Executive Order 9066

The Great Depression and World War II (1929-1945)

A National Archives Foundation educational resource using primary sources from the National Archives

Published By:

Historical Era:

Thinking Skill:

Bloom’s Taxonomy:

Grade Level:

Use this activity while teaching about Japanese American internment or World War II, or in a unit on civil liberties or civics. Students can complete the activity individually, in small groups, or in pairs. For grades 10-12 through college/university (or upper middle school students with a solid background in historical document analysis). Approximate time needed is 60-90 minutes.

A note on terminology:

The historical primary source documents included in this activity reflect the terminology that the government used at the time, such as alien, evacuation, relocation, relocation centers, and Japanese (as opposed to Japanese American). The activity also uses the terms of forced relocation, forced removal, internment, incarceration, and Japanese American. (See more about terminology from the Densho website.)

Before beginning the activity, ask students to collaboratively define the term civil liberties and brainstorm some examples. You can share with students the following definition, which is also presented during the activity:

Civil liberties are basic or natural rights and freedoms that people have, or protections from government interference or against unjust government actions.

Explain to students that they will be learning about the violation of the civil liberties of Japanese Americans during World War II. Ask them to open and begin the activity by reading through the introduction and instructions. They will then read and analyze a series of primary source documents and photographs, while responding to prompts throughout to guide them in their understanding of the “relocation” of Japanese Americans.

Possible student responses to the activity questions might include:

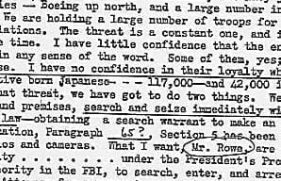

What clues did you find as to why the government specifically targeted Japanese Americans? Did anyone disagree with these reasons?

What civil liberties were Japanese Americans denied?

In the government report about the relocation program, what kind of language and wording is used? How do you think this would have been written differently if from the perspective of the people imprisoned in the camps?

Looking through the photos, list at least two examples of how they attempt to depict “normal life,” as well as at least two ways that they show civil liberties being denied.

Why did government officials think the program was necessary? How did they argue that it didn’t violate the Constitution?

After students have made their way through all of the primary sources and questions, they should click on “When You’re Done” and respond to additional information about actions that the government took in the 1980s to redress these past injustices:

Students will read an excerpt from the 1984 Korematsu decision and summarize the lesson that the court wanted Americans to learn from this history.

A historical note:

In addition to Japanese Americans, other groups of people had their civil liberties violated during World War II. After Japan attacked and occupied southeastern Alaska, the United States “relocated” 881 Aleut/Unangax̂ from the Aleutian and Pribilof Islands to four internment camps in Alaska. On their return, some Aleuts/Unangax̂ found their villages leveled, while others found their homes and property had been looted or destroyed by American troops. Additionally, hundreds of German and Italian nationals and U.S. citizens were excluded from the West Coast military zones; and over 14,000 people of German and Italian ancestry were incarcerated in Justice Department and Army camps around the country.

In this activity, students will analyze a variety of documents and photographs to learn how the government justified the forced relocation and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, and how civil liberties were denied.