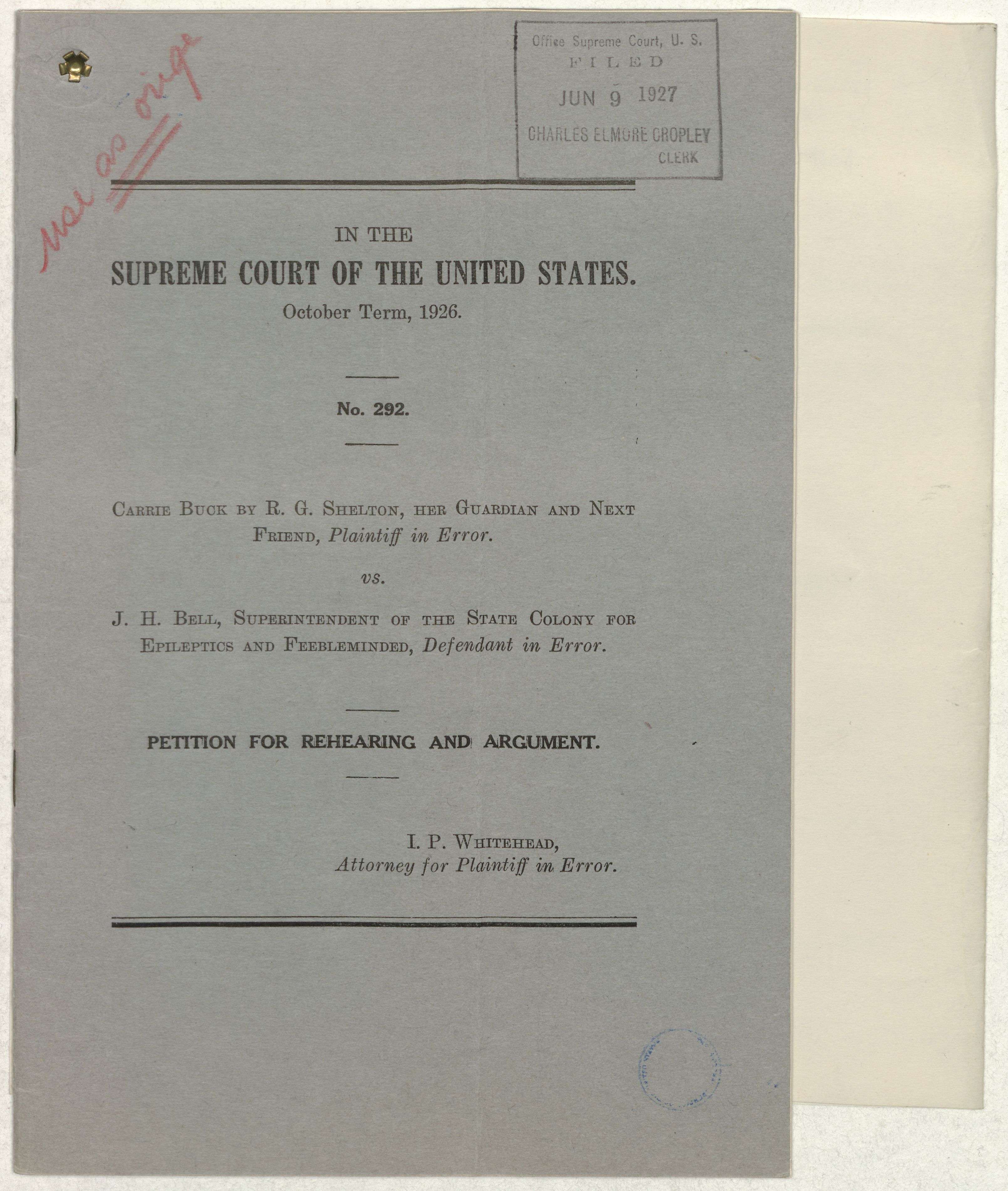

Petition for Rehearing and Argument to the Supreme Court from the case Buck v. Bell

6/9/1927

Add to Favorites:

Add all page(s) of this document to activity:

Add only page 1 to activity:

Add only page 2 to activity:

Add only page 3 to activity:

Add only page 4 to activity:

Add only page 5 to activity:

Add only page 6 to activity:

Add only page 7 to activity:

This document comes from the case file for Buck v. Bell, concerning the issue of involuntary sterilization. Following the U.S. Supreme Court's opinion from Justice Holmes, the lawyer for Carrie Buck filed this petition for a rehearing and argument based on constitutional grounds and disputing the analysis of court cases that were cited as precedence in the opinion.

At 17 years old, Carrie Buck became pregnant as a result of being raped. Shortly after her attack, her foster parents had her committed to the “Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded” on the grounds of feeble-mindedness, incorrigible behavior and promiscuity. Buck was declared mentally incompetent and her daughter was taken away from her.

Albert S. Priddy, the superintendent of the “Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded,” used Carrie to test the legality of Virginia’s involuntary sterilization law. John H. Bell replaced Priddy after his death in 1925.

On May 2, 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the state’s statute allowing for the sterilization of people who were thought of as “unfit,” including the intellectually disabled. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. delivered the majority opinion of the Court, including: “It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind….Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” (This referenced the fact that Buck’s mother had been committed to a state institution, Buck’s diagnosis, and the assumption in the Court’s opinion that Buck’s children would be “socially inadequate.”)

Bell performed Buck’s sterilization on October 19, 1927. She was the first person involuntarily sterilized under Virginia’s Laws for the sterilization of persons considered “unfit” — an estimated 8,300 Virginians were sterilized under the state law from 1927 to 1972.

At 17 years old, Carrie Buck became pregnant as a result of being raped. Shortly after her attack, her foster parents had her committed to the “Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded” on the grounds of feeble-mindedness, incorrigible behavior and promiscuity. Buck was declared mentally incompetent and her daughter was taken away from her.

Albert S. Priddy, the superintendent of the “Colony for Epileptics and Feeble-Minded,” used Carrie to test the legality of Virginia’s involuntary sterilization law. John H. Bell replaced Priddy after his death in 1925.

On May 2, 1927, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the state’s statute allowing for the sterilization of people who were thought of as “unfit,” including the intellectually disabled. Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. delivered the majority opinion of the Court, including: “It is better for all the world if, instead of waiting to execute degenerate offspring for crime or to let them starve for their imbecility, society can prevent those who are manifestly unfit from continuing their kind….Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” (This referenced the fact that Buck’s mother had been committed to a state institution, Buck’s diagnosis, and the assumption in the Court’s opinion that Buck’s children would be “socially inadequate.”)

Bell performed Buck’s sterilization on October 19, 1927. She was the first person involuntarily sterilized under Virginia’s Laws for the sterilization of persons considered “unfit” — an estimated 8,300 Virginians were sterilized under the state law from 1927 to 1972.

Transcript

[red pencil] use as orig[stamp] Office Supreme Court, U.S. FILED JUN 9 1927 CHARLES ELMORE CROPLEY, CLERK

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE UNTED STATES.

October Term, 1926.

No. 292.

CARRIE BUCK BY R.G. SHELTON, HER GUARDIAN AND NEXT FRIEND, Plaintiff in Error.

vs.

J.H. BELL, SUPERINTENDENT OF THE STATE COLONY FOR EPILEPTICS AND FEEBLEMINDED, Defendant in Error.

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND ARGUMENT.

I.P. WHITEHEAD, Attorney for Plaintiff in Error.

[blue circle stamp]

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

October Term, 1926.

No. 292.

CARRIE BUCK BY R. G. SHELTON, HER GUARDIAN AND NEXT

FRIEND, Plaintiff in Error.

vs.

J. H. BELL, SUPERINTENDENT OF THE STATE COLONY FOR

EPILEPTICS AND FEEBLEMINDED, Defendant in Error.

PETITION FOR REHEARING AND ARGUMENT.

To the Honorable Chief Justice and the Associate Jus-

tices of the Supreme Court of the United States:

The plaintiff who brought this action in behalf of others similarly situated as well as in her own behalf, respectfully petitions the Court for a rehearing of this case upon the following grounds and for the reasons here show.

First: Upon the ground and for the reason that the Court appears to have held that a State has the power, in the absence of an emergency or of danger threatening the welfare of all, to deprive some of its citizens of the right to bodily integrity guaranteed to them by the Constitution of the United States, contrary to its former decisions interpreting applicable provisions of the Federal Constitution

and contrary to general principles of law and justice.

In this decision relied upon to support your holding in this case (Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U. S. 11) this Court

2

recognized and seems to have established that all citizens, the mentally and physically sick as well as those in possession of good health and normal faculties, are protected in the enjoyment of life and of those liberties which are guaranteed under the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments of the Constitution. This Court said in Jacobson v. Massachusetts on p. 29 that the citizen is safe in the enjoyment of his life and liberties but that "in every well ordered society charged with the duty of conserving the safety of its members, the rights of the individual in respect of his liberty may, at times, under pressure of great dangers be subject to such restraint to be enforced by reasonable regulations as the safety of the general public may demand."

In Railroad v. Husen, 95 U.S. 465, at p. 473, your Court declined to concur in the decisions of those State Courts which refused to inquire whether statutes enacted in the exercise of the police power for the protection of the public welfare, went beyond the danger to be apprehended. Some Courts had held that such an inquiry is for the legislature and not for the courts. Your Court, however, held in that case that "the police power of a state cannot go beyond the necessity for its exercise; and under cover of it objects not within its scope cannot be secured at the expense of the protection afforded by the Federal Constitution." You have thus held that the State has no power to deprive any of its citizens of rights enjoyed by all unless compelled to do so under pressure of great dangers in order to insure the safety of all.

It would seem, therefore, in the light of these decisions, that in the absence of real necessity for this statute, as for example, that in Virginia the number of defectives requiring care in state institutions had increased to such an extent that the cost of keeping them has grown beyond the power of the State to bear, with reasonable regard for its duty to its citizens, its enactment cannot be justified. The statute under consideration in this case does not declare

3

that a danger exists which threatens the welfare of the people of Virginia or that Virginia is unable to bear the burden of keeping and caring for its mentally defective citizens. Nor does the testimony upon which the finding of the lower Courts is based disclose such a condition. The Legislature, in the preamble of the Act, based the enactment of the statute upon arbitrary assumption, pretended authority and mere conjecture. The statute merely declares that the health of the individual patient and the welfare of society may be promoted in certain cases by the sterilization of mental defectives "under careful safeguard and by competent and conscious authority."

The statute, therefore, on its face is an arbitrary, wanton and spoliative act. It does not disclose any relation whatever to an existing or imminent danger threatening the welfare of the people of Virginia which, in the interest of public welfare, would justify the enactment of this law and require the sacrifice it exacts of the classes of citizens embraced within its terms. By its own declarations the statute would seem to deserve your condemnation unless you are prepared to depart from your former decisions and from well established traditions and policies of the country that it is the duty of all governments to care for and provide medical and scientific treatment for their mentally and physically sick and maintain them in public institutions when they become a public charge.

Second: For the reason that you appear in your decision in this case to have given your former decision in Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, an application far beyond the scope to which it was expressly limited by the Court. In that case the Court stated in the final paragraph, p. 39, that: "We now decide, and decide only that the statute covers the present case, and that nothing clearly appears that would justify this Court in holding it to be unconstitutional and inoperative in its application to the plaintiff in error."

6

other cases of similar import applicable to the questions raised, including Jacobson v. Massachusetts, 197 U.S. 11, at p. 28.

In the first of these cases, Allgeyer v. Louisiana, the Court defined the term "liberty" as used in the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution. It said:

"The liberty mentioned in the Amendment means not only the right of the citizen to be free from the mere physical restraint of his person, as by incarceration, but the term is deemed to embrace the right of the citizen to be free in the enjoyment of all his faculties, to be free to use them in all lawful ways."

This general definition of the term "liberty" would seem completely to comprehend the earlier definition of the term "life" given by Mr. Justice Field in the dissenting opinion in Munn v. Illinois, 94 U.S. 113, wherein he said:

"By the term life as here used, something more is meant than mere animal existence. The inhibition against its deprivation extends to all those limbs and faculties by which life is enjoyed. The provision equally prohibits the mutilation of the body by the amputation of a leg, or the putting out of an eye, or the destruction of any other organ of the body by which the soul communicates with the outer world. The deprivation not only of life, but of whatever God has given to every one with life for its growth and enjoyment, is prohibited by the provision in question, if its efficacy be not frittered away by judicial decision."

In Holden v. Hardy, 169 U.S. 366, this Court recognized that, to a certain extent, the law is a progressive science; that in some states methods of procedure which at the time the Constitution was adopted were deemed to be essential to the protection and safety of the people, or to the liberty of its citizens have been found to be no longer necessary;

7

but it held that the power of the State to impose restrictions upon the liberties of its citizens "is limited by the fundamental principles laid down in the Constitution, to which each member of the Union is bound to accede as a condition of its admission as a State."

The extent to which a State may curtail the liberties of its citizens or impose restrictions upon the exercise of the rights guaranteed to them by the Constitution were discussed by Mr. Justice Peckham, speaking for the Court in Lockner v. New York, 198 U.S. 45. Mr. Justice Sutherland, of the present Court, adopted as his own much of the language used by Mr. Justice Peckham and quotes him in Adkins v. Children's Hospital, 261 U.S. 525, at p. 546, as follows:

"It must, of course, be conceded that there is a limit to the valid exercise of the police power by a state. There is no dispute concerning the general proposition. Otherwise the Fourteenth Amendment would have no efficacy, the legislatures of the states would have unbounded power, and it would be enough to say that any piece of legislation was enacted to conserve morals, the health or safety of the people. Such legislation would be valid no matter how absolutely without foundation the claim might be. The claim of the police power would be a mere pretext--become another delusive name for the supreme sovereignty of the state to be exercised free from constitutional restraint...

"...It is a question which of two powers or rights shall prevail--the power of the State to legislate or the right of the individual to liberty of person and freedom of contract. The mere assertion that the subject relates, though but in remote degree, to the public health does not necessarily render the enactment valid. The act must have a more direct relation as a means to an end, and the end itself must be appropriate and legitimate before an act can be held to be valid which inter-

8

feres with the general right of an individual to be free in his person and in his power to contract in relation to his own labor...

"....It is also urged, pursuing the same line of argument, that it is to the interest of the State that its population should be strong and robust, and therefore any legislation which may be an aid to or tend to make people healthy must be valid as a health law, enacted under the police power. If this be a valid argument and justification for this kind of legislation, it follows that the protection of the Federal Constitution from undue interference with the liberty of person and freedom of contract is visionary, wherever the law is sought to be justified as a valid exercise of the police power. Scarcely any law but might find shelter under such assumptions and conduct, properly so called, as well as contract would come under the restrictive sway of the legislature."

Justice Sutherland in Adkins v. Children's Hospital, after adopting and approving the conclusions of Mr. Justice Peckham in the earlier case, concludes on p. 561:

"The liberty of the individual to do as he pleases even in innocent matter, is not absolute. It must frequently yield to the common good, and the line beyond which the power of interference may not be pressed is neither definite nor unalterable but may be made to move, within limits not well defined, with changing need and circumstances. Any attempt to fix a rigid boundary would be unwise as well as futile. But, nevertheless, there are limits to the power and when these have been passed, it becomes the plain duty of the Courts in the proper exercise of their authority to so declare. To sustain the individual freedom of action contemplated by the Constitution is not to strike down the common good but to exalt it; for surely the good of society as a whole cannot be better served than by the preservation against arbitrary restraint of the liberties of its constituent members."

[[next page]]

9

Coppage v. Kansas, 236 U.S. 1, involved the liberty to contract for personal services. The Court said, at p. 14:

"Included in the right of personal liberty and the right of private property--partaking of the nature of each--is the right to make contracts for the acquisition of property......If this right be struck down or arbitrarily interfered with, there is a substantial impairment of liberty in the long established constitutional sense.....An interference with this liberty so serious as that now under consideration and so disturbing of equality of right, must be deemed to be arbitrary unless it be supportable as a reasonable exercise of the police power of the State.

Page 15. "......When a party appeals to this Court for the protection of rights secured to him by the Federal Constitution the decision is not to depend upon the form of the State law, nor even upon its declared purpose, but rather upon its operation and effect as applied and enforced by the State; and upon these matter this Court cannot, in the performance of its duty, yield its judgment to that of the State Court.

Page 17. "......The Fourteenth Amendment in declaring that a State shall not 'deprive any person of life, liberty or property without due process of law' gives to each of these an equal sanction; it recognizes 'liberty' and 'property' as co-existent human rights, and debars the States from any unwarranted interference with either.

"And since a State law may not strike them down directly it is clear that it may not do so indirectly, as by declaring in effect that the public good requires the removal of those inequalities that are but the normal and inevitable result of their exercise, and the invoking of the police power in order to remove the inequalities without other object in view. The police power is broad and not easily defined, but it cannot be

10

given the wide scope that is here asserted for it without in effect nullifying the constitutional guaranty."

It would seem, therefore, that the decision which you have just rendered in this case is wholly out of accord with previous decisions of this Court in cases involving similar principles and the petition for rehearing is justified and ought to be granted on this ground alone.

Fourth: Having pointed out that the statute is based upon the speculative conclusion stated in its preamble that the welfare of society may be promoted in certain cases by the sterilization of persons suffering from inheritable feeblemindedness, imbecility, idiocy or insanity, and that the health of the individual patient may be aided by such treatment, the Court is also asked to review its decision in this case in the light of its decision in Truax v. Corrigan, 257 U.S. 312, and consider the statute as a classification based upon legalized experiment in sociology.

This case is the first involving human sterilization to reach this Court for decision. The record admits that sterilization of feebleminded, imbeciles and insane persons is not generally practised. It is a matter of common knowledge that it is not and likewise common knowledge that the beneficent effects of sterilization upon the public welfare claimed by its advocates not only are not generally admitted, but are denied by competent medical and sociological authority all over the country.

The Act, by its very nature is therefore based upon speculative grounds and is experimental. The case therefore comes within the application of syllabus 10 of Truax v. Corrigan, supra.

In that case the learned Chief Justice, Mr. Taft, said in syllabus 10:

"A classification cannot be upheld as a legalized experiment in sociology; the very purpose of the Con-

11

stitution was to prevent experimentation with the fundamental rights of the individual."

At page 338 the learned Chief Justice said further:

"Classification like the one with which we are here dealing is said to be the development of the philosophic thought of the world and is opening the door to legalized experiment. When fundamental rights are thus attempted to be taken away, however, we may well subject such experimet to attentive judgment. The Constitution was intended, its very purpose was, to prevent experiementation with the fundamental rights of the individual."

Fifth: Contrary to its declaration that it has been enacted to promote public welfare the statute in its operation will be detrimental to public morals, public health and public welfare.

The promotion of morality and of public health and safety, i.e., the public welfare, is one of the duties of the state and of the National Government. It is disclosed in the record that the persons affected by the statute under consideration have marked immoral and degenrate tendencies which they are prevented from indulging while in institutions provided for their care. The record likewise discloses that patients who may be sterilized under the provisions of the statute and returned to society are none the less immoral or cured of their immoral and degenerate tendencies after sterilization. If, therefore, sterilization is practised to an extent sufficient to make appreciably felt what are supposed to be beneficiant purposes of the Act, great evil instead of good would result. It would require that large numbers of men and women confined in the State institutions be treated and discharged in order to accomplish the purpose of the Act. These would become a menace to society, breeders of disease, offenders against the laws and a dangerous element requiring, perhaps, a larger

12

expenditure for their supervision and control than is now needed for their restraint.

We think, therefore, that without a more ample consideration and statement of what you regard as the gain to society and the welfare of the people as a whole than is contained in your decision, the conviction will remain that the people of Virginia will be more harmed than helped by the adoption and enforcement of this law. Moreover, your decision will be regarded as the signal for the breakdown of the present policy of the states to safeguard and promote morality, because such an act as the Virginia statute makes physical health and not moral intergrity the cornerstone of the State.

The foregoing is a brief statement of some of the reasons we would expect to advance upon rehearing to show error in your decision and some of the authorities upon which we would rely to support our claim that the statute under consideration is not a valid enactment.

We therefore more respectfully pray your Honorable Court to review its decisions in this case and upon rehearing to correct the errors complained of in this petition.

L.P. WHITEHEAD,

Attorney for Plaintiff in Error.

The undersigned, attorney of record for the petitioner, Carrie Buck, by R.G. Shelton, her guardian and next fiend, hereby certified that this petition for a reconsideration of this case is presented in good faith and not for delay.

L.P WHITEHEAD.

This primary source comes from the Records of the Supreme Court of the United States.

National Archives Identifier: 45637229

Full Citation: Petition for Rehearing and Argument to the Supreme Court from the case Buck v. Bell; 6/9/1927; Buck v. Bell (Case File #31681); Appellate Jurisdiction Case Files, 1792 - 2010; Records of the Supreme Court of the United States, Record Group 267; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/petition-rehearing-argument-to-supreme-court-buck-v-bell, April 19, 2024]Rights: Public Domain, Free of Known Copyright Restrictions. Learn more on our privacy and legal page.