In this short analysis activity, students will compare and contrast two images taken in Virginia public schools in 1948: one from a school open to White children only, and the other from a school for Black children. Students will explore these images to discuss the differences in public school accommodations in a segregated school district.

Suggested Teaching Instructions

This activity is intended as a warm-up or introduction to a unit related to school desegregation, the

Brown v.

Board of Education Supreme Court case, or civil rights in general. For grades 6-12. Approximate time needed is 20-30 minutes.

Present the activity to the entire class and prompt students to carefully examine the two photographs. You may choose to walk through the entire activity as a full class; or you can ask students to open the activity themselves on their devices. If they open it themselves, point out the arrows and magnifying glass icons on the photos that they can use to take a closer look. But ask them

not to click on "View Entire Document" during their initial analysis, which would reveal information about the image.

Model careful analysis with the first photograph (a bathroom stall at Gloucester High School, a school for Black students in Gloucester County, Virginia – do not reveal this information to students yet). Instruct students to the answer the analysis questions found beneath:

Meet the photo.

Quickly scan the photo. What do you notice first?

Observe its parts.

List the objects you see.

Write one sentence summarizing this photo.

Try to make sense of it.

Why do you think this photo was taken?

Next, click on the second photograph (bathroom stalls at Botetourt High School, a school for White students in the same county – again, do not reveal this information). Ask students to answer the same questions about this image.

Conduct a full-class discussion comparing and contrasting the photographs. Ask students what major differences are apparent and how these two images may be related to each other. If students hypothesize that they depict a White school versus a Black school, ask them to provide evidence that supports that view.

Click on "When You're Done" where students will learn that the photographs depict bathroom accommodations at two high schools in the same county in Virginia: 1) Botetourt High school for White students, and 2) Gloucester High School for Black students.

Continue the class discussion after giving students time to individually respond to the following:

- What do these two photos tell you about the equality of educational facilities provided to White and Black students in Gloucester County, Virginia?

You can provide the following additional information:

These photographs come from the court case

Alice Lorraine Ashley v. School Board of Gloucester County. It was one of several cases that lawyers from the Virginia chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) brought to U.S. District Courts across Virginia to attempt to equalize educational opportunities for Black and White students. (Almost all of Virginia's population at the time was recorded as either White or Black. According to Virginia's "racial integrity laws," enacted in 1924-1930, Whites were those with "no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian"; and all non-White students, including the small population of American Indians, were categorized as "colored" or Black.)

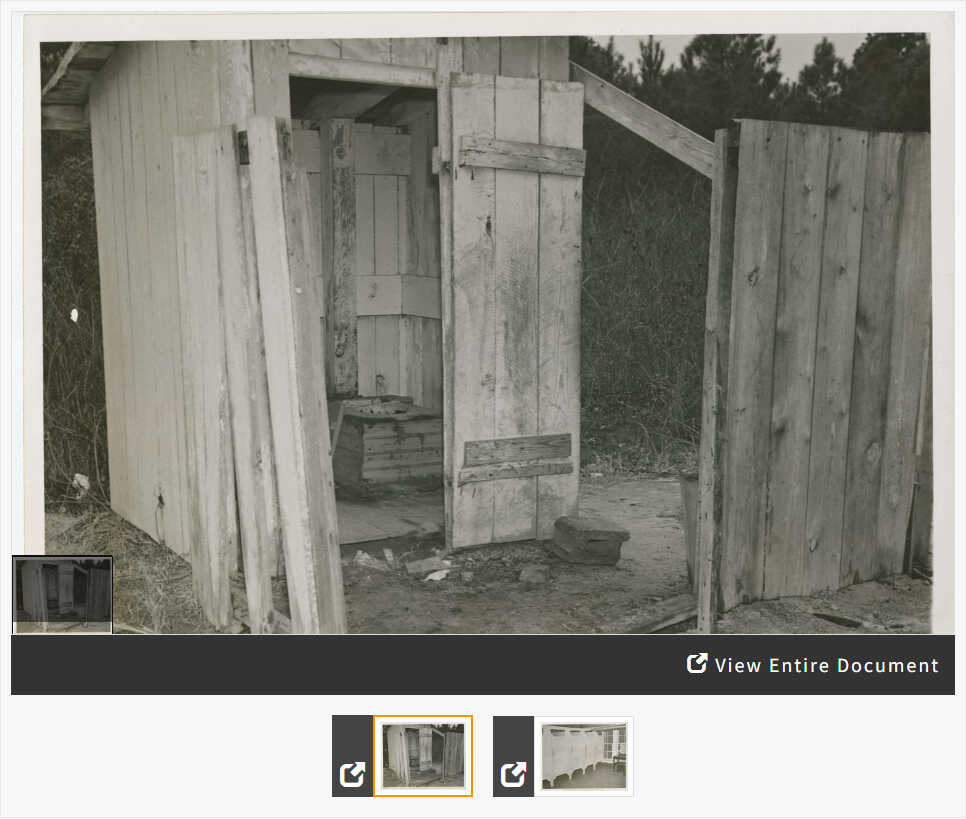

The plaintiffs entered these photograph as evidence in the case to show the unequal facilities at schools for White and Black students in Gloucester County, Virginia. The first image, submitted by the plaintiffs as Exhibit No. 42, shows the boys bathroom stall at the Gloucester Training High School (the school for Black students), which was a single stall located outside with no running water. The second photograph, submitted by the plaintiffs as Exhibit No. 28, shows a girls bathroom at Botetourt High School (the school for White students) with at least five private indoor stalls, a small vanity mirror, and running water.

Botetourt had central heating, central plumbing, and smaller class sizes. Gloucester Training School had outdoor bathrooms, no central heat, and overcrowded classrooms. The school district spent significantly more money in the White school than they did in the Black school. The average annual cost per student at Botetourt was $81.63, versus $51.49 at Gloucester Training High School.

Judge Charles Sterling Hutcheson, U.S. District Court Judge for the Eastern District of Virginia, ruled that the school district was discriminating against Black students and teachers and that school officials needed to equalize the schools. But he emphasized that the court would not be enforcing the ruling, so these schools continued to remain separate and unequal.

Cases like

Alice Lorraine Ashley v.

School Board of Gloucester County contributed to the NAACP’s larger national campaign – the "equalization strategy" – which aimed to erode White support for segregated schools by demonstrating the financial cost of funding separate-but-equal schools for both Black and White students.

Judge Hutcheson’s ruling demonstrated the shortcomings of the NAACP’s equalization strategy. He recognized that the school district was discriminating against Black students and teachers, but offered no solution or path forward to equity. He articulated the NAACP’s thesis that fulfilling the "separate but equal" doctrine would make it too costly for school districts to maintain separate and equal facilities, but the toothless ruling left it up to the school district to decide how to equalize.

After 1950, the NAACP abandoned the equalization strategy and filed lawsuits directly challenging the constitutionality of the "separate but equal" doctrine. One such case was

Dorothy E. Davis, et al. v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, one of the five cases combined into

Brown v.

Board of Education that ruled segregation in schools unconstitutional in 1954.