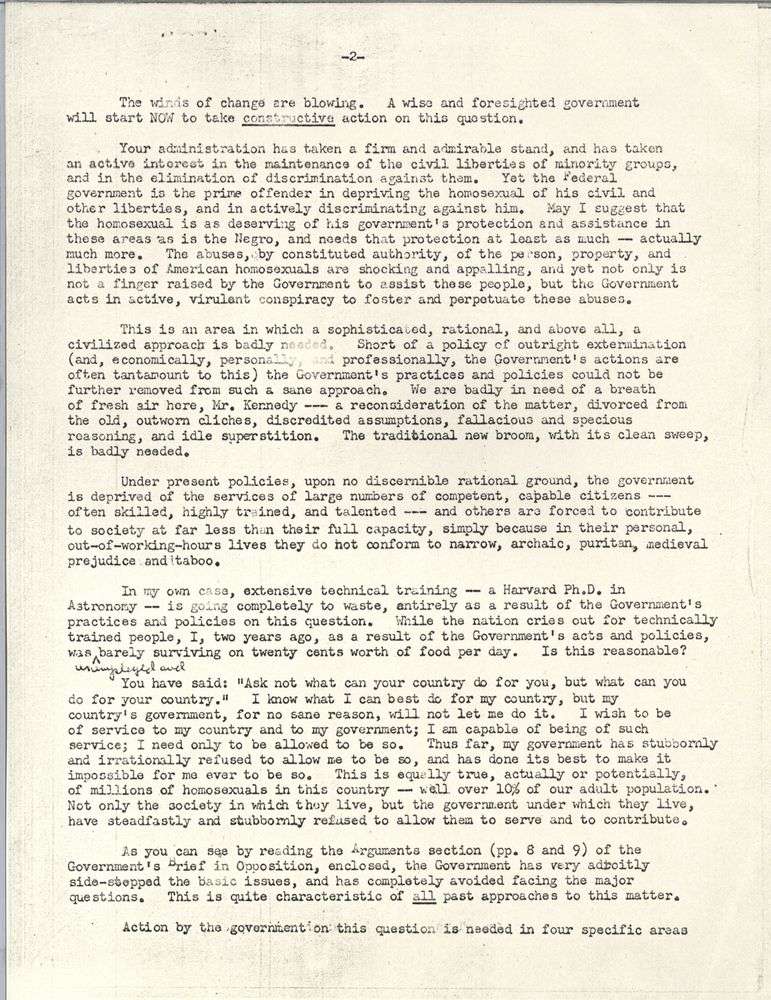

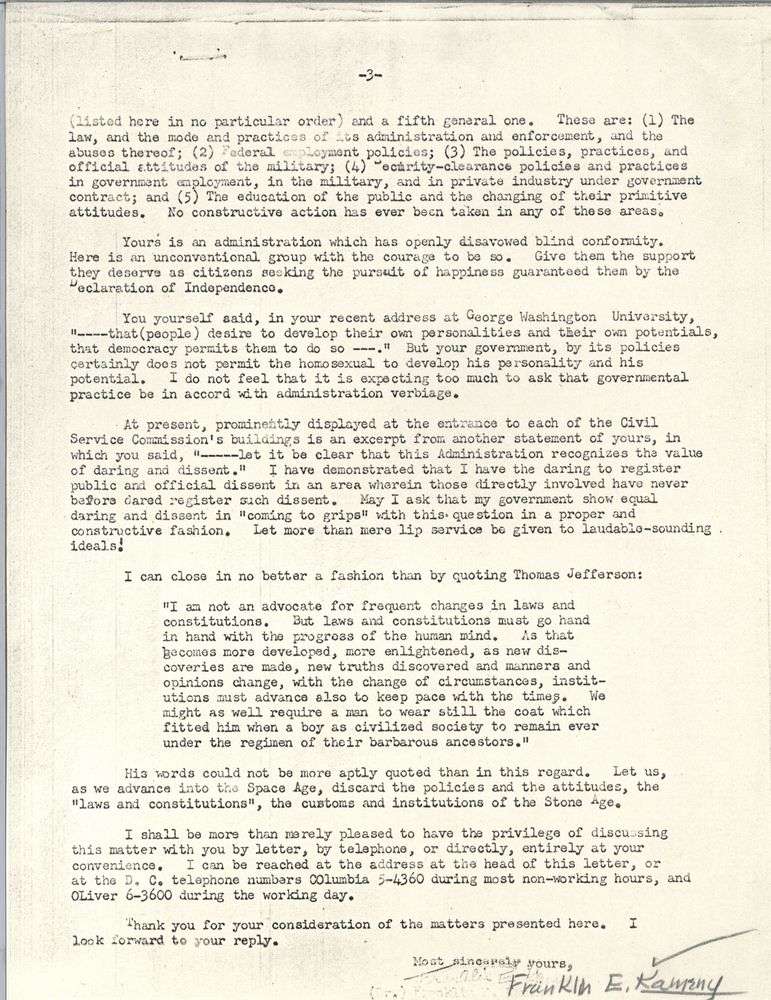

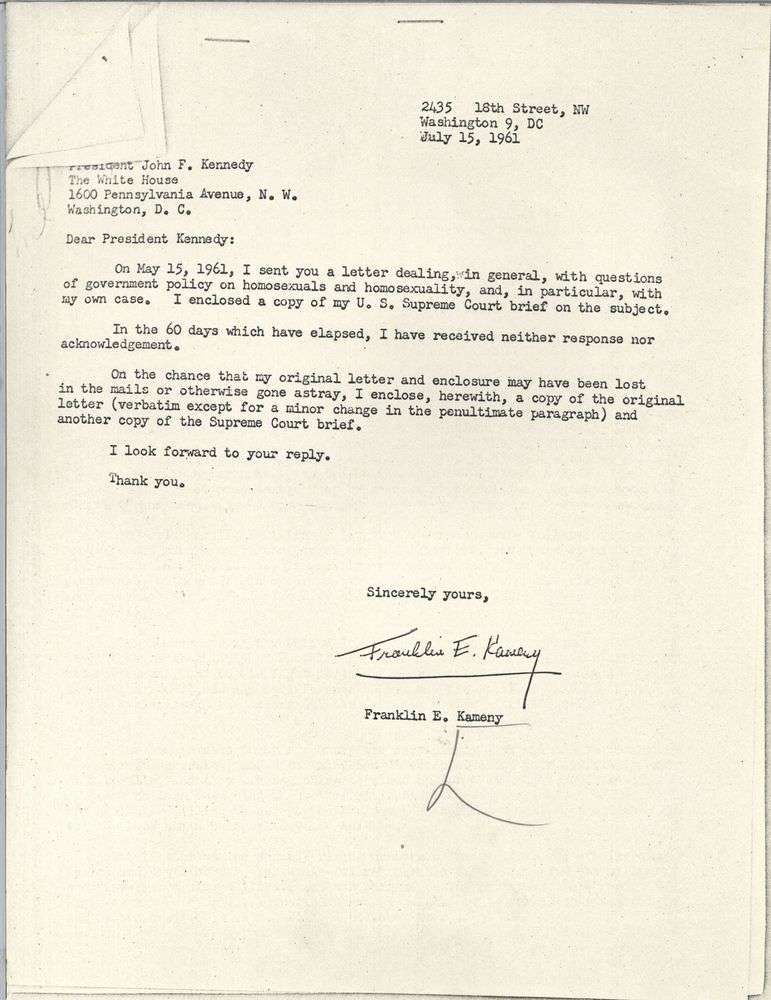

Letter from Franklin E. Kameny to President John F. Kennedy

5/15/1961

In 1957, Kameny had been fired from his job in the Army Map Service as an astronomer because of his sexual orientation. He had been arrested in California a year earlier for consensual contact with another man. This happened during a time known as the Lavender Scare. Beginning in the late 1940s and continuing through the 1960s, thousands of gay employees were fired or forced to resign from the Federal workforce because of their sexuality. This wave of repression was also bound up with anti-Communism and fueled by the power of congressional investigation.

Kameny sought to have the termination of his employment overturned by the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia. That court did not rule in his favor. Ulitmately, Kameny appealed his firing all the way to the Supreme Court.

In this letter, Kameny appealed to the President and asked for a personal reply. He also enclosed the brief from his Supreme Court case. Kameny wrote:

...the Federal government is the prime offender in depriving the homosexual of his civil and other liberties, and in actively discriminating against him.In 1961, after his appeal to the Supreme Court failed, Kameny co-founded the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C. The group battled anti-gay discrimination in general and the Federal government's exclusionary policies in particular. It was the first gay rights organization in the nation’s capital.

...You have said 'Ask not what can your country do for you, but what can you do for your country.' I know what I can best do for my country, but my country's government, for no sane reason, will not let me do it.

...Let us, as we advance into the Space Age, discard the policies and the attitudes...of the Stone Age.

Kameny became the first openly gay person to testify before Congress in 1963. He did so in defense of Mattachine after Congressman John Dowdy of Texas introduced a bill, H.R. 5990, to try to revoke the organization's permit to operate by amending the existing D.C. Charitable Solicitations Act. Dowdy’s bill stipulated that before granting a fundraising license, the D.C. Board of Commissioners had to certify that the grantee would "benefit or assist in promoting the health, welfare, and the morals of the District of Columbia."

Kameny went on to become a chief organizer of the first gay rights demonstrations in the nation’s capital. In 1965, he led protests at the White House, the Pentagon, and the Civil Service Commission. To remind the country that gay Americans lacked basic civil rights, Kameny and Mattachine joined with other gay rights organizations for "annual reminder" protests at Independence Hall in Philadelphia each Fourth of July from 1965 to 1969. Kameny later ran to become D.C.’s delegate to Congress. He lost the election, but his attempt marked the first time an openly gay candidate had run for Congress.

In 1975, the Civil Service Commission announced new rules stipulating that gay people could no longer be barred or fired from Federal employment because of their sexuality.

This document uses the terms "homosexual" to refer to gay people and "Negro" to refer to Black people – these were commonly accepted in that era, but are outdated and inappropriate today.

Letter from Franklin E. Kameny to President John F. Kennedy

Page 1

Letter from Franklin E. Kameny to President John F. Kennedy

Page 2

Letter from Franklin E. Kameny to President John F. Kennedy

Page 3

Letter from Franklin E. Kameny to President John F. Kennedy

Page 4

Document

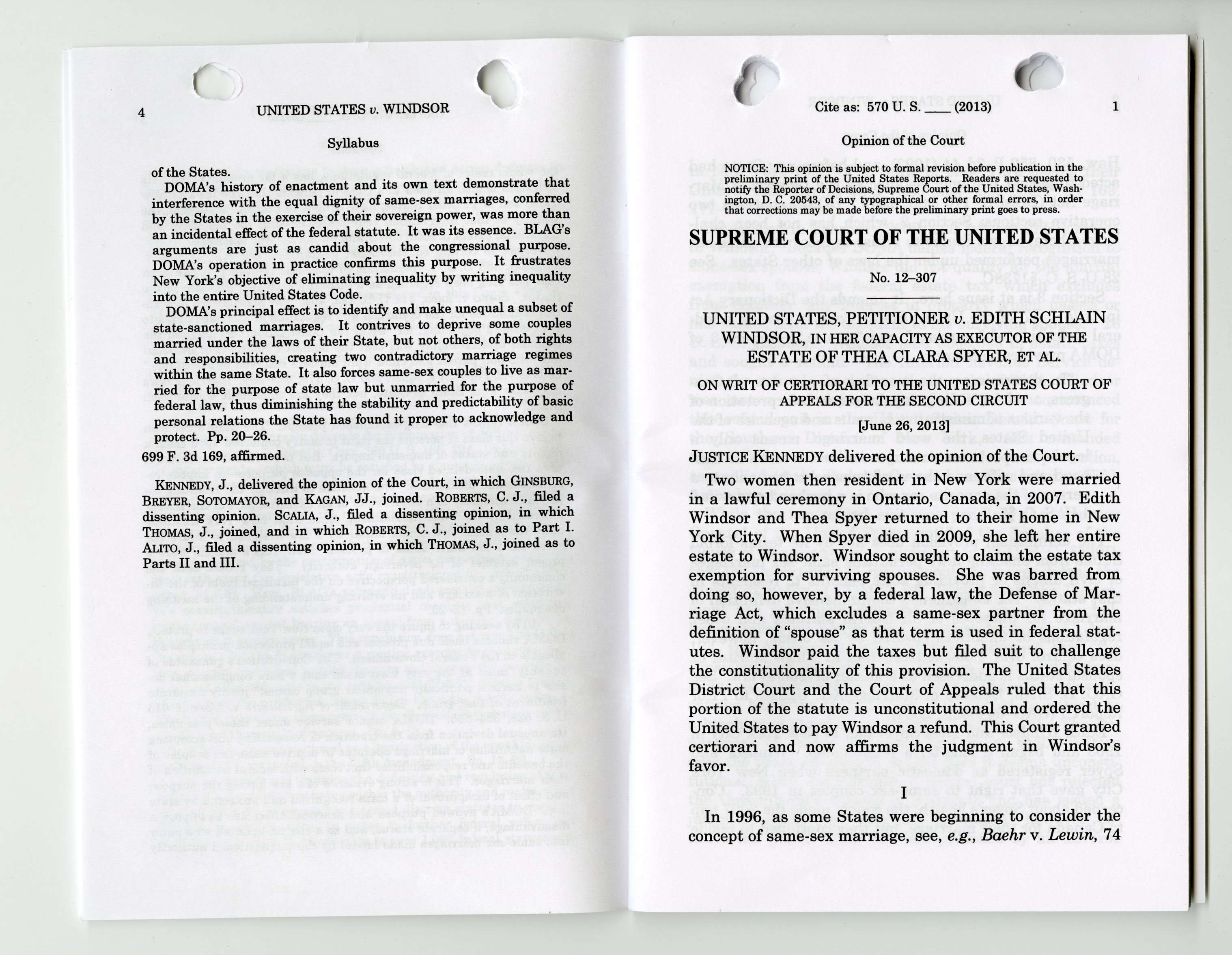

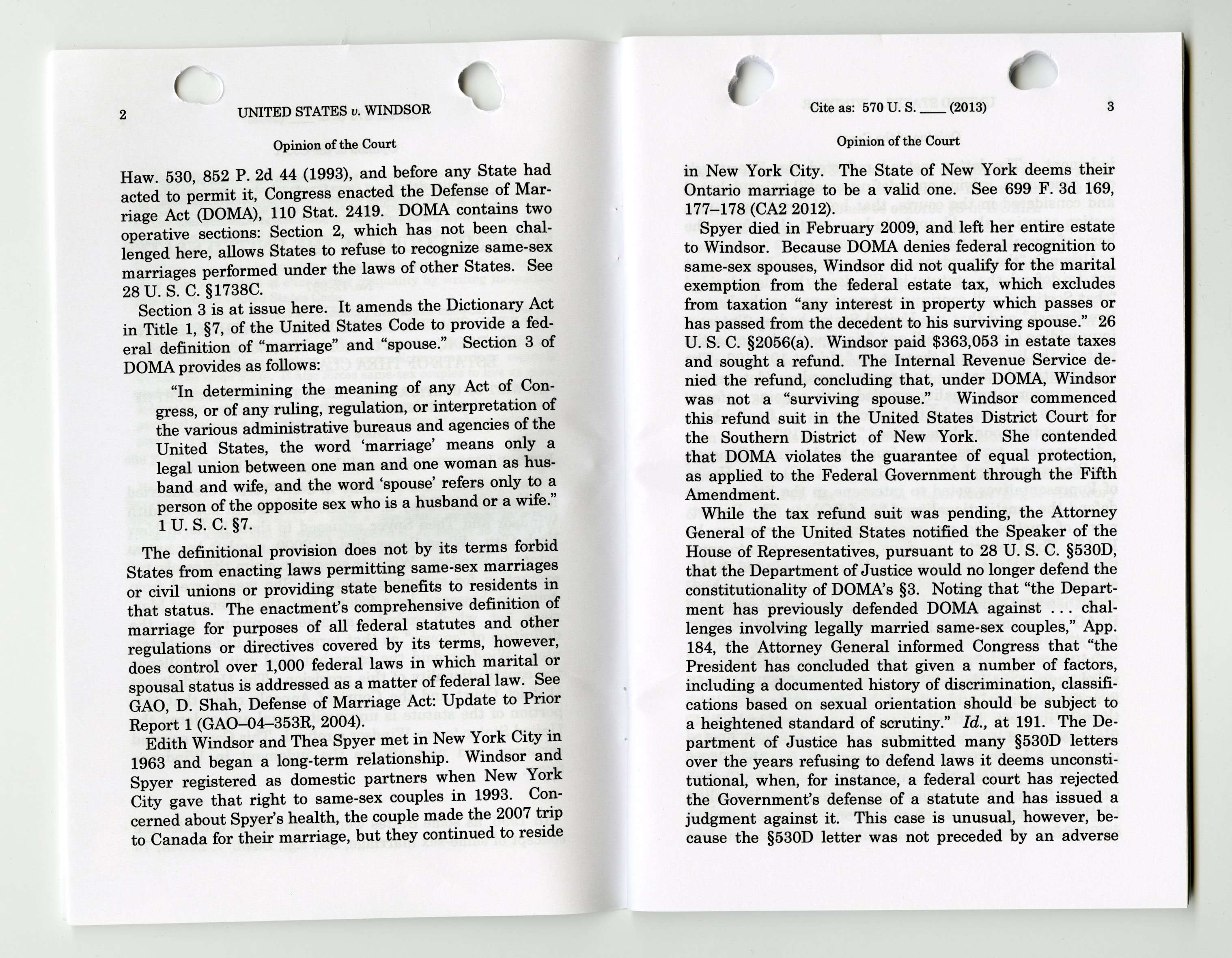

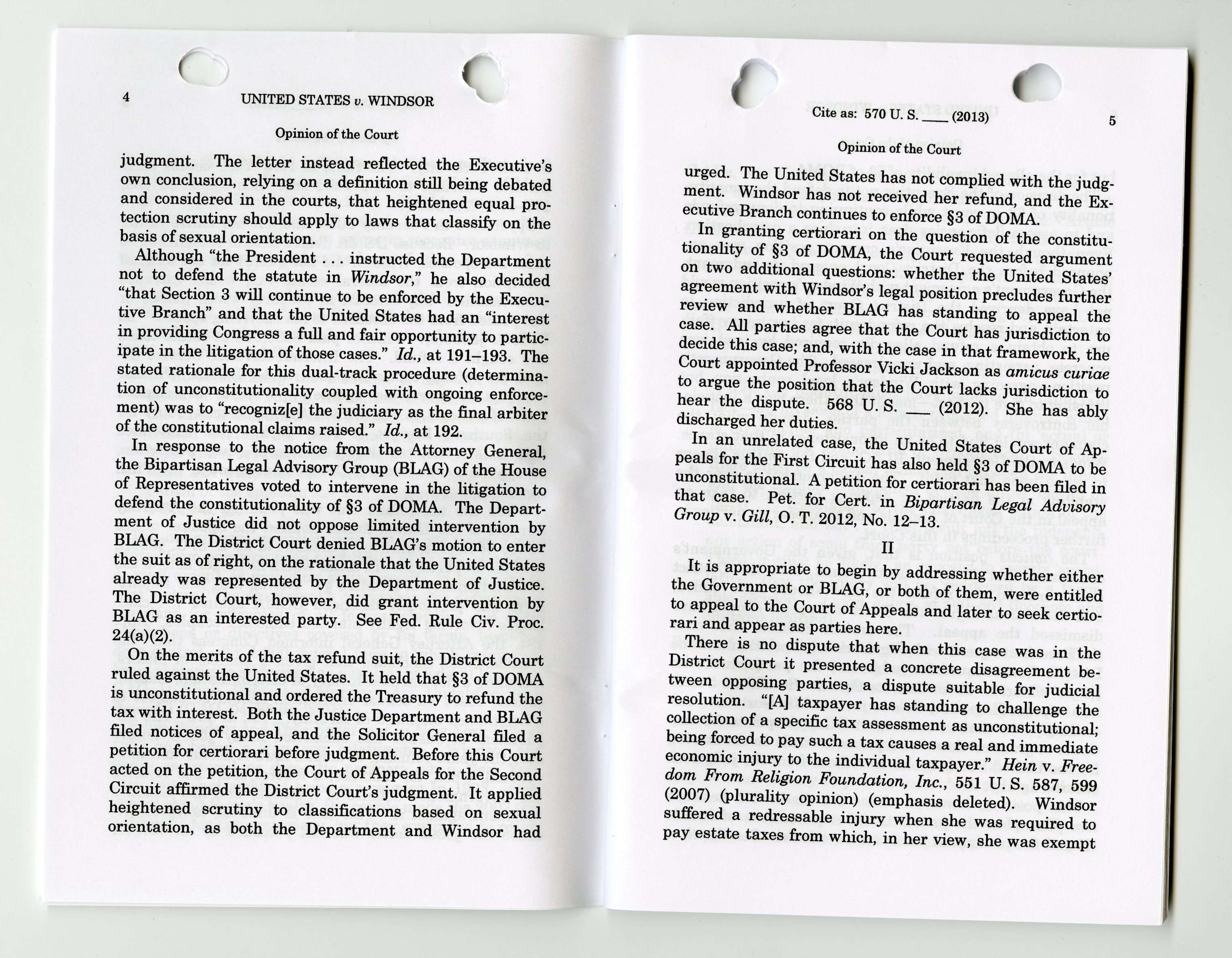

Opinion in U.S. v. Edith Windsor

6/26/2013

In 2010, Edith Windsor sued the Federal Government, claiming that DOMA violated the Equal Protection Clause under the Fifth Amendment. Windsor had been married to Thea Spyer. The two women met in New York City in 1963 and soon after began a long-term relationship. They entered a domestic partnership in 1993, when New York Mayor David Dinkins issued an executive order extending that right to same-sex couples, and were married in Ontario, Canada, in 2007.

When Spyer passed away in 2009 due to a heart condition, Windsor attempted to claim a Federal estate tax exemption for surviving spouses, but the IRS rejected her claims because DOMA held that the term "spouse" only applied to marriages between a man and a woman. As a result, Windsor was forced to pay $363,053 in Federal estate taxes.

Windsor sued for a full refund, arguing DOMA violated the Equal Protection Clause under the Fifth Amendment. The case made its way to the Supreme Court, and on June 26, 2013, the Court ruled in Windsor’s favor, deeming DOMA unconstitutional.

Although it did not legalize same-sex marriage, United States v. Windsor was a milestone in the fight for marriage equality. The decision forced the Federal Government to treat same-sex marriages equally under the law and made tax benefits previously restricted to opposite-sex couples available to same-sex couples. However, this ruling only extended to Federal laws; individual states did not have to recognize same-sex marriages.

This document is the full opinion from the case; the syllabus – a shorter summary added by the Court to help the reader understand the case and decision – is also available. The case also included three dissenting opinions.

Transcript

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, D. C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, in order that corrections may be made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

_________________

No. 12–307

_________________

UNITED STATES, PETITIONER v. EDITH SCHLAIN WINDSOR, in her capacity as executor of the ESTATE OF THEA CLARA SPYER, et al.

on writ of certiorari to the united states court of appeals for the second circuit

[June 26, 2013]

Justice Kennedy delivered the opinion of the Court.

Two women then resident in New York were married in a lawful ceremony in Ontario, Canada, in 2007. Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer returned to their home in New York City. When Spyer died in 2009, she left her entire estate to Windsor. Windsor sought to claim the estate tax exemption for surviving spouses. She was barred from doing so, however, by a federal law, the Defense of Marriage Act, which excludes a same-sex partner from the definition of “spouse” as that term is used in federal statutes. Windsor paid the taxes but filed suit to challenge the constitutionality of this provision. The United States District Court and the Court of Appeals ruled that this portion of the statute is unconstitutional and ordered the United States to pay Windsor a refund. This Court granted certiorari and now affirms the judgment in Windsor’s favor.

I

In 1996, as some States were beginning to consider the concept of same-sex marriage, see, e.g., Baehr v. Lewin, 74 Haw. 530, 852 P. 2d 44 (1993), and before any State had acted to permit it, Congress enacted the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), 110Stat. 2419. DOMA contains two operative sections: Section 2, which has not been challenged here, allows States to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages performed under the laws of other States. See 28 U. S. C. §1738C.

Section 3 is at issue here. It amends the Dictionary Act in Title 1, §7, of the United States Code to provide a fed- eral definition of “marriage” and “spouse.” Section 3 of DOMA provides as follows:

“In determining the meaning of any Act of Congress, or of any ruling, regulation, or interpretation of the various administrative bureaus and agencies of the United States, the word ‘marriage’ means only a legal union between one man and one woman as husband and wife, and the word ‘spouse’ refers only to a person of the opposite sex who is a husband or a wife.” 1 U. S. C. §7.

The definitional provision does not by its terms forbid States from enacting laws permitting same-sex marriages or civil unions or providing state benefits to residents in that status. The enactment’s comprehensive definition of marriage for purposes of all federal statutes and other regulations or directives covered by its terms, however, does control over 1,000 federal laws in which marital or spousal status is addressed as a matter of federal law. See GAO, D. Shah, Defense of Marriage Act: Update to Prior Report 1 (GAO–04–353R, 2004).

Edith Windsor and Thea Spyer met in New York City in 1963 and began a long-term relationship. Windsor and Spyer registered as domestic partners when New York City gave that right to same-sex couples in 1993. Concerned about Spyer’s health, the couple made the 2007 trip to Canada for their marriage, but they continued to reside in New York City. The State of New York deems their Ontario marriage to be a valid one. See 699 F. 3d 169, 177–178 (CA2 2012).

Spyer died in February 2009, and left her entire estate to Windsor. Because DOMA denies federal recognition to same-sex spouses, Windsor did not qualify for the marital exemption from the federal estate tax, which excludes from taxation “any interest in property which passes or has passed from the decedent to his surviving spouse.” 26 U. S. C. §2056(a). Windsor paid $363,053 in estate taxes and sought a refund. The Internal Revenue Service denied the refund, concluding that, under DOMA, Windsor was not a “surviving spouse.” Windsor commenced this refund suit in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. She contended that DOMA violates the guarantee of equal protection, as applied to the Federal Government through the Fifth Amendment.

While the tax refund suit was pending, the Attorney General of the United States notified the Speaker of the House of Representatives, pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §530D, that the Department of Justice would no longer defend the constitutionality of DOMA’s §3. Noting that “the Department has previously defended DOMA against . . . challenges involving legally married same-sex couples,” App. 184, the Attorney General informed Congress that “the President has concluded that given a number of factors, including a documented history of discrimination, classifications based on sexual orientation should be subject to a heightened standard of scrutiny.” Id., at 191. The Department of Justice has submitted many §530D letters over the years refusing to defend laws it deems unconstitutional, when, for instance, a federal court has rejected the Government’s defense of a statute and has issued a judgment against it. This case is unusual, however, because the §530D letter was not preceded by an adverse judgment. The letter instead reflected the Executive’s own conclusion, relying on a definition still being debated and considered in the courts, that heightened equal protection scrutiny should apply to laws that classify on the basis of sexual orientation.

Although “the President . . . instructed the Department not to defend the statute in Windsor,” he also decided “that Section 3 will continue to be enforced by the Executive Branch” and that the United States had an “interest in providing Congress a full and fair opportunity to participate in the litigation of those cases.” Id., at 191–193. The stated rationale for this dual-track procedure (determination of unconstitutionality coupled with ongoing enforcement) was to “recogniz[e] the judiciary as the final arbiter of the constitutional claims raised.” Id., at 192.

In response to the notice from the Attorney General, the Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group (BLAG) of the House of Representatives voted to intervene in the litigation to defend the constitutionality of §3 of DOMA. The Department of Justice did not oppose limited intervention by BLAG. The District Court denied BLAG’s motion to enter the suit as of right, on the rationale that the United States already was represented by the Department of Justice. The District Court, however, did grant intervention by BLAG as an interested party. See Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 24(a)(2).

On the merits of the tax refund suit, the District Court ruled against the United States. It held that §3 of DOMA is unconstitutional and ordered the Treasury to refund the tax with interest. Both the Justice Department and BLAG filed notices of appeal, and the Solicitor General filed a petition for certiorari before judgment. Before this Court acted on the petition, the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit affirmed the District Court’s judgment. It applied heightened scrutiny to classifications based on sexual orientation, as both the Department and Windsor had urged. The United States has not complied with the judg- ment. Windsor has not received her refund, and the Ex- ecutive Branch continues to enforce §3 of DOMA.

In granting certiorari on the question of the constitutionality of §3 of DOMA, the Court requested argument on two additional questions: whether the United States’ agreement with Windsor’s legal position precludes further review and whether BLAG has standing to appeal the case. All parties agree that the Court has jurisdiction to decide this case; and, with the case in that framework, the Court appointed Professor Vicki Jackson as amicus curiae to argue the position that the Court lacks jurisdiction to hear the dispute. 568 U. S. ___ (2012). She has ably discharged her duties.

In an unrelated case, the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit has also held §3 of DOMA to be unconstitutional. A petition for certiorari has been filed in that case. Pet. for Cert. in Bipartisan Legal Advisory Group v. Gill, O. T. 2012, No. 12–13.

II

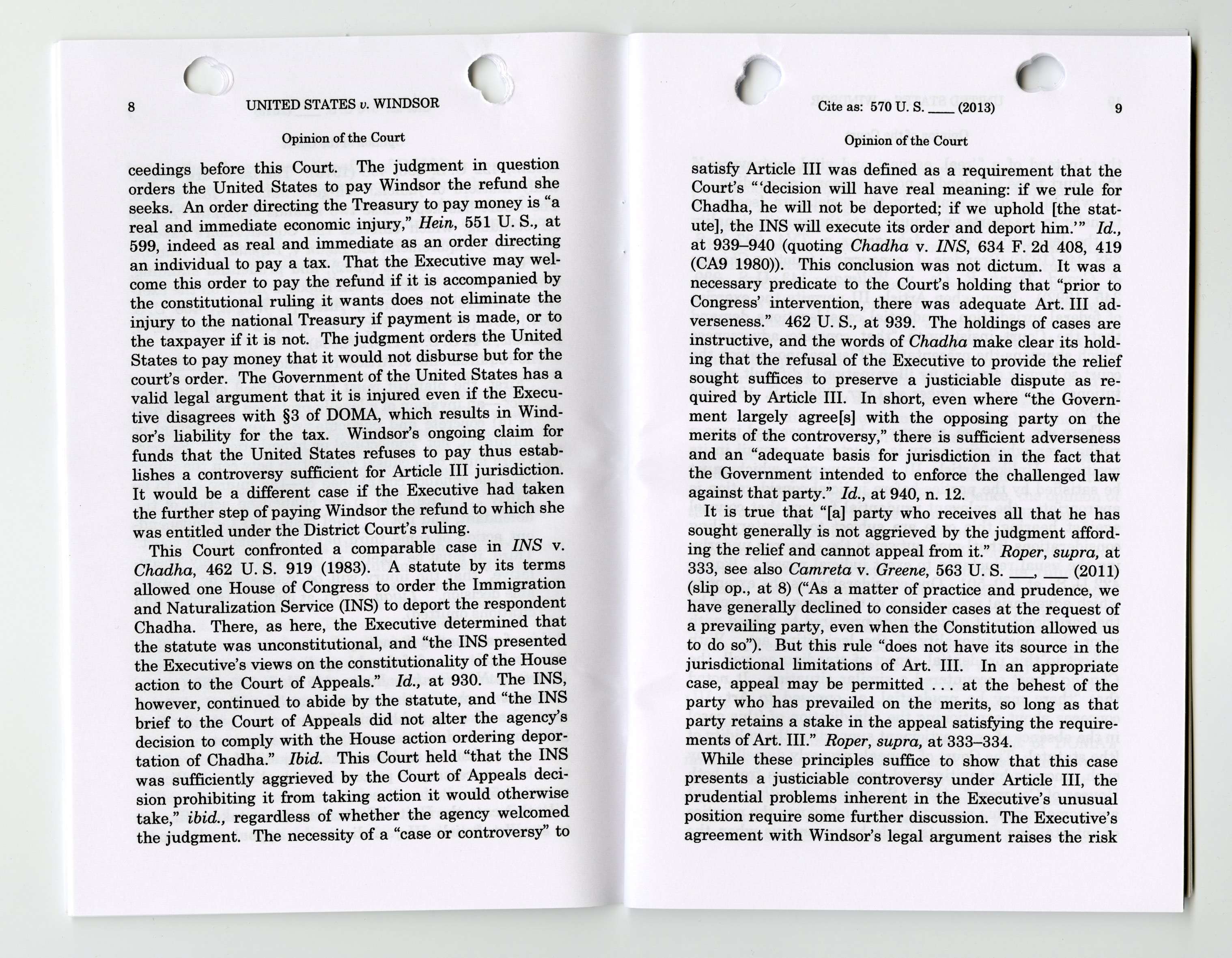

It is appropriate to begin by addressing whether either the Government or BLAG, or both of them, were entitled to appeal to the Court of Appeals and later to seek certiorari and appear as parties here.

There is no dispute that when this case was in the District Court it presented a concrete disagreement between opposing parties, a dispute suitable for judicial resolution. “[A] taxpayer has standing to challenge the collection of a specific tax assessment as unconstitutional; being forced to pay such a tax causes a real and immediate economic injury to the individual taxpayer.” Hein v. Freedom From Religion Foundation, Inc., 551 U. S. 587, 599 (2007) (plurality opinion) (emphasis deleted). Windsor suffered a redressable injury when she was required to pay estate taxes from which, in her view, she was exempt but for the alleged invalidity of §3 of DOMA.

The decision of the Executive not to defend the constitutionality of §3 in court while continuing to deny refunds and to assess deficiencies does introduce a complication. Even though the Executive’s current position was announced before the District Court entered its judgment, the Government’s agreement with Windsor’s position would not have deprived the District Court of jurisdiction to entertain and resolve the refund suit; for her injury (fail- ure to obtain a refund allegedly required by law) was concrete, persisting, and unredressed. The Government’s position—agreeing with Windsor’s legal contention but refusing to give it effect—meant that there was a justiciable controversy between the parties, despite what the claimant would find to be an inconsistency in that stance. Windsor, the Government, BLAG, and the amicus appear to agree upon that point. The disagreement is over the standing of the parties, or aspiring parties, to take an appeal in the Court of Appeals and to appear as parties in further proceedings in this Court.

The amicus’ position is that, given the Government’s concession that §3 is unconstitutional, once the District Court ordered the refund the case should have ended; and the amicus argues the Court of Appeals should have dismissed the appeal. The amicus submits that once the President agreed with Windsor’s legal position and the District Court issued its judgment, the parties were no longer adverse. From this standpoint the United States was a prevailing party below, just as Windsor was. Accordingly, the amicus reasons, it is inappropriate for this Court to grant certiorari and proceed to rule on the merits; for the United States seeks no redress from the judgment entered against it.

This position, however, elides the distinction between two principles: the jurisdictional requirements of Article III and the prudential limits on its exercise. See Warth v. Seldin, 422 U. S. 490, 498 (1975) . The latter are “essentially matters of judicial self-governance.” Id., at 500. The Court has kept these two strands separate: “Article III standing, which enforces the Constitution’s case-or-controversy requirement, see Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U. S. 555 –562 (1992); and prudential standing, which embodies ‘judicially self-imposed limits on the exer- cise of federal jurisdiction,’ Allen [v. Wright,] 468 U. S. [737,] 751 [(1984)].” Elk Grove Unified School Dist. v. Newdow, 542 U. S. 1 –12 (2004).

The requirements of Article III standing are familiar:

“First, the plaintiff must have suffered an ‘injury in fact’—an invasion of a legally protected interest which is (a) concrete and particularized, and (b) ‘actual or imminent, not “conjectural or hypothetical.” ’ Second, there must be a causal connection between the injury and the conduct complained of—the injury has to be ‘fairly . . . trace[able] to the challenged action of the defendant, and not . . . th[e] result [of] the independent action of some third party not before the court.’ Third, it must be ‘likely,’ as opposed to merely ‘speculative,’ that the injury will be ‘redressed by a favor- able decision.’ ” Lujan, supra, at 560–561 (footnote and citations omitted).

Rules of prudential standing, by contrast, are more flex- ible “rule[s] . . . of federal appellate practice,” Deposit Guaranty Nat. Bank v. Roper, 445 U. S. 326, 333 (1980) , designed to protect the courts from “decid[ing] abstract questions of wide public significance even [when] other governmental institutions may be more competent to ad- dress the questions and even though judicial intervention may be unnecessary to protect individual rights.” Warth, supra, at 500.

In this case the United States retains a stake sufficient to support Article III jurisdiction on appeal and in proceedings before this Court. The judgment in question orders the United States to pay Windsor the refund she seeks. An order directing the Treasury to pay money is “a real and immediate economic injury,” Hein, 551 U. S., at 599, indeed as real and immediate as an order directing an individual to pay a tax. That the Executive may welcome this order to pay the refund if it is accompanied by the constitutional ruling it wants does not eliminate the injury to the national Treasury if payment is made, or to the taxpayer if it is not. The judgment orders the United States to pay money that it would not disburse but for the court’s order. The Government of the United States has a valid legal argument that it is injured even if the Executive disagrees with §3 of DOMA, which results in Windsor’s liability for the tax. Windsor’s ongoing claim for funds that the United States refuses to pay thus establishes a controversy sufficient for Article III jurisdiction. It would be a different case if the Executive had taken the further step of paying Windsor the refund to which she was entitled under the District Court’s ruling.

This Court confronted a comparable case in INS v. Chadha, 462 U. S. 919 (1983) . A statute by its terms allowed one House of Congress to order the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) to deport the respondent Chadha. There, as here, the Executive determined that the statute was unconstitutional, and “the INS presented the Executive’s views on the constitutionality of the House action to the Court of Appeals.” Id., at 930. The INS, however, continued to abide by the statute, and “the INS brief to the Court of Appeals did not alter the agency’s decision to comply with the House action ordering deportation of Chadha.” Ibid. This Court held “that the INS was sufficiently aggrieved by the Court of Appeals deci- sion prohibiting it from taking action it would otherwise take,” ibid., regardless of whether the agency welcomed the judgment. The necessity of a “case or controversy” to satisfy Article III was defined as a requirement that the Court’s “ ‘decision will have real meaning: if we rule for Chadha, he will not be deported; if we uphold [the statute], the INS will execute its order and deport him.’ ” Id., at 939–940 (quoting Chadha v. INS, 634 F. 2d 408, 419 (CA9 1980)). This conclusion was not dictum. It was a necessary predicate to the Court’s holding that “prior to Congress’ intervention, there was adequate Art. III adverseness.” 462 U. S., at 939. The holdings of cases are instructive, and the words of Chadha make clear its holding that the refusal of the Executive to provide the relief sought suffices to preserve a justiciable dispute as required by Article III. In short, even where “the Government largely agree[s] with the opposing party on the merits of the controversy,” there is sufficient adverseness and an “adequate basis for jurisdiction in the fact that the Government intended to enforce the challenged law against that party.” Id., at 940, n. 12.

It is true that “[a] party who receives all that he has sought generally is not aggrieved by the judgment affording the relief and cannot appeal from it.” Roper, supra, at 333, see also Camreta v. Greene, 563 U. S. ___, ___ (2011) (slip op., at 8) (“As a matter of practice and prudence, we have generally declined to consider cases at the request of a prevailing party, even when the Constitution allowed us to do so”). But this rule “does not have its source in the jurisdictional limitations of Art. III. In an appropriate case, appeal may be permitted . . . at the behest of the party who has prevailed on the merits, so long as that party retains a stake in the appeal satisfying the requirements of Art. III.” Roper, supra, at 333–334.

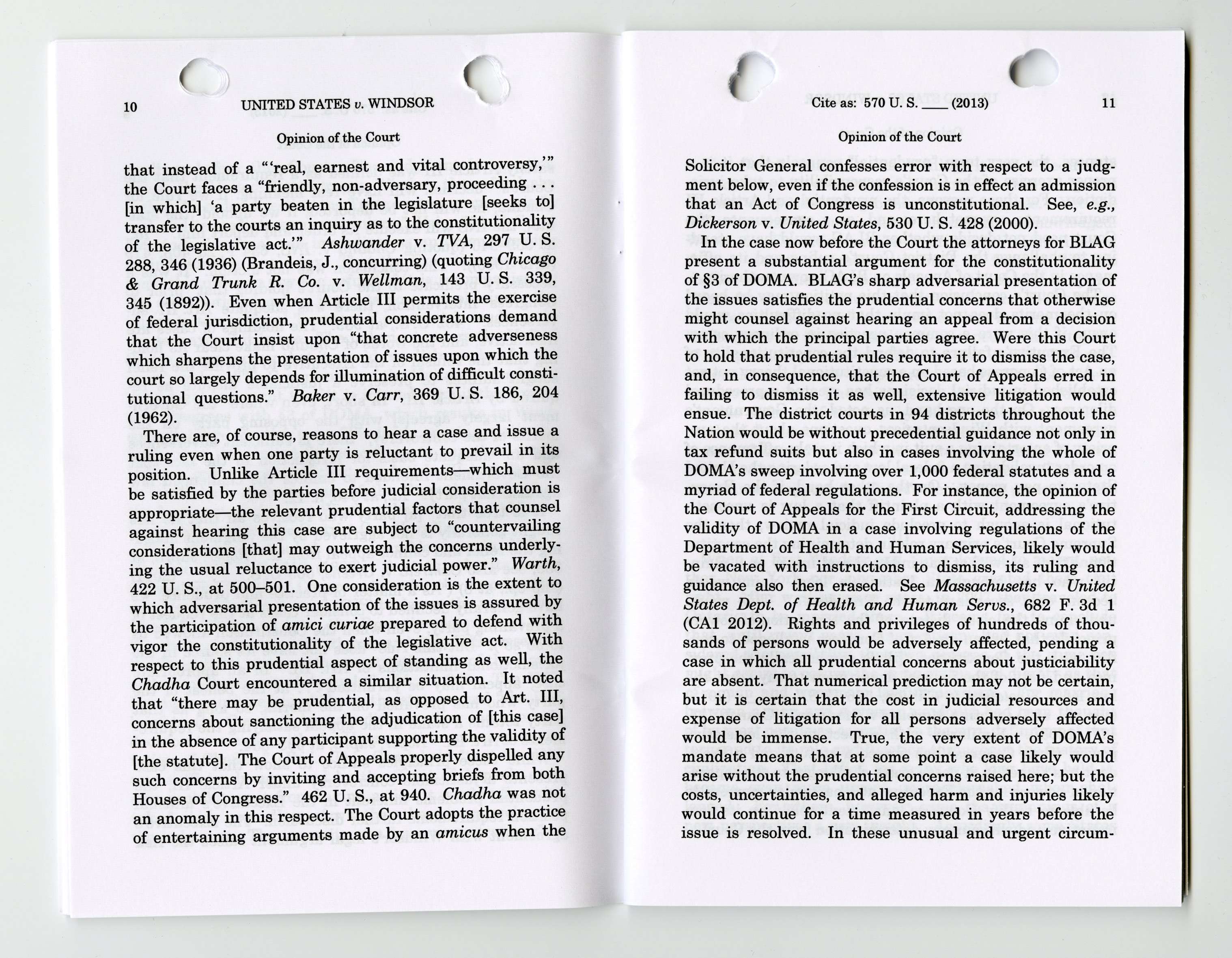

While these principles suffice to show that this case presents a justiciable controversy under Article III, the prudential problems inherent in the Executive’s unusual position require some further discussion. The Executive’s agreement with Windsor’s legal argument raises the risk that instead of a “ ‘real, earnest and vital controversy,’ ” the Court faces a “friendly, non-adversary, proceeding . . . [in which] ‘a party beaten in the legislature [seeks to] transfer to the courts an inquiry as to the constitutionality of the legislative act.’ ” Ashwander v. TVA, 297 U. S. 288, 346 (1936) (Brandeis, J., concurring) (quoting Chicago & Grand Trunk R. Co. v. Wellman, 143 U. S. 339, 345 (1892) ). Even when Article III permits the exercise of federal jurisdiction, prudential considerations demand that the Court insist upon “that concrete adverseness which sharpens the presentation of issues upon which the court so largely depends for illumination of difficult constitutional questions.” Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186, 204 (1962) .

There are, of course, reasons to hear a case and issue a ruling even when one party is reluctant to prevail in its position. Unlike Article III requirements—which must be satisfied by the parties before judicial consideration is appropriate—the relevant prudential factors that counsel against hearing this case are subject to “countervailing considerations [that] may outweigh the concerns underlying the usual reluctance to exert judicial power.” Warth, 422 U. S., at 500–501. One consideration is the extent to which adversarial presentation of the issues is assured by the participation of amici curiae prepared to defend with vigor the constitutionality of the legislative act. With respect to this prudential aspect of standing as well, the Chadha Court encountered a similar situation. It noted that “there may be prudential, as opposed to Art. III, concerns about sanctioning the adjudication of [this case] in the absence of any participant supporting the validity of [the statute]. The Court of Appeals properly dispelled any such concerns by inviting and accepting briefs from both Houses of Congress.” 462 U. S., at 940. Chadha was not an anomaly in this respect. The Court adopts the practice of entertaining arguments made by an amicus when the Solicitor General confesses error with respect to a judgment below, even if the confession is in effect an admission that an Act of Congress is unconstitutional. See, e.g., Dickerson v. United States, 530 U. S. 428 (2000) .

In the case now before the Court the attorneys for BLAG present a substantial argument for the constitutionality of §3 of DOMA. BLAG’s sharp adversarial presentation of the issues satisfies the prudential concerns that otherwise might counsel against hearing an appeal from a decision with which the principal parties agree. Were this Court to hold that prudential rules require it to dismiss the case, and, in consequence, that the Court of Appeals erred in failing to dismiss it as well, extensive litigation would ensue. The district courts in 94 districts throughout the Nation would be without precedential guidance not only in tax refund suits but also in cases involving the whole of DOMA’s sweep involving over 1,000 federal statutes and a myriad of federal regulations. For instance, the opinion of the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit, addressing the validity of DOMA in a case involving regulations of the Department of Health and Human Services, likely would be vacated with instructions to dismiss, its ruling and guidance also then erased. See Massachusetts v. United States Dept. of Health and Human Servs., 682 F. 3d 1 (CA1 2012). Rights and privileges of hundreds of thousands of persons would be adversely affected, pending a case in which all prudential concerns about justiciability are absent. That numerical prediction may not be certain, but it is certain that the cost in judicial resources and expense of litigation for all persons adversely affected would be immense. True, the very extent of DOMA’s mandate means that at some point a case likely would arise without the prudential concerns raised here; but the costs, uncertainties, and alleged harm and injuries likely would continue for a time measured in years before the issue is resolved. In these unusual and urgent circumstances, the very term “prudential” counsels that it is a proper exercise of the Court’s responsibility to take jurisdiction. For these reasons, the prudential and Article III requirements are met here; and, as a consequence, the Court need not decide whether BLAG would have standing to challenge the District Court’s ruling and its affirmance in the Court of Appeals on BLAG’s own authority.

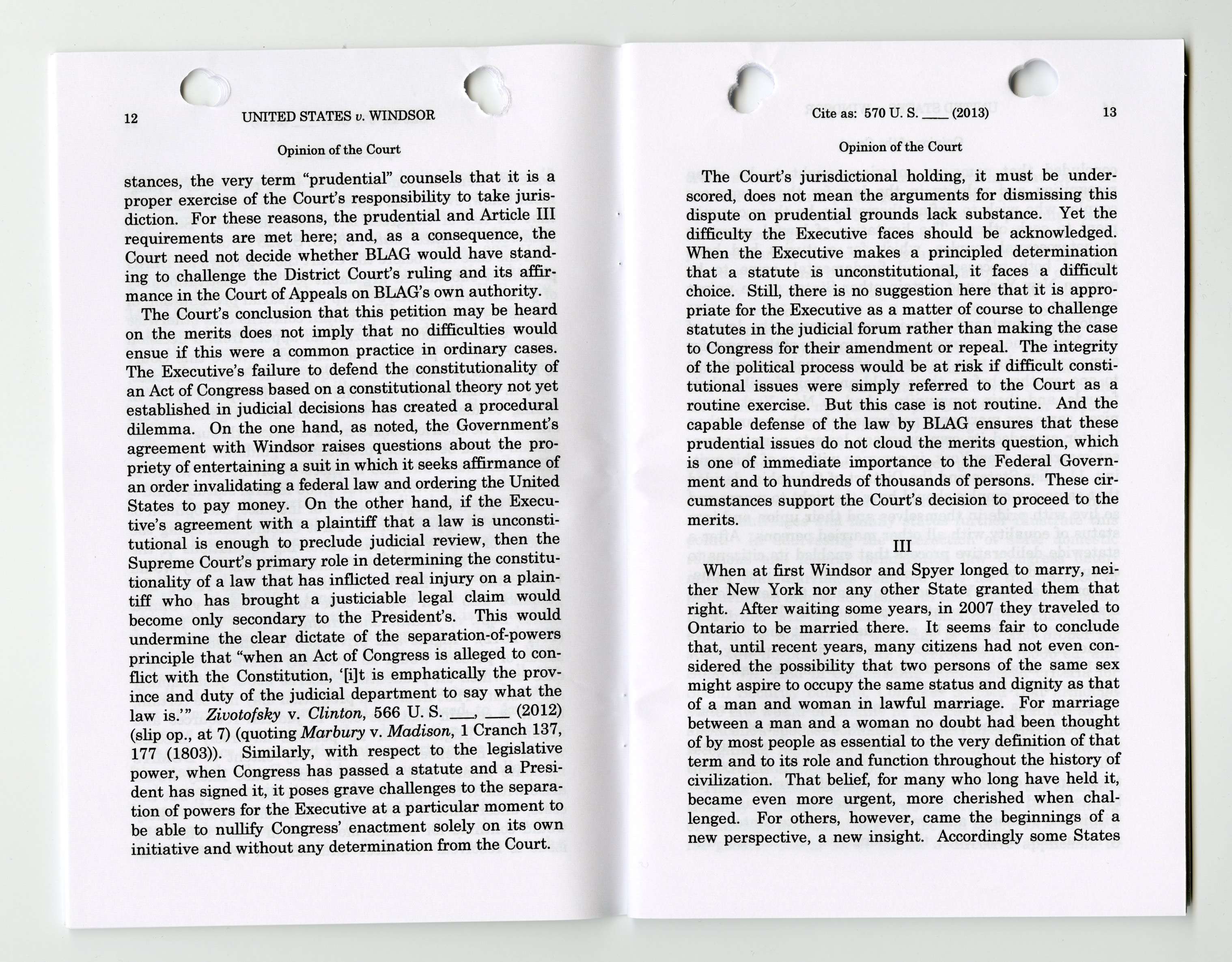

The Court’s conclusion that this petition may be heard on the merits does not imply that no difficulties would ensue if this were a common practice in ordinary cases. The Executive’s failure to defend the constitutionality of an Act of Congress based on a constitutional theory not yet established in judicial decisions has created a procedural dilemma. On the one hand, as noted, the Government’s agreement with Windsor raises questions about the propriety of entertaining a suit in which it seeks affirmance of an order invalidating a federal law and ordering the United States to pay money. On the other hand, if the Execu- tive’s agreement with a plaintiff that a law is unconsti- tutional is enough to preclude judicial review, then the Supreme Court’s primary role in determining the constitutionality of a law that has inflicted real injury on a plaintiff who has brought a justiciable legal claim would become only secondary to the President’s. This would undermine the clear dictate of the separation-of-powers principle that “when an Act of Congress is alleged to conflict with the Constitution, ‘[i]t is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.’ ” Zivotofsky v. Clinton, 566 U. S. ___, ___ (2012) (slip op., at 7) (quoting Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 177 (1803)). Similarly, with respect to the legislative power, when Congress has passed a statute and a President has signed it, it poses grave challenges to the separation of powers for the Executive at a particular moment to be able to nullify Congress’ enactment solely on its own initiative and without any determination from the Court.

The Court’s jurisdictional holding, it must be underscored, does not mean the arguments for dismissing this dispute on prudential grounds lack substance. Yet the difficulty the Executive faces should be acknowledged. When the Executive makes a principled determination that a statute is unconstitutional, it faces a difficult choice. Still, there is no suggestion here that it is appropriate for the Executive as a matter of course to challenge statutes in the judicial forum rather than making the case to Congress for their amendment or repeal. The integrity of the political process would be at risk if difficult consti- tutional issues were simply referred to the Court as a routine exercise. But this case is not routine. And the capable defense of the law by BLAG ensures that these prudential issues do not cloud the merits question, which is one of immediate importance to the Federal Government and to hundreds of thousands of persons. These cir- cumstances support the Court’s decision to proceed to the merits.

III

When at first Windsor and Spyer longed to marry, neither New York nor any other State granted them that right. After waiting some years, in 2007 they traveled to Ontario to be married there. It seems fair to conclude that, until recent years, many citizens had not even considered the possibility that two persons of the same sex might aspire to occupy the same status and dignity as that of a man and woman in lawful marriage. For marriage between a man and a woman no doubt had been thought of by most people as essential to the very definition of that term and to its role and function throughout the history of civilization. That belief, for many who long have held it, became even more urgent, more cherished when challenged. For others, however, came the beginnings of a new perspective, a new insight. Accordingly some States concluded that same-sex marriage ought to be given recognition and validity in the law for those same-sex couples who wish to define themselves by their commitment to each other. The limitation of lawful marriage to heterosexual couples, which for centuries had been deemed both necessary and fundamental, came to be seen in New York and certain other States as an unjust exclusion.

Slowly at first and then in rapid course, the laws of New York came to acknowledge the urgency of this issue for same-sex couples who wanted to affirm their commitment to one another before their children, their family, their friends, and their community. And so New York recognized same-sex marriages performed elsewhere; and then it later amended its own marriage laws to permit same-sex marriage. New York, in common with, as of this writing, 11 other States and the District of Columbia, decided that same-sex couples should have the right to marry and so live with pride in themselves and their union and in a status of equality with all other married persons. After a statewide deliberative process that enabled its citizens to discuss and weigh arguments for and against same- sex marriage, New York acted to enlarge the definition of marriage to correct what its citizens and elected representatives perceived to be an injustice that they had not earlier known or understood. See Marriage Equality Act, 2011 N. Y. Laws 749 (codified at N. Y. Dom. Rel. Law Ann. §§10–a, 10–b, 13 (West 2013)).

Against this background of lawful same-sex marriage in some States, the design, purpose, and effect of DOMA should be considered as the beginning point in deciding whether it is valid under the Constitution. By history and tradition the definition and regulation of marriage, as will be discussed in more detail, has been treated as being within the authority and realm of the separate States. Yet it is further established that Congress, in enacting discrete statutes, can make determinations that bear on marital rights and privileges. Just this Term the Court upheld the authority of the Congress to pre-empt state laws, allowing a former spouse to retain life insurance proceeds under a federal program that gave her priority, because of formal beneficiary designation rules, over the wife by a second marriage who survived the husband. Hillman v. Maretta, 569 U. S. ___ (2013); see also Ridgway v. Ridgway, 454 U. S. 46 (1981) ; Wissner v. Wissner, 338 U. S. 655 (1950) . This is one example of the general principle that when the Federal Government acts in the exercise of its own proper authority, it has a wide choice of the mechanisms and means to adopt. See McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316, 421 (1819). Congress has the power both to ensure efficiency in the administration of its programs and to choose what larger goals and policies to pursue.

Other precedents involving congressional statutes which affect marriages and family status further illustrate this point. In addressing the interaction of state domestic relations and federal immigration law Congress determined that marriages “entered into for the purpose of procuring an alien’s admission [to the United States] as an immigrant” will not qualify the noncitizen for that status, even if the noncitizen’s marriage is valid and proper for state-law purposes. 8 U. S. C. §1186a(b)(1) (2006 ed. and Supp. V). And in establishing income-based criteria for Social Security benefits, Congress decided that although state law would determine in general who qualifies as an applicant’s spouse, common-law marriages also should be recognized, regardless of any particular State’s view on these relationships. 42 U. S. C. §1382c(d)(2).

Though these discrete examples establish the constitutionality of limited federal laws that regulate the meaning of marriage in order to further federal policy, DOMA has a far greater reach; for it enacts a directive applicable to over 1,000 federal statutes and the whole realm of federal regulations. And its operation is directed to a class of persons that the laws of New York, and of 11 other States, have sought to protect. See Goodridge v. Department of Public Health, 440 Mass. 309, 798 N. E. 2d 941 (2003); An Act Implementing the Guarantee of Equal Protection Under the Constitution of the State for Same Sex Couples, 2009 Conn. Pub. Acts no. 09–13; Varnum v. Brien, 763 N. W. 2d 862 (Iowa 2009); Vt. Stat. Ann., Tit. 15, §8 (2010); N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §457:1–a (West Supp. 2012); Religious Freedom and Civil Marriage Equality Amendment Act of 2009, 57 D. C. Reg. 27 (Dec. 18, 2009); N. Y. Dom. Rel. Law Ann. §10–a (West Supp. 2013); Wash. Rev. Code §26.04.010 (2012); Citizen Initiative, Same- Sex Marriage, Question 1 (Me. 2012) (results online at http: / / w w w.maine.gov/sos/cec/elec/2012/tab - ref-2012.html (all Internet sources as visited June 18, 2013, and avail- able in Clerk of Court’s case file)); Md. Fam. Law Code Ann. §2–201 (Lexis 2012); An Act to Amend Title 13 of the Delaware Code Relating to Domestic Relations to Provide for Same-Gender Civil Marriage and to Convert Exist- ing Civil Unions to Civil Marriages, 79 Del. Laws ch. 19 (2013); An act relating to marriage; providing for civil marriage between two persons; providing for exemptions and protections based on religious association, 2013 Minn. Laws ch. 74; An Act Relating to Domestic Relations—Persons Eligible to Marry, 2013 R. I. Laws ch. 4.

In order to assess the validity of that intervention it is necessary to discuss the extent of the state power and au- thority over marriage as a matter of history and tradi- tion. State laws defining and regulating marriage, of course, must respect the constitutional rights of persons, see, e.g., Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S. 1 (1967) ; but, subject to those guarantees, “regulation of domestic relations” is “an area that has long been regarded as a virtually exclusive province of the States.” Sosna v. Iowa, 419 U. S. 393, 404 (1975) .

The recognition of civil marriages is central to state domestic relations law applicable to its residents and citizens. See Williams v. North Carolina, 317 U. S. 287, 298 (1942) (“Each state as a sovereign has a rightful and legitimate concern in the marital status of persons domiciled within its borders”). The definition of marriage is the foundation of the State’s broader authority to regulate the subject of domestic relations with respect to the “[p]rotection of offspring, property interests, and the enforcement of marital responsibilities.” Ibid. “[T]he states, at the time of the adoption of the Constitution, possessed full power over the subject of marriage and divorce . . . [and] the Constitution delegated no authority to the Government of the United States on the subject of marriage and divorce.” Haddock v. Haddock, 201 U. S. 562, 575 (1906) ; see also In re Burrus, 136 U. S. 586 –594 (1890) (“The whole subject of the domestic relations of husband and wife, parent and child, belongs to the laws of the States and not to the laws of the United States”).

Consistent with this allocation of authority, the Federal Government, through our history, has deferred to state-law policy decisions with respect to domestic relations. In De Sylva v. Ballentine, 351 U. S. 570 (1956) , for example, the Court held that, “[t]o decide who is the widow or widower of a deceased author, or who are his executors or next of kin,” under the Copyright Act “requires a reference to the law of the State which created those legal relationships” because “there is no federal law of domestic relations.” Id., at 580. In order to respect this principle, the federal courts, as a general rule, do not adjudicate issues of marital status even when there might otherwise be a basis for federal jurisdiction. See Ankenbrandt v. Richards, 504 U. S. 689, 703 (1992) . Federal courts will not hear divorce and custody cases even if they arise in diversity because of “the virtually exclusive primacy . . . of the States in the regulation of domestic relations.” Id., at 714 (Blackmun, J., concurring in judgment).

The significance of state responsibilities for the definition and regulation of marriage dates to the Nation’s beginning; for “when the Constitution was adopted the common understanding was that the domestic relations of husband and wife and parent and child were matters reserved to the States.” Ohio ex rel. Popovici v. Agler, 280 U. S. 379 –384 (1930). Marriage laws vary in some respects from State to State. For example, the required minimum age is 16 in Vermont, but only 13 in New Hampshire. Compare Vt. Stat. Ann., Tit. 18, §5142 (2012), with N. H. Rev. Stat. Ann. §457:4 (West Supp. 2012). Likewise the permissible degree of consanguinity can vary (most States permit first cousins to marry, but a handful—such as Iowa and Washington, see Iowa Code §595.19 (2009); Wash. Rev. Code §26.04.020 (2012)—prohibit the practice). But these rules are in every event consistent within each State.

Against this background DOMA rejects the long-established precept that the incidents, benefits, and obligations of marriage are uniform for all married couples within each State, though they may vary, subject to constitutional guarantees, from one State to the next. Despite these considerations, it is unnecessary to decide whether this federal intrusion on state power is a violation of the Constitution because it disrupts the federal balance. The State’s power in defining the marital relation is of central relevance in this case quite apart from principles of federalism. Here the State’s decision to give this class of persons the right to marry conferred upon them a dignity and status of immense import. When the State used its historic and essential authority to define the marital relation in this way, its role and its power in making the decision enhanced the recognition, dignity, and protection of the class in their own community. DOMA, because of its reach and extent, departs from this history and tra- dition of reliance on state law to define marriage. “ ‘[D]is-criminations of an unusual character especially sug- gest careful consideration to determine whether they are obnoxious to the constitutional provision.’ ” Romer v. Evans, 517 U. S. 620, 633 (1996) (quoting Louisville Gas & Elec. Co. v. Coleman, 277 U. S. 32 –38 (1928)).

The Federal Government uses this state-defined class for the opposite purpose—to impose restrictions and dis- abilities. That result requires this Court now to address whether the resulting injury and indignity is a deprivation of an essential part of the liberty protected by the Fifth Amendment. What the State of New York treats as alike the federal law deems unlike by a law designed to injure the same class the State seeks to protect.

In acting first to recognize and then to allow same-sex marriages, New York was responding “to the initiative of those who [sought] a voice in shaping the destiny of their own times.” Bond v. United States, 564 U. S. ___, ___ (2011) (slip op., at 9). These actions were without doubt a proper exercise of its sovereign authority within our fed- eral system, all in the way that the Framers of the Constitu-tion intended. The dynamics of state government in the federal system are to allow the formation of consensus respecting the way the members of a discrete community treat each other in their daily contact and constant interaction with each other.

The States’ interest in defining and regulating the marital relation, subject to constitutional guarantees, stems from the understanding that marriage is more than a routine classification for purposes of certain statutory benefits. Private, consensual sexual intimacy between two adult persons of the same sex may not be punished by the State, and it can form “but one element in a personal bond that is more enduring.” Lawrence v. Texas, 539 U. S. 558, 567 (2003) . By its recognition of the validity of same-sex marriages performed in other jurisdictions and then by authorizing same-sex unions and same-sex marriages, New York sought to give further protection and dignity to that bond. For same-sex couples who wished to be married, the State acted to give their lawful conduct a lawful status. This status is a far-reaching legal acknowledgment of the intimate relationship between two people, a relationship deemed by the State worthy of dignity in the community equal with all other marriages. It reflects both the community’s considered perspective on the historical roots of the institution of marriage and its evolving understanding of the meaning of equality.

IV

DOMA seeks to injure the very class New York seeks to protect. By doing so it violates basic due process and equal protection principles applicable to the Federal Government. See U. S. Const., Amdt. 5; Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 (1954) . The Constitution’s guarantee of equality “must at the very least mean that a bare con- gressional desire to harm a politically unpopular group cannot” justify disparate treatment of that group. Depart- ment of Agriculture v. Moreno, 413 U. S. 528 –535 (1973). In determining whether a law is motived by an improper animus or purpose, “ ‘[d]iscriminations of an un- usual character’ ” especially require careful considera- tion. Supra, at 19 (quoting Romer, supra, at 633). DOMA cannot survive under these principles. The responsibility of the States for the regulation of domestic relations is an important indicator of the substantial societal impact the State’s classifications have in the daily lives and customs of its people. DOMA’s unusual deviation from the usual tradition of recognizing and accepting state definitions of marriage here operates to deprive same-sex couples of the benefits and responsibilities that come with the federal recognition of their marriages. This is strong evidence of a law having the purpose and effect of disapproval of that class. The avowed purpose and practical effect of the law here in question are to impose a disadvantage, a separate status, and so a stigma upon all who enter into same-sex marriages made lawful by the unquestioned authority of the States.

The history of DOMA’s enactment and its own text demonstrate that interference with the equal dignity of same-sex marriages, a dignity conferred by the States in the exercise of their sovereign power, was more than an incidental effect of the federal statute. It was its essence. The House Report announced its conclusion that “it is both appropriate and necessary for Congress to do what it can to defend the institution of traditional heterosexual marriage. . . . H. R. 3396 is appropriately entitled the ‘Defense of Marriage Act.’ The effort to redefine ‘marriage’ to extend to homosexual couples is a truly radical proposal that would fundamentally alter the institution of marriage.” H. R. Rep. No. 104–664, pp. 12–13 (1996). The House concluded that DOMA expresses “both moral disapproval of homosexuality, and a moral conviction that heterosexuality better comports with traditional (especially Judeo-Christian) morality.” Id., at 16 (footnote deleted). The stated purpose of the law was to promote an “interest in protecting the traditional moral teachings reflected in heterosexual-only marriage laws.” Ibid. Were there any doubt of this far-reaching purpose, the title of the Act confirms it: The Defense of Marriage.

The arguments put forward by BLAG are just as candid about the congressional purpose to influence or interfere with state sovereign choices about who may be married. As the title and dynamics of the bill indicate, its purpose is to discourage enactment of state same-sex marriage laws and to restrict the freedom and choice of couples married under those laws if they are enacted. The congressional goal was “to put a thumb on the scales and influence a state’s decision as to how to shape its own marriage laws.” Massachusetts, 682 F. 3d, at 12–13. The Act’s demonstrated purpose is to ensure that if any State decides to recognize same-sex marriages, those unions will be treated as second-class marriages for purposes of federal law. This raises a most serious question under the Constitution’s Fifth Amendment.

DOMA’s operation in practice confirms this purpose. When New York adopted a law to permit same-sex marriage, it sought to eliminate inequality; but DOMA frustrates that objective through a system-wide enactment with no identified connection to any particular area of fed- eral law. DOMA writes inequality into the entire United States Code. The particular case at hand concerns the estate tax, but DOMA is more than a simple determi- nation of what should or should not be allowed as an estate tax refund. Among the over 1,000 statutes and numerous federal regulations that DOMA controls are laws pertaining to Social Security, housing, taxes, criminal sanctions, copyright, and veterans’ benefits.