In his annual message to Congress, President Andrew Jackson informed Congress on the progress of the removal of Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River to unsettled land in the west.

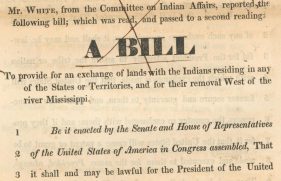

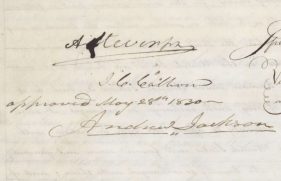

In the early 1800s, American demand for Indian nations’ land increased, and momentum grew to force American Indians further west. The first major step to relocate American Indians came when Congress passed, and President Andrew Jackson signed, the Indian Removal Act of May 28, 1830.

The Act authorized the President to negotiate removal treaties with Indian tribes living east of the Mississippi River, primarily in the states of Georgia, Tennessee, Alabama, Mississippi, North Carolina, and others. The goal was to remove all American Indians living in existing states and territories and send them to unsettled land in the west.

In his message on December 6, 1830, President Jackson informed Congress on the progress of the removal, stating, “It gives me pleasure to announce to Congress that the benevolent policy of the Government, steadily pursued for nearly thirty years, in relation to the removal of the Indians beyond the white settlements is approaching to a happy consummation.”

Jackson declared that removal would “incalculably strengthen the southwestern frontier.” Clearing Alabama and Mississippi of their Indian populations, he said, would “enable those states to advance rapidly in population, wealth, and power.”

By the end of Jackson’s Presidency, his administration had negotiated almost 70 removal treaties. These led to the relocation of nearly 50,000 eastern Indians to the Indian Territory—what later became eastern Oklahoma. It opened up 25 million acres of eastern land to white settlement and, since the bulk of the land was in the American south, to the expansion of slavery.

Perhaps the most well-known treaty, the Treaty of New Echota, ratified in 1836, called for the removal of the Cherokees living in Georgia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Alabama. The treaty was opposed by many members of the Cherokee Nation; and when they refused to leave, Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott was ordered to push them out. He was given 3,000 troops and the authority to raise additional state militia and volunteer troops to force removal.

Despite Scott’s order calling for the removal of Indians in a humane fashion, this did not happen. During the fall and winter of 1838-39, the Cherokees were forcibly moved from their homes to the Indian Territory—some having to walk as many as 1,000 miles over a four-month period. Approximately 4,000 of 16,000 Cherokees died along the way. This sad chapter in our history is known as the “Trail of Tears.”

By the 1840s, nearly all Indian tribes had been driven west, which is exactly what the Indian Removal Act intended to accomplish.

Andrew Jackson’s Message “On Indian Removal” is a part of America’s 100 Docs, an initiative of the National Archives Foundation in partnership with More Perfect that invites the American public to vote on 100 notable documents from the holdings of the National Archives. Visit 100docs.vote today.