To What Extent was Reconstruction a Revolution? (Part 1)

Weighing the Evidence

All documents and text associated with this activity are printed below, followed by a worksheet for student responses.Introduction

To what extent was Reconstruction a revolution? After the Civil War, there were many changes throughout the country, especially relating to the rights of the newly freed slaves. But some features of society ended up not really changing much at all.In this activity, you will investigate these changes by analyzing historical congressional records relating to the rights of African Americans and organizing the evidence by placing the documents on the scale according to which interpretation they support. The documents used in this activity come from the historical records records of the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives.

Name:

Class:

Class:

Worksheet

To What Extent was Reconstruction a Revolution? (Part 1)

Weighing the Evidence

Examine the documents and text included in this activity. Consider how each document does or does not support two opposing interpretations or conclusions. Fill in the topic or interpretations if they are not provided. To show how the documents support the different interpretations, enter the corresponding document number into the boxes near the interpretation. Write your conclusion response in the space provided. Interpretation 1

Title

Interpretation 2

1

Activity Element

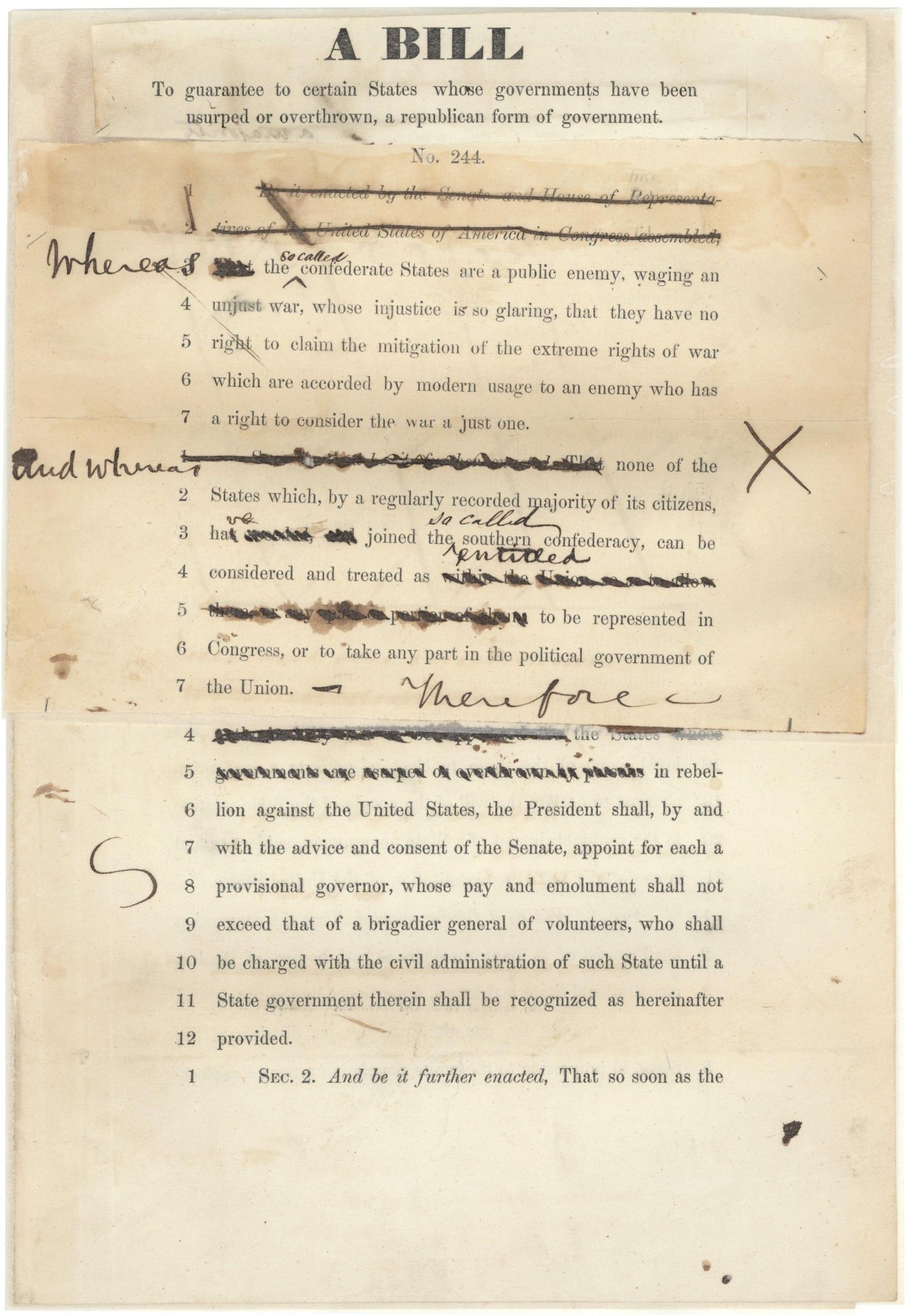

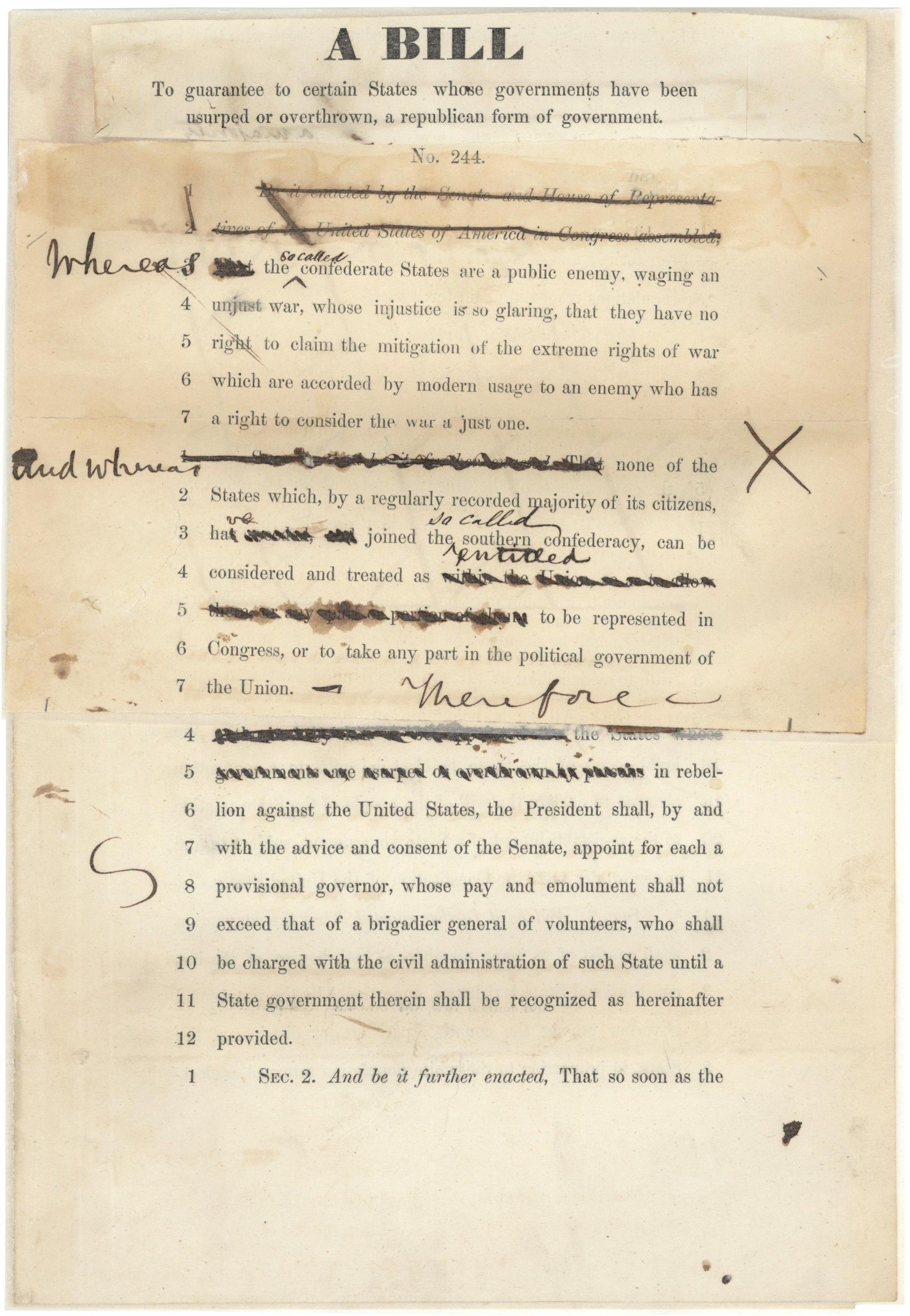

Wade-Davis Bill as Amended

Page 1

2

Activity Element

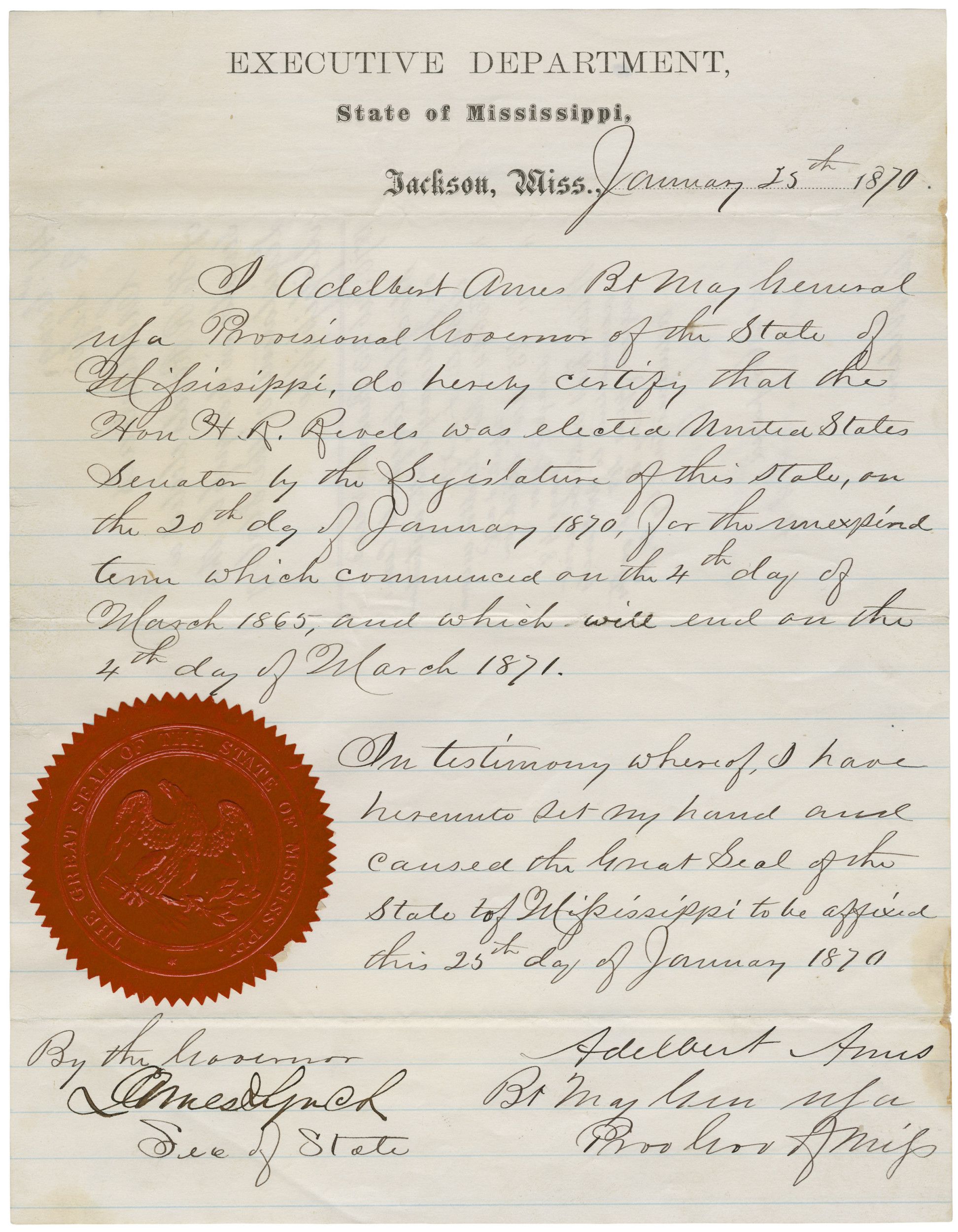

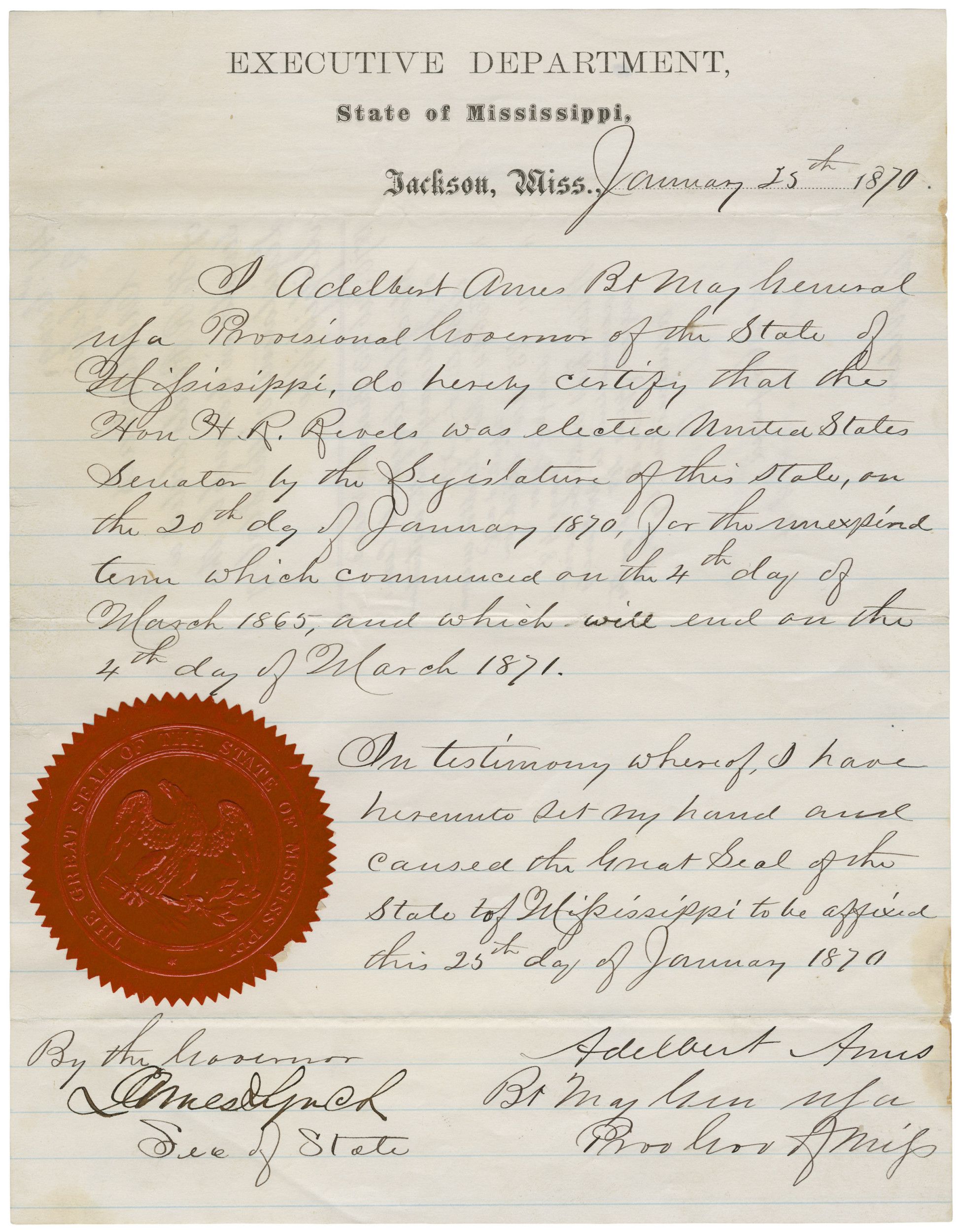

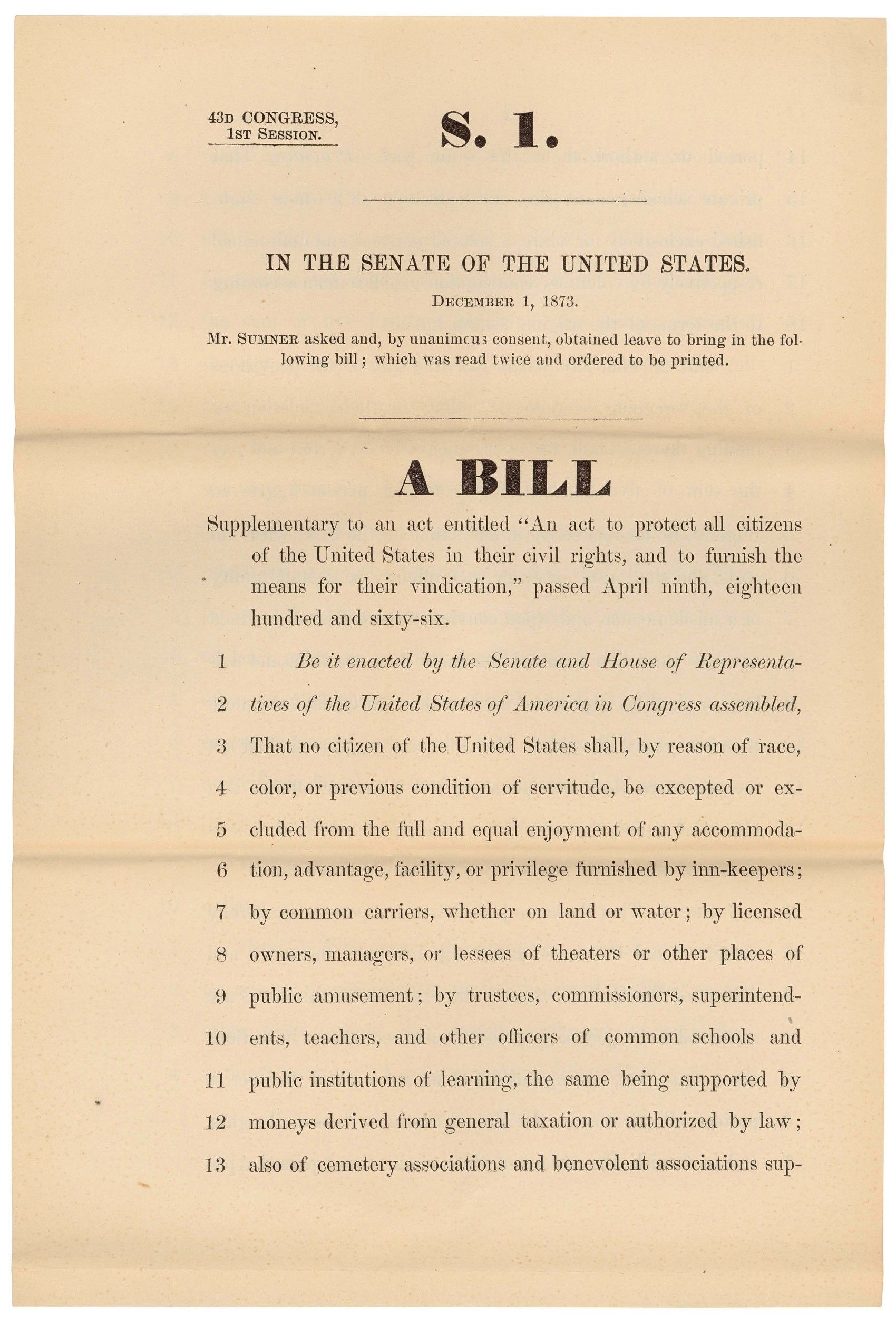

Credentials of Hiram Rhodes Revels

Page 1

3

Activity Element

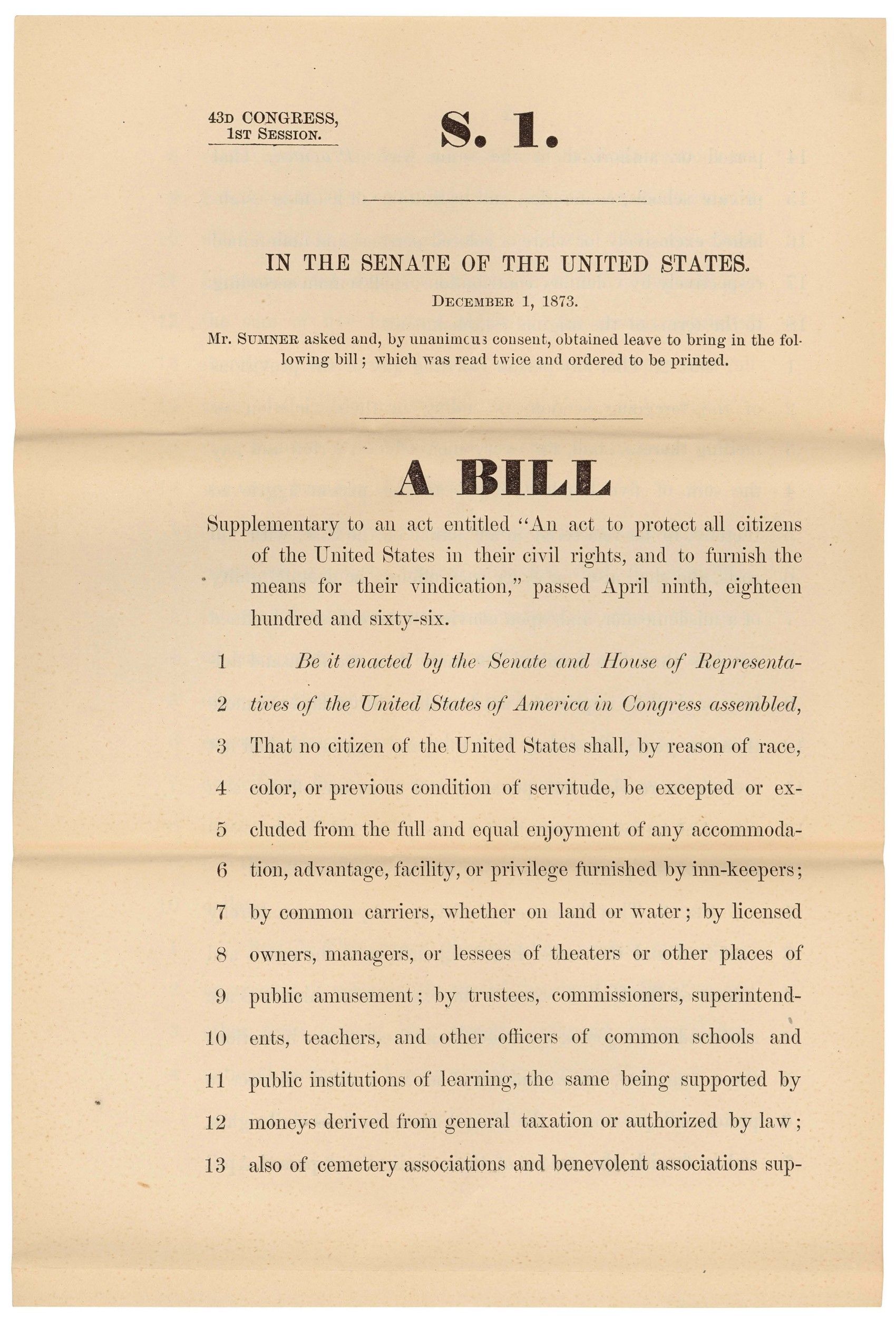

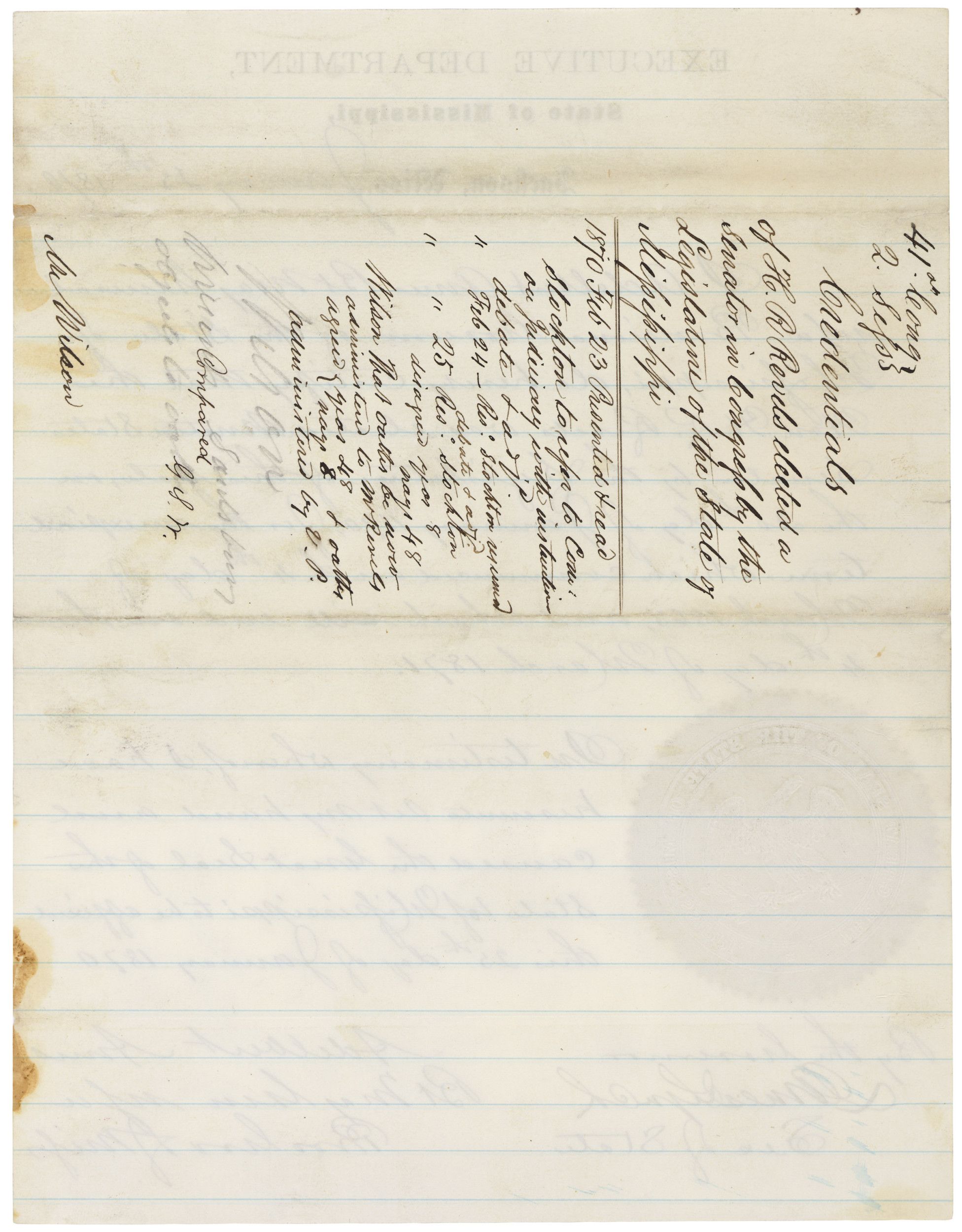

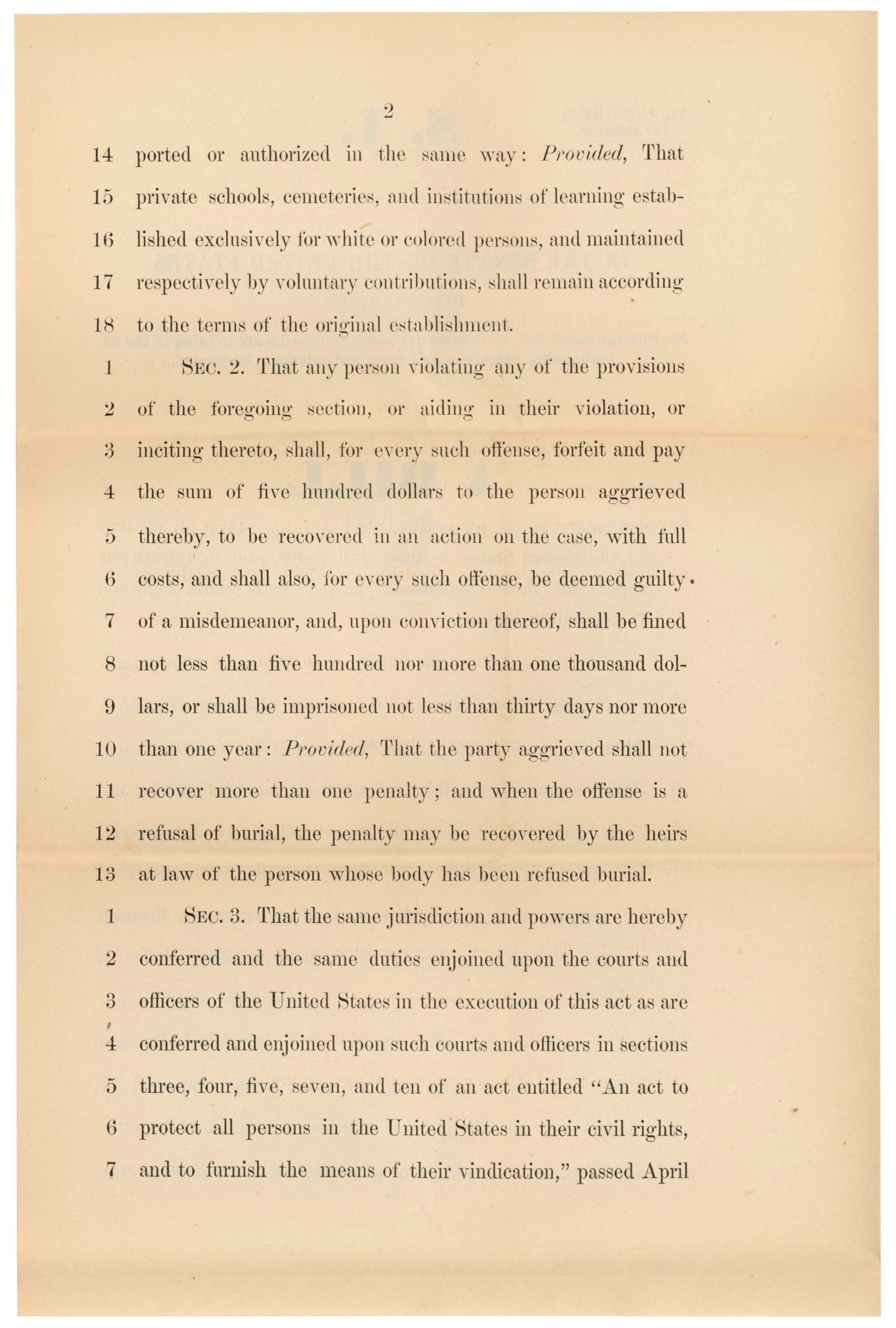

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 1

4

Activity Element

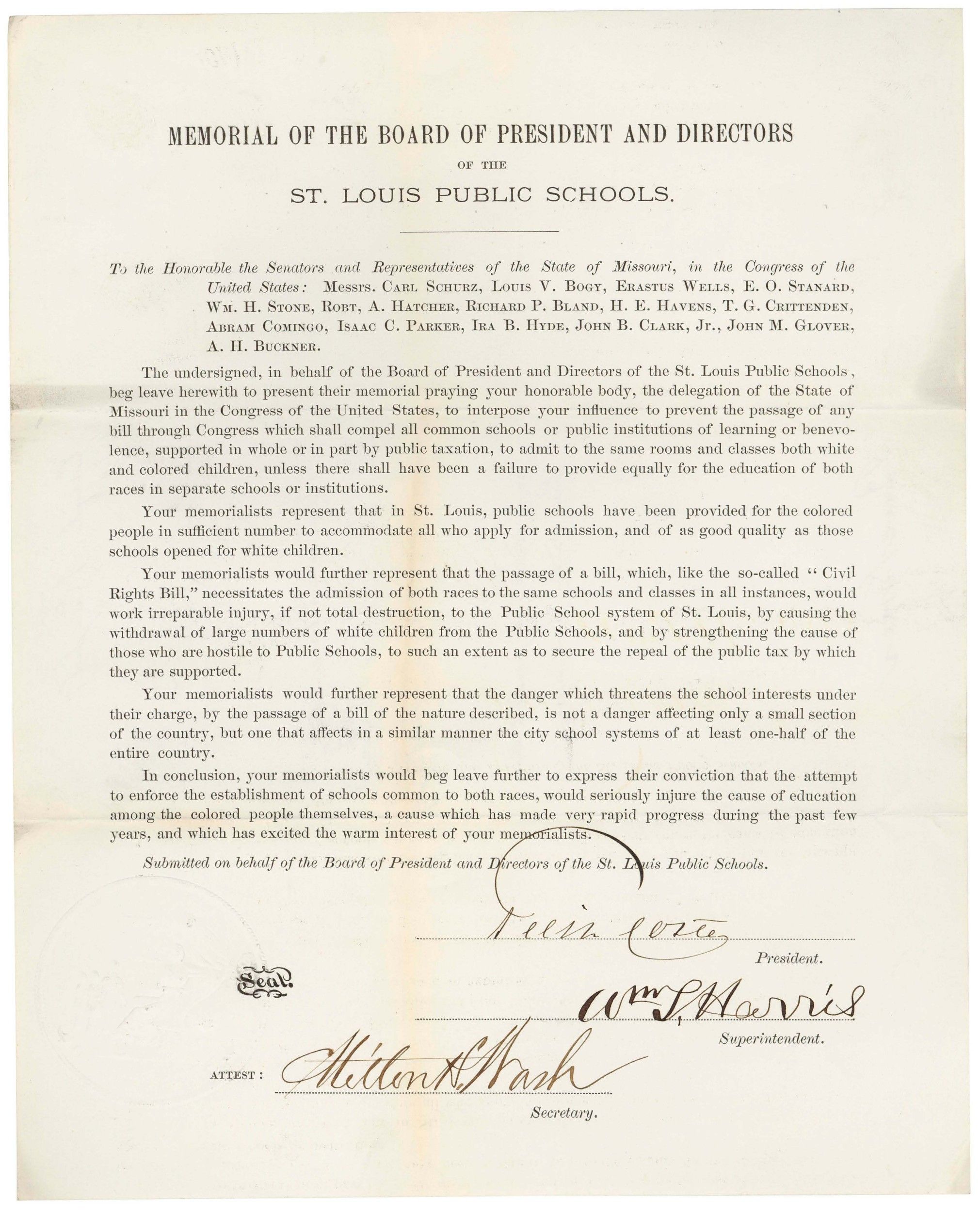

Memorial of the Board of the President and Directors of the St. Louis Public Schools Against Racial Integration of Public Schools

Page 1

5

Activity Element

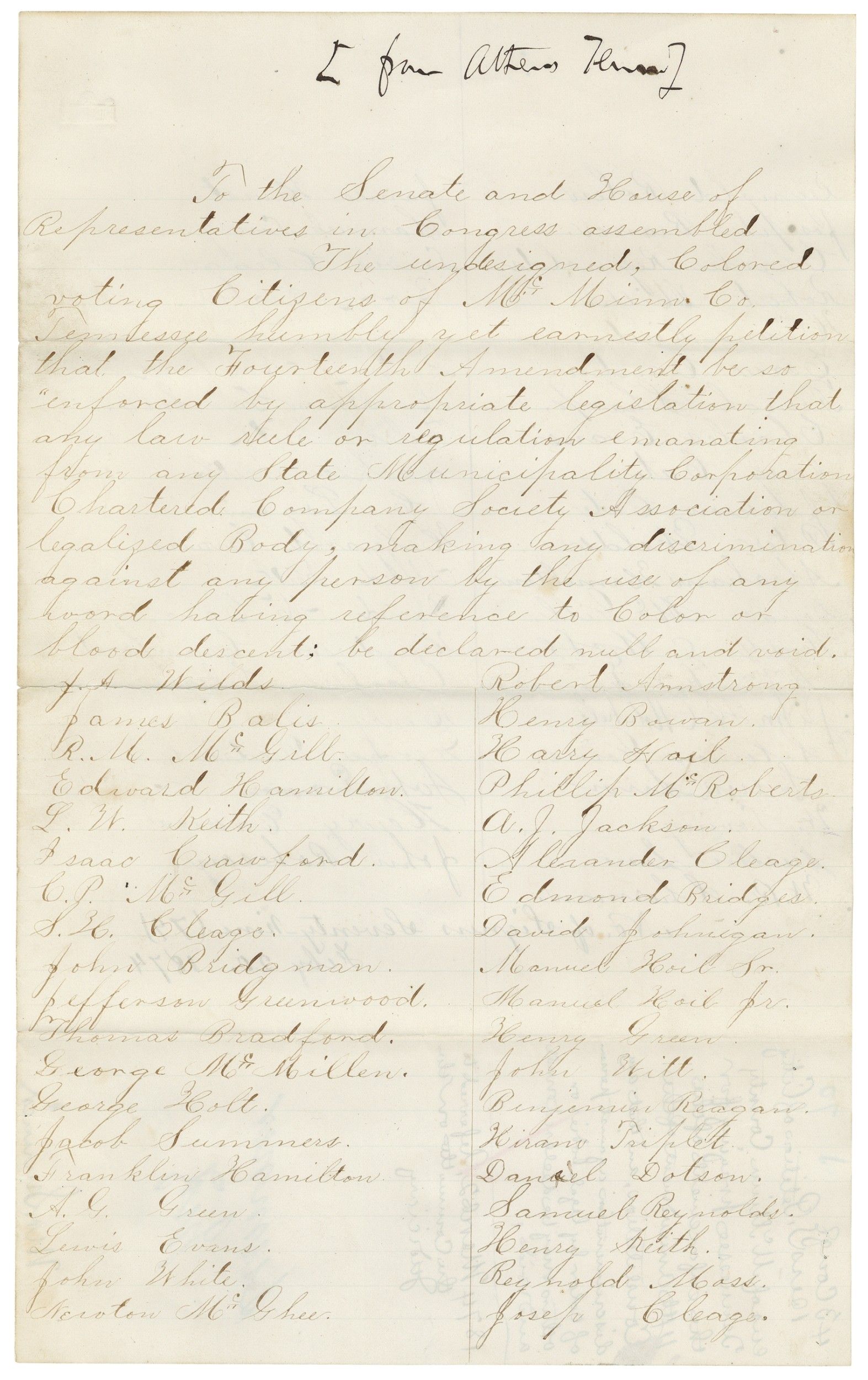

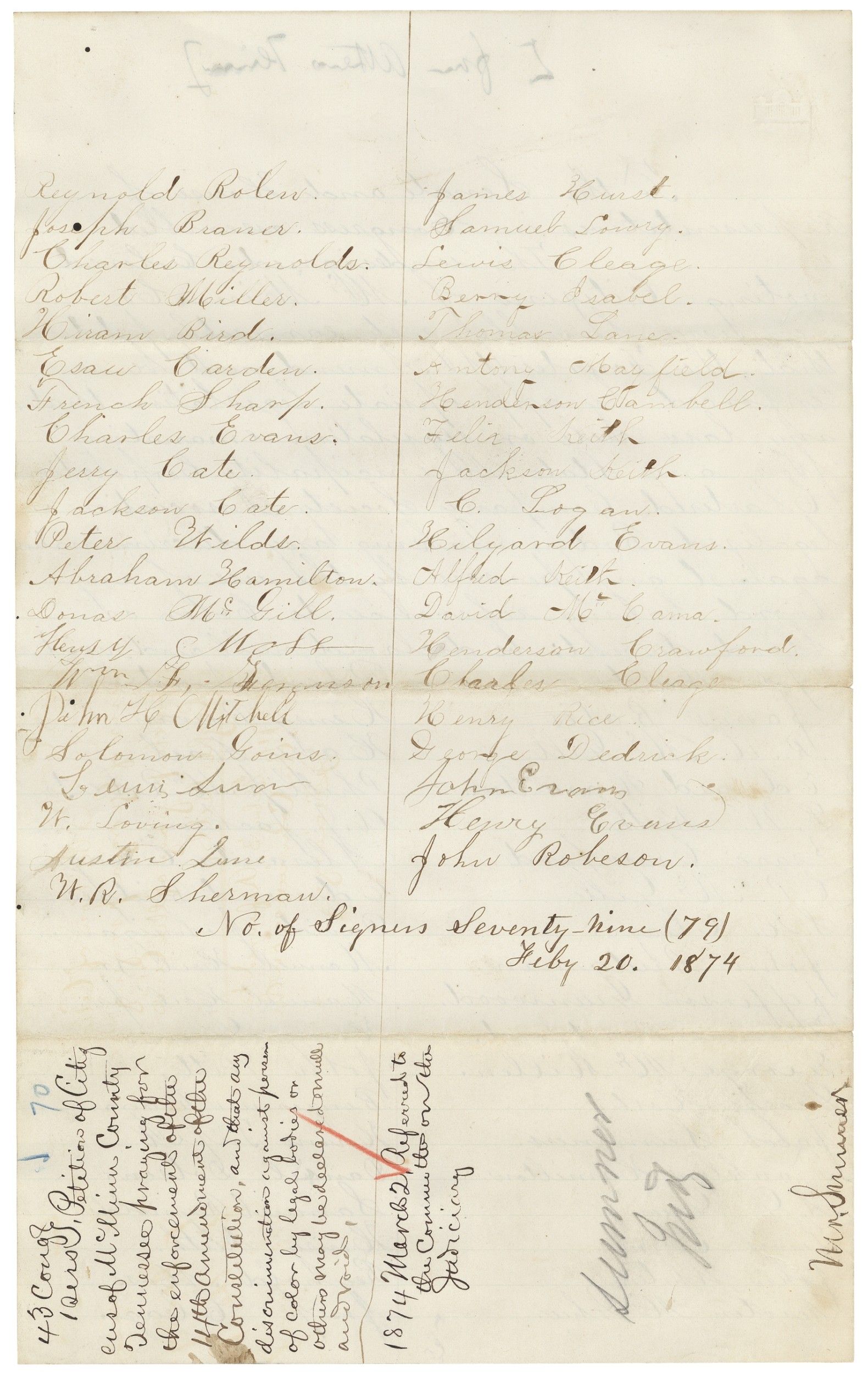

Petition of Colored Citizens of McMinn County, Tennessee, Praying for Protection of Civil Rights under Fourteenth Amendment

Page 1

6

Activity Element

Memorial of the Colored People of Georgia in Favor of the Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 1

7

Activity Element

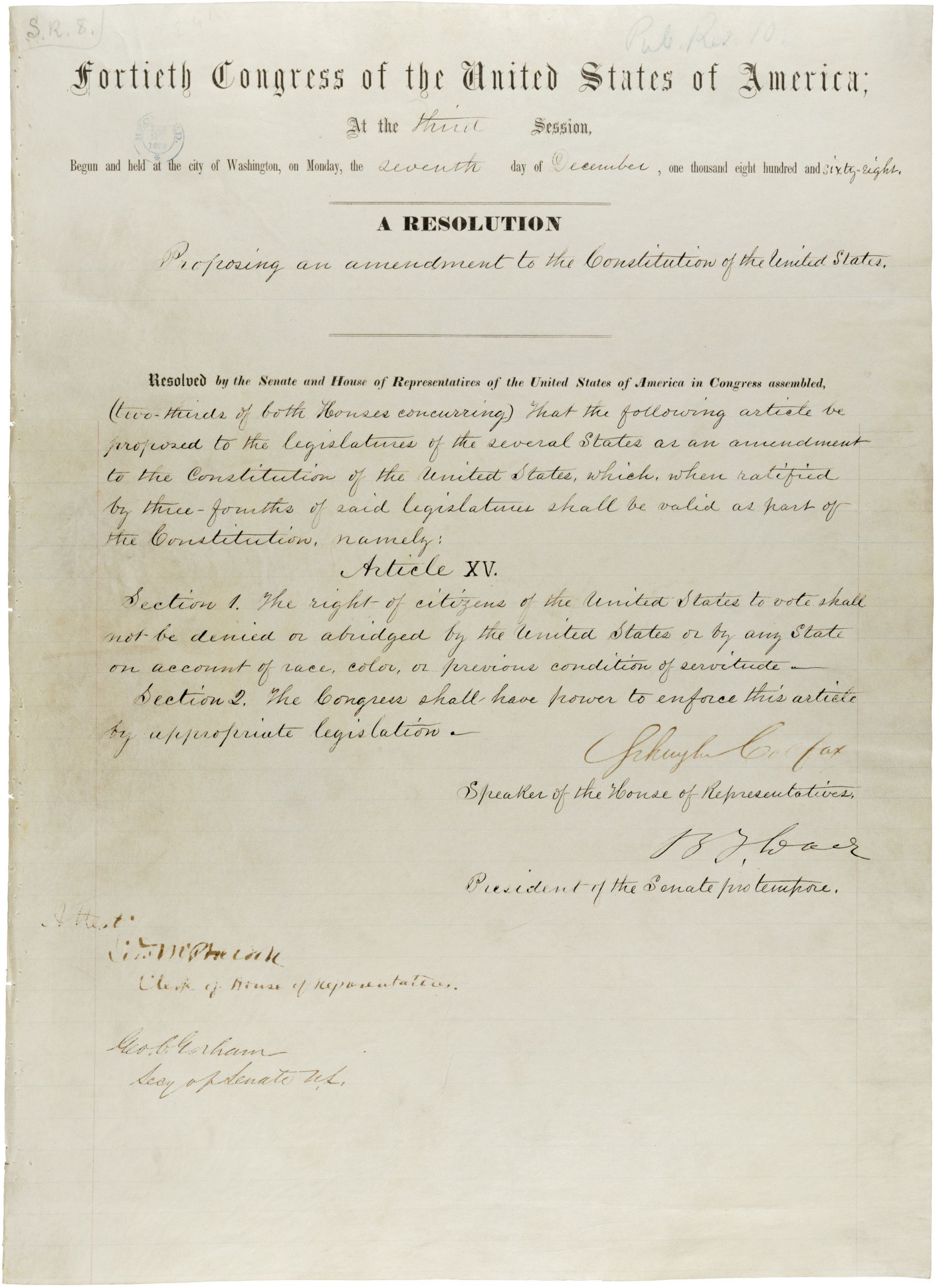

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1

Conclusion

To What Extent was Reconstruction a Revolution? (Part 1)

Weighing the Evidence

- What evidence did you see in the documents which illustrated significant change occurring?

- What evidence depicted things staying the same?

- Taking into account information from the documents as well as the introductory discussion on revolutions, answer the guiding question: To what extent was Reconstruction a revolution? Before sending your email to complete Part 1, open Part 2 of this activity.

Your Response

Document

Wade-Davis Bill, as Amended

5/4/1864

In late 1863, President Abraham Lincoln and Congress began to consider the question of how the Union would be reunited if the North won the Civil War. In December, President Lincoln proposed a reconstruction program that would allow Confederate states to establish new state governments after 10 percent of their male population took loyalty oaths and the states recognized the permanent freedom of formerly enslaved people.

Several congressional Republicans thought Lincoln’s 10 percent plan was too lenient. Senator Benjamin F. Wade, of Ohio, and Representative Henry Winter Davis, of Maryland, proposed a more stringent plan in February 1864.

The Wade-Davis Reconstruction Bill would also have abolished slavery, but it required that 50 percent of a state's White males take a loyalty oath to the United States (and swear they had never assisted the Confederacy) to be readmitted to the Union. Only after taking this "Ironclad Oath" would they be able to participate in conventions to write new state constitutions.

Congress passed the Wade-Davis Bill, but President Lincoln chose not to sign it, killing the bill with a pocket veto. Lincoln continued to advocate tolerance and speed in plans for the reconstruction of the Union in opposition to Congress.

After Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, however, Congress had the upper hand in shaping federal policy toward the defeated South and imposed the harsher reconstruction requirements first advocated in the Wade-Davis Bill. Some of the policies included in this bill were implemented in a series of four Reconstruction Acts (1867-1868), which were passed into law after Congress overrode the vetoes of President Andrew Johnson.

Several congressional Republicans thought Lincoln’s 10 percent plan was too lenient. Senator Benjamin F. Wade, of Ohio, and Representative Henry Winter Davis, of Maryland, proposed a more stringent plan in February 1864.

The Wade-Davis Reconstruction Bill would also have abolished slavery, but it required that 50 percent of a state's White males take a loyalty oath to the United States (and swear they had never assisted the Confederacy) to be readmitted to the Union. Only after taking this "Ironclad Oath" would they be able to participate in conventions to write new state constitutions.

Congress passed the Wade-Davis Bill, but President Lincoln chose not to sign it, killing the bill with a pocket veto. Lincoln continued to advocate tolerance and speed in plans for the reconstruction of the Union in opposition to Congress.

After Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, however, Congress had the upper hand in shaping federal policy toward the defeated South and imposed the harsher reconstruction requirements first advocated in the Wade-Davis Bill. Some of the policies included in this bill were implemented in a series of four Reconstruction Acts (1867-1868), which were passed into law after Congress overrode the vetoes of President Andrew Johnson.

Transcript

A Bill to guarantee to certain States whose Governments have been usurped or overthrown a Republican Form of Government.Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That in the states declared in rebellion against the United States, the President shall, by and with the advice and con- sent of the Senate, appoint for each a provisiona1 governor, whose pay and emoluments shall not exceed that of a brigadier-general of volunteers, who shall be charged with the civil administration of such state until a state government therein shall be recognized as hereinafter provided.

SEC. 2. And be it further enacted, That so soon as the ...

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives.

National Archives Identifier: 5049648

Full Citation: Wade-Davis Bill, as Amended; 5/4/1864; Bills and Resolutions Originating in the House, 1789 - 1974; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/wade-davis-bill, April 25, 2024]Wade-Davis Bill, as Amended

Page 1

Document

Credentials of Hiram Rhodes Revels

1/25/1870

Dated January 25, 1870, these are the credentials for Senator Hiram Rhodes Revels of Mississippi, the first African American to serve in the Senate.

Transcript

[typed]EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT

State of Mississippi

Jackson, Miss. [hand written] January 25th, 1870.

[handwritten]

I Adelbert Ames Br Maj General USA Provisional Governor of the State of Mississippi, do hereby certify that the Hon H.R. Revels was elected United States Senator by the Legislature of this state, on the 20th day of January 1870, for the unexpired term which commenced on the 4th day of March 1865, and which will end on the 4th day of March 1871.

[seal of Mississippi affixed to page]

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and caused the Great Seal of the State of Mississippi to be affixed this 25th day of January 1870.

[left]

By the Governor

James Lynch

Sec of State

[right]

Adelbert Ames

Br. Maj. Gen. USA

Prov. Gov of Miss

41st Cong

2. Sesss

Credentials

Of H.R Revels elected a Senator in Congress by the Legislature of the State of Mississippi

[horizontal line]

1870 Feb 23 Presented & read

Stockton to refer to Com on Judiciary with instruction debate & advis

[1870] Feb 24 - Reso: Stockton rescinded debate & advis

[1870] Feb 25-Reso: Stockton disagreed Yeas 8 Nays 48

Wilson that oaths now be administered to Mr Revels agreed yeas 48 nays 8 & oaths administered by V. P.

Compared

G.S.W.

Mr. Wilson

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 595424

Full Citation: Credentials of Hiram Rhodes Revels; 1/25/1870; Credentials, 1789 - 1998; Records of the U.S. Senate, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/credentials-hiram-rhodes-revels, April 25, 2024]Credentials of Hiram Rhodes Revels

Page 1

Credentials of Hiram Rhodes Revels

Page 2

Document

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

12/1/1873

There was a great divide over how far the Government should go to enforce the rights established by the 14th and 15th Amendments. The Civil Right Act of 1875, first proposed by Senator Charles Sumner in 1870, was an attempt to codify those rights.

Senator Sumner was the chief Radical Republican leader during Reconstruction and a vocal proponent of civil rights for freedmen. He introduced the version shown here to the Senate in 1873. It proposed to prohibit racial discrimination in public accommodations, such as hotels, theaters, transportation, and schools. He was so determined to see it pass that on his deathbed in 1874 he begged Frederick Douglass not to let it fail.

The bill that passed after much debate and revision in 1875 stated that all American citizens “shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement.” Prior to passage, Congress removed the clause which prohibited discrimination in public schools.

Senator Sumner was the chief Radical Republican leader during Reconstruction and a vocal proponent of civil rights for freedmen. He introduced the version shown here to the Senate in 1873. It proposed to prohibit racial discrimination in public accommodations, such as hotels, theaters, transportation, and schools. He was so determined to see it pass that on his deathbed in 1874 he begged Frederick Douglass not to let it fail.

The bill that passed after much debate and revision in 1875 stated that all American citizens “shall be entitled to the full and equal enjoyment of the accommodations, advantages, facilities, and privileges of inns, public conveyances on land or water, theaters, and other places of public amusement.” Prior to passage, Congress removed the clause which prohibited discrimination in public schools.

Sumner, who died in 1874, did not live to celebrate the bill’s passage. Nor did he see its ultimate failure when, in 1883, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives.

National Archives Identifier: 1986640

Full Citation: Sumner Civil Rights Bill; 12/1/1873; (HR43A-C1); Bills and Resolutions Originating in the Senate and Considered in the House, 1789 - 2003; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/sumner-civil-rights-bill, April 25, 2024]Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 1

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 2

Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 3

Document

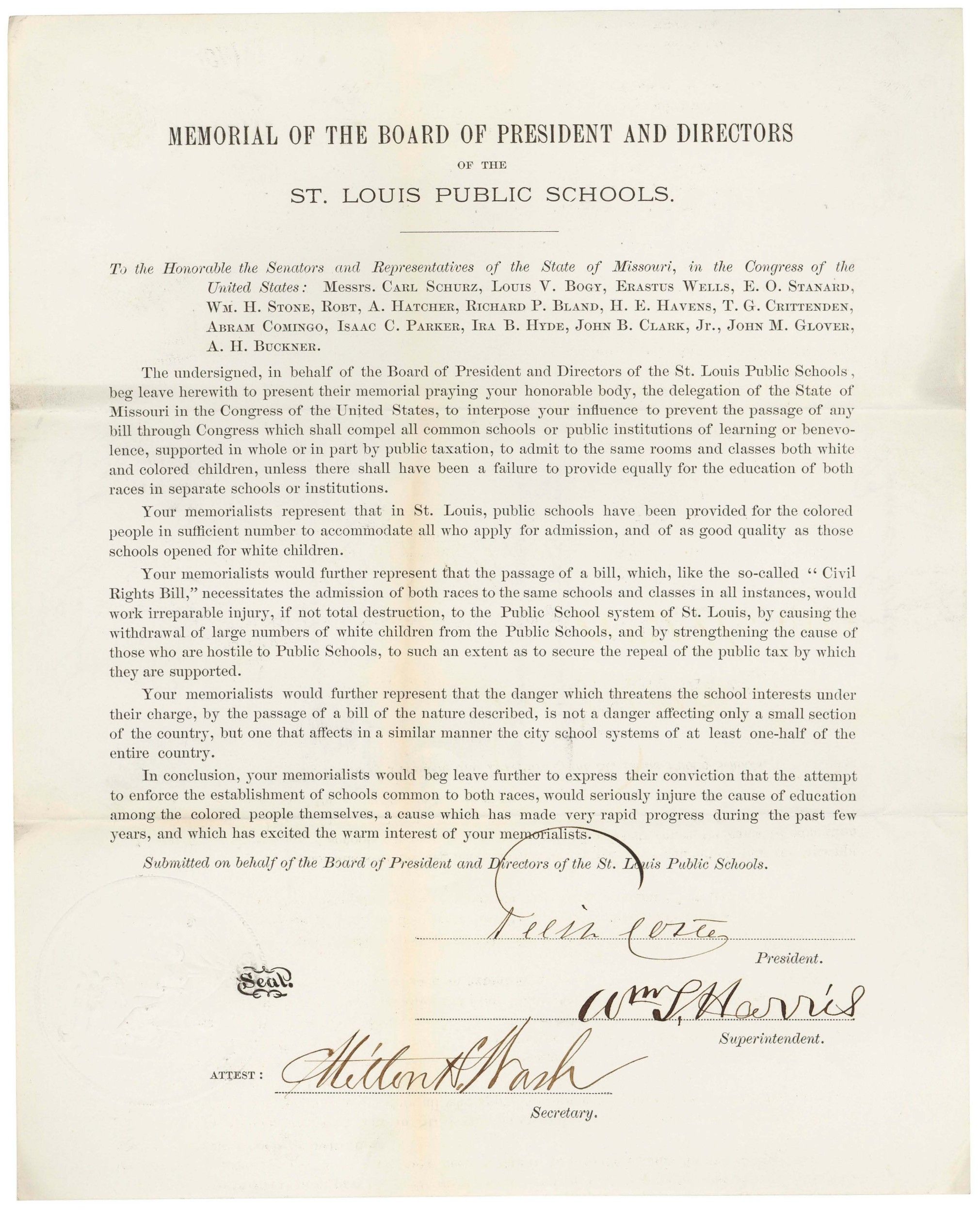

Memorial of the Board of the President and Directors of the St. Louis Public Schools Against Racial Integration of Public Schools

6/16/1874

This document refers to a clause in the Sumner Civil Rights bill (S. 1, 43rd Congress) which would have required the racial integration of public schools. This clause was removed before the Sumner Civil Rights Act of 1875 (18 Stat 335) was passed into law.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives.

National Archives Identifier: 1991060

Full Citation: Memorial of the Board of the President and Directors of the St. Louis Public Schools Against Racial Integration of Public Schools; 6/16/1874; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, . [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/memorial-st-louis-schools, April 25, 2024]Memorial of the Board of the President and Directors of the St. Louis Public Schools Against Racial Integration of Public Schools

Page 1

Document

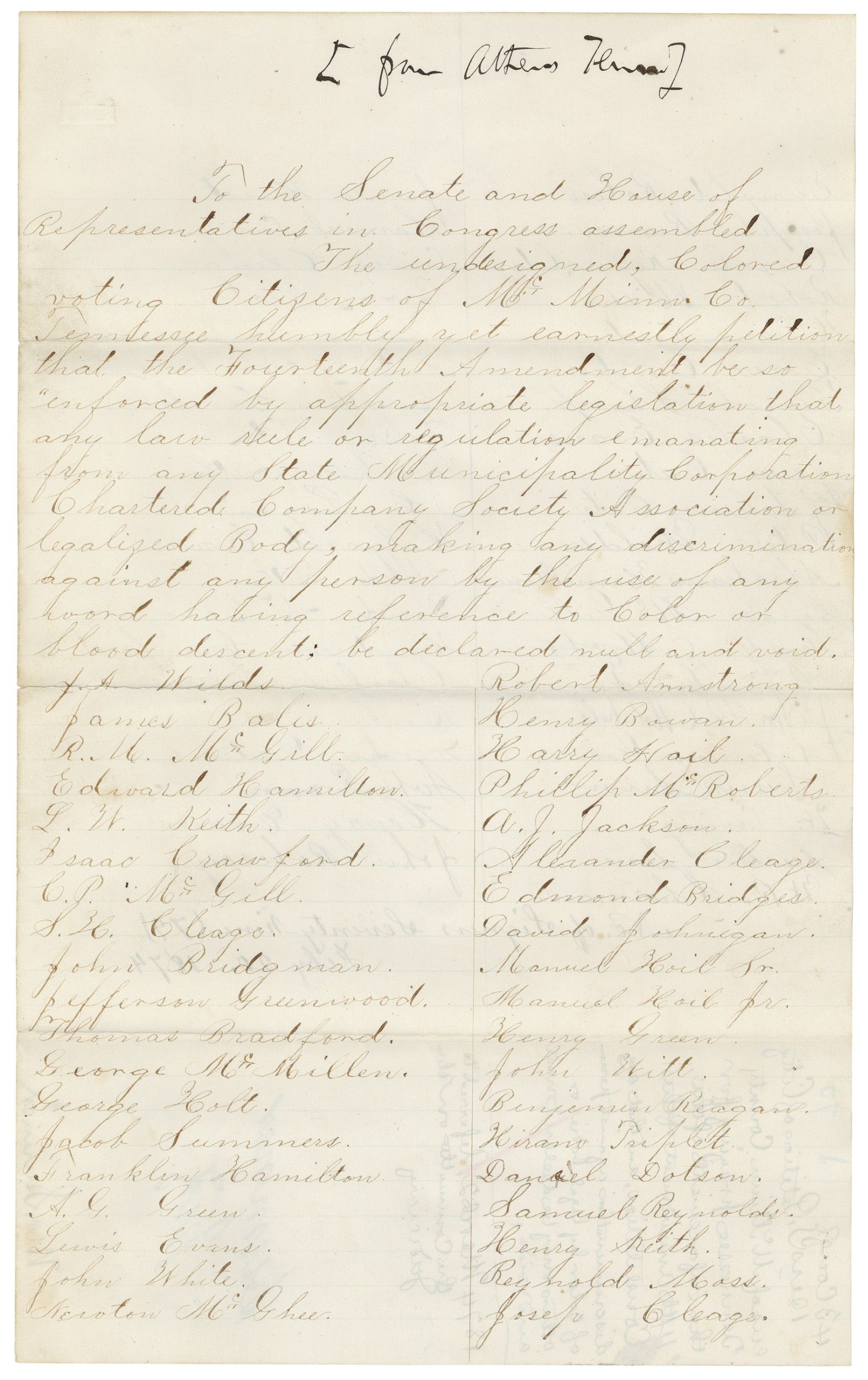

Petition of Colored Citizens of McMinn County, Tennessee, Praying for Protection of Civil Rights under Fourteenth Amendment

3/2/1874

A major provision of the 14th Amendment, ratified on July 28, 1868, was to grant citizenship to “All persons born or naturalized in the United States.” Thus it spelled out the status of newly freed slaves—they were to be equal citizens under the law. It also assured all citizens of “due process of law” and “equal protection of the laws.”

In 1874, seventy-nine "Colored Voting Citizens of McMinn [County], Tennessee" sent this memorial to Congress asking for protection of their civil rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. They asked for the amendment to be so “enforced by appropriate legislation that any law rule or regulation emanating from any State Municipality Corporation or legalized Body, making any discrimination against any person by the use of any word having reference to Color or blood descent; be declared null and void."

In 1883, however, the Supreme Court decided that the 14th Amendment only restricted state action and didn't nullify laws making reference to color.

In 1874, seventy-nine "Colored Voting Citizens of McMinn [County], Tennessee" sent this memorial to Congress asking for protection of their civil rights under the Fourteenth Amendment. They asked for the amendment to be so “enforced by appropriate legislation that any law rule or regulation emanating from any State Municipality Corporation or legalized Body, making any discrimination against any person by the use of any word having reference to Color or blood descent; be declared null and void."

In 1883, however, the Supreme Court decided that the 14th Amendment only restricted state action and didn't nullify laws making reference to color.

Transcript

[from Athens Tenn]To the Senate and House of Representatives in Congress assembled.

The undersigned, Colored voting Citizens of McMinn Co. Tennessee humbly yet earnestly petition that the Fourteenth Amendment be so "enforced by appropriate legislation that any law, rule, or regulation emanating from any State Municipality Corporation Chartered Company Society Association or legalized Body, making any discrimination against any person by the use of any word having reference Color or blood descent; be declared null and void.

{signatures}

No. of Signers Seventy-Nine (790

Feby 20. 1874

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 5637786

Full Citation: Petition of Colored Citizens of McMinn County, Tennessee, Praying for Protection of Civil Rights under Fourteenth Amendment; 3/2/1874; Petition and Memorials, Resolutions of State Legislatures, and Related Documents which were Referred to the Committee on the Judiciary during the 43rd Congress; (Sen 43A-H11.1); Committee Papers, 1816 - 2011; Records of the U.S. Senate, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/citizens-mcminn-county, April 25, 2024]Petition of Colored Citizens of McMinn County, Tennessee, Praying for Protection of Civil Rights under Fourteenth Amendment

Page 1

Petition of Colored Citizens of McMinn County, Tennessee, Praying for Protection of Civil Rights under Fourteenth Amendment

Page 2

Document

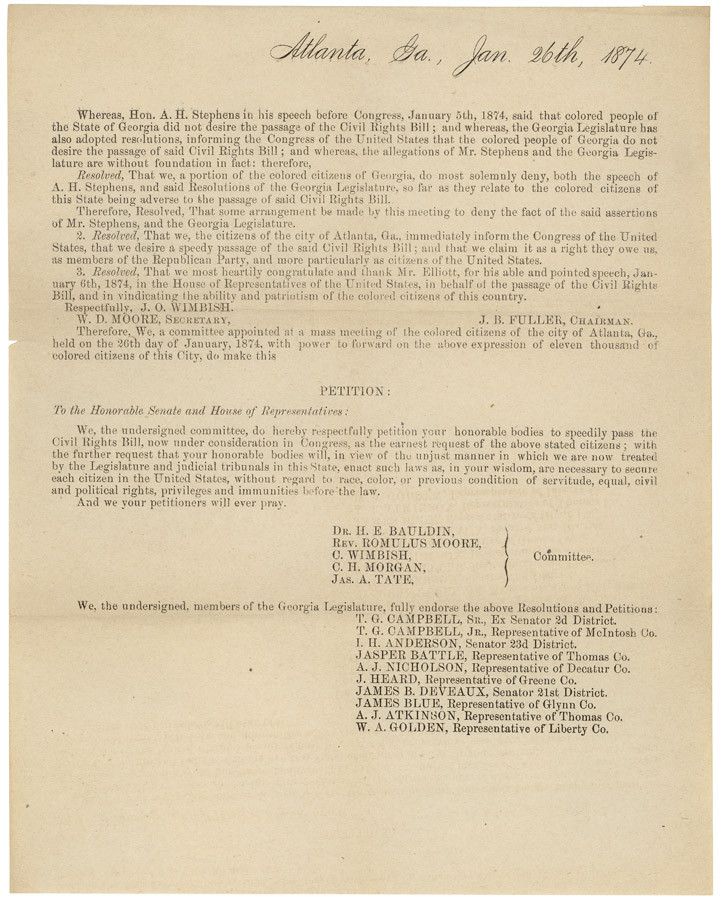

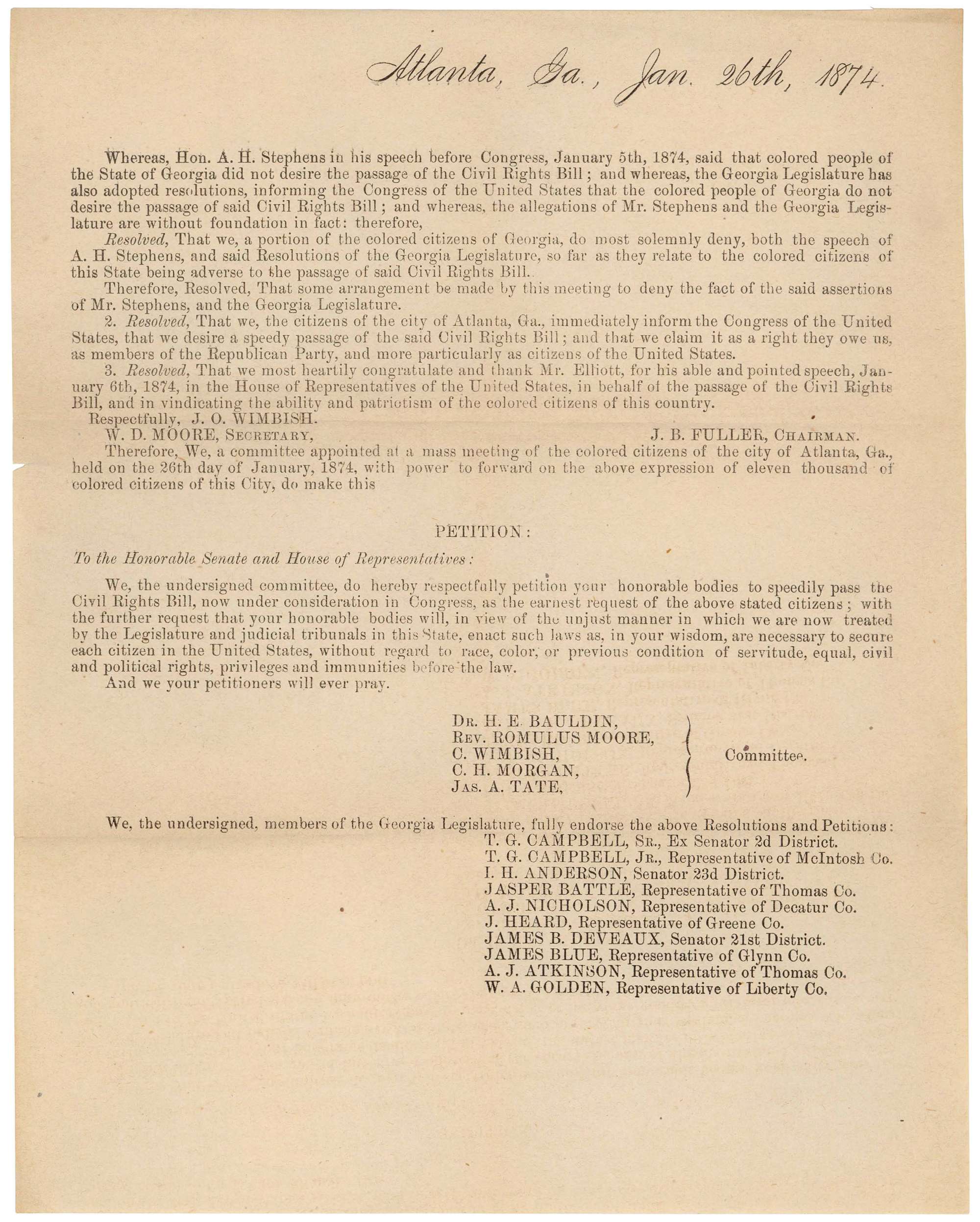

Memorial of the Colored People of Georgia in Favor of the Sumner Civil Rights Bill

1/26/1874

This petition was sent to Congress by a committee "appointed at a mass meeting of the colored citizens of the city of Atlanta, Ga....with power to forward on the [feelings] of eleven thousand of colored citizens of [Atlanta]." They dispute the Georgia Legislature's previous resolutions informing the U.S. Congress "that the colored people of Georgia do not desire the passage of [the] Civil Rights Bill," and instead ask Congress to "speedily pass" it.

Transcript

Atlanta, Ga., Jan. 26th, 1874.Whereas, Hon. A. H. Stephens in his speech before Congress, January 5th, 1874, said that colored people of the State of Georgia did not desire the passage of the Civil Rights Bill; and whereas, the Georgia Legislature has also adopted resolutions, informing the Congress of the United States that the colored people of Georgia do not desire the passage of said Civil Rights Bill; and whereas, the allegations of Mr. Stephens and the Georgia Legislature are without foundation in fact: therefore,

Resolved, That we, a portion of the colored citizens of Georgia, do most solemnly deny, both the speech of A. H. Stephens, and said Resolutions of the Georgia Legislature, so far as they relate to the colored citizens of this State being adverse to the passage of said Civil Rights Bill.

Therefore, Resolved, That some arrangement be made by this meeting to deny the fact of the said assertions of Mr. Stephens, and the Georgia Legislature.

2. Resolved, That we, the citizens of the city of Atlanta, Ga., immediately inform the Congress of the United States, that we desire a speedy passage of the said Civil Rights Bill; and that we claim it as a right they owe us, as members of the Republican Party, and more particularly as citizens of the United States.

3. Resolved, That we most heartedly congratulate and thank Mr. Elliott, for his able and pointed speech, January 6th, 1874, in the House of Representatives of the United States, in behalf of the passage of the Civil Rights Bill, and in vindicating the ability and patriotism of the colored citizens of this country.

Respectfully, J. O. WIMBISH

W. D. MOORE, SECRETARY,

J. B. FULLER, CHAIRMAN.

Therefore, We, a committee appointed at a mass meeting of the colored citizens of the city of Atlanta, Ga., held on the 26th day of January, 1874, with power to forward on the above expression of eleven thousand of colored citizens of this City, do make this

PETITION:

To the Honorable Senate and House of Representatives:

We, the undersigned committee, do hereby respectfully petition your honorable bodies to speedily pass the Civil Rights Bill, now under consideration in Congress, as the earnest request of the above stated citizens; wit hthe further request that your honorable bodies will, in view of the unjust manner in which we are now treated by the Legislature and the judicial tribunals in this State, enact such laws as, in your wisdom, are necessary to secure each citizen in the United States, without regard to race, color, or previous condition of servitude, equal civil and political rights, privileges and immunities before the law.

And we your petitioners will ever pray.

Dr. H. E. BAULDIN

REV. ROMULUS MOORE

C. WIMBISH

C. H. MORGAN

JAS. A. TATE.

[label outside bracket] Committee.

We, the undersigned, members of the Georgia Legislature, fully endorse the above Resolutions and Petitions:

T. G. CAMPBELL, SR. Ex. Senator 2d District.

T. G. CAMPBELL, JR., Representative of McIntosh Co.

I. H. ANDERSON, Senator 23d District.

JASPER BATTLE, Representative of Thomas Co.

A. J. NICHOLSON, Representative of Decatur Co.

J. HEARD, Representative of Greene Co.

JAMES B DEVEAUX, Senator 21st District.

JAMES BLUE, Representative of Glynn Co.

A. J. ATKINSON, Representative of Thomas Co.

W. A. GOLDEN, Representative of Liberty Co.

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. House of Representatives.

National Archives Identifier: 1991057

Full Citation: Memorial of the Colored People of Georgia in Favor of the Sumner Civil Rights Bill; 1/26/1874; (HR 43A-H8.3); Petitions and Memorials, 1813 - 1968; Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/memorial-sumner-civil-rights-bill, April 25, 2024]Memorial of the Colored People of Georgia in Favor of the Sumner Civil Rights Bill

Page 1

Document

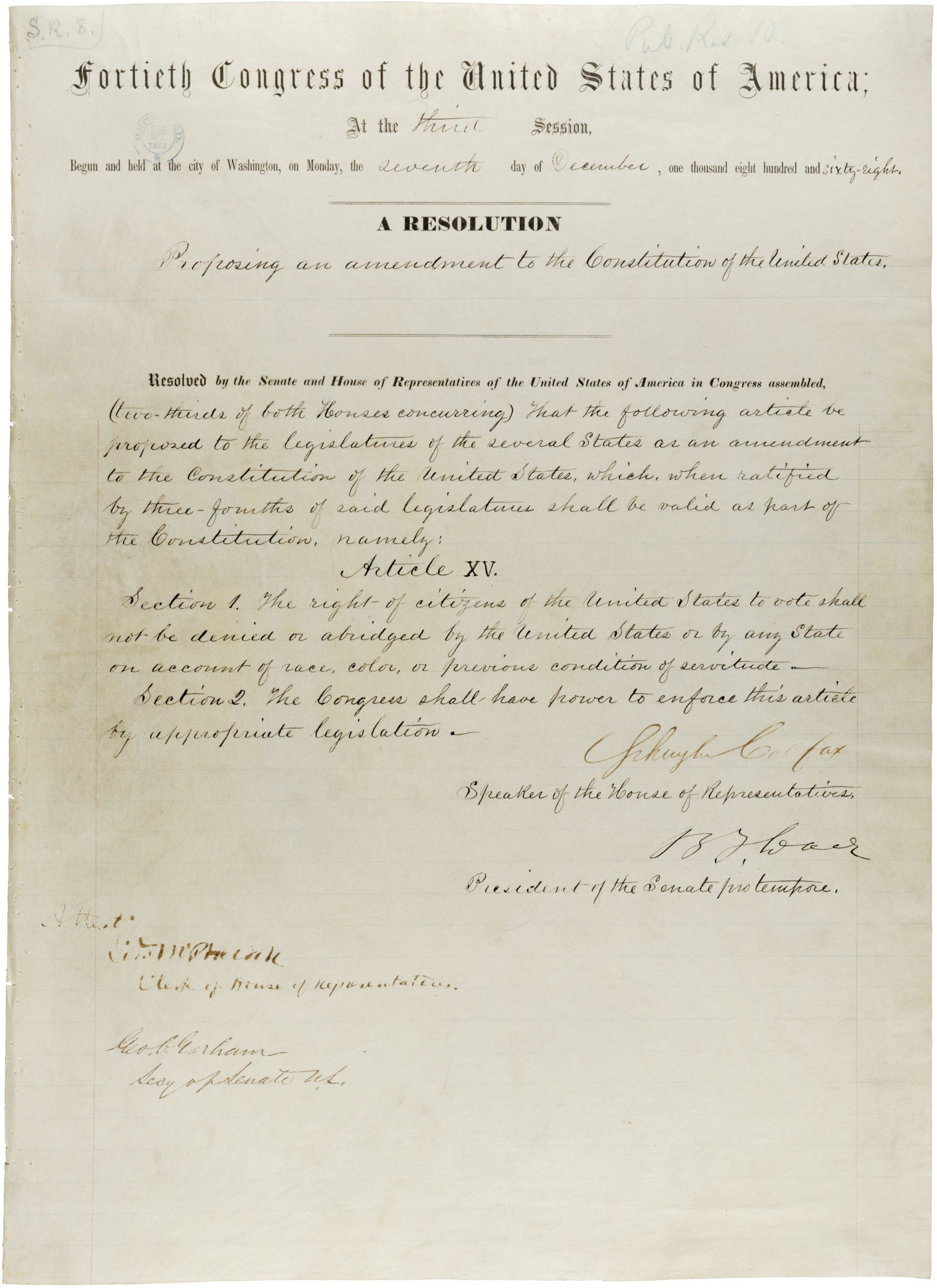

Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

2/26/1869

Passed by Congress on February 26, 1869, and ratified February 3, 1870, the 15th amendment granted African-American men the right to vote: the right of male U.S. citizens to vote shall not be denied or abridged “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This document is the joint resolution – a formal opinion adopted by both houses of the legislative branch – proposing the amendment. A constitutional amendment must be passed as a joint resolution before it is sent to the states for ratification.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the 15th amendment appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the 13th amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the 14th amendment, Black males were given the vote by the 15th amendment.

African Americans voted and held office in many Southern states through the 1880s, but in the early 1890s, steps were taken to ensure subsequent “white supremacy.” The 15th Amendment had been carefully worded to maximize its chances of ratification. It didn't go so far as to grant the right to vote to all citizens regardless of race —instead, it barred states from denying suffrage based on race, opening a loophole for literacy, land ownership, or other requirements. It was a loophole that Southern states quickly exploited to effectively ban Black people from the polls.

Literacy tests for the vote, “grandfather clauses” excluding those whose ancestors had not voted in the 1860s, and other devices to disenfranchise African Americans were written into the laws of former Confederate states.

Social and economic segregation were added to Black America’s loss of political power. In 1896, the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson legalized “separate but equal” facilities for the races. For more than 50 years, the overwhelming majority of African American citizens were reduced to second-class citizenship under the “Jim Crow” segregation system.

During that time, African Americans sought to secure their rights and improve their position through organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) and the National Urban League, and through the individual efforts of reformers like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and A. Philip Randolph.

The most direct attack on the problem of African-American disfranchisement came in 1965. Prompted by reports of continuing discriminatory voting practices in many Southern states, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Congress to pass legislation “which will make it impossible to thwart the 15th amendment.” He reminded Congress that “we cannot have government for all the people until we first make certain it is government of and by all the people.”

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, extended in 1970, 1975, and 1982, abolished all remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorized federal supervision of voter registration where necessary. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the act involving federal oversight of voting rules in nine states.

To former abolitionists and to the Radical Republicans in Congress who fashioned Reconstruction after the Civil War, the 15th amendment appeared to signify the fulfillment of all promises to African Americans. Set free by the 13th amendment, with citizenship guaranteed by the 14th amendment, Black males were given the vote by the 15th amendment.

African Americans voted and held office in many Southern states through the 1880s, but in the early 1890s, steps were taken to ensure subsequent “white supremacy.” The 15th Amendment had been carefully worded to maximize its chances of ratification. It didn't go so far as to grant the right to vote to all citizens regardless of race —instead, it barred states from denying suffrage based on race, opening a loophole for literacy, land ownership, or other requirements. It was a loophole that Southern states quickly exploited to effectively ban Black people from the polls.

Literacy tests for the vote, “grandfather clauses” excluding those whose ancestors had not voted in the 1860s, and other devices to disenfranchise African Americans were written into the laws of former Confederate states.

Social and economic segregation were added to Black America’s loss of political power. In 1896, the Supreme Court decision Plessy v. Ferguson legalized “separate but equal” facilities for the races. For more than 50 years, the overwhelming majority of African American citizens were reduced to second-class citizenship under the “Jim Crow” segregation system.

During that time, African Americans sought to secure their rights and improve their position through organizations such as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.) and the National Urban League, and through the individual efforts of reformers like Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. DuBois, and A. Philip Randolph.

The most direct attack on the problem of African-American disfranchisement came in 1965. Prompted by reports of continuing discriminatory voting practices in many Southern states, President Lyndon B. Johnson urged Congress to pass legislation “which will make it impossible to thwart the 15th amendment.” He reminded Congress that “we cannot have government for all the people until we first make certain it is government of and by all the people.”

The Voting Rights Act of 1965, extended in 1970, 1975, and 1982, abolished all remaining deterrents to exercising the right to vote and authorized federal supervision of voter registration where necessary. In 2013, the Supreme Court struck down a key provision of the act involving federal oversight of voting rules in nine states.

Transcript

Fortieth Congress of the United States of America;At the third Session, Begun and held at the city of Washington, on Monday, the seventh day of December, one thousand eight hundred and sixty-eight.

A Resolution

Proposing an amendment to the Constitution of the United States.

Resolved by the Senate and House of Respresentatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, (two-thirds of both Houses concurring) that the following article be proposed to the legislature of the several States as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States which, when ratified by three-fourths of said legislatures shall be valid as part of the Constitution, namely:

Article XV.

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude—

Section 2. The Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

Schuyler Colfax

Speaker of the House of Representatives.

B.F. Wade

President of the Senate pro tempore.

Attent.ED McPherson

Clerk of House of Representatives.

Geo. C. Gorham

Secy of Senate U.S.

This primary source comes from the General Records of the United States Government.

National Archives Identifier: 299797

Full Citation: Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution; 2/26/1869; Enrolled Acts and Resolutions of Congress, 1789 - 2011; General Records of the United States Government, ; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/fifteenth-amendment, April 25, 2024]Joint Resolution Proposing the Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

Page 1