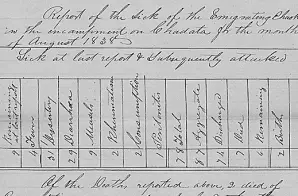

This document, written by a Dr. Edward, reports on the sickness and suffering endured by the Cherokee people during their forced removal, what is now known as the “Trail of Tears.”

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 was the first major step in forcibly relocating American Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River to land further west. Then in 1835, a small group of Cherokee leaders who favored moving west signed the Treaty of New Echota with representatives of the U.S. government. It required the eastern Cherokees to exchange their lands for land in the “Indian Territory”—what is today eastern Oklahoma.

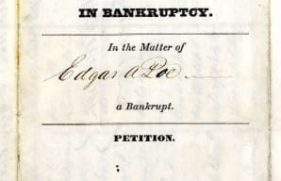

Principal Chief John Ross and the majority of the Cherokee people opposed the treaty, claiming it was invalid because the Principal Chief did not sign it and those who did were not authorized to create a treaty. All but about 2,000 Cherokees ignored the treaty and refused to move west or begin making preparations for removal. This reaction was encouraged by Chief Ross and continued for nearly two years.

Between 1835 and 1838, the small faction of Cherokees who had agreed to the treaty removed themselves to the west, either individually or in several Government-run detachments, in the first phase of Cherokee removal.

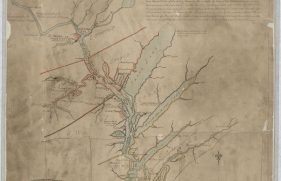

The next stage of removal, beginning what is known as the Trail of Tears, occurred when other Cherokees were rounded up by troops commanded by Gen. Winfield Scott in the spring of 1838 and forced into stockades and military stations throughout the Cherokee Nation. They were then forcibly moved to Indian Territory under military escort, using boat transportation via the Tennessee, Ohio, Mississippi, and Arkansas Rivers.

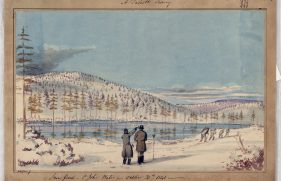

Despite Scott’s order calling for removal in a humane fashion, this did not happen. Some people had to walk as many as 1,000 miles over a four-month period. Approximately 4,000 of 16,000 Cherokee people died along the way. Chief John Ross petitioned General Scott to let the Cherokee control their own removal; and in the fall and winter of 1838–39, most remaining Cherokees migrated to Indian Territory under the leadership of Chief Ross.