President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Day of Infamy Speech

12/8/1941

Add to Favorites:

Add all page(s) of this document to activity:

Add only page 1 to activity:

Add only page 2 to activity:

Add only page 3 to activity:

President Franklin D. Roosevelt delivered this joint address to Congress on December 8, 1941, the day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. This is the official copy of FDR's speech presented to the Senate.

His famous “Day of Infamy” speech was a call to arms. He expressed outrage at Japan and confidence in the “inevitable triumph” of the United States. Roosevelt concluded by asking Congress to declare that a state of war existed between the United States and Japan. Immediately afterward, Congress declared war, and the United States entered World War II.

On December 7, 1941, the U.S. naval base on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, had been subject to an attack that was one of the greatest military surprises in the history of warfare. In less than two hours, the U.S. Pacific Fleet was devastated, and more than 3,500 Americans were killed or wounded. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor catapulted the United States into World War II.

The American people were outraged. Though diplomatic relations between the United States and Japan were deteriorating, they had not yet broken off at the time of the attack. Instantly, the incident united the American people in a massive mobilization for war and strengthened American resolve to guard against any future lapse of military alertness.

Early in the afternoon of December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his chief foreign policy aide, Harry Hopkins, were interrupted by a telephone call from Secretary of War Henry Stimson and told that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. At about 5 p.m., following meetings with his military advisers, the President calmly and decisively dictated to his secretary, Grace Tully, a request to Congress for a declaration of war. He had composed the speech in his head after deciding on a brief, uncomplicated appeal to the people of the United States rather than a thorough recitation of Japanese treachery, as Secretary of State Cordell Hull had urged.

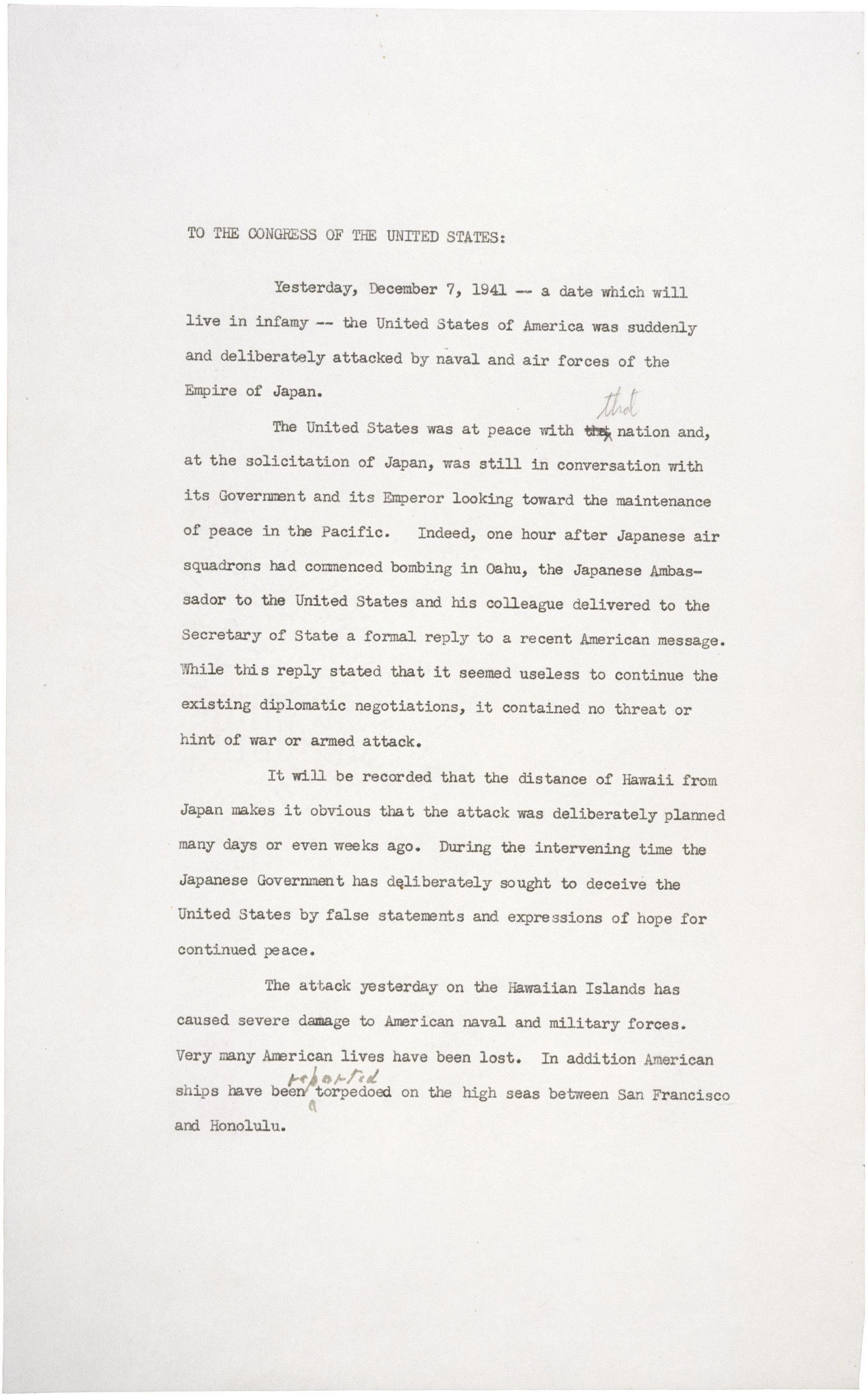

President Roosevelt then revised the typed draft—marking it up, updating military information, and selecting alternative wordings that strengthened the tone of the speech. He made the most significant change in the critical first line, which originally read, "a date which will live in world history." Grace Tully then prepared the final reading copy, which Roosevelt subsequently altered in three more places.

On December 8, at 12:30 p.m., Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress and the American people via radio. The Senate responded with a unanimous vote in support of war; only Montana pacifist Jeanette Rankin dissented in the House. At 4 p.m. that same afternoon, President Roosevelt signed the declaration of war.

His famous “Day of Infamy” speech was a call to arms. He expressed outrage at Japan and confidence in the “inevitable triumph” of the United States. Roosevelt concluded by asking Congress to declare that a state of war existed between the United States and Japan. Immediately afterward, Congress declared war, and the United States entered World War II.

On December 7, 1941, the U.S. naval base on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, had been subject to an attack that was one of the greatest military surprises in the history of warfare. In less than two hours, the U.S. Pacific Fleet was devastated, and more than 3,500 Americans were killed or wounded. The Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor catapulted the United States into World War II.

The American people were outraged. Though diplomatic relations between the United States and Japan were deteriorating, they had not yet broken off at the time of the attack. Instantly, the incident united the American people in a massive mobilization for war and strengthened American resolve to guard against any future lapse of military alertness.

Early in the afternoon of December 7, 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and his chief foreign policy aide, Harry Hopkins, were interrupted by a telephone call from Secretary of War Henry Stimson and told that the Japanese had attacked Pearl Harbor. At about 5 p.m., following meetings with his military advisers, the President calmly and decisively dictated to his secretary, Grace Tully, a request to Congress for a declaration of war. He had composed the speech in his head after deciding on a brief, uncomplicated appeal to the people of the United States rather than a thorough recitation of Japanese treachery, as Secretary of State Cordell Hull had urged.

President Roosevelt then revised the typed draft—marking it up, updating military information, and selecting alternative wordings that strengthened the tone of the speech. He made the most significant change in the critical first line, which originally read, "a date which will live in world history." Grace Tully then prepared the final reading copy, which Roosevelt subsequently altered in three more places.

On December 8, at 12:30 p.m., Roosevelt addressed a joint session of Congress and the American people via radio. The Senate responded with a unanimous vote in support of war; only Montana pacifist Jeanette Rankin dissented in the House. At 4 p.m. that same afternoon, President Roosevelt signed the declaration of war.

Transcript

TO THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES:Yesterday, December 7, 1941—a date which will live in infamy—the United States of America was suddenly and deliberately attacked by naval and air forces of the Empire of Japan.

The United States was at peace with that Nation and, at the solicitation of Japan, was still in conversation with its Government and its Emperor looking toward the maintenance of peace in the Pacific. Indeed, one hour after Japanese air squadrons had commenced bombing in the American Island of Oahu, the Japanese Ambassador to the United States and his colleague delivered to our Secretary of State a formal reply to a recent American message. And while this reply stated that it seemed useless to continue the existing diplomatic negotiations, it contained no threat or hint of war or of armed attack.

It will be recorded that the distance of Hawaii from Japan makes it obvious that the attack was deliberately planned many days or even weeks ago. During the intervening time the Japanese Government has deliberately sought to deceive the United States by false statements and expressions of hope for continued peace.

The attack yesterday on the Hawaiian Islands has caused severe damage to American naval and military forces. I regret to tell you that very many American lives have been lost. In addition American ships have been reported torpedoed on the high seas between San Francisco and Honolulu.

Yesterday the Japanese Government also launched an attack against Malaya.

Last night Japanese forces attacked Hong Kong.

Last night Japanese forces attacked Guam.

Last night Japanese forces attacked the Philippine Islands.

Last night the Japanese attacked Wake Island. And this morning the Japanese attacked Midway Island.

Japan has, therefore, undertaken a surprise offensive extending throughout the Pacific area. The facts of yesterday and today speak for themselves. The people of the United States have already formed their opinions and well understand the implications to the very life and safety of our Nation.

As Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy I have directed that all measures be taken for our defense.

But always will our whole Nation remember the character of the onslaught against us.

No matter how long it may take us to overcome this premeditated invasion, the American people in their righteous might will win through to absolute victory. I believe that I interpret the will of the Congress and of the people when I assert that we will not only defend ourselves to the uttermost but will make it very certain that this form of treachery shall never again endanger us.

Hostilities exist. There is no blinking at the fact that our people, our territory, and our interests are in grave danger.

With confidence in our armed forces—with the unbounding determination of our people—we will gain the inevitable triumph- so help us God.

I ask that the Congress declare that since the unprovoked and dastardly attack by Japan on Sunday, December 7, 1941, a state of war has existed between the United States and the Japanese Empire.

Franklin D. Roosevelt

The White House,

December 8, 1941

This primary source comes from the Records of the U.S. Senate.

National Archives Identifier: 595426

Full Citation: President Franklin D. Roosevelt's Day of Infamy Speech [Joint Address to Congress Leading to a Declaration of War Against Japan]; 12/8/1941; Messages, Reports, and Communications Tabled or Read, 1875 - 1968; Records of the U.S. Senate, Record Group 46; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/day-of-infamy-speech, April 27, 2024]Activities that use this document

- Two Versions of FDR's Infamy Speech

Created by the National Archives Education Team

Rights: Public Domain, Free of Known Copyright Restrictions. Learn more on our privacy and legal page.